1970s

Skin whitening by intestine shortening

Back in the 1970s, some women in Japan reportedly tried to whiten their skin by having surgery to remove a section of their intestines:Up to 50 inches of the large intestine have to be removed according to Dr. Tadao Yagi, director of a private hospital that specializes in the operation.

I can't imagine why this would work. Perhaps the women grew paler because of malnutrition?

San Francisco Examiner - Mar 26, 1975

I believe these may be photos of the operation being performed, from an article by Tadao Yagi in the Japanese Journal of Medical Instrumentation.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Nov 18, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, Surgery, 1970s

Jello Brainwaves

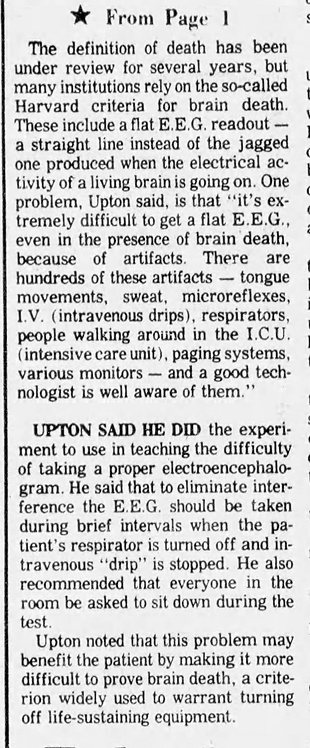

In 1974, Dr. Adrian Upton of McMaster University placed E.E.G. electrodes on a blob of lime jello and obtained positive readings. This indicated brain activity. He published his results in 1976 in the Medical Tribune.Upton was trying to demonstrate that when doctors use an E.E.G. to determine brain death, it can be difficult to obtain a perfectly flat readout, because the equipment picks up stray electrical activity from the surrounding environment. Or maybe he had discovered that jello is a sentient lifeform.

The Jell-O Gallery Museum in Le Roy, New York seems to prefer the latter conclusion. A brain-shaped jello mold on display at the museum bears the message: "A Bowl of Jell-O Gelatin and the Human Brain Have the Same Frequency of Brain Waves."

image source: Donna Goldstein, researchgate.net

More info: The Straight Dope

Wichita Eagle - Mar 8, 1976

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 15, 2021 -

Comments (7)

Category: Food, Jello, Experiments, 1970s, Brain

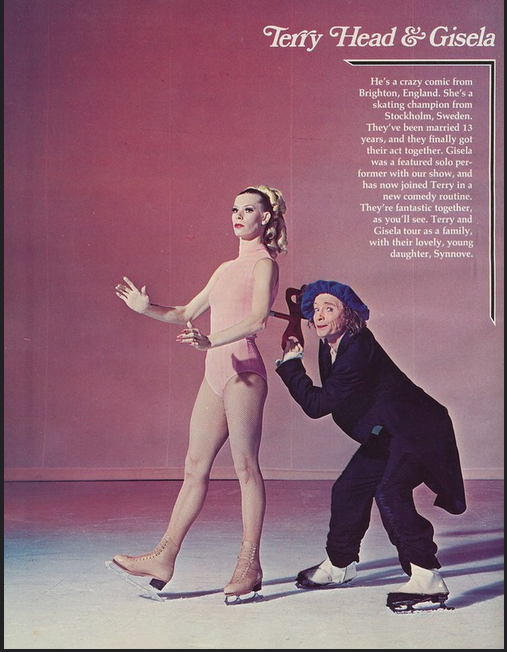

Terry Head and Gisela

It's not every day that one sees a mime-skating-comedy act.Another clip of the act, not embeddable, here on a Facebook page.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Nov 15, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Humor, Puppets and Automatons, Skating, Sledding, Skiing and Other Wintertime Pursuits, 1970s

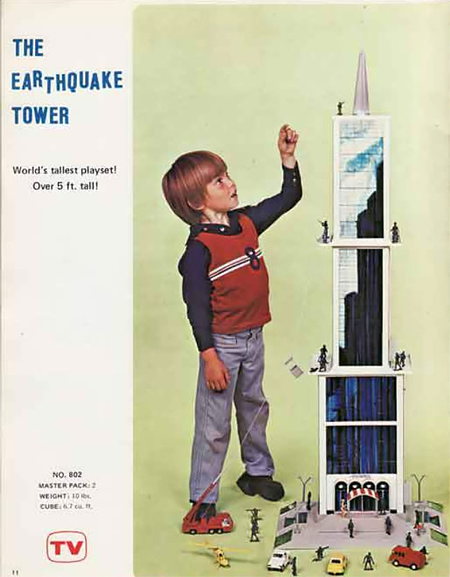

Earthquake Tower

From Remco. It was released in 1976, following the success of the 1974 movies The Towering Inferno and Earthquake. Kids were meant to destroy the skyscraper and then rescue its occupants using the helicopter, firetruck, and team of plastic rescue workers that came with the toy.More info: Design You Trust

Detroit Free Press - Oct 14, 1976

Posted By: Alex - Tue Nov 09, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Disasters, Toys, 1970s

The Gramocar or Record Runner

The Gramocar has gone under a variety of different names: Chorocco, Record Runner, Soundwagon, and Vinyl Killer. But I like Gramocar the best.It was invented in the 1970s by a team at Sony who had the idea that instead of playing a vinyl record by spinning the disc and keeping the needle stationary, it would be possible to keep the disc stationary and move the needle. They designed the moving needle as a miniature VW van, with built-in speakers, that drove in circles around the surface of a record.

Sony got a patent on the invention (US4232202) but was initially reluctant to manufacture it, saying, "We are a hi-fi company, not a toy company." But they changed their mind, and some were sold in Japan. In that way, the Gramocar gained enough of a following that other manufacturers eventually began making them. And you can still buy one today at RecordRunner.jp.

More info: New Scientist - Feb 5, 1981

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 08, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Music, Technology, Patents, 1970s, Cars

Inmate seeks transfer

Specifically, he wanted to be transferred to a woman's prison so that he could "be fruitful and multiply and replenish the earth."He must have figured it didn't hurt to ask.

Miami News - Nov 10, 1971

Posted By: Alex - Sat Nov 06, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Prisons, Gender, 1970s

“Next” by Scott Walker

Although not the writer of the tune, Scott Walker really sells this tale of soldiers and hookers.

His Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Nov 01, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Military, Music, Sexuality, 1970s

Death and Horror

In 1977, the BBC released "Death & Horror" — an album of horror-themed sound effects which (unlike most sound-effect records) made its way onto the UK's Top 100 charts. The entire album is on YouTube, so perhaps some of you might find a use for it this Halloween.The success of the album attracted a prominent critic. As reported by the Associated Press (Mar 17, 1977):

She called the record "utterly irresponsible" and said Wednesday she will ask the government to ban it.

The publicly financed British Broadcasting Corp., a generally sedate organization known to many Britons as "Auntie BBC," said the long-playing record was intended for drama groups, owed most of its effects to "the mistreatment of large white cabbages," was made "without the loss of a single member of the staff" and assuredly was no cause for alarm. . .

Mrs. Whitehouse, who has campaigned against stage nudity and pornography such as a proposed film on the sex life of Jesus Christ, sent protests to the head of the BBC, Sir Michael Swann, and said she will complain to Home Secretary Merlyn Rees.

"What is the BBC's aim?" she asked. "To brutalize and desensitize people?"

Mary Whitehouse was a well-known "decency" campaigner. Wikipedia has a long article about her.

00:01 The Guillotine

00:10 Arm Chopped Off

00:15 Head Chopped Off

00:22 Sawing Head Off

00:31 Leg Chopped Off

00:38 Neck Twisted And Broken

00:43 Arm Broken

00:49 Stake Driven Through Heart

00:55 Branding Iron On Flesh

01:08 Red Hot Poker Into Eye

01:18 Nails Hammered Into Flesh

01:40 The Scaffold (Trap Opens, Body Falls)

01:50 Sawing Leg Off

02:08 The Firing Squad (Commands And Volley)

02:35 Whipping

03:15 Three Gun Shots

03:27 Burning At The Stake

04:00 Dagger Thrown Into Wood

04:08 Arrows Fired Into Wood

04:20 The Pendulum

Monsters And Animals

04:55 The Mad Gorilla

06:05 Monsters Roaring

06:36 Wolf Howling

06:58 Werewolves Howling

07:22 Wolves Baying At The Moon

08:00 Wolves Howling And Snarling

08:48 The Hell-Hound (Growling And Snarling)

09:28 The Hell-Hound (Panting)

09:48 Bats Calling

10:24 Bats Squeaking And Flying

11:00 Dracula In Flight

11:55 Snake Hissing

12:40 Rattlesnake

12:58 A Cat Howl

Creaking Doors And Grave Digging

13:10 Creaky Door Closes

13:19 Creaky Door Opens

13:28 Creaky Door Closes

13:40 Heavy Creaky Door Opens

13:49 Coffin Lid Closes

13:59 Nailing Coffin Lid Down

14:31 Coffin Lid Opening

14:47 Assorted Creepy Creaks

15:30 Crypt Door Closing

15:45 Grave Digging (In Stoney Ground)

16:36 Grave Digging (In Wet Ground)

17:25 Portcullis Closing

17:38 Phantom Of The Opera (Organ Sounds)

18:44 Ghostly Piano Sound (Low Pitch)

19:01 Ghostly Piano Sound (Low Pitch)

19:23 Ghostly Piano Sound (Low Pitch)

19:40 Ghostly Piano Sound (High Pitch)

19:51 Ghostly Piano Sound (High Pitch)

20:10 Ghostly Piano Sound (High Pitch)

20:22 The Lost Chord

22:05 A Gong Roll

21:22 Gong Struck Once

21:45 Ghostly Footsteps (With Chains)

22:40 Squelching Footsteps

Vocal Effects And Heartbeats

23:21 Strangulation (Male)

23:35 One Scream (Male)

23:43 Two Screams (Male)

24:00 Three Men Screaming

24:10 Heavy Breathing (Male)

24:45 Two Screams (Female)

24:59 Three Screams (Female)

25:15 One Long Scream (Female)

25:30 Two Women Screaming

25:44 One Woman Sobbing

26:23 Heavy Breathing (Female)

26:55 Lunatics Laughing

27:44 Human Heartbeats

28:25 Electronic Heartbeats

28:57 Frankenstein's Heartbeats

Weather, Atmospheres And Bells

29:35 Three Thunderclaps

30:15 Thunderclaps And Rain

30:54 Approaching Thunder

31:15 Rain And Distant Thunder

32:31 Heavy Rain

33:25 Eerie Wind

34:29 Weird Wind

35:23 Cathedral Bell Tolling

35:52 Church Bell Tolling

36:28 Church Bell Tolling In The Wind

37:15 Wind Howling In Ship's Rigging

38:02 Jungle At Night

38:43 Tropical Atmosphere At Night

39:23 The Electronic Swamp

40:44 Dr. Jekyll's Lab

41:23 Midnight In The Graveyard

43:30 Daytime In The Graveyard

44:35 The Chinese Water Torture

45:39 Boiling Oil

Posted By: Alex - Fri Oct 29, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Horror, 1970s, Halloween, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

Peter Puck

Peter's Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Oct 29, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Anthropomorphism, Sports, Cartoons, 1970s

The Houndcats

A series so obscure (only 13 episodes) that not even Wikipedia knows of it.Their IMDB page reveals:

The Houndcats were five crack agents--leader Stutz, strongman Muscle Mutt, master of disguise Puddy Puss, electronics whiz Rhubarb and daredevil Dingdong--who received instructions of their latest mission via exploding tape-recordings and used their specialties to foil evil. If this sounds a bit like "Mission: Impossible", it's no coincidence. Sparkplug was the name of their car which took them to their assignments.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Oct 24, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Ineptness, Crudity, Talentlessness, Kitsch, and Bad Art, Cartoons, Cats, 1970s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |