1930s

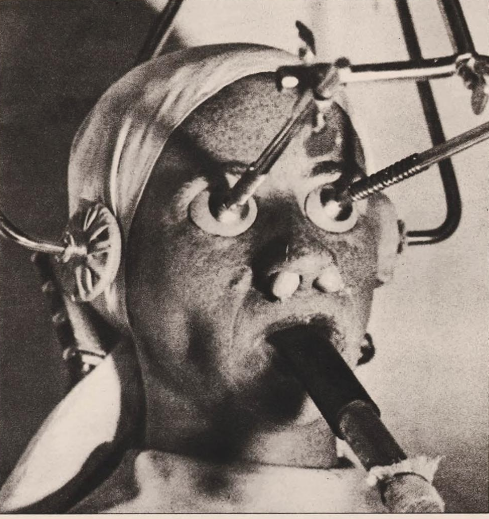

Mystery Gadget 85

What's happening to this poor woman?Answer is here.

Or behind the jump.

More in extended >>

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jul 06, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Technology, 1930s

Tony Galento’s Training Regimen

Wikipedia tells us:Galento, who claimed to be 5'9 (177 cm) tall, liked to weigh in at about 235 lb (107 kg) for his matches. He achieved this level of fitness by eating whatever, whenever he wanted. A typical meal for Galento consisted of six chickens, a side of spaghetti, all washed down with a half gallon of red wine, or beer, or both at one sitting. When he did go to training camp, he foiled his trainer's attempts to modify his diet, and terrorized his sparring partners by eating their meals in addition to his.

He was reputed to train on beer, and allegedly ate 52 hot dogs on a bet before facing heavyweight Arthur DeKuh. Galento was supposedly so bloated before the fight that the waist line of his trunks had to be slit for him to fit into them. Galento claimed that he was sluggish from the effects of eating all those hot dogs, and that he could not move for three rounds. Nevertheless, Galento knocked out the 6'3" (192 cm) DeKuh with one punch, a left hook, in the fourth round.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jun 30, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Excess, Overkill, Hyperbole and Too Much Is Not Enough, Food, Hygiene, Sports, 1930s

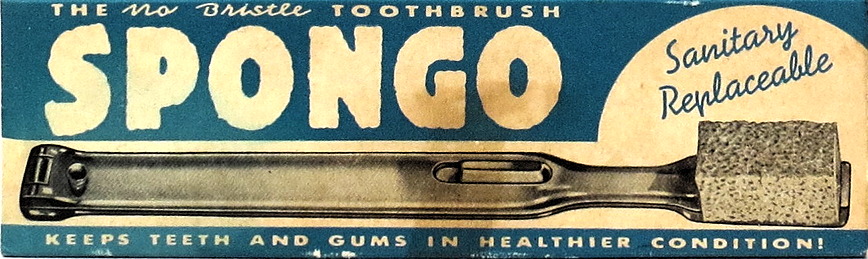

Spongo

"GET ACTUAL THRILL SENSATION USING SPONGO"

image source: Smithsonian

Wilkes-Barre Times Leader - May 25, 1938

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jun 01, 2020 -

Comments (6)

Category: Hygiene, 1930s, Teeth

Mystery Gadget 84

What does this machine do? Hint: it looks enormously overdesigned for its simple function.

The answer is here.

Or after the jump.

More in extended >>

Posted By: Paul - Mon May 18, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Technology, 1930s

Travel sack for dogs

Jalopnik draws attention to a similar, but sturdier-looking "bird's dog palace," also supported by a running board.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Apr 30, 2020 -

Comments (10)

Category: Dogs, 1930s, Cars

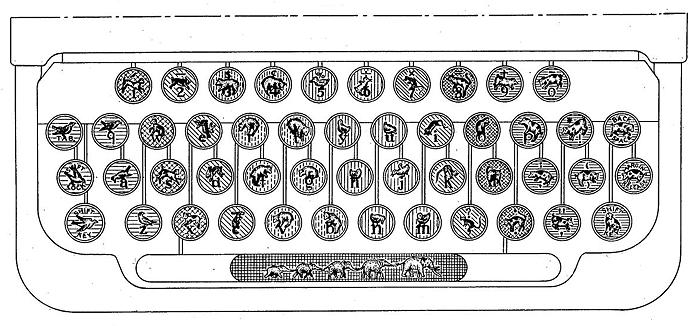

Animal Keyboard

The "animal keyboard," introduced by Smith Corona in the mid-1930s, was designed to teach children how to type by having pictures of animals on the keys of the typewriter. As explained by Merritt Ierley in his book Wondrous Contrivances:

The Antikey Chop website provides even more info about the animal keyboard, but I must be missing the point because I don't understand how having pictures of animals on the keys would make it any easier to learn how to type.

Allentown Morning Call - Jan 7, 1937

Posted By: Alex - Mon Apr 06, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Inventions, 1930s

Do Beavers Rule on Mars?

In the May 1930 issue of Popular Science magazine, Thomas Elway advanced the unusual hypothesis that Mars was inhabited by a race of beavers. His idea was subsequently reported in many newspapers.As far as I can tell, Elway wasn't actually a scientist. He was a journalist. So perhaps one shouldn't attach too much weight to his opinion. Still, he gets points for creativity.

Semi-Weekly Spokesman Review - Oct 12, 1930

Elway's argument was based on the assumption (widespread at the time) that there was plant life on Mars. Therefore, animal life was also considered possible. His reasoning then proceeded as follows:

This lack of manlike life is precisely what a biologist would expect. Man and man's active mind are believed to be products of the Great Ice Age, for that time of stress and competition on earth is what is supposed to have turned mankind's anthropoid ancestors into men. The period of ice and cold over wide areas of the earth was caused, at least in part, by the elevation of continents and mountain ranges. On Mars, no mountain ranges exist, and it probably never had an Ice Age.

It is on these hypotheses that science bases its assumption that there is no human intelligence on Mars, and that animal life on the planet is still in the age of instinct. The thing to expect on Mars, then, is a fish life much like that on earth, the emergence of this fish life onto the land, and the evolution of these Martian land-fishes into retilelike creatures. Finally, animals resembling the earth's present rodents like rats, squirrels, and beavers would make their appearance.

The chief reason to expect this final change of Martian retiles into primitive mammals lies in the fact that on earth this evolution seems to have been forced by changeable weather. And Mars now possesses seasonal changes like those on earth.

Pure biological reasoning makes it probable, therefore, that the evolution of warm-blooded animals may have occurred on Mars much as it did here. There seems no reason to believe that Martian life has gone farther than that. Mars is a relatively changeless planet. Biologists suppose that the rise and fall of mountains, the increase and decrease in volcanic activity, and the ebb and flow of climate forced life on earth along its upward path. Martian life of recent ages seems to have lacked these natural incentives to better things.

Now, there is one creature on earth for the development of whose counterpart the supposed Martian conditions would be ideal. That animal is the beaver. It is either land-living or water-living. It has a fur coat to protect it from the 100 degrees below zero of the Martian night.

The Martian beavers, of course, would not be exactly like those on earth. That they would be furred and water-loving is probable. Their eyes might be larger than those of the earthly beaver because the sunlight is not so strong, and their bodies might be larger because of lesser Martian gravity. Competent digging tools certainly would be provided on their claws. The chests of these Martian beavers would be larger and their breathing far more active, as there is less oxygen in the air on Mars.

Such beaver-Martians are nothing more than pure speculation, but the idea is based upon the known facts that there is plenty of water on Mars; that vegetation almost certainly exists there; that Mars has no mountains and could scarcely have had an Ice Age; and that evidences of Martian life are not accompanied by signs of intelligence.

Herds of beaver-creatures are at least a more reasonable idea than the familiar fictional one of manlike Martians digging artificial water channels with vast machines or the still more fantastic notion of octopuslike Martians sufficiently intelligent to plan the conquest of the earth.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Apr 02, 2020 -

Comments (5)

Category: Aliens, Animals, Science, 1930s

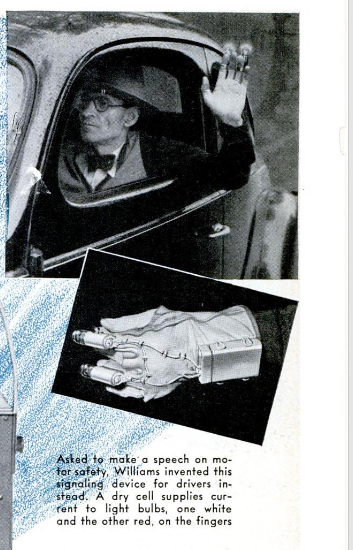

Light-up Traffic Glove

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Mar 25, 2020 -

Comments (5)

Category: Inventions, 1930s, Cars

Pigeon-Killing Death Ray

Dr. Antonio Longoria claimed that he had invented a death-ray. In tests it demonstrated the ability to kill pigeons at a distance of four miles. However, he destroyed his machine and vowed never to build another, insisting that he was “interested now only in doing something to help civilization.”

Spokane Chronicle - Oct 11, 1939

Tampa Tribune - Oct 13, 1939

Posted By: Alex - Fri Mar 06, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: 1920s, 1930s, Weapons

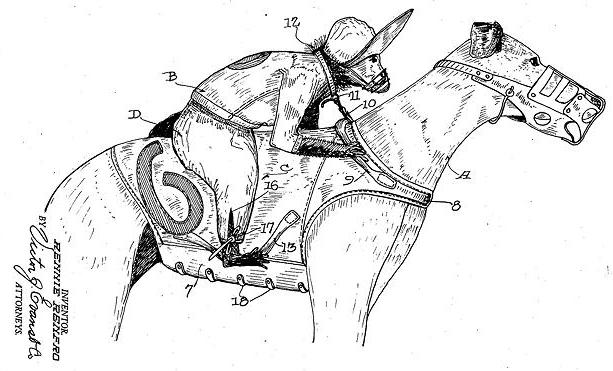

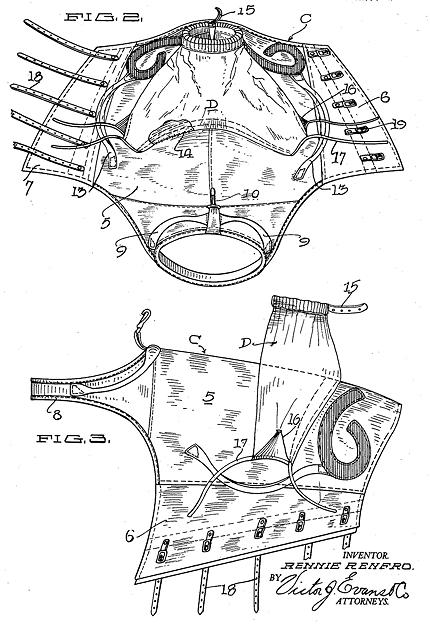

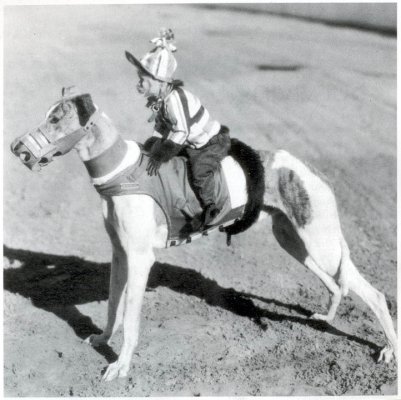

Monkey jockeys race greyhounds

In the early 1930s, a new feature was introduced at some greyhound races: monkey jockeys. Apparently the crowds loved the idea. The problem was, the monkeys had trouble staying on the backs of the greyhounds. Animal trainer Rennie Renfro came up with a solution — a special harness that would tie the monkey onto the back of the dog. Renfro patented his invention in 1933.It probably made him some money, because I can find descriptions of races with monkey jockeys for decades afterwards.

Rennie Renfro (left) and his wife

St. Louis Post Dispatch - July 2, 1933

image source: Greyhound Articles Online

Posted By: Alex - Sun Mar 01, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Sports, 1930s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |