Architecture

The Escalators of Wyoming

Apparently it's "one of Wyoming’s default trivia tidbits" that there are only two escalators in the entire state. I just learned that piece of trivia.The escalators are both located in the city of Casper inside banks. One is at the main branch of Hilltop National Bank. The other is in the downtown branch of First Interstate Bank.

First Interstate Bank escalator

Hilltop Bank escalator

An article at Cowboy State Daily (source of the above images) delves into some more details about the escalators.

For instance, there used to be a third escalator located in a Cheyenne JCPenney, but it was torn down when JCPenney moved.

Also, the two existing escalators were built in 1958 and 1979. This means that it's now been 45 years since an escalator was installed in Wyoming.

The scarcity of escalators is down to a) a lack of people in the state, and b) a lack of multi-story buildings.

I think Wyoming should make an effort to get rid of the two escalators. Then it could boast of being the only escalator-free state.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Dec 11, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Architecture

The Sonata of Sleep

The Sonata of Sleep wasn't a musical composition. Instead it was a building designed (but never built) in the 1930s by Soviet architect Konstantin Melnikov. He envisioned it as a place where Soviet workers could enjoy scientifically-enhanced sleep. Details from Cabinet magazine:At either end of the long buildings were to be situated control booths, where technicians would command instruments to regulate the temperature, humidity, and air pressure, as well as to waft salubrious scents and “rarefied condensed air” through the halls. Nor would sound be left unorganized. Specialists working “according to scientific facts” would transmit from the control centre a range of sounds gauged to intensify the process of slumber. The rustle of leaves, the cooing of nightingales, or the soft murmur of waves would instantly relax the most overwrought veteran of the metropolis. Should these fail, the mechanized beds would then begin gently to rock until consciousness was lost.

Model of Melnikov's Sonata of Sleep

image source: interwoven

Posted By: Alex - Sun Oct 20, 2024 -

Comments (8)

Category: Architecture, Sleep and Dreams, 1930s, Russia

Slammed door, house fell down #2

Four years ago we posted about the case of Mary Adams of Stockport, England, who slammed her front door shut, causing the house to fall down.The exact same thing happened to Claudine Rossi of Caderousse, France in 1971. She left her house to go shopping, slammed the front door shut, and the whole building fell down.

If I can find one more example of this phenomenon, I'll classify it as 'no longer weird'.

Daily Mirror - Oct 23, 1971

Posted By: Alex - Fri Oct 04, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Architecture, 1970s

Flying Saucer Gas Stations

In a previous post we looked at Soviet bus stops. It turns out that the Soviet era produced some weird gas stations as well. In particular, the flying saucer gas stations of Kyiv.They looked cool, and made it so that one didn't need to worry about which side of the car the fuel tank was on.

But they had a tendency to leak fuel from overhead and had high maintenance costs. So they were eventually abandoned.

More info: Rare Historical Photos; Design You Trust

Posted By: Alex - Fri Aug 09, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Architecture, Cars

The Psychology of Doorknobs

Marketing psychologist Ernest Dichter argued that home buyers place great emphasis on the feel of doorknobs when looking at a house, because "The doorknob offers the only way you can caress a house."Clipping from "Emotion brings out the buying power," by Roger Ricklefs in The Sunbury Daily Item (Nov 21, 1972):

Why do big doorknobs help sell a house? Why do some men become irrationally hostile when their sock drawers are empty? Such are the questions that intrigue researchers like Mr. Dichter...

in the past two or three years Du Pont, Alcoa, General Mills, Procter & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive, Johnson & Johnson, Schenley Industries and dozens of other well-known companies have commissioned studies from Mr. Dichter's Institute for Motivational Research here. The institute has annual volume of $600,000 and profits of $80,000 to $100,000.

Many people find Dichter's interpretations far-fetched. But people who accept the basic beliefs of modern psychologists find them quite plausible.

The psychologist says he's found that even a commonplace object like a doorknob has a surprising emotional significance to buyers.

"The doorknob offers the only way you can caress a house; you can't caress the walls," he says. "The way a product fills a hand is very important. How a handle does this will make an engineer prefer one technical product over another — and he doesn't even realize it," Mr. Dichter says.

During part of a baby's embryonic development, the thumb fills the palm of the hand, Mr. Dichter says. The new-born infant thus exhibits a strong desire to grasp objects, possibly to fill the palm of the hand again, the psychologist adds.

As he sees it, the same instinct later prompts a sub-conscious tendency to judge a house by its doorknob or a tool by its handle. Mr. Dichter says these findings and theories prompted a California lockmaker to enlarge the doorknobs it manufactured.

Even men's socks can inspire passion, Mr. Dichter asserts. "We find that an empty sock drawer is a symbol of an empty heart," Mr. Dichter said in a study for Du Pont's hosiery section. "When the husband finds that his sock drawer is not overflowing, he interprets his wife's neglect as symptomatic of her lack of consideration, concern and love."

source: The Advertising Age by John McDonough

San Francisco Examiner - Sep 2, 1966

More info: Ernest Dichter (wikipedia)

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jul 29, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Architecture, Psychology

The Tacoma Home Show Queen

I find references to queens dating from the 50's to the 80's. A good run.Read an article here with great pix.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jul 08, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Architecture, Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Domestic, Regionalism, Twentieth Century

Soviet Bus Stops

Canadian photographer Christopher Herwig has been on a mission to raise awareness of Soviet bus stops. He feels that they're an under-appreciated form of architectural art, "built as quiet acts of creativity against overwhelming state control." But he warns that they're disappearing fast due to demolition.He collected together over 150 of his photographs in the 2015 book Soviet Bus Stops. More recently, a documentary film, again titled Soviet Bus Stops, follows his years-long effort to photograph the bus stops.

More info: Soviet Bus Stops

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jun 14, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Architecture, Mass Transit, Books, Documentaries, Bus

Rooftop Runway

Landing a plane on a giant treadmill mounted on top of a skyscraper. What could possibly go wrong?

Modern Mechanics - Feb 1930

Posted By: Alex - Sun May 12, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Architecture, Air Travel and Airlines, 1930s

The Bromo Seltzer Tower

The building's home page.The original tower was topped by a 51-foot revolving replica of the blue Bromo-Seltzer bottle, which was illuminated with 596 lights and could be seen 20 miles away. Due to structural concerns, the bottle was removed in 1936.

Posted By: Paul - Sun May 05, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Architecture, Excess, Overkill, Hyperbole and Too Much Is Not Enough, Regionalism, Advertising, Twentieth Century

Bridge Color and Suicide

There's a popular hypothesis that the color of a bridge can influence how many people commit suicide from it. Dark bridges are said to attract more jumpers than brightly colored ones.The most widely cited example of this effect is Blackfriars Bridge in London. It originally was black, but in 1928 it was repainted green with yellow trim. In fact, it was repainted with the specific intention of reducing suicide attempts. And sure enough, the suicide rate reportedly dropped by 30%. (More info: "The influence of color," Penn State)

Blackfriars Bridge is no longer green, but it's still brightly painted (red and white). I can't find info on how many people still jump from it. So I don't know if the color effect is still working.

Yonkers Herald Statesman - Sep 15, 1928

Blackfriars Bridge (source: wikipedia)

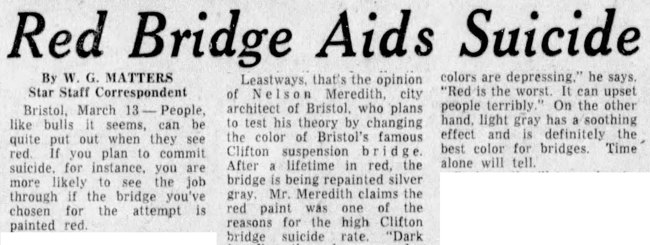

Another example is the Clifton Suspension Bridge near Bristol, England. In 1957 its color was changed from dark red to a light silver-gray — again with the specific hope of deterring suicide jumpers. Unfortunately I can't find any follow-up data to know if the color change worked.

Toronto Daily Star - Mar 13, 1957

Clifton Suspension Bridge (source: wikipedia)

The connection between bridge color and suicide seems a bit dubious to me. It would be nice if there was more substantial data to back up the hypothesis.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Nov 03, 2023 -

Comments (3)

Category: Architecture, Suicide

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |