1940s

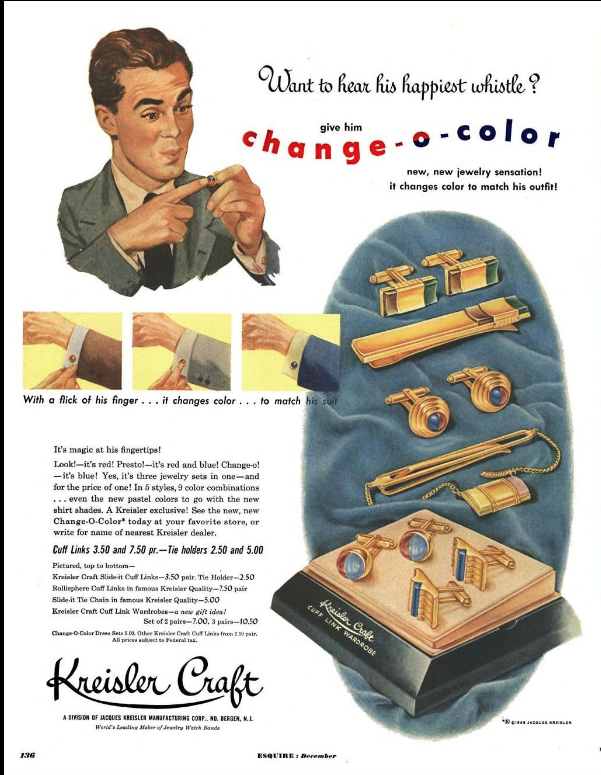

Change-o-Color Men’s Jewelry

For the 1949 Metrosexual. But, alas, did not catch on.

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Aug 04, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Jewelry, 1940s, Men

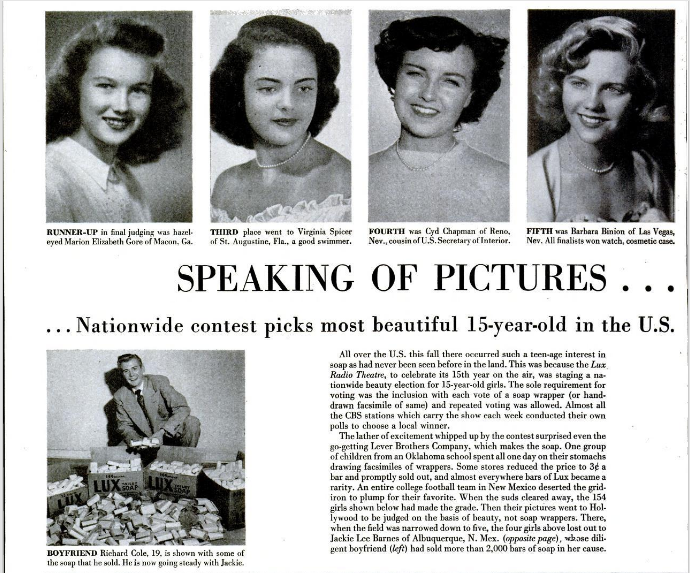

The LUX RADIO THEATRE “Most Beautiful 15-Year-old Contest”

Part of our "strange beauty contest" series.It seems highly unlikely that any company could stage this today.

Full article here.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jul 23, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Contests, Races and Other Competitions, Radio, 1940s

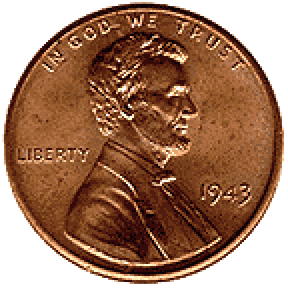

The rare 1943 copper penny

1943 copper pennies are among the most-sought after coins by collectors. In 2010, one of them sold for $1.7 million. Although around $200,000 seems to be what most of them fetch.

The reason for their value is that so few of them exist. In 1943, due to the war, pennies were made out of zinc-coated steel. But somehow approximately 40 copper ones were made by accident.

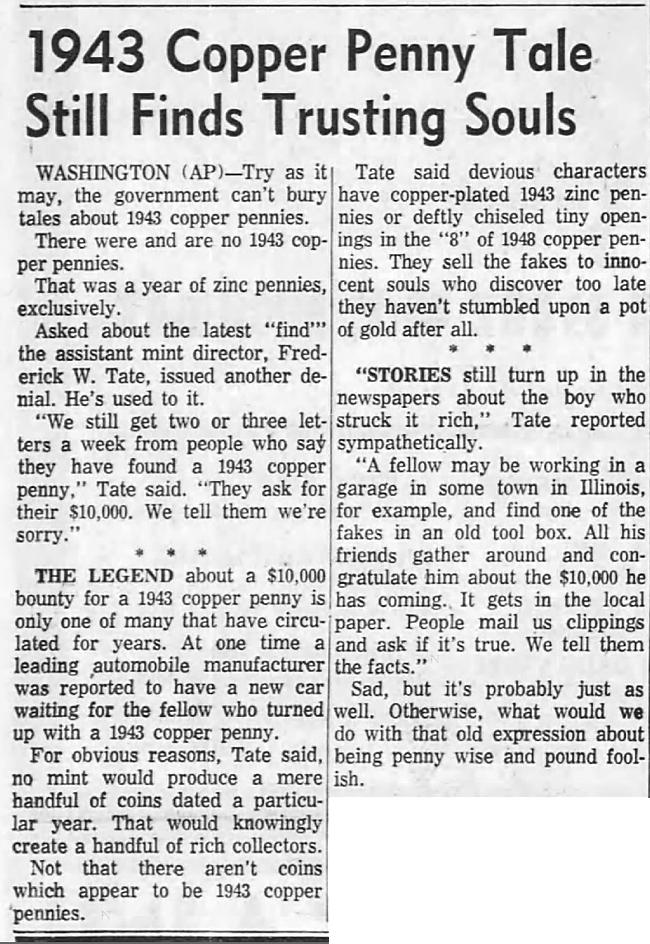

For several decades the US Mint denied the existence of 1943 copper pennies (see news clipping below). It wasn't until a few showed up, and were authenticated by experts, that the mint changed its tune. Now it states:

Some strange rumors have circulated about the 1943 copper pennies. Such as that if you found one the Ford motor company would give you a free car. Not true, though if you find one, you could afford to buy quite a few cars. And a few of these pennies are potentially still in circulation.

More info: definition.org

Battle Creek Enquirer - Mar 7, 1963

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jul 13, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Money, Collectors, 1940s

Follies of the Madmen #480

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jun 18, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Ambiguity, Uncertainty and Deliberate Obscurity, Business, Advertising, Daredevils, Stuntpeople and Thrillseekers, Fashion, 1940s

The Glmite Bomb

Before the atomic bomb, other "super bombs" were dreamed up and invented. One of the more notorious was Lester Barlow's Glmite Bomb. Barlow claimed it could kill everything within a 1000-yard radius, but when the U.S. military tested it in 1940, exploding it in a field surrounded by goats, it failed to kill, or even injure, a single goat.Glmite also has to be one of the worst names ever for an explosive. It was created by combining the words 'Glenn' and 'Dynamite'.

More details from The Ordnance Department: Procurement and Supply, by Harry Thomson and Lida Mayo —

Tests of the Barlow bomb took up a good deal of the time of Ordnance planners in April and May, extending down into the most anxious weeks in May. When the newspapers announced that goats would be tethered at varying distances from the bomb to determine its lethal effects, Congress and the War Department were deluged with letters of protest from humane societies and private citizens. All the concern turned out to be wasted. At the first test, the bomb leaked and did not go off; at the second, held at Aberdeen Proving Ground in late May, the explosion occurred, but the goats, unharmed, continued to nibble the Maryland grass.

Barlow supervising the set up of the Glmite Bomb.

The Algone Upper Des Moines - June 18, 1940

Explosion of the Glmite Bomb at Aberdeen Proving Ground

Note the goats in the right foreground, unharmed

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jun 09, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: 1940s, Weapons

Follies of the Madmen #478

The horrifying Hotpoint Corporate Spokesbeing, with a giant Hotpoint logo wedged into its brain, appears to a mother and child.

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jun 01, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Aliens, Business, Advertising, Corporate Mascots, Icons and Spokesbeings, Domestic, Surrealism, 1940s, Brain Damage

Exercise Wings

Richard Burgess's 1941 patent (No. 2,244,444) describes a pair of feathered wings that could be attached to the arms of an individual, who would then flap the wings up and down. This, claimed Burgess, would create a sense of buoyancy, while simultaneously providing physical exercise. In particular, it would "develop the chest, back, arm and leg muscles, while also tending to create accelerated breathing and thus general physical tone." It would do all this, he said, while also being "very diverting and accordingly attractive."How did this product never take off?

Posted By: Alex - Sun May 10, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Exercise and Fitness, Inventions, Patents, 1940s

Undies Are Gossips!

LUX Soap's 1942 ad campaign warned of the danger of talking underwear.

Some analysis by Melissa McEuen in Making War, Making Women: Femininity and Duty on the American Home Front:

The "Undies Are Gossips" campaign radiated a core message familiar to Americans early in the war: the power of talk. U.S. government propaganda connected conversations with death and destruction for U.S. troops: "Somebody blabbed — button your lip!" and "A Careless Word… A Needless Sinking" warned viewers to check their conversations. One resonant quip suggested "Loose Lips Might Sink Ships."

Spokesman Review - Mar 1, 1942

Philadelphia Inquirer - July 19, 1942

Posted By: Alex - Sat Apr 25, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Advertising, Underwear, 1940s

Shreddies vs. Shredded Wheat

Source of ad.

The Wikipedia entries for Shredded Wheat and Shreddies fail to explain the overlapping existence of two identical cereals from the originator, Nabisco. Much investigation needs to be done. Was one more for the Canadian market?

Posted By: Paul - Fri Apr 24, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Advertising, Cereal, 1940s, North America

The Cleve Cartmill Affair

Science-fiction author Cleve Cartmill is best known for his short story "Deadline," which appeared in the March 1944 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. The story isn't famous because it's a good story. Cartmill himself described it as a "stinker." It's famous because it contained specific details about how to make an atomic bomb — details which Cartmill somehow knew over a year before the existence of the bomb had been revealed by the U.S. government.When Military Intelligence learned about the story they freaked out, fearing a security breach, and launched an investigation. They questioned Cartmill, as well as Astounding editor John W. Campbell. But eventually they concluded that Cartmill had gained his info, as he insisted, from publicly available sources.

However, the rumor is that Military Intelligence bought up as many copies of that issue of the magazine as they could, to prevent its dissemination. Which makes that issue quite valuable. For instance, at Burnside Rare Books it's going for $400.

But if you simply want to read the issue (and Cartmill's story), you can do that at archive.org for free.

More info: lynceans.org, Wikipedia.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Apr 10, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, Science Fiction, 1940s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |