1960s

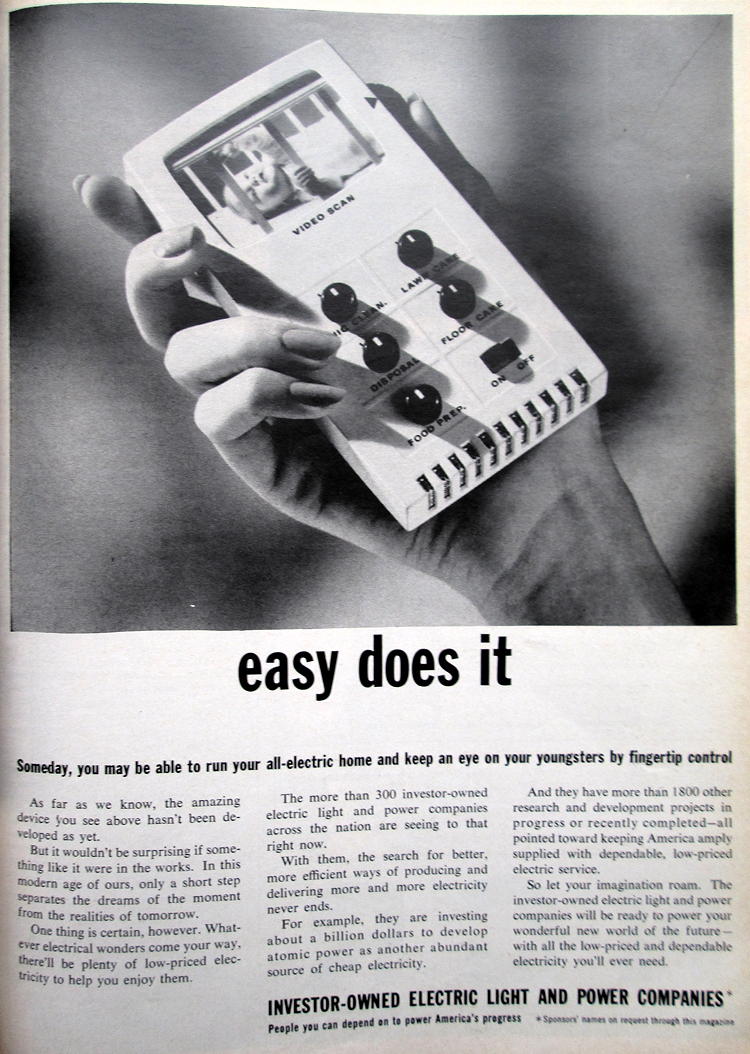

Home Monitor of the Future

This 1964 ad envisioned a hand-held device that would allow people to run their home by remote control:Someday, you may be able to run your all-electric home and keep an eye on your youngsters by fingertip control

As far as we know, the amazing device you see above hasn't been developed as yet.

But it wouldn't be surprising if something like it were in the works. In this modern age of ours, only a short step separates the dreams of the moment from the realities of tomorrow.

Newsweek - July 1964

For once, the future actually delivered, since a smartphone can do everything imagined in this ad, and more.

Interesting that the gadget has controls for 'lawn care,' 'food prep,' etc., but not for turning the lights on.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Nov 17, 2020 -

Comments (5)

Category: 1960s, Yesterday’s Tomorrows

To Be Alive

Moments of surreal or bizarre imagery in a nice little film about enjoying life.

One weird addendum: you are seeing only one-third of the film. The film was meant to run on three screens simultaneously, with different imagery on each screen, although sometimes, I think, they synchronized.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Nov 15, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Movies, Documentaries, Philosophy, Surrealism, 1960s

Help, I’m a Rock!

Their Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Nov 08, 2020 -

Comments (6)

Category: Music, Nature, Avant Garde, Surrealism, 1960s

Rodney Fertel’s Gorilla Campaign

1969: Rodney Fertel ran for mayor of New Orleans on what he called the "primate platform". He promised that, if elected, he would "Get a gorilla for the zoo." This was his primary campaign issue. He campaigned by standing on street corners, sometimes dressed in a safari outfit, sometimes in a gorilla suit, handing out miniature plastic gorillas to passers-by.

Rodney Fertel with a baby gorilla

Fertel lost the election, receiving only 310 votes, but he kept his promise by donating a pair of West African gorillas the following year to New Orleans' Audubon Zoo, at his own expense.

Incidentally, Rodney was the former husband of Ruth Fertel, who founded Ruth's Chris Steak House. Fertel's son has written a book about his parents titled The Gorilla Man and the Empress of Steak: A New Orleans Family Memoir.

More info: nola.com

Posted By: Alex - Tue Nov 03, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Animals, Politics, Strange Candidates, 1960s

I Took a Trip (On a Gemini Spaceship)

The creator's Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Nov 02, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Eccentrics, Music, Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, Outsider Art, 1960s

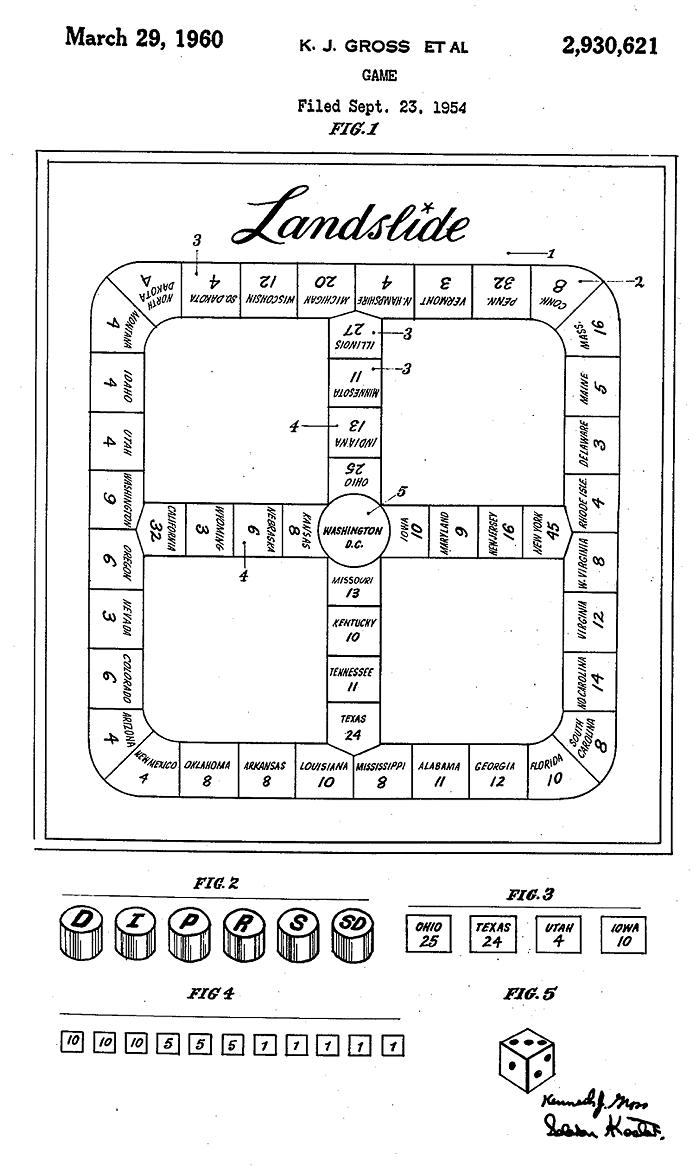

Landslide—the electoral college board game

Kenneth J. Gross and Sebron Koster were granted a patent in 1960 for Landslide, an electoral college board game. Players moved their pieces around the board trying to gain enough electoral college votes to start a 'landslide'. If you want to play it, the rules are below.As far as I can tell, their game was never sold in stores. However, there have been two other board games called Landslide that did make it to market (in 1971 and 2004). Both involved acquiring electoral college votes but were otherwise different than the 1960 version.

At the start of the play of a game each player selects his political party and takes his marker and tokens to match. Each player or candidate rolls the die and the candidate who rolls high die opens the play. He is succeeded in turn by each candidate in a clockwise direction. All candidates begin their campaign from the central segment, viz. Washington, D.C.

The number appearing on the die indicates the number of segments (States) which the candidate may move his marker and the number of electoral votes he wins in the State attained. He places his marker on that State and beside it his tokens corresponding to the number of votes thereby won in that State.

On each turn a candidate may move in any direction he chooses. The choice of routes allowed to candidates enables them to exert an influence on the development of their campaigns. In passing through a junction of three States he may traverse only two of the States in the course of any one move. He may not reverse his direction of movement in the course of one move. A candidate may not land on nor pass through a State occupied by another candidate's marker. If the movement of a candidate is blocked by the markers of other candidates in such a manner that he cannot move his marker to the full extent of his throw of the die, then he loses that turn. A candidate must move if possible.

A candidate must return to Washington, D.C. at any time that his throw of the die could place him there, providing that Washington, D.C. is unoccupied.

The number of electoral votes of a State won by a candidate is indicated by his tokens placed alongside that State. The entire electoral vote of a State is won by the first candidate to obtain a majority of the electoral votes of that State. When a State is won by a candidate he removes the card of that State and all the electoral vote tokens on that State are returned to their respective candidates.

States that have not been won are indicated by the presence of the State cards still beside them. Any candidate may land on a State that has been won by another candidate irrespective of the presence or absence of electoral votes remaining unacquired.

Whenever a candidate lands on Washington, D.C., he has the right to call a “caucus' if he so desires. When a caucus is declared all candidates count, the electoral votes of the States they have won completely, as indicated by the State cards in their possession. The outstanding electoral votes relating to States not yet won are also counted. Should the candidate with the least number of electoral votes be unable to win the election even by winning all the electoral votes of the States which are not yet won completely then he is eliminated as a presidential candidate. Only one candidate may be eliminated on each caucus.

If on the calling of a caucus, the tally of electoral votes indicates that every candidate still has a chance to win the election assuming his acquisition of all outstanding electoral votes, then the candidate calling the caucus loses all his electoral votes on States not won completely; that is he removes all his electoral vote tokens from the board.

The electoral vote tokens of the eliminated presidential candidate on the States not completely won are removed from the board. The electoral votes of the States completely won by the eliminated candidate are divided among the remaining candidates according to the geographical distribution set out in the table above. In other words the candidate with the most electoral votes from the Eastern States, takes all the Eastern States from the eliminated candidate and similarly for the other geographical groups of States.

The presidential election is won by the first candidate who captures 266 or more electoral votes.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Nov 01, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Games, Politics, Patents, 1960s

Hors-d’oeuvre

Hors-d'oeuvre, Jeff Hale,

Some interesting animation from the interface of the Fifties and Sixties.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Oct 30, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: PSA’s, Cartoons, 1950s, 1960s

Twenty Minutes of 1960s Hygiene Commercials

If all these products had been properly employed, Americans would have had perfect lives!

Posted By: Paul - Fri Oct 23, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Business, Advertising, Hygiene, 1960s, Hair and Hairstyling

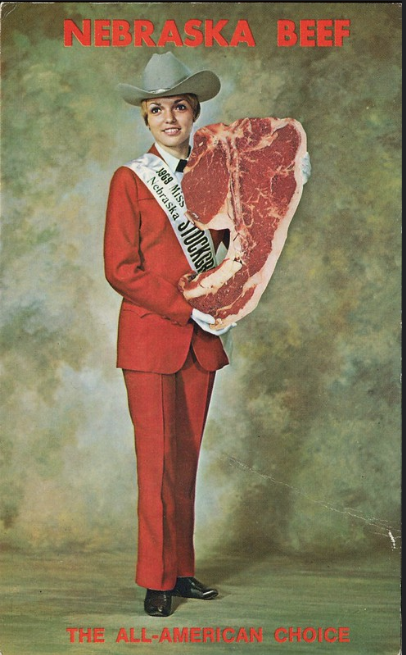

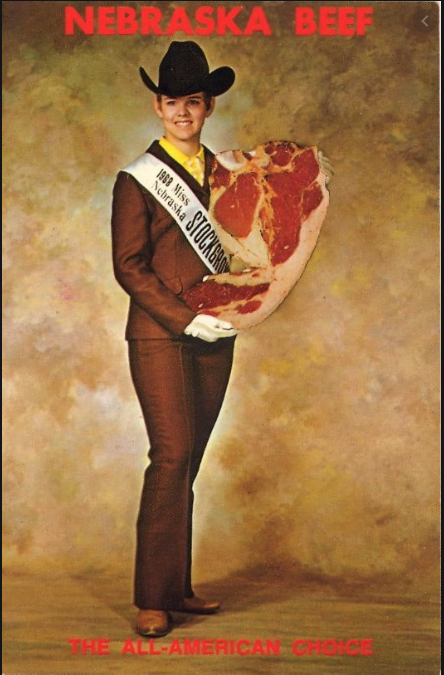

Miss Nebraska Stockgrower

Posted By: Paul - Tue Oct 20, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Food, Regionalism, 1960s, 1970s

How to raise a genius

According to Harold G. McCurdy, a professor at the University of North Carolina, the first step was to not send your kids to public school.Not that he had anything against public schools, having sent his own kids to one. And he questioned whether raising kids to be geniuses was a desireable goal, since he believed that geniuses often led isolated, unhappy lives.

Nevertheless, based on his study of the childhoods of 29 geniuses, conducted back in 1960, he determined that "three striking factors seemed to be typical of the childhood pattern of genius":

"Public school education," he declared, "works against these three things."

Apparently McCurdy's study has been embraced by some proponents of home schooling. Although I don't get the sense that it was his intention to promote that.

You can read McCurdy's full study here: The Childhood Pattern of Genius

The Oklahoma Daily - Feb 17, 1961

Posted By: Alex - Thu Oct 15, 2020 -

Comments (5)

Category: Education, Intelligence, School, 1960s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |