Ancient Times

The Statue of Theagenes

Some weirdness from Ancient Greece, 5th century BCE. As told by Chris Gosden in Magic a History: From Alchemy to Witchcraft, from the Ice Age to the Present (2020).More info: wikipedia, perseus.tufts.edu

The story reminds me of the guy in Arizona, in the 1980s, who decided to shoot a 27-foot saguaro cactus, but the cactus then fell on him and killed him. Clearly, sometimes inanimate objects fight back.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Feb 21, 2025 -

Comments (1)

Category: Death, Statues and Monuments, Ancient Times

Unusual Punishments of the Theodosian Code

In 429 AD the Roman emperor Theodosius II established a commission to write down all the laws of the Roman Empire since 312, covering all the Christian emperors. The resulting work was the Codex Theodosianus (or Theodisian Code).In his book The Triumph of Christianity, biblical scholar Bart Ehrman lists some of the more unusual punishments included in the codex:

- Imperial bureaucrats who accepted bribes were to have their hands cut off (Theodosian Code l.16.7)

- ineffective guardians of girls who had been seduced were to have molten lead poured down their throats (Theodosian Code 9.24.1)

- tax collectors who treated women tax delinquents rudely were to "be done to death with exquisite tortures"

- anyone who served as an informer was to be strangled and " the tongue of envy cut off from its roots and plucked out" (Theodosian Code 10.10.2)

- slaves who informed on their masters were to be crucified (Theodosian Code 9.5.1.1)

- anyone guilty of parricide "shall not be subjected to the sword or to fire or to any other customary penalty, but he shall be sewed in a leather sack, and, confined within its deadly closeness, he shall share the companionship of serpents" and then thrown into a river or ocean "so that while still alive he may begin to lose the enjoyment of all the elements" (Theodosian Code 9.15.1)

Posted By: Alex - Fri Dec 13, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Law, Ancient Times

Sortes Vergilianae

Ever since ancient times, it's been widely believed that it's possible to use the text of Vergil's Aeneid to foretell the future. The practice is called the sortes Vergilianae.What you do: think of a question about future events in your life, then open the Aeneid to a random page. The first passage that catches your eye will provide the answer to your question.

Of course, the practice is little known today. Instead, we've got the Magic 8 Ball. Someone should make a version of the Magic 8 Ball that would offer up lines from Vergil.

More details from A History of Reading by Alberto Manguel:

Posted By: Alex - Wed Nov 27, 2024 -

Comments (6)

Category: Predictions, Ancient Times

Corn Rocks

"Corn rocks" are pieces of lava rock that have impressions of pieces of corn imbedded in them. Geologists have found many samples of corn rocks around the Sunset Crater Volcano in northern Arizona. When the volcano erupted, about 1000 years ago, the people that lived around it were evidently putting pieces of corn in the lava to create these rocks. Why they did this is anyone's guess. Perhaps for religious reasons, or perhaps just for fun.

Source: Google Arts & Culture

Geologists tried to create corn rocks of their own at Kilauea Volcano in Hawaii, but they found it wasn't as straightforward as they had assumed. Putting the corn in the path of a lava flow didn't work. Nor did dropping corn on top of a flow. Geologist Wendell Duffield tells the rest of the story:

Obviously, it would not be safe for humans to carry ears of corn into the fallout zone of a towering lava fountain. A safe setting, however, would be at what geologists call an hornito (means "little oven" in Spanish). An hornito is essentially a miniature volcano that spews molten blobs of melt that fall back to Earth and accumulate into a welded-together chimney-like stack as they solidify and cool...

So, early Native Americans living near the present site of Sunset Crater Volcano witnessed an eruption that at some stage could be safely approached to place ears of corn at the base of an active hornito.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Aug 11, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Nature, Science, Anthropology, Ancient Times, Arizona

Letter to Diognetus

The "Letter to Diognetus" is an obscure early Christian text, probably written in the second century AD. Its author is unknown.No known references to this letter survive from ancient times. The only reason scholars are aware of it today is that a copy of it was discovered in 1436 — and it's the way it was discovered that was unusual. A young cleric was at a fishmarket and realized that the paper the fishmonger was wrapping the fish in seemed to be from an ancient manuscript. He rescued the paper and discovered this previously unknown ancient text written on it.

From "An Introduction to the Letter to Diognetus," by William Varner:

More info: wikipedia

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jul 16, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Lost, Newly Discovered, Cutting-Room-Floor, and Discarded Cultural Items, Ancient Times

Crepitus, the God of Flatulence

Crepitus was allegedly the Roman god of flatulence. He was usually depicted as a young child farting.However, he's only allegedly so because there's controversy about whether the Romans recognized such a god, or whether Crepitus was the creation of early Christians trying to satirize pagan beliefs. According to Wikipedia, there are references to Crepitus in ancient texts, but only in Christian works, not pagan ones.

image source: POOP Project

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jun 08, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Religion, Flatulence, Ancient Times

Twitch Divination

Twitch divination (also known as palmomancy) was the ancient art of divining the future by interpreting body tremors, tics, and twitches.According to the Faces and Voices blog, few manuals of palmomancy survive from ancient times. But the few that do offer some interesting advice. For instance, from a treatise preserved at Manchester's John Rylands Library:

And what does it mean if your buttock twitches? The answer from Omens and Oracles: Divination in Ancient Greece by Matthew Dillon:

Melampous' Twitchings covers some 187 cases. Involuntary twitchings of the body were easily interpreted as ominous by those who experienced them, and this handy guidebook provided instant advice to the reader as to their meaning... Dating to the third century AD, the earliest papyrus begins with the entry:

[A twitching of] the left buttock means joy: for the slave, something beneficial; for the virgin, blame will fall on the widow for strife [this is somewhat difficult to understand; there may be an allusion here the reader would have recognised]; for the soldier, promotion.

This is in fact a more elaborate version of two short entries in Melampous' Twitchings, which indicate that twitching of either buttock means prosperity.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jun 04, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Predictions, Ancient Times

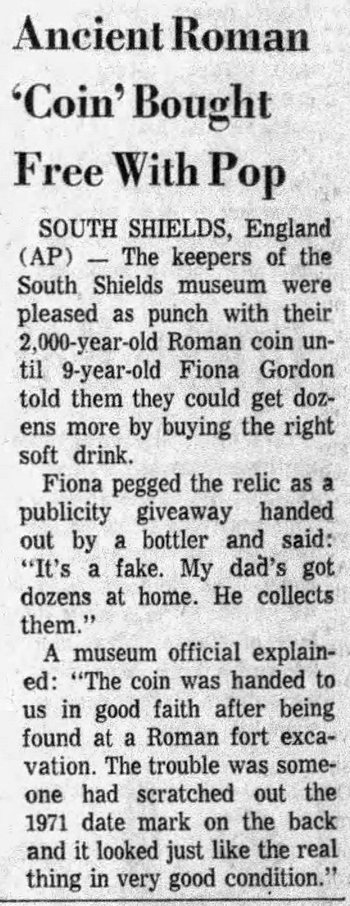

The replica Roman coin that fooled a museum

Nov 1971: Nine-year-old Fiona Gordon realized that the supposedly ancient Roman coin on display at the South Shields Museum was actually a promotional replica given away by a soft drinks company, Robinsons.

Newport News Daily Press - Nov 3, 1971

I'm pretty sure that the coin below is similar (if not identical) to the one that was on display at the museum. In 1971, Robinsons sent these coins to anyone who mailed in enough bottle caps. (Source: CoinCommunity.com)

Posted By: Alex - Tue Feb 22, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Imitations, Forgeries, Rip-offs and Faux, Money, Soda, Pop, Soft Drinks and other Non-Alcoholic Beverages, 1970s, Ancient Times

Self-castration in early Christianity

Some ancient weirdness: The First Council of Nicaea, in 325 AD, was a meeting of Christian bishops in which they tried to establish the rules and doctrines that all Christians were supposed to follow. Wikipedia says:However, one of the lesser-known rules that the bishops enacted at the Council was to ban men who had castrated themselves from being in the clergy. Because, apparently, self-castration had become something of a fad among early Christians. Enough so that the bishops felt the need to put an official stop to the practice.

The historian Daniel Caner has examined this issue in his 1997 article "The practice and prohibition of self-castration in early Christianity".

Caner notes that the fad had its origin in a passage from the New Testament, Matthew 19:12, in which Jesus appears to endorse the practice of self-castration. As the passage reads in the King James translation:

Most interpreters of the Bible, ancient and modern, argue that when Jesus used the word 'eunuch' he meant it as a synonym for 'celibacy'. Apparently this was a common use of the term 'eunuch' in the ancient world.

Nevertheless, he used the term eunuch. So some early Christians decided the passage should be taken literally. In which case, Jesus seemed to be saying that, while self-castration was not appropriate for all men, for an elite few it was an ideal to strive for. Inspired by this passage, a number of men "took the sickle and cut off [their] private parts."

The most prominent Church father who was said to have castrated himself was Origen of Alexandria (c. 185 - c. 253). But Caner notes that there was an entire sect of early Christians, the Valesians, who embraced the practice. Wikipedia says that, in addition to castrating themselves, "They were notorious for forcibly castrating travelers whom they encountered and guests who visited them."

According to Caner, the more widely adopted Christianity became in the Roman empire, the more the Church tried to present itself as the upholder of mainstream values, and self-castration really didn't fit into that image. Therefore, "Radical manifestations of an ideal de-sexualization... became a 'heretical' threat to the orthodox community."

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jul 02, 2021 -

Comments (5)

Category: Body Modifications, Fads, Religion, Ancient Times, Genitals

Shepherd of the Royal Anus

Strange job title. 'Shepherd of the Royal Anus' (neru pehut) was a title held by several court physicians in Ancient Egypt, including Ir-en-akhty (who lived during the First Intermediate Period) and his predecessor Khuy. It could also be translated as 'Herdsman of the Anus' or 'Guardian of the Anus'. Here's a partial explanation:And more:

Posted By: Alex - Sat Sep 01, 2012 -

Comments (6)

Category: Medicine, Odd Names, Ancient Times

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |