Advertising

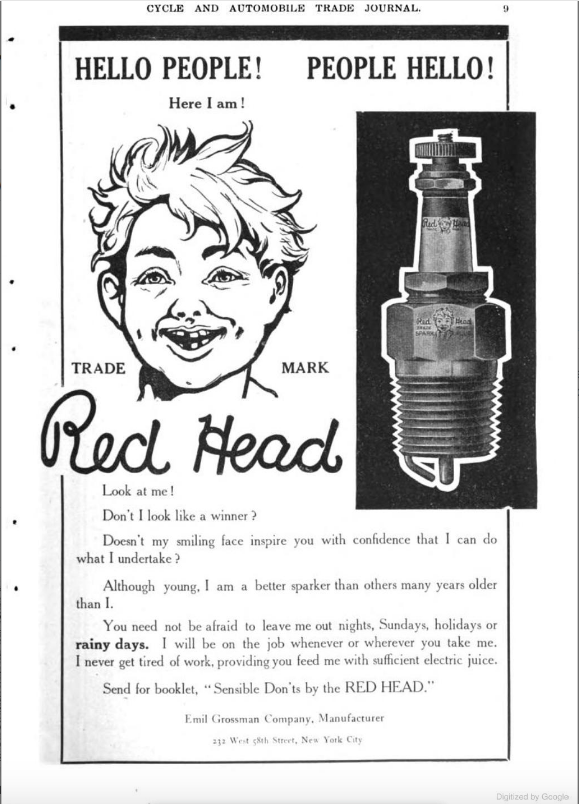

Follies of the Madmen #514

A face to inspire confidence?The source.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Aug 30, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Business, Advertising, Intelligence, Motor Vehicles, 1900s

The Ballad of a Gentle Laxative

These 1987 TV ads for Doxidan laxative, featuring the 'Doxidan Cowboy,' seem to inspire both love and hate. A lot of people on YouTube remember them fondly, but in newspapers from the time they were often cited as being among the most annoying commercials on TV.The singer was Skeeter Starke. He has a YouTube channel.

Fort Myers News-Press - Jan 25, 1987

via History's Dumpster

Posted By: Alex - Thu Aug 26, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Music, Advertising, Excrement, 1980s

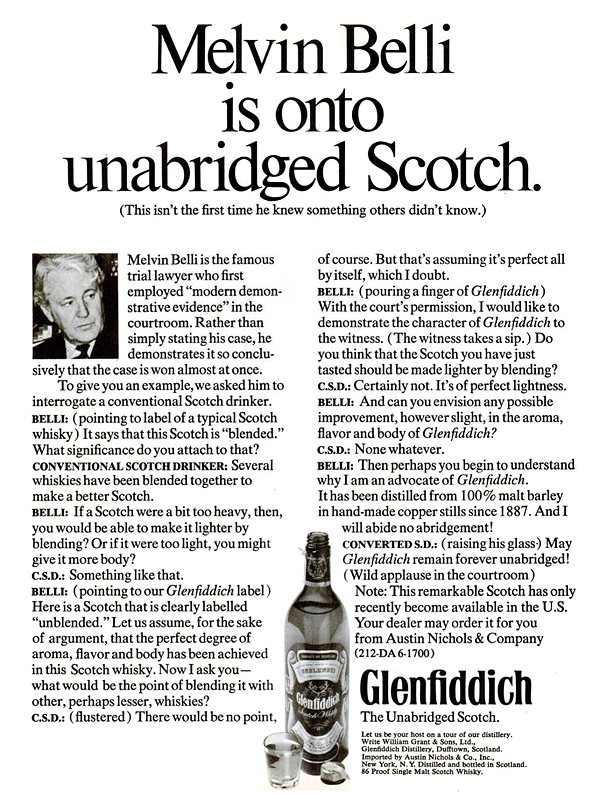

Melvin Belli Drinks Glenfiddich

The ad below, in which trial lawyer Melvin Belli endorsed Glenfiddich scotch, ran in the New York Times and New York Magazine in early 1970. Taken at face value, it doesn't seem like a particularly noteworthy ad. However, it occupies a curious place in legal history.Before the 1970s, it was illegal for lawyers to advertise their services. So when Belli appeared in this ad, the California State Bar decided he had run afoul of this law — even though he hadn't directly advertised his services. It suspended his license for a year. The California Supreme Court later lowered this to a 30-day suspension — but it didn't dismiss the punishment entirely.

Some high-placed judges felt sympathetic to Belli, which added fuel to the movement to end the 'no advertising' law for lawyers, and by 1977, the Supreme Court had struck down the ban on advertising, saying that it violated the First Amendment. That's why ads for legal services now appear all over the place. Compared to the ads one sees nowadays, Belli's scotch endorsement really seems like no big deal at all.

More info: Belli v. State Bar, "Remember when lawyers couldn't advertise?"

New York Magazine - Mar 2, 1970

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 16, 2021 -

Comments (5)

Category: Law, Advertising, 1970s

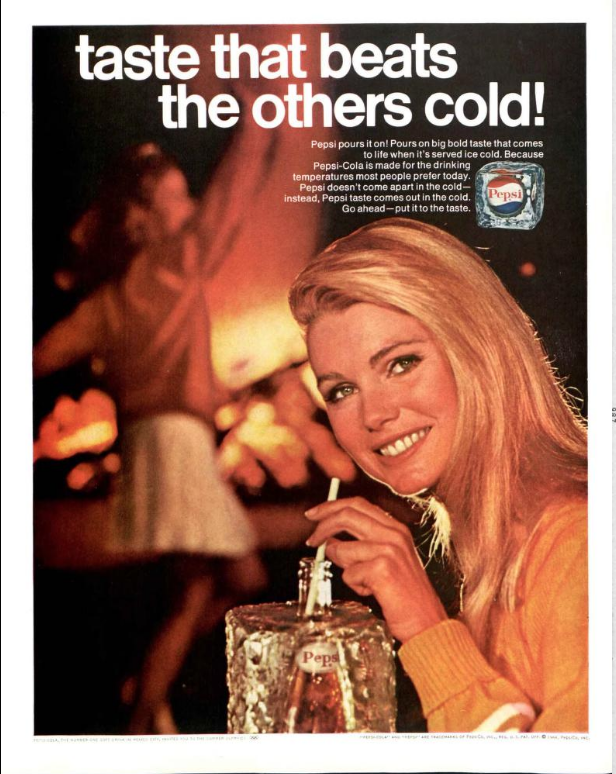

Follies of the Madmen #513

What size of empty container was used to make that ice cylinder for the Pepsi bottle, and what size freezer could accommodate it? Only commercial units. How many hours would you have to prolong your sipping, to justify the creation of that ridiculous amount of ice for cooling one bottle of Pepsi? And was this gal the only one at the bonfire to receive such a treat? So many questions...

Posted By: Paul - Sun Aug 15, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Business, Advertising, Excess, Overkill, Hyperbole and Too Much Is Not Enough, Soda, Pop, Soft Drinks and other Non-Alcoholic Beverages, 1960s

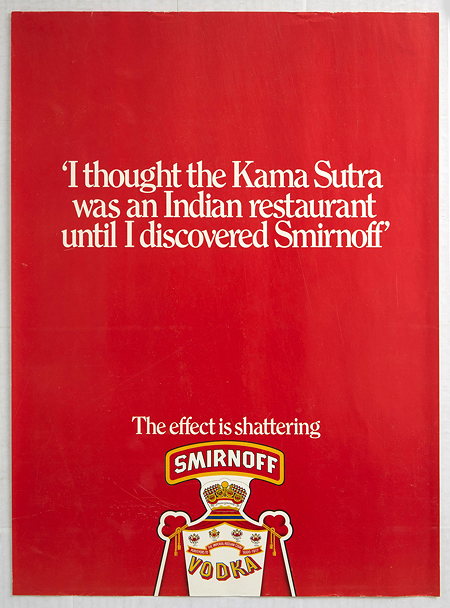

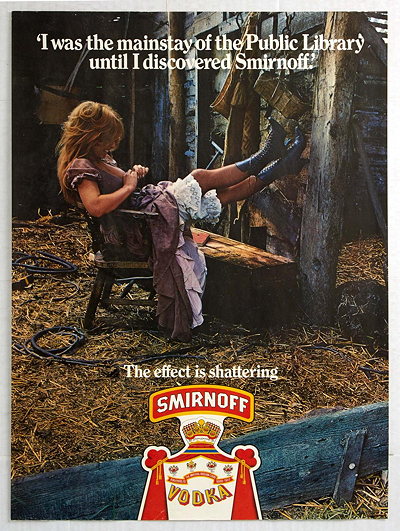

“I thought the Kama Sutra was an Indian restaurant”

Smirnoff ran this ad in the 70s but reportedly pulled it after a few months when its market researchers surveyed customers and discovered that "60 per cent of them thought that the Kama Sutra was indeed an Indian restaurant."

image source: codex

But according to Delia Chiaro in The Language of Jokes, the ad lived on in popular memory, inspiring a genre of "Smirnoff jokes".

I thought innuendo was an Italian suppository until I discovered Smirnoff.

I thought cirrhosis was a type of cloud until I discovered Smirnoff.

However it was not long before the graffitists began to abandon the formula, first by substituting the word Smirnoff with other items:

I thought Nausea was a novel by Jean-Paul Sartre until I discovered Scrumpy.

Soon, the caption began to move more radically away from the matrix, as more items were changed. In the next example there is no allusion to drink whatsoever:

I used to think I was an atheist until I discovered I was God.

Although Smirnoff jokes are now practically obsolete, the I thought A was B until I discovered C formula has now frozen into the English language as a semi-idiom. Today we can find graffiti (or indeed hear asides) such as:

I used to talk in cliches but now I avoid them like the plague

in which the original matrix is barely recognizable.

Below is another Smirnoff ad from the same series.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 11, 2021 -

Comments (5)

Category: Inebriation and Intoxicants, Advertising, 1970s, Jokes

Raisin Bran keeps you regular

Trapeze artists discussing bowel movements doesn't conjure up good images.

Lincoln Star - Apr 1, 1938

Possibly relevant, this Snopes article: Did a Trapeze Artist with Diarrhea Defecate on 23 People? (The answer is no)

Posted By: Alex - Thu Aug 05, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Advertising, Cereal, Excrement, 1930s

Ron Popeil, RIP

His obit at CNN.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Jul 30, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Excess, Overkill, Hyperbole and Too Much Is Not Enough, Inventions, Chindogu, Television, Advertising

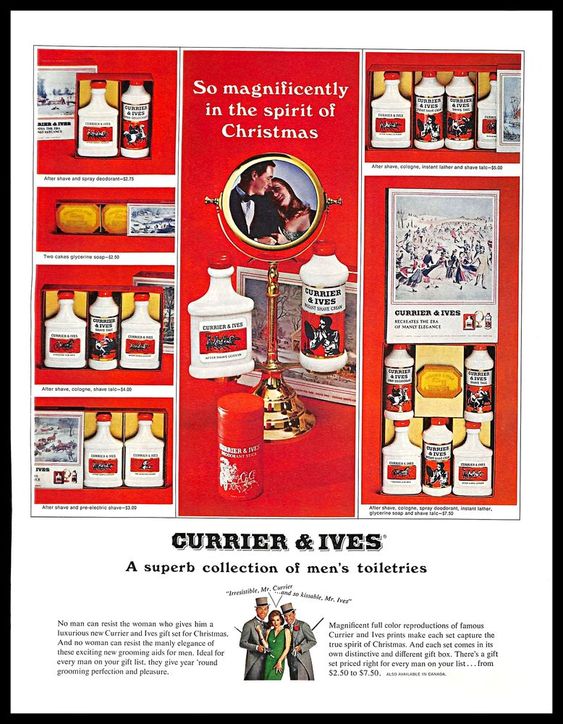

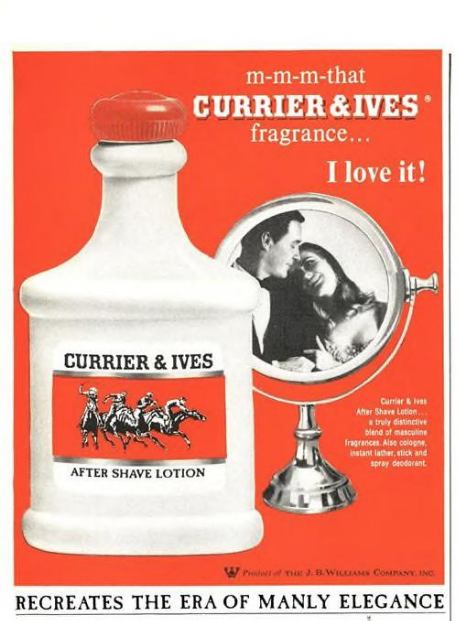

Currier and Ives Toiletries

Many cultural touchstones of my youth have vanished, and mean nothing now to new generations."Currier and Ives" is one such.

At one time this name meant "nostalgic popular culture invocations of the nineteenth century." But given that meaning, what kind of smells would you necessarily associate with it? Horse manure? Coal fires? Unwashed longjohns? Was that what was meant by "manly elegance?

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jul 29, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Advertising, 1960s, Perfume and Cologne and Other Scents, Nostalgia

Presenting the Losers

A 1967 ad campaign for Eastern Airlines.Of course, I'm pretty sure all the women in the ad were actually models/actresses. So in their true profession they were winners of a spot in the campaign. Most notably, that's Ali MacGraw sitting in the front row.

Time - Sep 29, 1967

Some analysis by Kathleen Barry in Femininity in Flight: A History of Flight Attendants —

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jul 26, 2021 -

Comments (5)

Category: Advertising, Air Travel and Airlines, 1960s

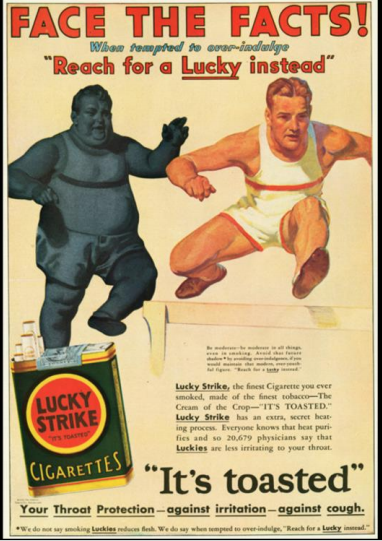

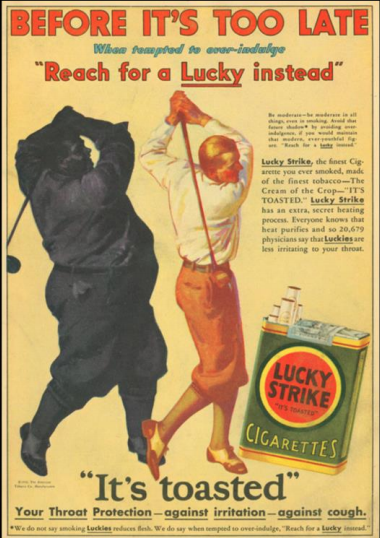

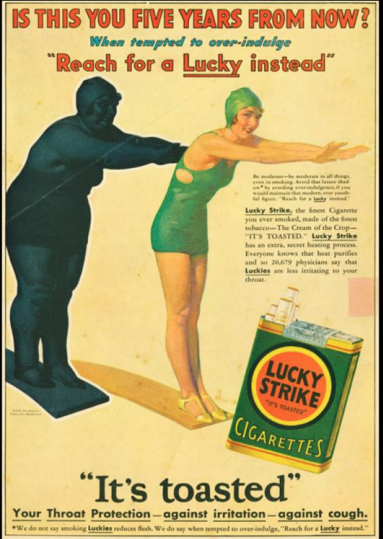

Lucky Strikes as Weight-Loss Aid

See more in this series at the link.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jul 26, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Advertising, Smoking and Tobacco, Twentieth Century, Dieting and Weight Loss

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |