Animals

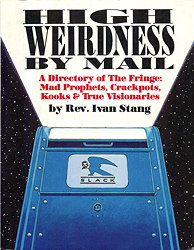

Follies of the Madmen #472

That mouse is definitely giving the finger. Is it supposed to be a sexy lure for male mice to entice them into the trap? I'm confused....

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Apr 10, 2020 -

Comments (8)

Category: Animals, Anthropomorphism, Antisocial Activities, Business, Advertising, Death, 1960s

Do Beavers Rule on Mars?

In the May 1930 issue of Popular Science magazine, Thomas Elway advanced the unusual hypothesis that Mars was inhabited by a race of beavers. His idea was subsequently reported in many newspapers.As far as I can tell, Elway wasn't actually a scientist. He was a journalist. So perhaps one shouldn't attach too much weight to his opinion. Still, he gets points for creativity.

Semi-Weekly Spokesman Review - Oct 12, 1930

Elway's argument was based on the assumption (widespread at the time) that there was plant life on Mars. Therefore, animal life was also considered possible. His reasoning then proceeded as follows:

This lack of manlike life is precisely what a biologist would expect. Man and man's active mind are believed to be products of the Great Ice Age, for that time of stress and competition on earth is what is supposed to have turned mankind's anthropoid ancestors into men. The period of ice and cold over wide areas of the earth was caused, at least in part, by the elevation of continents and mountain ranges. On Mars, no mountain ranges exist, and it probably never had an Ice Age.

It is on these hypotheses that science bases its assumption that there is no human intelligence on Mars, and that animal life on the planet is still in the age of instinct. The thing to expect on Mars, then, is a fish life much like that on earth, the emergence of this fish life onto the land, and the evolution of these Martian land-fishes into retilelike creatures. Finally, animals resembling the earth's present rodents like rats, squirrels, and beavers would make their appearance.

The chief reason to expect this final change of Martian retiles into primitive mammals lies in the fact that on earth this evolution seems to have been forced by changeable weather. And Mars now possesses seasonal changes like those on earth.

Pure biological reasoning makes it probable, therefore, that the evolution of warm-blooded animals may have occurred on Mars much as it did here. There seems no reason to believe that Martian life has gone farther than that. Mars is a relatively changeless planet. Biologists suppose that the rise and fall of mountains, the increase and decrease in volcanic activity, and the ebb and flow of climate forced life on earth along its upward path. Martian life of recent ages seems to have lacked these natural incentives to better things.

Now, there is one creature on earth for the development of whose counterpart the supposed Martian conditions would be ideal. That animal is the beaver. It is either land-living or water-living. It has a fur coat to protect it from the 100 degrees below zero of the Martian night.

The Martian beavers, of course, would not be exactly like those on earth. That they would be furred and water-loving is probable. Their eyes might be larger than those of the earthly beaver because the sunlight is not so strong, and their bodies might be larger because of lesser Martian gravity. Competent digging tools certainly would be provided on their claws. The chests of these Martian beavers would be larger and their breathing far more active, as there is less oxygen in the air on Mars.

Such beaver-Martians are nothing more than pure speculation, but the idea is based upon the known facts that there is plenty of water on Mars; that vegetation almost certainly exists there; that Mars has no mountains and could scarcely have had an Ice Age; and that evidences of Martian life are not accompanied by signs of intelligence.

Herds of beaver-creatures are at least a more reasonable idea than the familiar fictional one of manlike Martians digging artificial water channels with vast machines or the still more fantastic notion of octopuslike Martians sufficiently intelligent to plan the conquest of the earth.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Apr 02, 2020 -

Comments (5)

Category: Aliens, Animals, Science, 1930s

Horse

Posted By: Paul - Thu Apr 02, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Body Modifications, Cartoons

Cosmic Guinea Pig

Posted By: Paul - Sat Mar 14, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Anthropomorphism, Humor, Philosophy

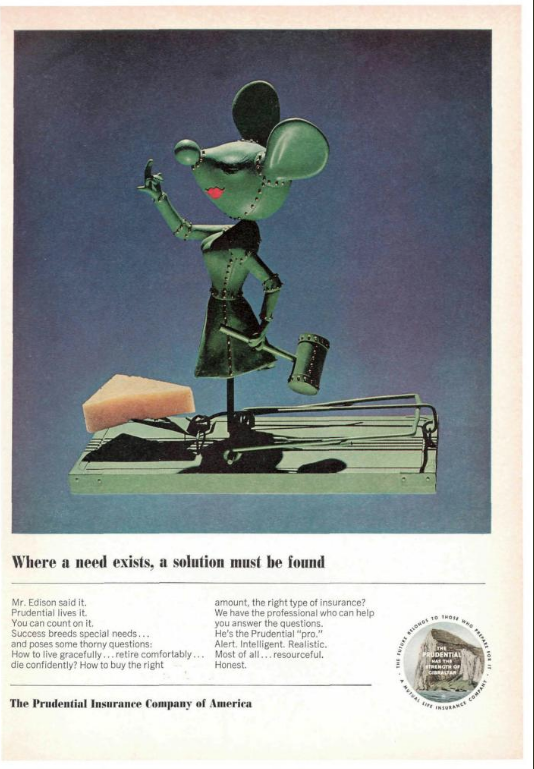

“Miss Wisconsin” Arrives for National October Cheese Week Festival, 1951

She's the one on your left.

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Mar 01, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Food, 1950s

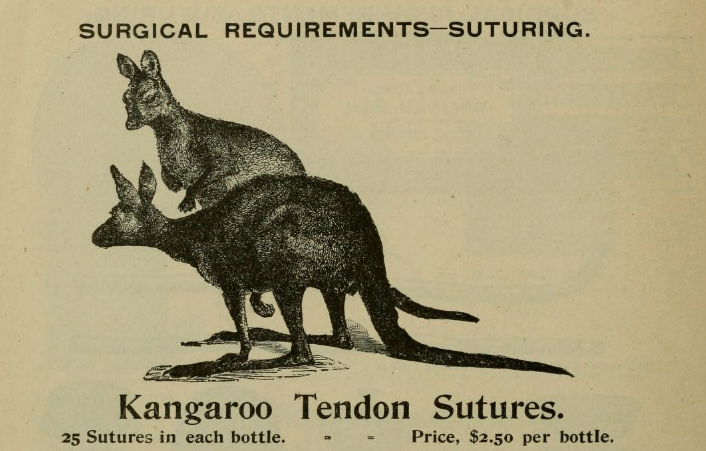

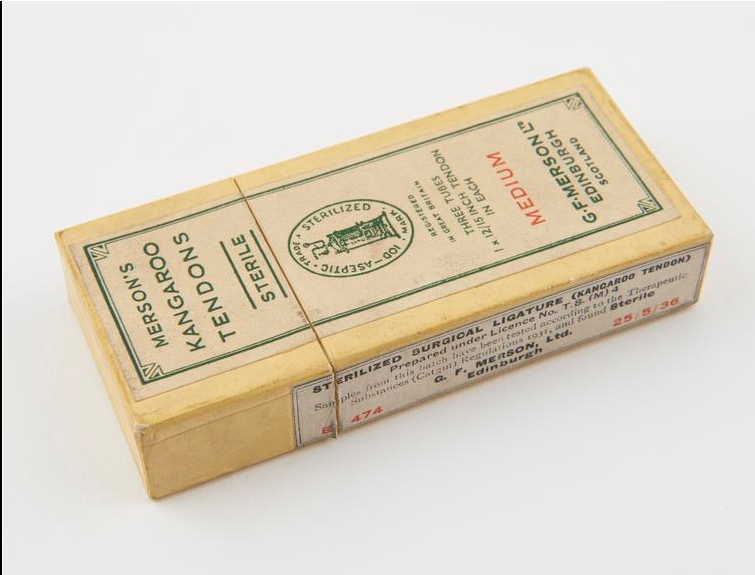

Kangaroo Tendon Sutures

Source of first two images, with further explanation.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Feb 19, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Medicine, Nineteenth Century

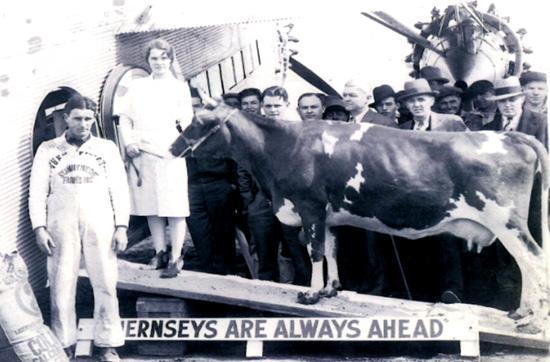

Elm Farm Ollie Day

Feb. 18 is Elm Farm Ollie Day, commemorating the first flight in a plane by a cow. An article posted over at rootsweb.ancestry.com tells us that Elm Farm Ollie (aka Sunnymede Ollie, Nellie Jay, or Sky Queen) is remembered each year at the dairy festival in Mount Horeb, Wisconsin:

A 1930 news-wire story provided details about the historic flight:

Claude M. Sterling, of Parks Air college, will pilot Sunnymede Ollie, Guernsey from Bismarck, Missouri, over the city in a tri-motored Ford.

The cow will be fed and milked and the milk parachuted down in paper containers. A quart of milk will be presented to Colonel Lindbergh when he arrives.

Weighing more than 1000 pounds, the cow will be flown to demonstrate the ability of aircraft. Scientific data will be collected on her behavior.

-The Evening Tribune (Albert Lea, Minn.) - Feb. 18, 1930.

More info at wikipedia and mustardmuseum.com.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Feb 18, 2020 -

Comments (7)

Category: Animals, Farming, Air Travel and Airlines, 1930s

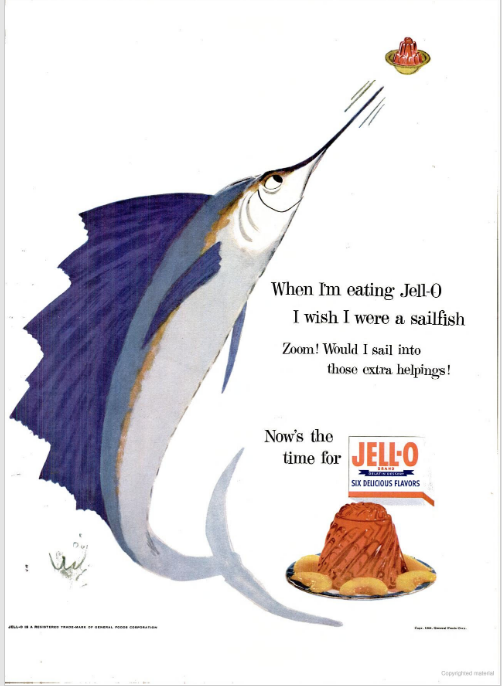

Follies of the Madmen #466

This was part of a campaign that made far-fetched comparisons between the animal kingdom and a desire to eat Jello.Source.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Feb 15, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Business, Advertising, Food, 1950s

Explosion, Assault, Ostriches

Somehow I missed this video from 2012. Theorized at the time to be a viral marketing ploy. But I can't find any evidence it was ever resolved. Can WU-vies pin down a definitive answer?

Posted By: Paul - Mon Feb 10, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Ambiguity, Uncertainty and Deliberate Obscurity, Animals, Violence, Advertising

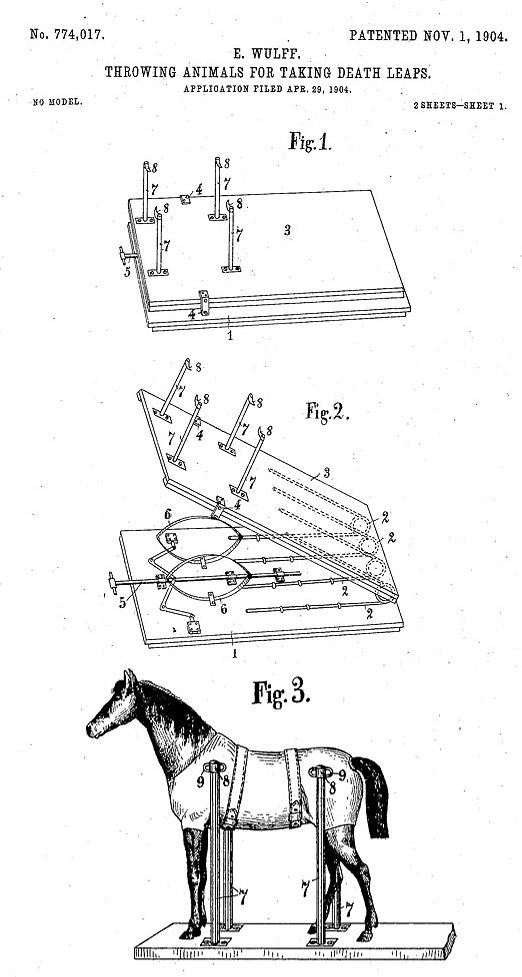

Throwing Animals for Taking Death Leaps

Circus proprietor Edward Wulff patented a curious device in 1904. It was an apparatus that catapulted animals upwards. It had the rather alarming title, "Throwing Animals For Taking Death Leaps" (Patent No. 774,017). Wulff claimed it could throw "horses, elephants, monkeys, &c.." The patent illustration shows a horse, so these were evidently the primary animal being thrown.

The device was relatively straight-forward. The animals were placed in a harness that held them on top of a spring-powered platform. The release of the springs then flung the animals upwards. Wulff emphasized that his apparatus was designed, via the harness, to place the projecting force on the full body of the animal, rather than just their legs. He seemed to feel that this was a safer, more humane method of throwing animals.

Wulff explained that this device was designed to be used as part of a circus stunt known as "a death leap or so-called 'salto-mortale.'" But he didn't offer any further explanation about the nature of the stunt or how far the animals were flung. And I couldn't locate any descriptions of this stunt in other sources. All the references to a 'death leap' stunt that I came across involved human trapeze artists, not animals. So I was about to conclude that the stunt would have to remain a mystery until I got the idea to check if Wulff had filed the patent in any other countries. Sure enough, there was a British version of the patent, and while its text was almost identical, it had a different title that explained the nature of the stunt:

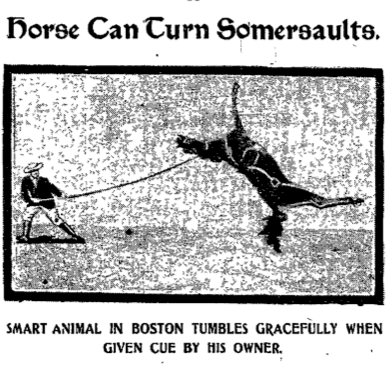

So Wullf's apparatus was evidently designed to somersault animals. Not simply to catapult them upwards. This made me recall something I posted here on WU back in 2012. It was a brief item that appeared on the front page of the Washington Post's 'Miscellany Section' on April 21, 1907, titled 'Horse Can Turn Somersaults.' At the time, this random reference to a somersaulting horse totally baffled me. I even suspected it was a hoax. But now it makes sense. It must have been a circus stunt. Perhaps it even made use of Wulff's invention. I can't find any evidence that Wulff's circus was in Boston in April 1907, but it was in New York in December of that year.

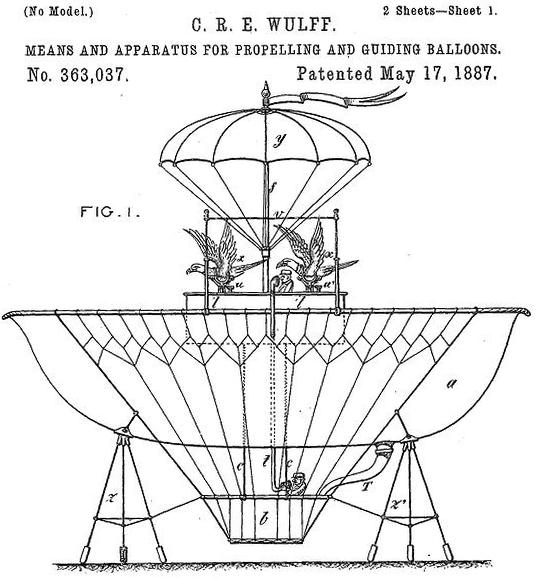

Wulff, it turns out, was the author of another odd patent, granted to him in 1887. The patent was titled, "Means and apparatus for propelling and guiding balloons." He intended to use birds such as "eagles, vultures, condors, &c" to guide balloons. The birds would be attached to the balloon by a harness, and an aeronaut would then force them to fly in the desired direction, thereby propelling the balloon.

This patent has received quite a bit of attention, because there's a lot of interest in the history of early attempts at flying machines. Knowing that Wulff was a circus proprietor, I wonder if he intended his eagle-guided balloon to be used as part of a circus act, rather than as a practical flying machine.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Feb 09, 2020 -

Comments (6)

Category: Animals, Inventions, Patents, ShowBiz, 1900s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |