1960s

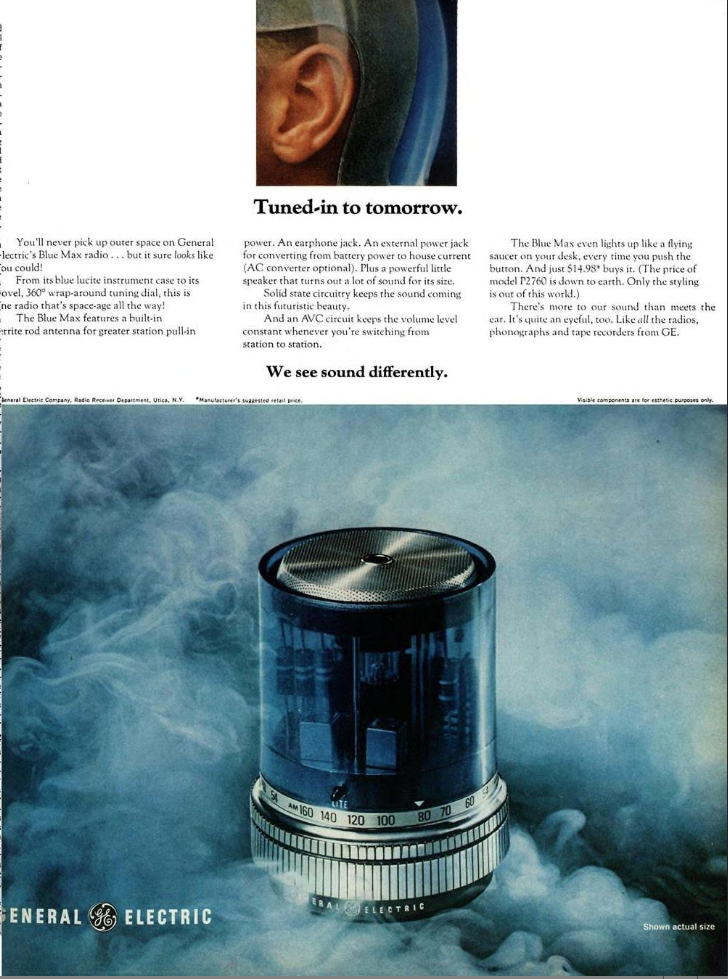

The GE Blue Max Radio

Posted By: Paul - Thu Aug 01, 2019 -

Comments (3)

Category: Design and Designers, Inventions, Technology, 1960s

The Air-Conditioning Show

In 1966, the art group Art & Language (which, at the time, was Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin) debuted the Air-Conditioning Show. This consisted of an air conditioner in an empty room. The only vaguely art-like part of the exhibit (in a conventional sense) was ten sheets of paper pinned to the wall by the door, on which were written line after line of cryptic sentences, such as, "It is obvious that the elements of a given framework (and this includes the constitution of construct contexts) are not at all bound to an eliminative specifying system."This exhibit is now regarded as a significant moment in the development of modern art. One art historian noted that what made it original was that, "the body of air in a particular gallery space was singled out for art-status." Another says:

In a 2012 article in the Independent, Charles Derwent singled it out as, "the moment when the visual arts in Britain were beginning to turn un-visual, when mere visuality was becoming suspect."

The sheets of paper are now preserved at the Tate Museum of Modern Art.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jul 30, 2019 -

Comments (2)

Category: Art, 1960s

George Price and Altruism

During the 1960s, scientist George Price came up with a mathematical formula to explain the evolution of altruism. This equation has been described as "the closest thing biology has to E=mc2."Legend has it that Price subsequently became obsessed by proving that altruism was a genuine phenomenon, extending beyond family relations. He did this by giving away all his possessions to random, needy people — to the point that he himself became penniless, was evicted from his apartment, and after living in various squats throughout London, eventually committed suicide.

That's the legend, but Laura Farnworth discovered that, while the story is basically true, there's slightly more to it than that. Such as that Price was also suffering from psychotic delusions. Read more at nautil.us.

George Price

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jul 23, 2019 -

Comments (1)

Category: Eccentrics, Mad Scientists, Evil Geniuses, Insane Villains, 1960s

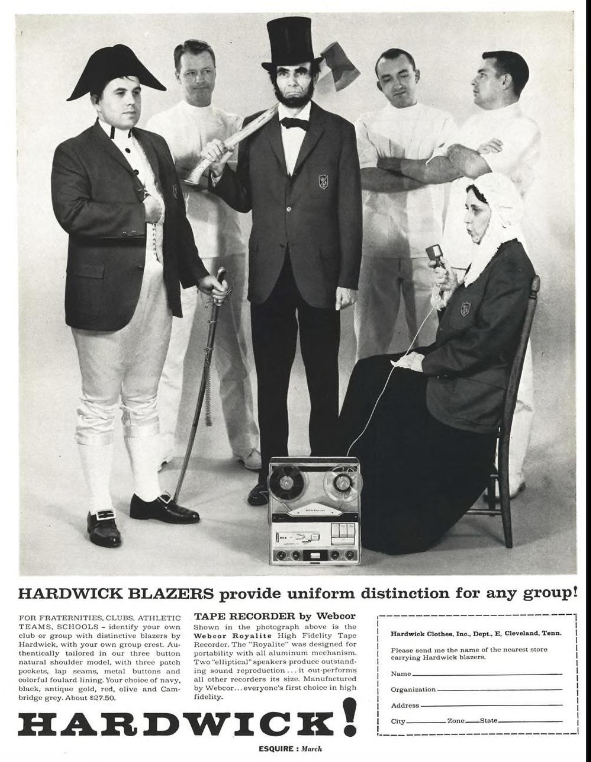

Follies of the Madmen #436

Those are plainly loony bin attendants in the background, denoting that this clothing line is worn by crazy people. Gratuitous tape recorder also puzzling.

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jul 22, 2019 -

Comments (5)

Category: Business, Advertising, Fashion, 1960s, Brain Damage

Warhol Flies Braniff

Posted By: Paul - Sun Jul 21, 2019 -

Comments (1)

Category: Art, Avant Garde, Business, Advertising, Air Travel and Airlines, 1960s

I Dreamt I Saw Khrushchev (in a Pink Cadillac)

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jul 15, 2019 -

Comments (1)

Category: Humor, Music, Politics, 1960s, Russia, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

Sebastian Cabot’s “Like A Rolling Stone”

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jul 11, 2019 -

Comments (0)

Category: Ineptness, Crudity, Talentlessness, Kitsch, and Bad Art, Music, 1960s, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

Colgate Kitchen Entrees

One of the classic brand-extension blunders of all time has to be when toothpaste-maker Colgate decided to come out with a line of frozen dinners. The story is told in many places, and it's usually described as having occurred in 1982. For instance, here's the HuffPost's take on it:Lots of other sites refer to this as having happened in 1982, such as here, here, and here. But when I took a closer look at the story I couldn't find any primary sources from 1982 about it. But there are several 1960s-era sources (Washington Food Report, Weekly Digest) that refer to Colgate having test-marketed a line of frozen dinners in Madison, Wisconsin in 1964. A 1966 article in Television Age magazine offered some insight into what inspired the company to do this:

So, unless someone can find some primary sources that indicate otherwise, I'm going to assume that the Colgate Kitchen debacle actually happened in 1964, not 1982. And it was only a test-marketing trial run, not a full product roll-out. It would definitely be bizarre if, after the 1964 failure, Colgate tried the same thing again in 1982.

There's a couple of images of Colgate Kitchen entrees floating around the Internet, but I think they're all photoshops or mock-ups. For instance, the one below is a recent mock-up created by the Museum of Failure in Sweden.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jul 08, 2019 -

Comments (9)

Category: Business, Products, 1960s

The Rockin’ Ramrods, “Don’t Fool With Fu Manchu”

Posted By: Paul - Sun Jul 07, 2019 -

Comments (1)

Category: Literature, Mad Scientists, Evil Geniuses, Insane Villains, Music, 1960s

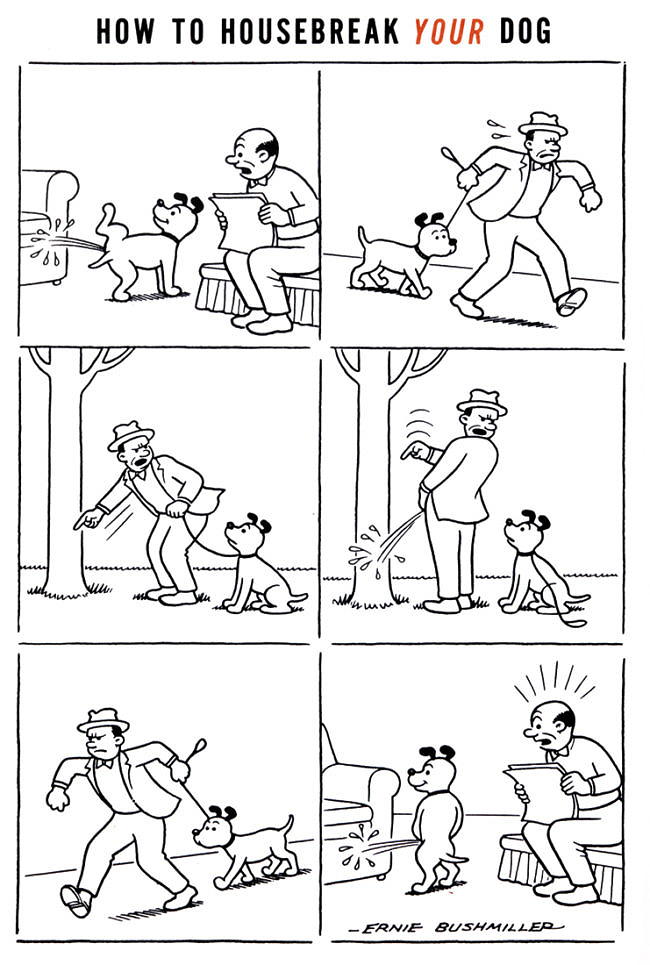

How to housebreak your dog

Ernie Bushmiller is best known as the creator of the Nancy comic strip, which was known for being very wholesome. But it turns out that his most popular and frequently reproduced cartoon, by a wide margin, was a slightly off-color one that he drew in 1961, and which was included that year in the Duch Treat Club Yearbook. He titled it "How to housebreak your dog."The Comics Journal details the many lives of this cartoon, noting:

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jul 06, 2019 -

Comments (3)

Category: Comics, Dogs, 1960s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |