1970s

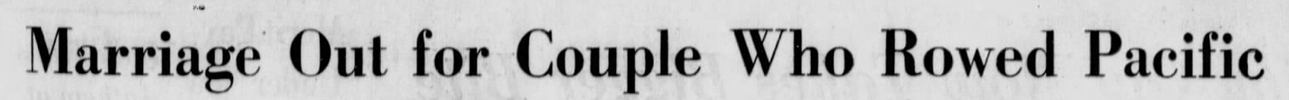

A Year at Sea

Most unique trial for a marriage ever!Source: The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) 23 Apr 1972, Sun Page 3

Posted By: Paul - Mon Apr 11, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Eccentrics, Oceans and Maritime Pursuits, Marriage, 1970s

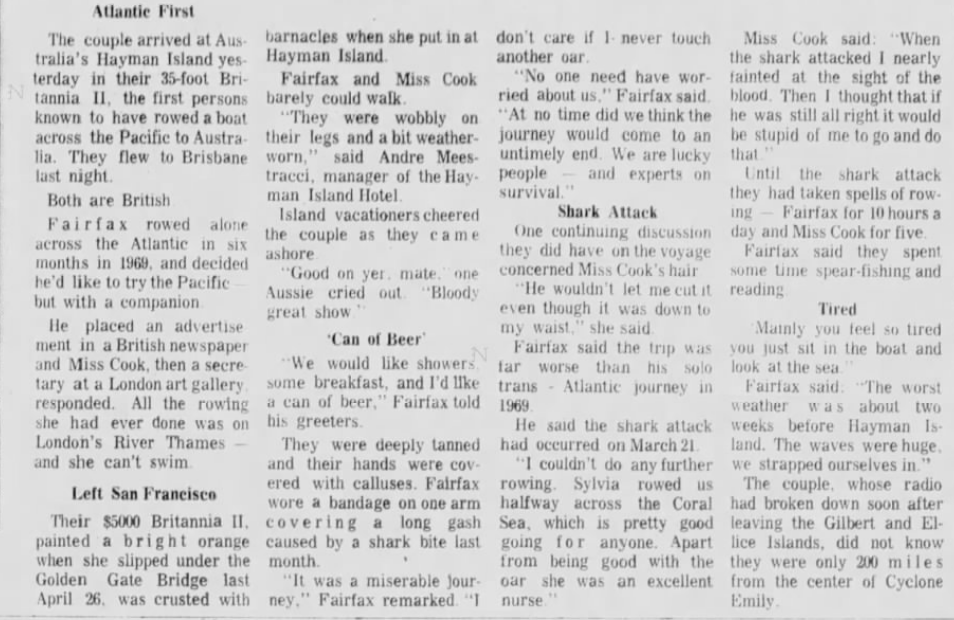

The housewife who became pregnant after watching Uri Geller

March 1974: a Swedish housewife claimed that, after she watched Uri Geller on TV, her contraceptive coil got bent out of shape, thereby causing her to become pregnant.Given that the housewife was never named, I'm going to assume this story sprang from the overly fertile imagination of the "Sunday Mirror Reporter in Stockholm".

Uri Geller references the event in his biography, posted on his website, but gives no more details than are available in the Sunday Mirror story, which suggests that, at the very least, he was never sued by the Swedish housewife.

Sunday London Mirror - Mar 17, 1974

Posted By: Alex - Sun Apr 10, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Paranormal, 1970s, Pregnancy

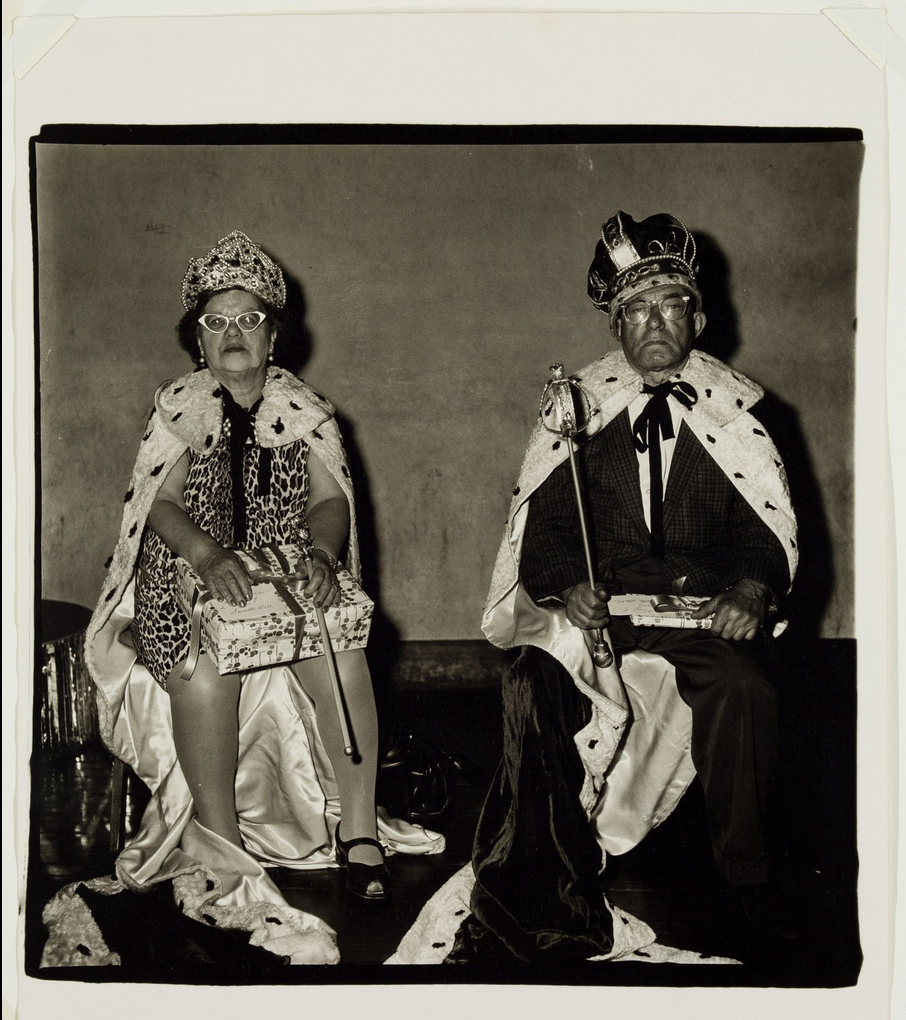

Senior Center King and Queen

A rather more-famous photo to join our legion of "Strange Beauty Queens."

Diane Arbus The King and Queen of a Senior Citizens Dance, N.Y.C., 1970

Posted By: Paul - Wed Apr 06, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Elderly and Seniors, 1970s

Ancient Greek Warrior Sunglasses

NY Daily News - July 25, 1971

For comparison, the helmet of an ancient Greek warrior:

Posted By: Alex - Sat Apr 02, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Fashion, 1970s, Eyes and Vision

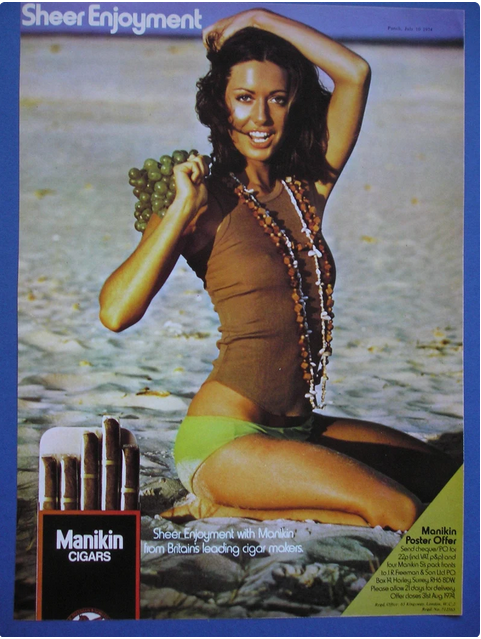

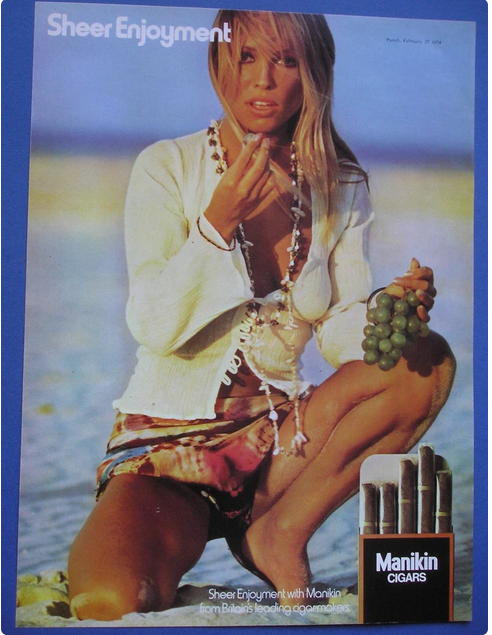

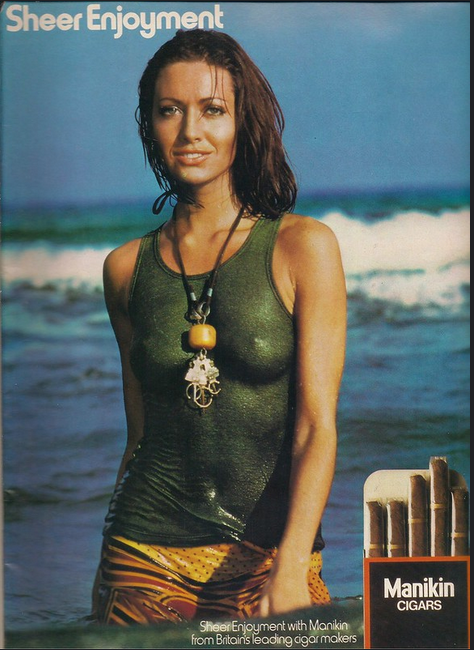

Manikin Cigar Ads

Posted By: Paul - Thu Mar 24, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Innuendo, Double Entendres, Symbolism, Nudge-Nudge-Wink-Wink and Subliminal Messages, Tobacco and Smoking, Advertising, 1970s

Kaliedoscope, “Chocolate Whale”

Their Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Mar 12, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Music, Psychedelic, 1970s

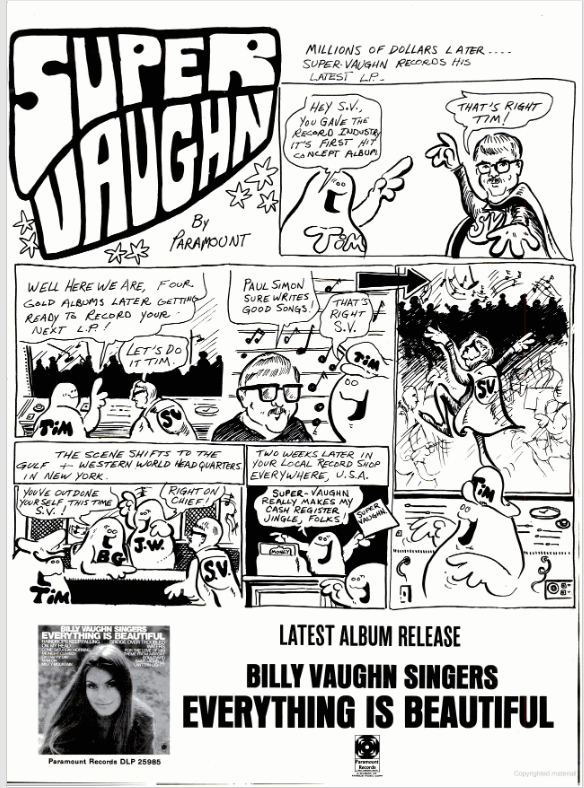

Follies of the Madmen #527

From the "nephew" school of art. "My nephew draws good--we'll get him to do the ad."

Posted By: Paul - Tue Mar 08, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Ineptness, Crudity, Talentlessness, Kitsch, and Bad Art, Music, Advertising, 1970s

Frank P. Reese, light-bulb eater

When they say that the food in prison is awful, I guess that depends on what you like to eat.

Detroit Free Press - Mar 26, 1972

El Paso Times - Mar 25, 1972

Binghamton Press and Sun-Bulletin - Mar 25, 1972

Posted By: Alex - Sun Mar 06, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Prisons, 1970s

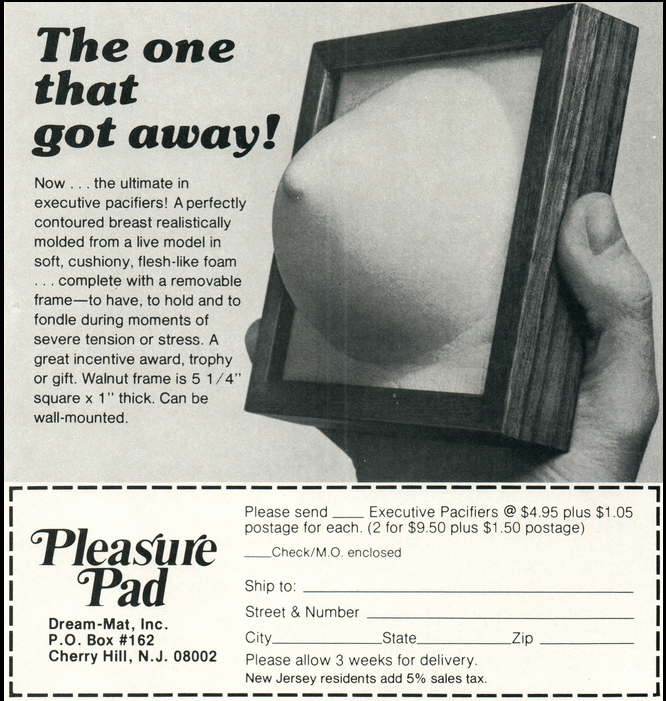

The Pleasure Pad

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Mar 04, 2022 -

Comments (5)

Category: Body, Stereotypes and Cliches, Offices, Business Supplies, Institutional Regulations, 1970s, Women

Robbie the Pulpit Robot

More info: CyberneticZoo.com

Pittsburgh Press - Aug 23, 1973

Posted By: Alex - Wed Mar 02, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Religion, AI, Robots and Other Automatons, 1970s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |