1930s

Follies of the Madmen #509

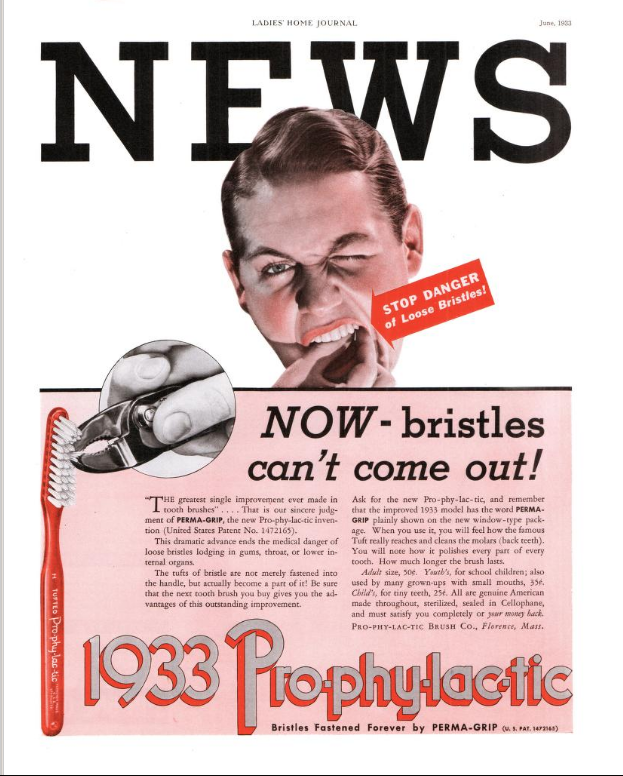

Was this ever such a drastic problem, or one of those made-up Madison Avenue problems?

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jun 15, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Business, Advertising, Hygiene, 1930s, Teeth

The 1964 Amphicar

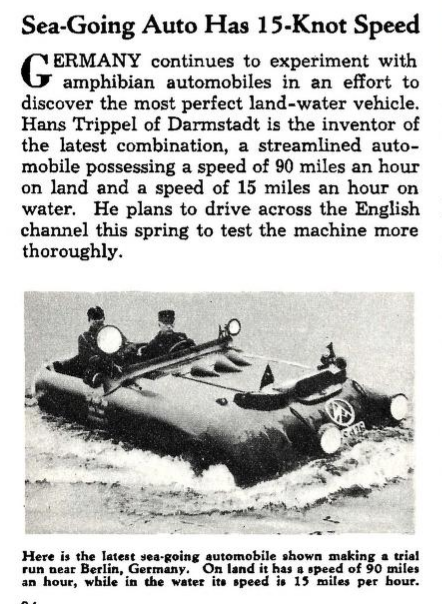

We've featured various amphibious vehicles on WU before. But my research seems to indicate we have not highlighted the most famous, seen in this video. Please note that inventor Hans Trippel was working on this concept thirty years previously, as seen in the clipping.

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Jun 13, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Inventions, Oceans and Maritime Pursuits, 1930s, 1960s, Cars

The Safety Smoker

The "safety smoker," invented by Glen R. Foote of Cincinnati, promised to allow people to safely smoke "in places where the danger from flying or falling sparks is likely to start a conflagration or cause an explosion."Perfect for anyone hankering for a smoke in an oil refinery.

San Francisco Examiner - Jan 1, 1933

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jun 07, 2021 -

Comments (6)

Category: Inventions, Smoking and Tobacco, 1930s

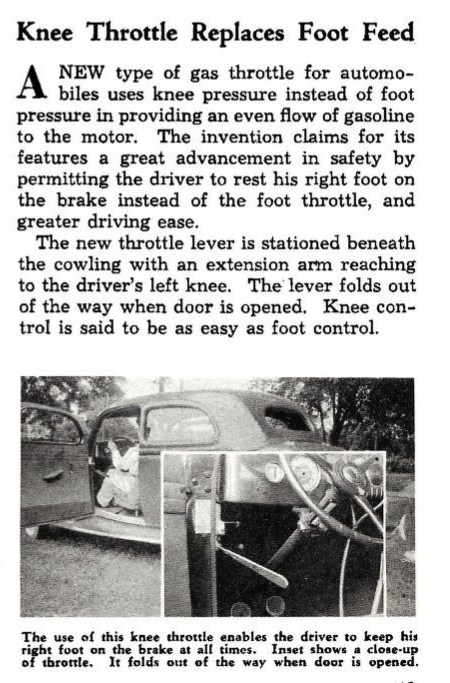

Alternate Accelerator

Is one's knee action as forceful, subtle and easy to control as foot action?

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jun 03, 2021 -

Comments (5)

Category: Death, Inventions, 1930s, Cars

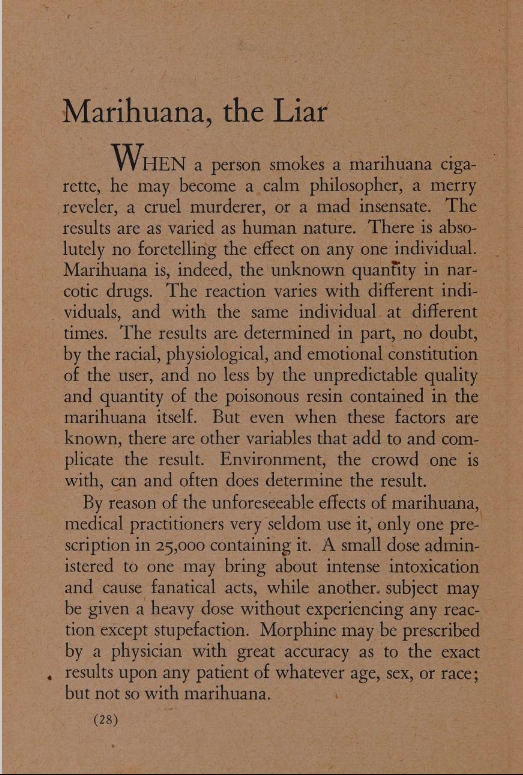

On the Trail of Marihuana

Read the whole thing here.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jun 01, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Drugs, Propaganda, Thought Control and Brainwashing, Juvenile Delinquency, 1930s

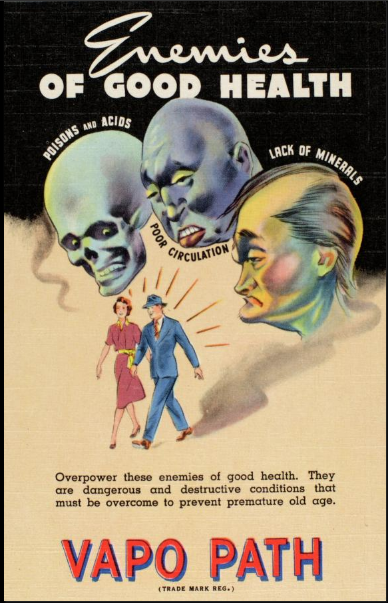

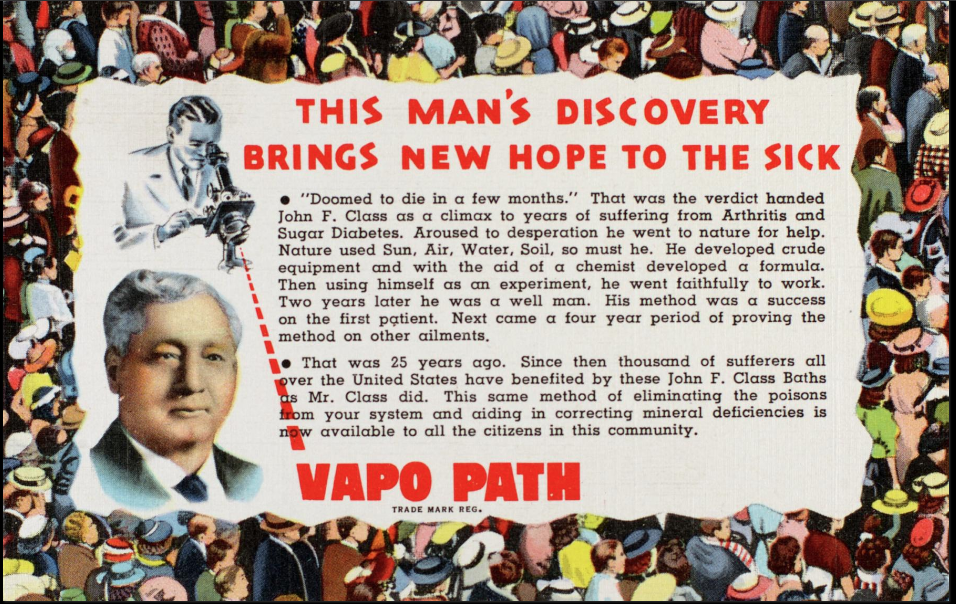

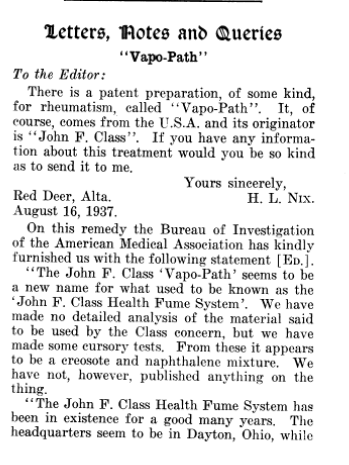

Vapo Path

Creosote and naphthalene! My favorite medicines!

Posted By: Paul - Fri May 21, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1930s, 1940s

The Golden Gate Bridge Bolt

In 1937, the city of San Francisco was busy preparing for the upcoming 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition when it was was approached by an engineer from Connecticut, Joseph Bazzeghin, who had an unusual proposal. He wanted to use the recently completed Golden Gate Bridge as a structure upon which to build the ultimate roller coaster, which he would call the Golden Gate Bridge Bolt. He envisioned this coaster being the centerpiece of the exposition, in the same way that the Eiffel Tower was the centerpiece of the 1900 Paris Exposition.

Image source: CA State Archives Newsletter

His plan involved attaching tracks to the cables of the bridge. These tracks would rise 300 feet above the first tower, and then drop 750 feet to the deck level of the center span — during which plunge the coaster would reach a speed of 190 mph. But then it would rise up again, 300 feet over the second tower, only to plunge 1000 feet toward the water and speed through a viaduct into Marin County.

During the second plunge riders would reach 220 mph, at which speed the force of the wind would make it impossible for them to breathe. So Bazzeghin planned to provide them with paper masks to protect their eyes, nose, and mouth.

His scheme was rejected, partially because the city was worried about drivers on the bridge being distracted by the sight of the roller coaster. But also because it would have been incredibly expensive, and possibly impossible, to build.

More info: CBS SF BayArea, SF Chronicle

Posted By: Alex - Tue May 18, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Architecture, Fairs, Amusement Parks, and Resorts, 1930s

Dr. Munch’s Marijuana Madness

1938: Dr. James Clyde Munch described to his students at Temple University what happened when he smoked "a handful of reefers" as an experiment.I'm thinking there may have been something more than just marijuana in those cigarettes.

Time - Apr 11, 1938

Munch liked his story about the disorienting effects of marijuana so much that he repeated it at several criminal trials.

New York Daily News - Apr 8, 1938

Posted By: Alex - Fri May 14, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Drugs, Smoking and Tobacco, Experiments, 1930s

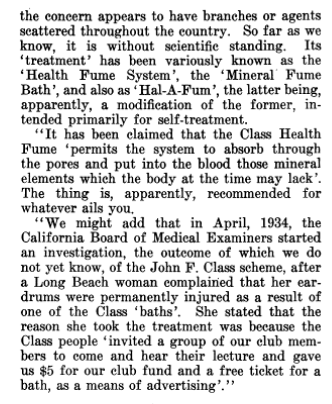

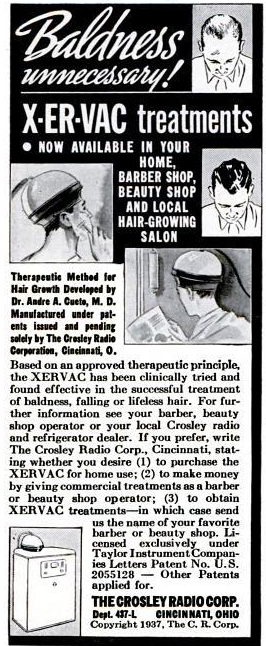

The Xervac Anti-Baldness Device

Read all about it here.

And here, source of the photo below.

Posted By: Paul - Tue May 11, 2021 -

Comments (8)

Category: Technology, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1930s, Hair and Hairstyling

Work continues during gas attack

"So business will not be interrupted if enemy airplanes should loose gas bombs on Rome before quitting time, a new transparent gas mask that enables a typist to see clearly while enjoying protection from noxious fumes has been introduced into the war-minded Italian capital."

Elmira Star-Gazette - Feb 4, 1935

Posted By: Alex - Sat May 01, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: War, 1930s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |