1950s

The Many Lives of the Borden’s Cows

Would today's media consumers accept bobbing paper cutouts in place of CGI?

Posted By: Paul - Sun Jun 04, 2017 -

Comments (1)

Category: Anthropomorphism, Business, Advertising, Products, Food, 1950s

Follies of the Madmen #316

I always take my sleep advice from Big Steel.

Original ad here.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jun 01, 2017 -

Comments (2)

Category: Business, Advertising, Products, Domestic, Dreams and Nightmares, 1950s

Lloyd Thomas Koritz — Human Guinea Pig

As a young doctor-in-training at the University of Illinois Medical School in the early 1950s, Lloyd Thomas Koritz volunteered to be a guinea pig in a variety of experiments. In one, he ate a pound of raw liver daily (washed down by a quart of milk) to help study liver metabolism. In a fatigue study he was kept unconscious for 11 hours.But the most dangerous experiment involved being hung in a harness from a specially-constructed mast and knocked out with anesthesia and curare, so that his breathing stopped. Researchers then tested methods of resuscitating him. They were searching for more efficient ways of resuscitating electrocuted power line workers, so that they could revive the workers while they were still hanging from the poles instead of having to lower them while unconscious to the ground, which takes a lot of time.

I think it would be hard nowadays to get approval to do these kinds of tests on human subjects. Koritz said he disliked the liver-eating experiment the most. In 1953 he was given the Walter Reed Society Award for being willing to repeatedly risk his life for the sake of science.

"Drugged into unconsciousness and paralysis, [Koritz] willingly risked insanity

and death in a significant experiment. This test helped determine the best way

to revive electrically-shocked linemen."

Saturday Evening Post - July 25, 1953

San Bernardino County Sun - Apr 9, 1953

San Bernardino County Sun - Apr 9, 1953

Posted By: Alex - Tue May 23, 2017 -

Comments (8)

Category: Science, Experiments, 1950s

Looking For Girls

One for the strange excuses file.

Freeport Journal Standard - Apr 26, 1954

Posted By: Alex - Mon May 22, 2017 -

Comments (0)

Category: 1950s

Mildred Our Choir Director

Posted By: Paul - Wed May 10, 2017 -

Comments (3)

Category: Humor, Music, 1950s

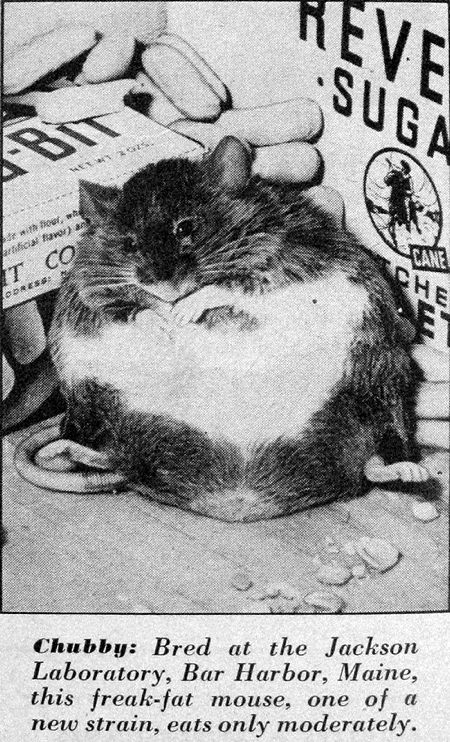

Obese, the Freak Fat Mouse

A fat mouse that was bred at Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine during the late 1940s/early 1950s. The researchers called him "Obese," or "O.B." for short. As in, that was his name, not just a description of what he was. Fat mice bred from Obese were used in the study of diabetes and obesity.

Newsweek - Apr 2, 1951

Ellen Ruppel Shell tells the story of Obese in her book The Hungry Gene: The Inside Story of the Obesity Industry:

An animal caretaker first spotted the creature huddled in a corner of its cage, grooming itself. It was furrier than most, but what really stood out was the size of the thing — it was hugely fat. The caretaker alerted doctoral candidate Margaret Dickie, who diagnosed the mouse as "pregnant." But there were problems with this theory. For one thing, the mouse never delivered a baby. And on closer inspection, it turned out to be male. The fat mouse ate three times the chow eaten by a normal mouse, pawing for hours at the bar of the food dispenser like an embittered gambler banging away at a recalcitrant slot machine. Between feedings it sat inert. It seemed to have been placed on this earth for no other purpose than to grow fat.

There had been other fat mice. The agouti mouse, named for its mottled yellow fur similar to that of the burrowing South American rodent, is, in its "lethal yellow" mutation, double the weight of the ordinary variety. But the fat agouti was svelte compared to the newcomer. This mouse was outlandish, a joke, a blob of fur splayed out on four dainty paws like a blimp on tricycle wheels. Rather than dart around the cage in mousy abandon, it was docile, phlegmatic, as though resigned to some unspeakable fate. Dickie and her colleagues christened the mouse "obese," later abbreviated to "ob," and pronounced "O.B.," each letter drawn out in its own languid syllable.

Posted By: Alex - Mon May 08, 2017 -

Comments (2)

Category: Animals, Science, 1940s, 1950s

Holcombe’s Mechanical Partner

I'd like to see this gadget in action. Unfortunately I can't find any videos of it.It doesn't seem to have survived past 1954.

LA Times - July 1, 1954

Posted By: Alex - Sun May 07, 2017 -

Comments (4)

Category: Inventions, 1950s, Dance

A Word to the Wives

Posted By: Paul - Sat May 06, 2017 -

Comments (0)

Category: Domestic, Family, Stereotypes and Cliches, 1950s

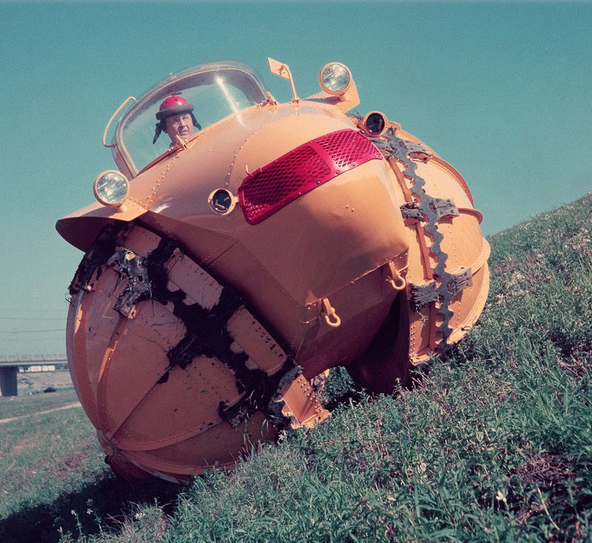

The Rhino

More info here.

1954 coverage here.

Posted By: Paul - Thu May 04, 2017 -

Comments (0)

Category: Inventions, Motor Vehicles, 1950s

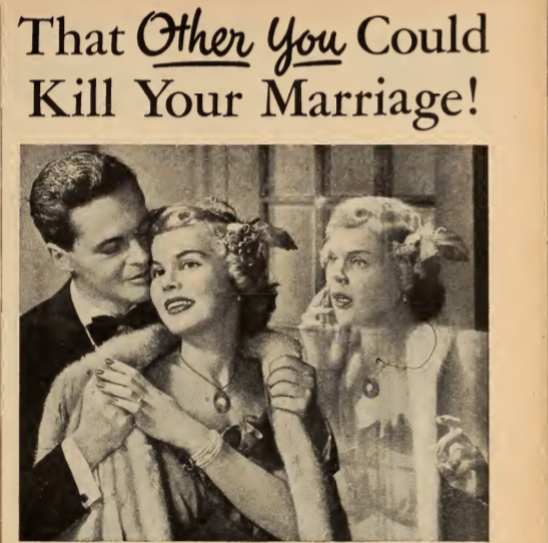

Mystery Illustration 44

What is this woman's domestic sin? Unable to make coffee? Wears curlers to bed? Bad breath?

Answer after the jump.

More in extended >>

Posted By: Paul - Tue May 02, 2017 -

Comments (7)

Category: Annoying Things, Business, Advertising, Products, Domestic, 1950s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |