1960s

The scientist who feared inhaling beer cans

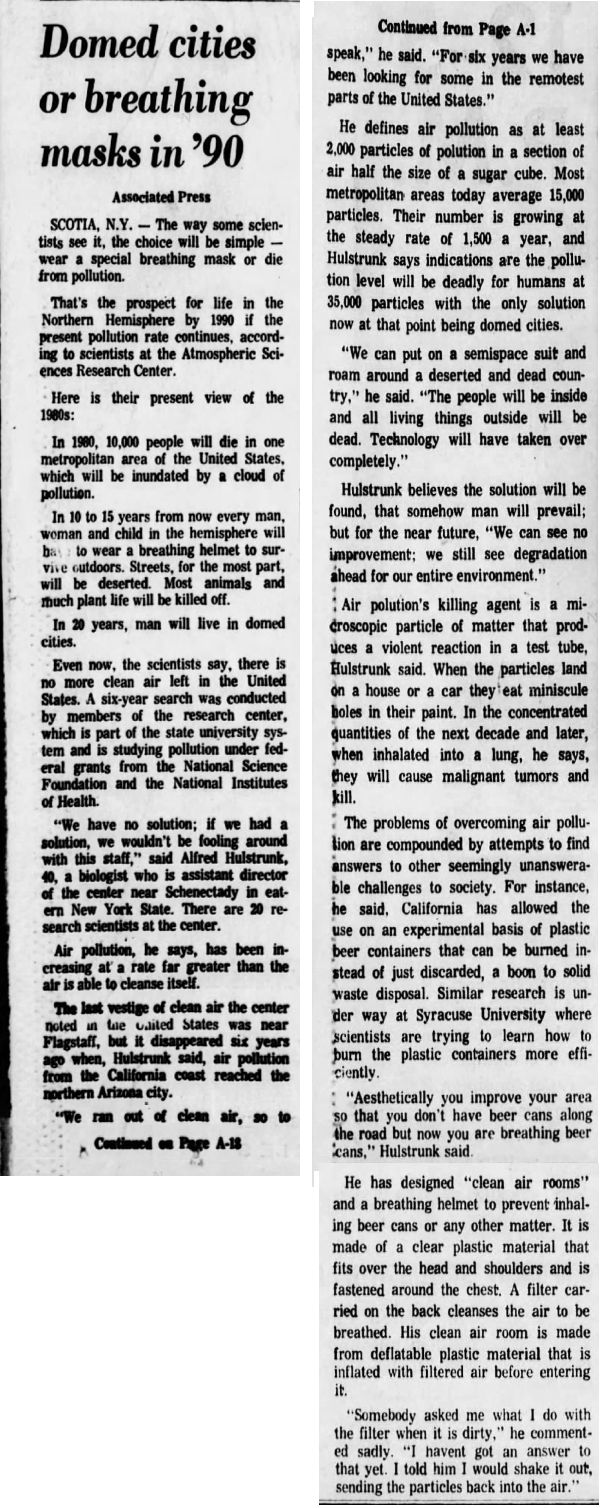

Back in 1969, air-pollution researcher Alfred Hulstrunk had arrived at the pessimistic conclusion that pollution levels were getting so bad that within 10 to 15 years every man, woman, and child would need to wear a breathing helmet to survive outdoors. And within 20 years, he predicted, everyone would have to live in domed cities.Part of the problem, Hulstrunk believed, was all the stuff that society produced, such as "plastic beer containers that can be burned instead of just discarded." When burned, the beer cans added to air pollution. He noted, "Aesthetically you improve your area so that you don't have beer cans along the road, but now you are breathing beer cans."

Therefore, Hulstrunk had prepared for the future by designing an air pollution survival suit "to prevent inhaling beer cans or any other matter."

Corsicana Daily Sun - Dec 23, 1969

Arizona Republic - Dec 21, 1969

Note: It looks like Hulstrunk is still around, now aged 90. He recently gave a talk at Cedars of Lebanon State Park.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 08, 2016 -

Comments (8)

Category: Predictions, Yesterday’s Tomorrows, Science, 1960s

Joey Reynolds and the Beatles

An ancient manufactured pop-music feud.

The Joey Reynolds story here.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Aug 08, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Law, Music, Rivalries, Feuds and Grudges, 1960s

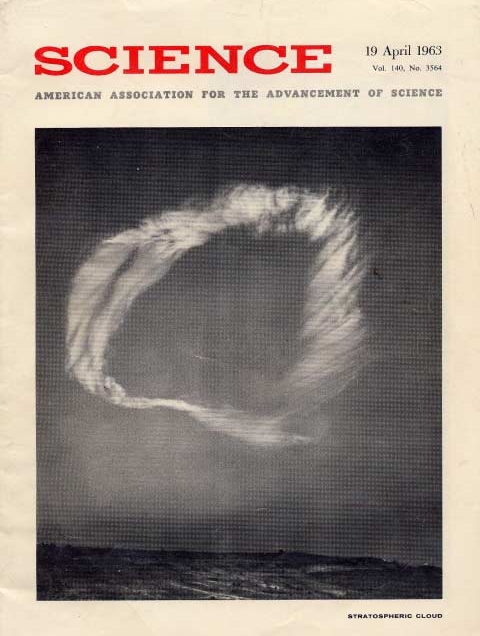

The Jesus Cloud of 1963

This strange cloud appeared over Arizona in 1963 and inspired many mystical revelations.

Good coverage here.

And here.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Aug 06, 2016 -

Comments (3)

Category: Eccentrics, Nature, Religion, 1960s

Suddenly hated money

The recurring weird-news theme of people who destroy large amounts of money for various reasons (usually so that their heirs can't get their hands on it).

The Wilmington News Journal - Jan 8, 1963

LONDON — Mrs. Doris Lilian Hawtree, 46, told a magistrate's court yesterday she tore up $700 after a quarrel with her daughter's mother-in-law made her suddenly "hate money."

Posted By: Alex - Fri Aug 05, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Money, 1960s

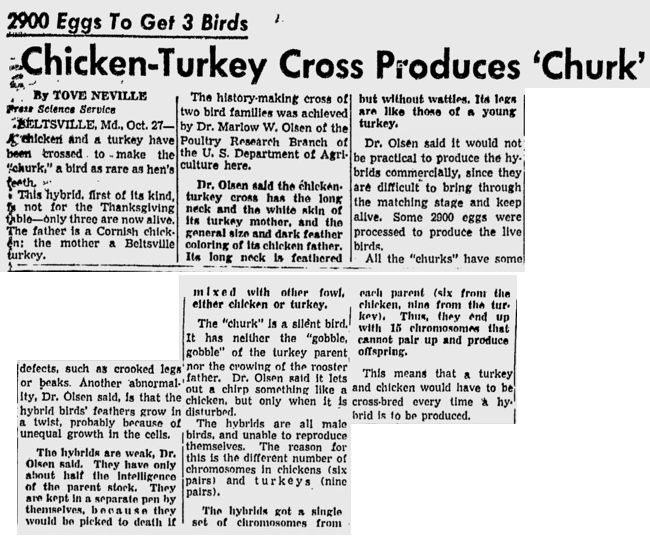

Churks

In 1960, scientists with the poultry research branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced that they had successfully created a chicken-turkey hybrid. They called the new bird a "churk." It was the first time such a cross had ever successfully been achieved — one of the obstacles being that chickens have six pairs of chromosomes, and turkeys have nine pairs. Churks ended up having 15 chromosomes.The scientists created three male churks. These three were not only the first, but also apparently the last of their kind.

Some features of the churk:

- They suffered from mental retardation, having only half the intelligence of either chickens or turkeys.

- They were mostly silent, only letting out a feeble chirp if disturbed.

- They had the long neck, legs, and white skin of a turkey, but the general size and coloring of a chicken.

- Their feathers grew twisted.

- All three churks had some defects, such as crooked legs or beaks.

- They had to be kept in a separate pen from the chickens and turkeys, to prevent them from being pecked to death.

More info: Science News (Nov 22, 2011)

The Pittsburgh Press - Oct 27, 1960

Posted By: Alex - Thu Aug 04, 2016 -

Comments (12)

Category: Animals, 1960s

Scopitones

Full story here.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Jul 31, 2016 -

Comments (3)

Category: Music, Video, 1960s

1960s Portable Record Player

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jul 26, 2016 -

Comments (1)

Category: Music, Technology, Teenagers, 1960s

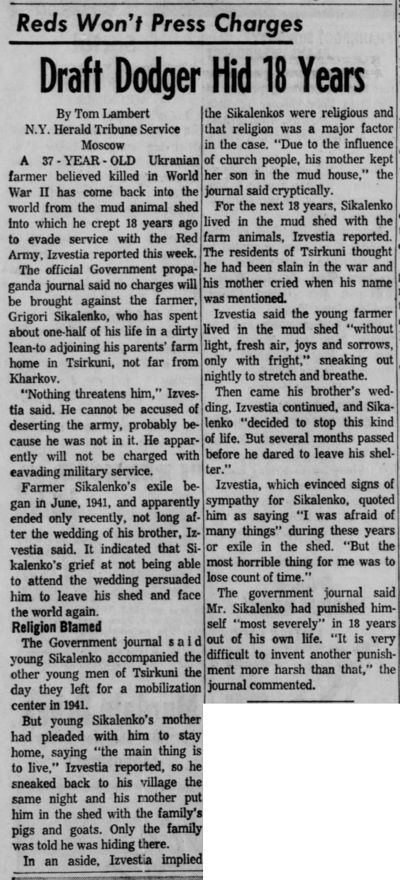

18 years beneath a dung heap

A Ukrainian man, Grigori Sikalenko, spent 18 years hiding under a dung heap in order to avoid serving in the Red Army. He went into hiding in June 1941, at the urging of his mother, who secreted him away "under the manure pile at the back of the family goat shed."He spent 18 years in hiding, until finally, in 1959, at the age of 37, he could stand it no longer and ran into town screaming, "I want to live!"

No charges were brought against him since the authorities decided he had already punished himself "most severely."

Note: The claim that he was hiding under a manure pile comes from Time magazine. But another source (the N.Y. Herald Tribune news service) offered a slightly less sensational description of his hideout, saying that he was simply "in the shed with the family's pigs and goats." Also, news sources give his first name as either Grigori or Grisha.

The Ukrainians seem to have a talent for extreme hiding. From that region also came the case of Olga Frankevich, who reportedly spent 45 years hiding beneath a bed in her sister's house in the village of Vishneve. She went into hiding in 1947, following her father's execution in a Stalinist purge, fearing she was about to suffer the same fate. She emerged in 1992.

Southern Illinoisan - Jan 12, 1960

Like a dead soul out of Gogol, a human figure rose out of a dung heap recently in the Ukrainian village of Tsirkuny, and rushed forth shrieking: "I want to live! I want to work!" Astounded neighbors, reported the Soviet newspaper Izvestia last week, found that the stinking, blinking, sunken-jawed wretch was Grisha Sikalenko, 37, a fellow they all thought had died a hero's death fighting Germans in World War II. In truth, quavered Grisha, he had deserted the very night he marched away to war, sneaked home to the hiding place his parents made for him under the manure pile at the back of the family goat shed.

"Don't mind the goats and the dung," his mother told him. "At least you'll survive." Survive he did—for 18 years in his living grave. Twice a day his mother slipped him food, scarcely paused for a word. In winters he nearly froze, and when the summer heat beat down on his reeking pit, he almost suffocated. Yet only on darkest nights would he surface for air. One night, crawling out for fresh air, he saw crosses on the rooftops and fled back in panic, mistaking the new TV aerials for signs of doom. At last, when his younger brother married and the whole village reveled round him, Grisha under his dunghill cursed the day when cowardice induced him to be buried alive. He spent a few more months screwing up his courage, then surfaced.

Once out, he found that his fears of being punished for desertion were groundless: the statute of limitations for wartime desertion had long since made him immune from prosecution, and besides, added Izvestia charitably, 18 years in a manure pile was punishment enough.

--Time - Jan 18, 1960

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jul 21, 2016 -

Comments (4)

Category: 1960s

Swinging Little Government

Now, THIS is a great campaign song AND party platform. "Our secret weapon will be the Rolling Stones!"

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jul 21, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Government, Music, Bohemians, Beatniks, Hippies and Slackers, 1960s

Follies of the Madmen #288

This was not a model of car that had nine lives.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jul 13, 2016 -

Comments (6)

Category: Business, Advertising, Products, Cats, 1960s, Cars

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |