Animals

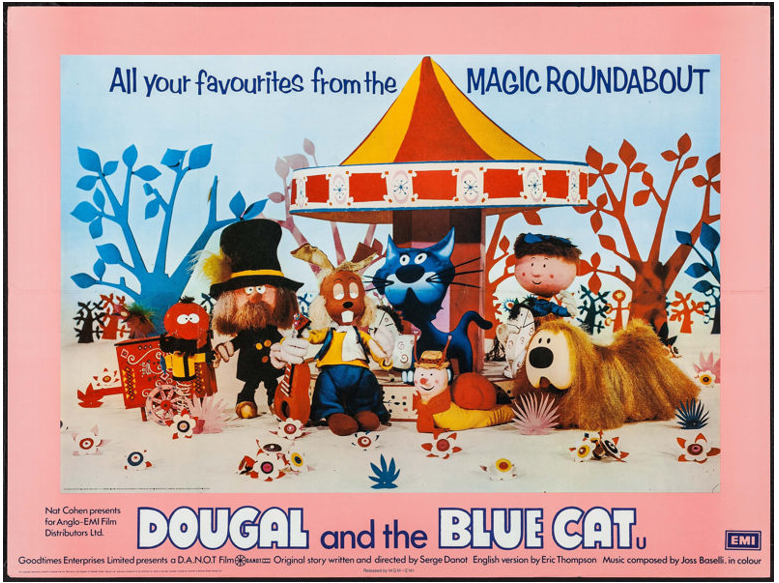

Dougal and the Blue Cat

Everything was extra trippy in the 1970s.The Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jun 18, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Animals, Anthropomorphism, Fey, Twee, Whimsical, Naive and Sadsack, Music, Fantasy, Stop-motion Animation, Psychedelic, 1970s

Hen Hop

Hen Hop, Norman McLaren,

We've featured the work of Norman McLaren before on WU, but never this one, I think.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jun 06, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Cartoons, 1940s, Dance

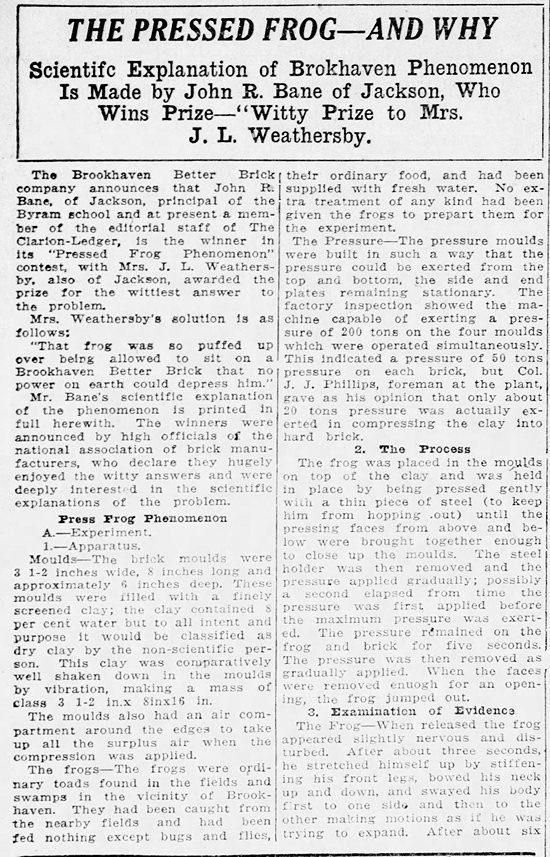

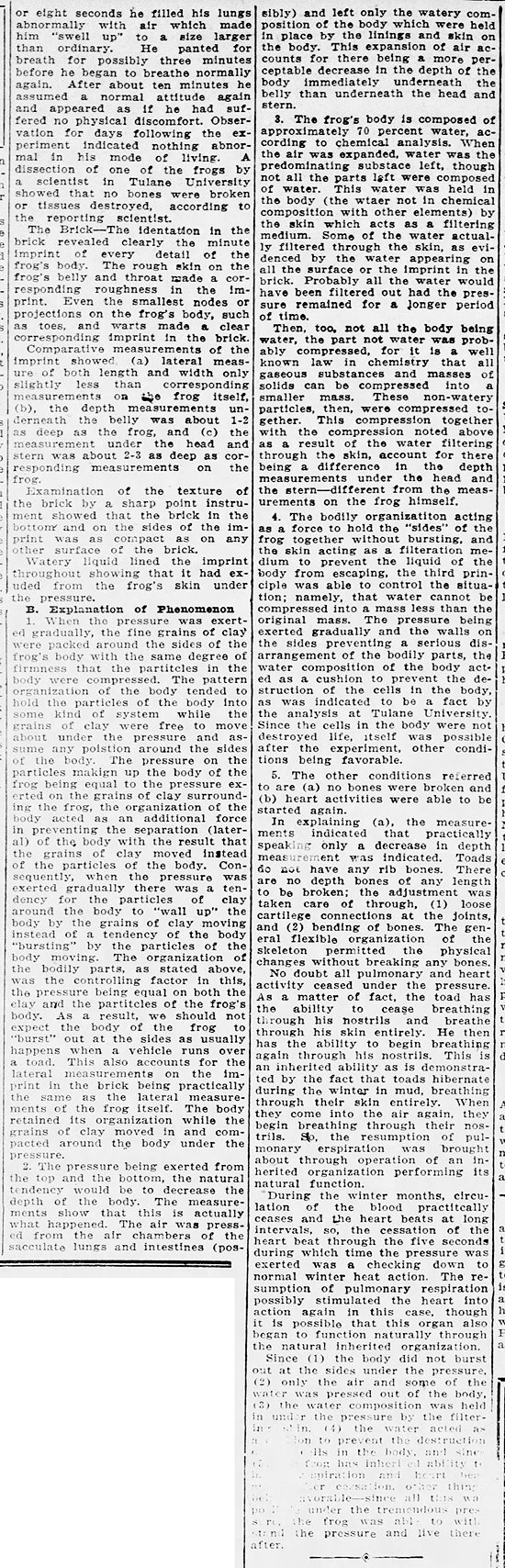

The Pressed Frog Phenomenon

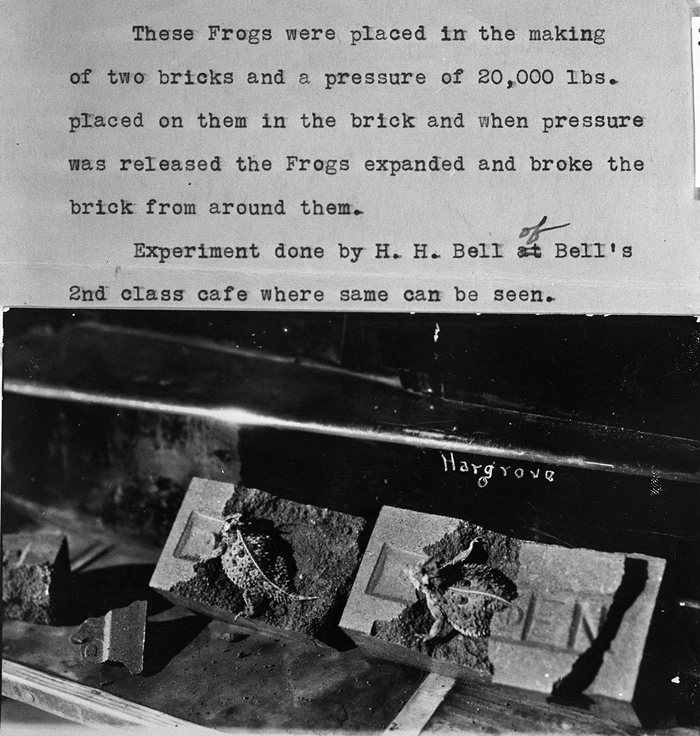

I found the image below at the Texas History site of the University of North Texas. It appears there as is, without any further explanation (or date).

I realize that the indentations on top of bricks are called 'frogs', but why were actual frogs being placed inside bricks?

As far as I can tell, it must have been an experimental demonstration of the 'pressed frog phenomenon' — this phenomenon being that one can place a living frog inside a brick as its being made, apply thousands of pounds of pressure to the brick to mold it, and the frog will survive. The frog won't be happy about the experience, but it won't burst. Whereas the same pressure applied to a frog that isn't in a brick will definitely cause it to burst.

Obviously the brick hasn't been heated in a kiln, because that would definitely cook the frog.

The article below from 1925 explains the science of why a frog in a brick doesn't burst. The key part of the (overly long) explanation is this sentence:

However, this doesn't solve the mystery of who first decided to put a frog in a brick.

Clarion Ledger Sun - Aug 16, 1925

Posted By: Alex - Mon May 23, 2022 -

Comments (5)

Category: Animals, Science, Experiments, 1920s

Stock Show Beauty Queens of 1956 and 1957

Posted By: Paul - Mon May 23, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Contests, Races and Other Competitions, Regionalism, 1950s

Charles Davis, collector of elephant hairs

Charles Davis collected elephant hairs — in particular the long hairs that grow from their tails. By the time he was 83, in 1962, he had hairs from 357 different elephants.

Cincinnati Enquirer - June 14, 1959

Details from a syndicated article by Ramon J. Geremia (Weirton Daily Times - Mar 24, 1962)

But the elephant hairs make up the bulk of the collection of elephantiana. The longest one is 13 inches, the shortest, plucked from a 200 pound baby elephant, is one and one-half inches long. They include colors ranging from black to white with a few red chin whiskers.

Most of them were plucked from elephant tails — some were cut from the more belligerent behemoths. Every zoo in the nation is represented, except the Bronx Zoo in New York...

Davis started his unusual hobby as an elephantphile in 1928. He asked a circus elephant trainer to suggest something he could collect from or about elephants and the trainer suggested hair. Davis, a retired optometrist, says his collection "took my mind off business."

Posted By: Alex - Fri May 20, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Collectors, Hair and Hairstyling

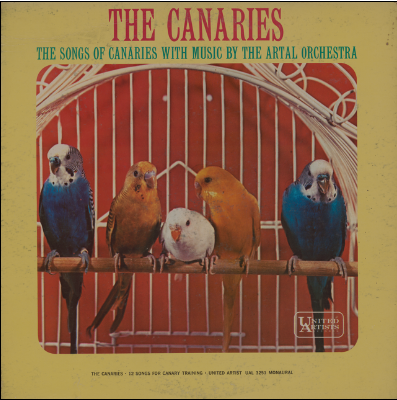

Canary Sing-along

Pet birds making their traditional sonic calls while classical music plays.

This little player starts at track one and goes through the whole album. But if you'd like to skip right to your favorite, go here.

Posted By: Paul - Wed May 18, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Animals, Music, 1960s

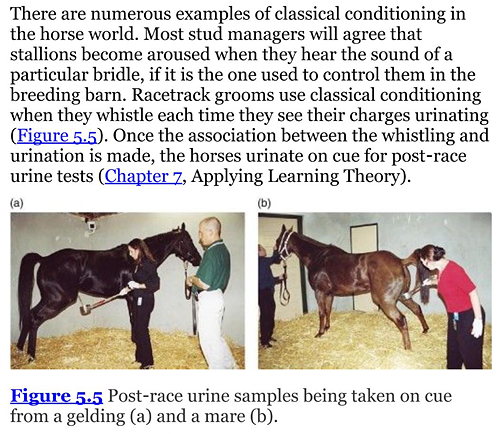

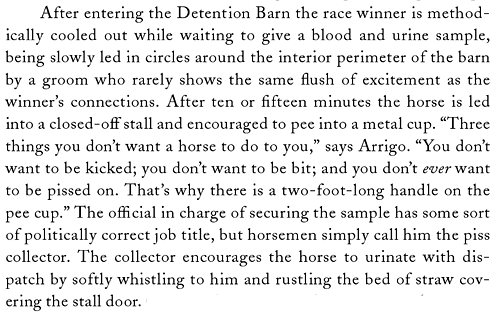

Whistle-Trained Horses

Odd fact: Race-horse trainers teach the horses to urinate when they hear a whistle, in order to make the process of post-race urinalysis easier.

Source: Equitation Science, 2nd ed.

Source: The Blue Collar Thoroughbred

Posted By: Alex - Sat May 07, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Body Fluids

Tank Pigeons

Tanks were first used in combat during World War I, but they often relied on a very old-fashioned form of communication: pigeons.From military-history.org:

A pigeon about to be thrown from a tank during World War I

Posted By: Alex - Sun May 01, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Animals, Military, War, 1910s

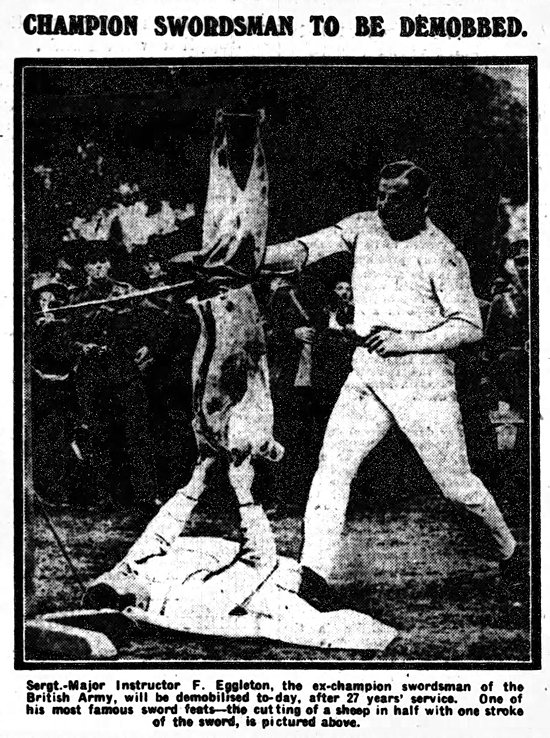

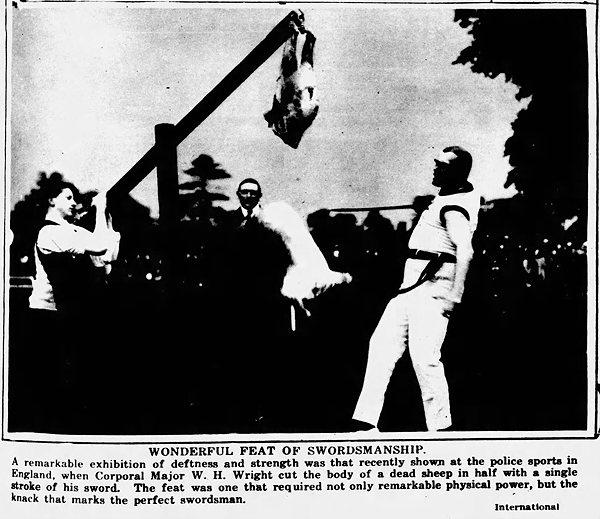

Cutting a sheep in half with one stroke

Swordsmanship shows often used to include demonstrations of the ability to cut a dead sheep in half with one stroke.I've never been to a swordsmanship show, but I'm guessing that this particular display of ability is no longer a standard routine.

I'm also guessing that it must be pretty hard to do.

Birmingham Gazette - Apr 16, 1920

Ithaca Journal - Sep 23, 1922

Posted By: Alex - Wed Apr 06, 2022 -

Comments (6)

Category: Animals, Weapons

CHANGE RETURN

Posted By: Paul - Tue Apr 05, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Technology, Poor People, Poverty, Proles, and the Underclass, Science Fiction, Cartoons

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |