December 2022

December 26, 2022

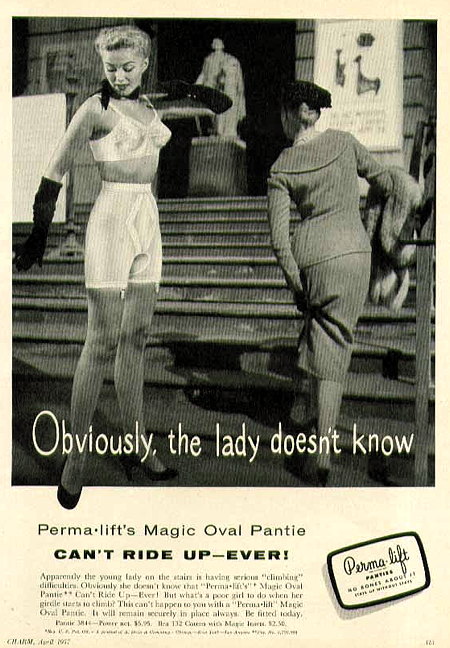

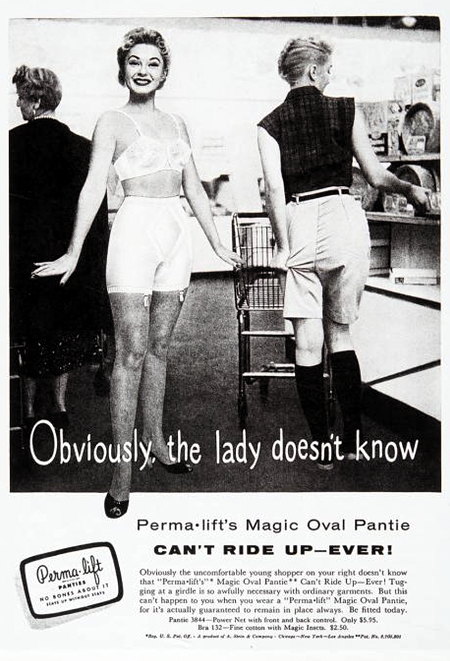

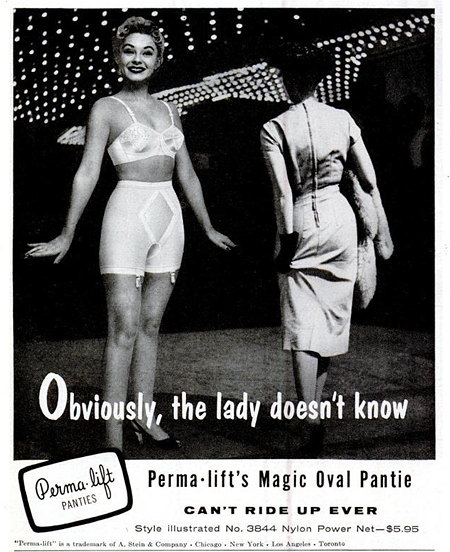

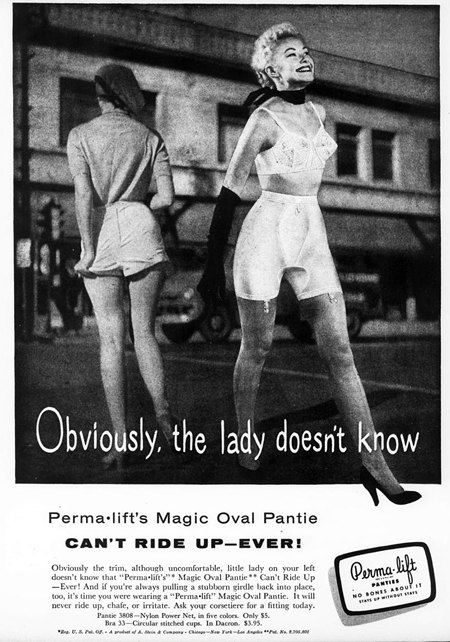

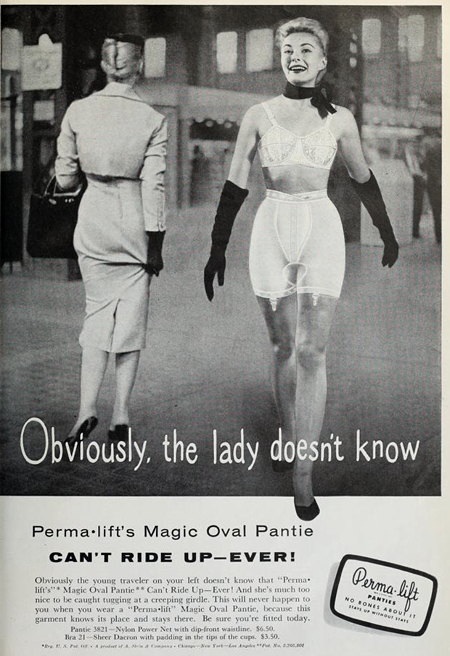

Magic Oval Panties

The Magic Oval Pantie lady had no qualms about parading around in public in her underwear and evening gloves, while her alter ego frantically tried to save herself from a wedgie.

Charm - Apr 1957

Posted By: Alex - Mon Dec 26, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Advertising, Underwear, 1950s

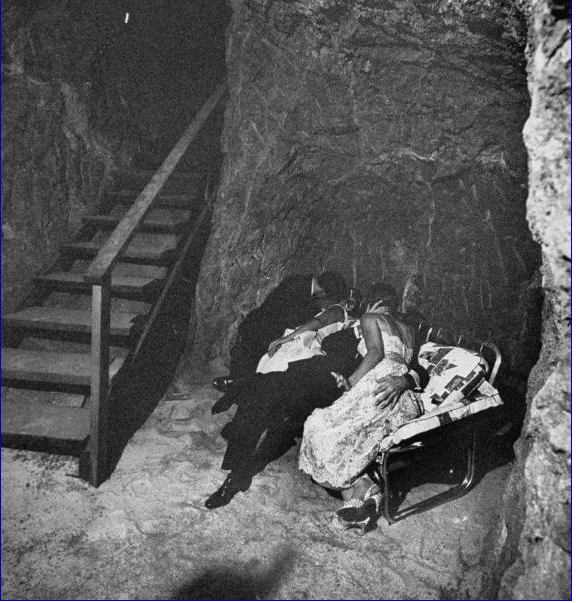

Hal Hayes’s Swinging Bachelor Mansion

For $600,000 -- adjusted for inflation, about $4.9 million today -- Hayes got a six-level, steel-and-glass pad with masculine, maximum technology and minimal custom decoration. He parked on girders projecting from the edge of his hillside lot, piped in hi-fi music, poured drinks from an ultra-sleek mini kitchen designed for catering, not for cooking, seduced brunettes in an orchid greenhouse and did what bachelors do in a free-standing “playroom.”

There was a circular fireplace, a louvered skylight, a mirrored master suite and an artificial beach for topless tanning. An outdoor hearth in gunite lava rock warmed women chilled by gin martinis.

Guests in the bomb shelter of Hal Hayes's house.

Retrospective write-up at the LA TIMES.

1958 feature in LIFE magazine.

Some great pix with this article.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Dec 26, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Architecture, Domestic, Excess, Overkill, Hyperbole and Too Much Is Not Enough, Space-age Bachelor Pad & Exotic, 1950s

December 25, 2022

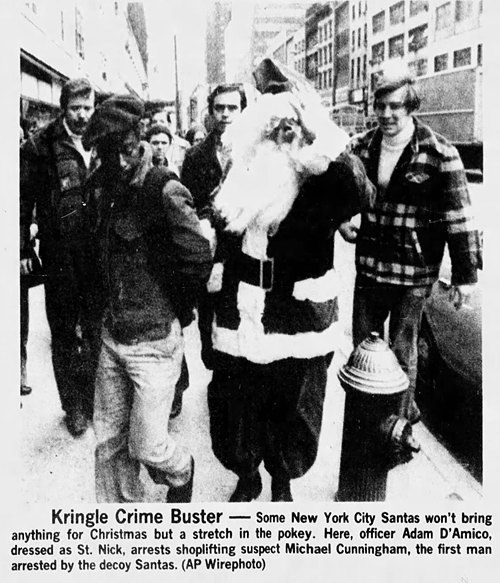

Decoy Santas

Arizona Daily Star - Dec 10, 1976

Posted By: Alex - Sun Dec 25, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Crime, Police and Other Law Enforcement, 1970s, Christmas

Merry Christmas 2022!

Posted By: Paul - Sun Dec 25, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Holidays, Headgear

December 24, 2022

Motorway Snooker

In his book Bobby on the Beat, former London policeman Bob Dixon described the game of motorway (or traffic) snooker:Over the years some drivers have filed complaints, claiming to have been victims of motorway snooker.

Sydney Morning Herald - Sep 11, 1999

Of course, the official position of the British traffic police is that their officers would not engage in such frivolous games. But that even if they did, all the cars they stopped were speeding anyway.

The Herts and Essex Observer - Jan 16, 1992

More info: BBC News

Posted By: Alex - Sat Dec 24, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Games, Police and Other Law Enforcement, Cars

Captain Entropy

The creator's Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Dec 24, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Drugs, Education, Music, Science, Children, Bohemians, Beatniks, Hippies and Slackers, 1970s

December 23, 2022

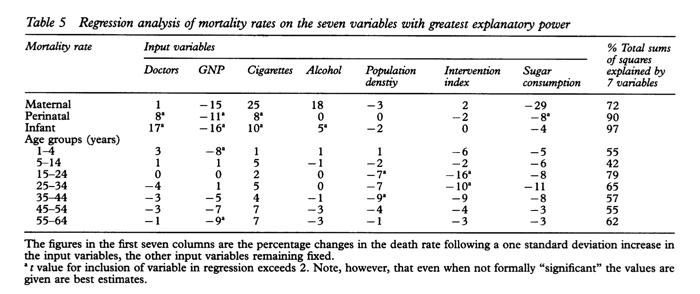

The Anomaly That Wouldn’t Go Away

In medical literature, the "anomaly that wouldn't go away" refers to a finding published in 1978 by a group of Welsh doctors (Cochrane, St Leger, and Moore). They had set out to examine the relationship between health services and mortality in the major developed countries, but in doing so they came across a correlation that surprised them — the more doctors there were per capita, the higher was the rate of infant mortality.The correlation wasn't a weak one. In fact, for infant mortality it was the strongest correlation in their study. The number of doctors per capita seemed to have a stronger negative impact on infant mortality than did the level of cigarette or alcohol consumption in the population.

Obviously the researchers found the correlation unsettling since, ideally, more doctors should result in fewer, not more, infants dying.

So why would more doctors correlate with higher infant mortality? The three doctors did their best to figure this out:

As the above passage indicates, they didn't think it was plausible that doctors themselves were somehow responsible for the elevated infant mortality, but nor could they come up with a satisfactory explanation for the correlation. So they called it "the anomaly that wouldn't go away."

I'm not sure if the correlation still holds true. I believe it still did about twenty years ago. Unfortunately much of the relevant literature is locked behind paywalls.

Over the years there have been quite a few attempts to explain the anomaly. I've listed two below. Again, I'm not sure if one has been accepted as THE explanation. So the anomaly may still persist.

It occurred to us that some of the countries richly endowed with physicians may obtain their large supplies by having bigger medical schools, larger classes, and thus less individual instruction of the medical student. The consequence could be a poorer standard of medical practice, the influence of which would be evident in the mortality of the younger age groups where the outcome of disease is most susceptible to the physician's skill.

The explanation proposed here is that, as compared with other regions, the expectation of opportunities in the growing industrial cities initially attracts an over supply of doctors. Once in practice, doctors in new regions enjoy fewer economies of scale, which means that they are more numerous as compared with the mature regions. These same industrialising cities attract rural immigrants whose health habits and supports break down in the context of city life. Thus, the places with the most doctors also have the highest death rates, but the two variables are associated only by common location.

More info (pdf): Cochrane, Leger, & Moore, "Health service 'input' and mortality 'output' in developed countries."

Posted By: Alex - Fri Dec 23, 2022 -

Comments (9)

Category: Babies, Death, Medicine

Hasbro’s Screwball

An early instance of "revenge of the nerds."

Posted By: Paul - Fri Dec 23, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Geeks, Nerds and Pointdexters, Sports, Toys, Advertising, 1970s, Puzzles

December 22, 2022

The 3M Force-Field

Invisible force-fields are the stuff of science fiction. However, there's an unusual case in which what seemed to be a force-field (or rather, an "invisible electrostatic wall") was created by accident at a 3M plant in the summer of 1980. The details of this force-field were later described by a 3M engineer in the 1997 Conference Proceedings of the Society of Plastics Engineers.More info: amasci.com

Posted By: Alex - Thu Dec 22, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Unlikely, Improbable and Counterfactual Phenomena

Monsters Under the Bed

It's highly gratifying to see an ancient cliche--OLD MAID CHECKS UNDER HER BED FOR MEN EVERY NIGHT--actually bearing fruit. Although not literally an "old maid," this wife's habit of looking under her bed for intruders paid off.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Dec 22, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Domestic, Sexuality, Stupid Criminals, Wives, 1910s

| Get WU Posts by Email | |

|---|---|

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction books such as Elephants on Acid. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Chuck Shepherd Chuck is the purveyor of News of the Weird, the syndicated column which for decades has set the gold-standard for reporting on oddities and the bizarre. Our banner was drawn by the legendary underground cartoonist Rick Altergott. Contact Us |