1970s

Captain Sticky

By the age of 28, Richard Pesta had become independently wealthy thanks to a lucrative fiberglass and foam business. So he decided to fulfill his dream of being a superhero, and in 1973 he turned himself into Captain Sticky, "Supreme Commander in Chief of the World Organization Against Evil". The name referred to his fondness for peanut butter.He drove around Orange County in his Stickymobile looking for crime, outfitted with a peanut butter gun and "peanut butter grenades" made of peanut butter, vinegar and alka seltzer.

He also became a fixture at San Diego Comic Con, and was constantly trying to get Marvel to make a comic book about him, but this never happened.

Apparently his superhero act wasn't entirely just a way to get attention. He used his influence to advocate for various causes such as improving nursing homes and preventing rental-car ripoffs.

He died in 2003 at the age of 57.

More info: Heroes in the Night, News From Me, Real Life Superheroes Archive

Captain Sticky with Stan Lee at San Diego Comic Con, 1975

The video below is in German, but it has some good footage of Captain Sticky in action.

Posted By: Alex - Tue May 25, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Comics, 1970s, Courage, Bravery, Heroism and Valor

Candy as a drug deterrent

1979: James Mack, a candy manufacturer representative, told government officials that banning candy sales from schools could lead to "injury, drug abuse and drinking." His reasoning was that candy provided children with an "island of pleasure," and if denied this they might seek out worse things such as drugs. They might even "leave the school premises [to seek out candy] and encounter traffic hazards".

Wisconsin State Journal - Jan 31, 1979

Posted By: Alex - Sat May 22, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Candy, 1970s

Help…It’s the Hair Bear Bunch!

The Wikipedia page.According to author Christopher P. Lehman, Hanna-Barbera "dress[ed] the bears in counterculture apparel" in order to stay on track with the "mainstream" fashion in the United States.

Posted By: Paul - Sat May 22, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Anthropomorphism, Ineptness, Crudity, Talentlessness, Kitsch, and Bad Art, Television, Cartoons, 1970s

Art-Necko Ties

Minnesota artist Mark Larson debuted his line of Art-Necko ties in 1978. These were plastic, see-through ties, and the gimmick was that he filled them with various stuff.

source: flickr

As described in the Minneapolis Star Tribune (Nov 26, 1978):

The neon tie, however, is the current front-runner. Larson's favorite, it's a stunning red-and-blue creation that makes a glowing statement about the wearer—providing he's hooked up to a power source.

And these have nothing on the proposed ties. There could be—well, the world's loudest tie (armed with a tiny loudspeaker to broadcast jets taking off); the horror movie or Vincent Price model (containing dry ice, with tiny holes in the front to permit the wearer to trail wisps of fog); the Fit-to-be-Tied Tie (a self-inflating strait-jacket that takes over when you feel you are losing control), and the chow mein tie, inspired by the Seal-a-Meal machine that is basic to the Art-Necko process.

The cowboy tie

People magazine (Jan 15, 1979) listed a few more:

Fishing Tackle features Goldfish crackers, a hook, sinker and a rubber worm. Vanity contains false eyelashes and phony fingernails. And for the ghoulish, there's Bones—scrubbed and boiled shortribs.

At the time the Art-Necko ties sold for $10. I found one for sale on eBay for $14.66. So not much increase in value in the past 40 years.

Posted By: Alex - Thu May 20, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Art, Fashion, 1970s

Eviction caused bad breath, dandruff

1979: After being evicted from the townhouse he was renting, R.L. Ussery filed a lawsuit against his former landlord seeking $11,000 in compensation. Ussery claimed that the eviction had caused him and his family to suffer from "colds, nausea, upset stomach, diarrhea dysentery, loss of hair, sweating palms, the need to void, the inability to void, nightmares, insomnia, dandruff, bad breath, dirty fingernails, odoriferous body odors, especially of the feet, palm itching, the blues and the blahs, nervousness, dry heaves and crying spells."I don't know what the result of the lawsuit was, but I think it's highly unlikely that Ussery won.

Tampa Tribune - Aug 24, 1979

Posted By: Alex - Mon May 17, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Lawsuits, 1970s

Octopus found in Restroom

The Equinox Bar, on the 22nd floor of the Hyatt-Regency, was the only revolving restaurant/bar in San Francisco, until it closed in 2007.In April 1978, a large octopus was found in the women's restroom of the bar. I haven't found any follow-ups to this story explaining why someone left an octopus there.

So the incident remains a mystery, just like the porpoise found in the men's restroom of Glasgow Central Station in 1965.

Napa Valley Register - Apr 22, 1978

Posted By: Alex - Wed May 12, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Bathrooms, Fish, 1970s

Cultural Revolution Ballet

Posted By: Paul - Wed May 12, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Dictators, Tyrants and Other Harsh Rulers, Political Correctness, Politics, 1970s, Asia

The Hudson Brothers: “Disco Queen”

Their Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sat May 01, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Fads, Ineptness, Crudity, Talentlessness, Kitsch, and Bad Art, Music, Television, 1970s, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

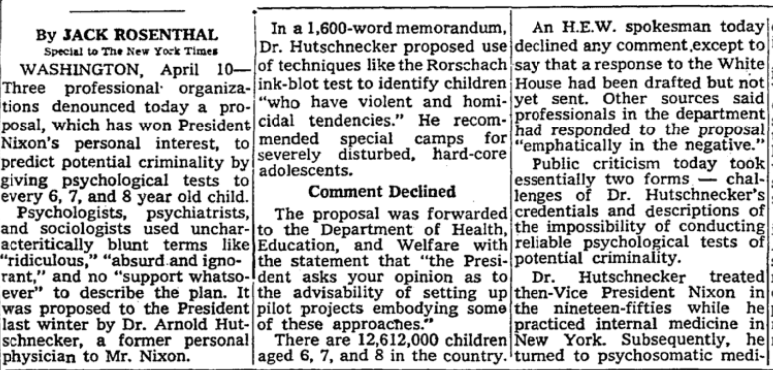

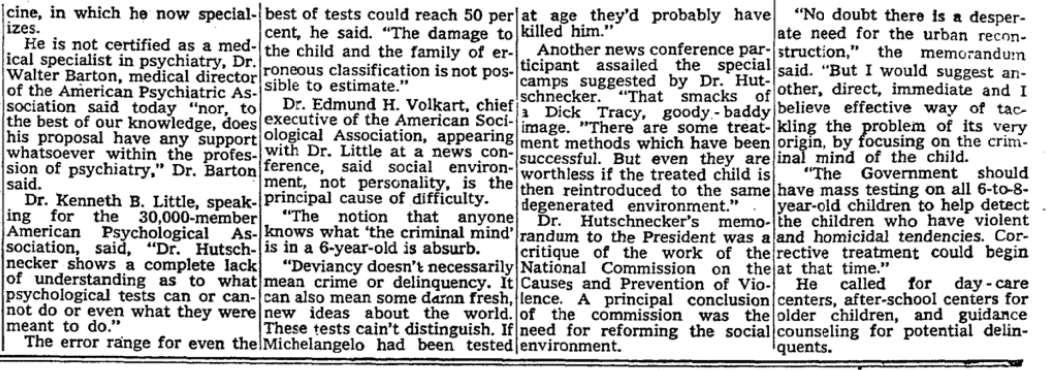

Arnold Hutschnecker’s Juvenile Criminality Tests

His Wikipedia page is here.Not mentioned is the legal charge at age 89 of seducing a patient.

Interesting details of his relationship with Richard Nixon in this obit.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Apr 24, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Crime, Psychology, Children, 1970s

Elephant Bells

A creation of the 1970s. The next level beyond bell-bottoms.

Tampa Bay Times - Oct 15, 1972

Posted By: Alex - Mon Apr 19, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Fashion, 1970s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |