Art

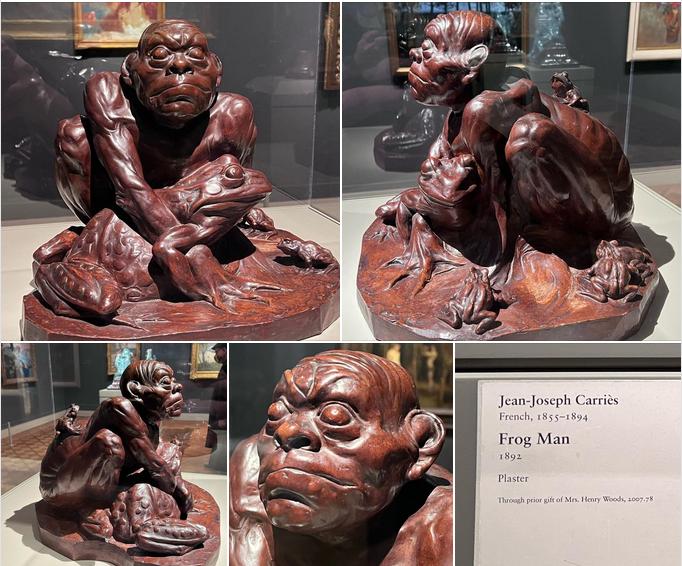

Artwork Khrushchev Probably Would Not Have Liked 48

His Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jan 26, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Art, Cryptozoology, Nineteenth Century

The Senster

Explanatory text from Are Computers Alive? Evolution and New Life Forms, by Geoff Simons (1983).Watch it in action below. The people desperately trying to get its attention clearly hadn't watched enough horror movies to know what usually happens next in situations with sentient machines.

More info: senster.com

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jan 25, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Art, Technology, AI, Robots and Other Automatons, 1970s

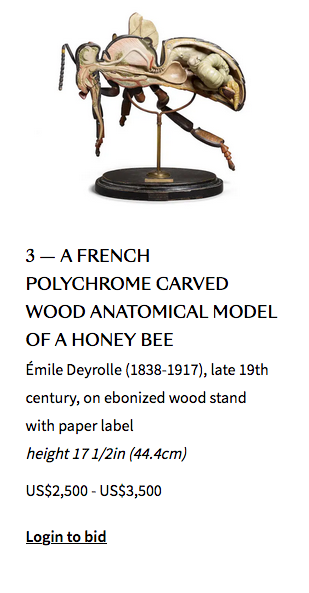

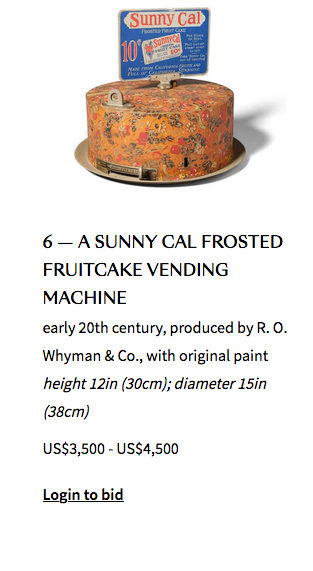

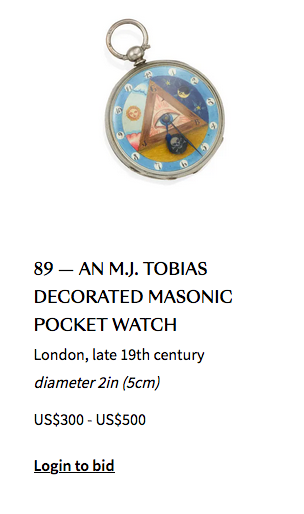

Bonham’s Auction of Curated Curiosities

View more items here. Auction kicks off January 25th.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jan 11, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Art, Souvenirs, Mementos, and Tchotchkes, Auctions, Estate Sales, Ebay and other Bidding Venues

Dogs in Uniform

For prices starting at around $400 (converted from £330), you can get an oil painting of your dog in uniform.No mention of cats in uniform, but I'm guessing that if you're willing to pay for it, they'd be willing to paint it.

More info: Fabulous Masterpieces

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jan 07, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Art, Military, Dogs

Is it art, or is it a medical emergency?

London police recently responded to a report of a woman in an art gallery who appeared to be unconscious. The gallery was closed, but the non-moving woman could be seen through a window. So, "officers forced entry to the address, where they uncovered that the person was in fact a mannequin."The mannequin was part of a sculpture by American artist Mark Jenkins depicting the time his sister had "passed out and buried her face in a plate of soup."

More info: artnet.com

Posted By: Alex - Wed Dec 28, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Art, Confusion, Misunderstanding, and Incomprehension

Endogen Depression—Turkeys and TV sets

The art installation "Endogen Depression," by Wolf Vostell, consisted of 30 television sets, partially cast in concrete, and five live turkeys.Vostell presented this installation once in the U.S., at the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art, in December 1980.

source: LA Public Library

Text from the LA Times (Dec 17, 1980):

Vostell means to contrast the sophistication of TVs and turkeys. The birds win handily. He also feels we can learn more from reputedly stupid turkeys than from television, but the comparison may not be a fiar one. The TV drone is so familiar and the programming so low-level, we quickly accept it as easily tuned-out background noise. Turkeys, on the other hand, look downright exotic to city folks who have never encountered one off a serving dish and wearing its feathers.

You can check out a video of the turkeys and TVs from the 1980 event at vimeo.com (embedding was disabled).

Posted By: Alex - Sun Dec 18, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Art, Television, 1980s

Artwork Khrushchev Probably Would Not Have Liked 47

The Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Nov 27, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Art, Avant Garde, 1950s, Europe, Russia

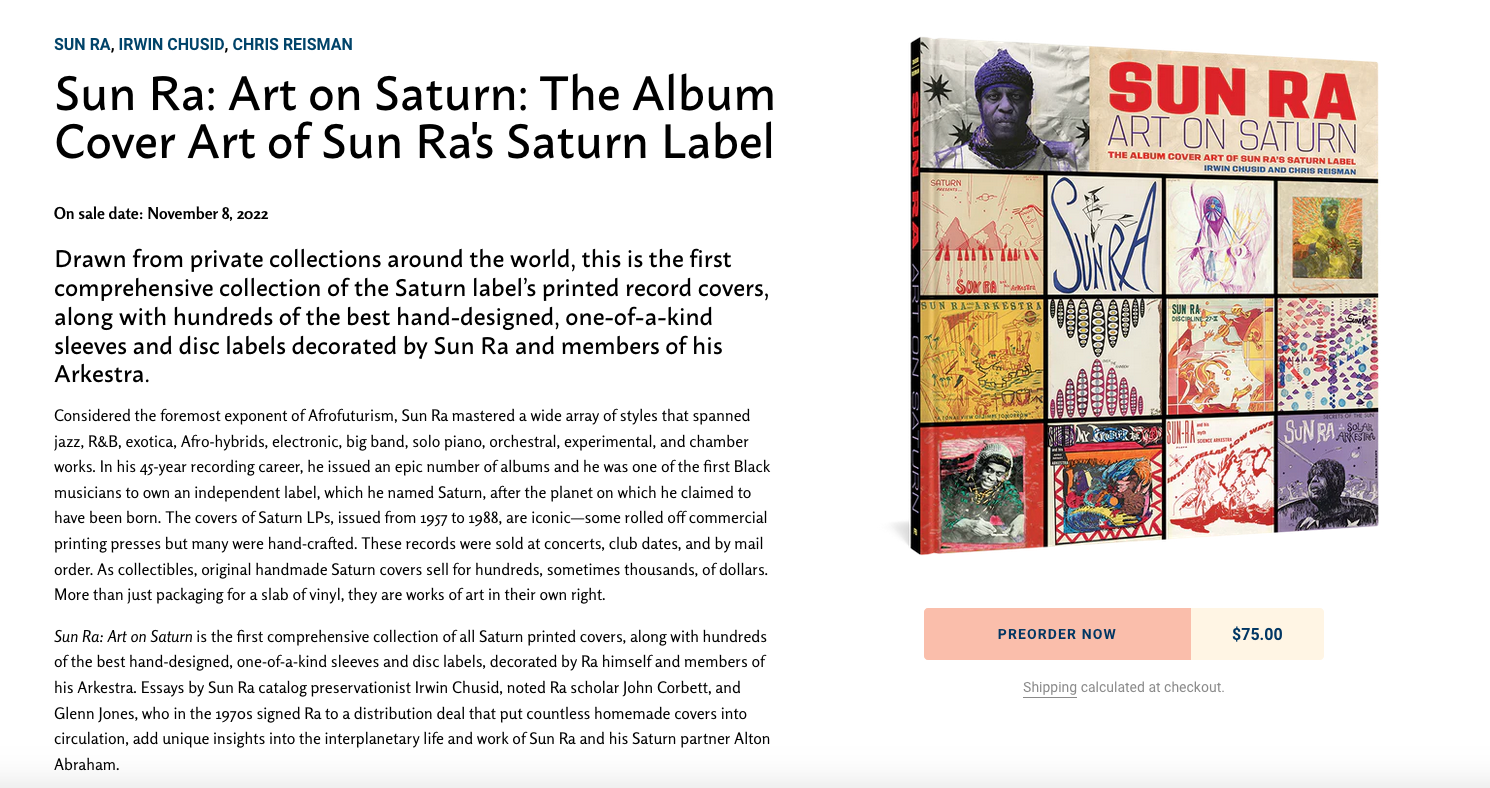

Sun Ra Cover Art Book

Looks like a great Xmas present for WU-vies.Here's the publisher's page, with the Amazon link below.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Nov 01, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Art, Eccentrics, Holidays, Music, Vinyl Albums and Other Media Recordings, Books

Upside-Down Mondrian

Art historian Susanne Meyer-Büser argues that a 1941 work by Piet Mondrian has been hung upside-down for the past 75 years. The work, made with colored adhesive tape, has traditionally been hung with the closely-spaced bands at the bottom. Meyer-Büser says that these should be at the top, "like a dark sky." A photo of Mondrian's studio from 1944 supports her interpretation.However, there are no plans to turn the work around, due to its fragile condition.

I'll be adding this to my Gallery of Art Hung Upside-Down.

More info: BBC, Town and Country

The traditional orientation

The correct orientation (according to Meyer-Büser)

Posted By: Alex - Sun Oct 30, 2022 -

Comments (6)

Category: Art

Artwork Khrushchev Probably Would Not Have Liked 46

Two links to the Wikipedia pages of the Themersons, husband and wife team of avant-gardists.Small essay here.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Aug 31, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Art, Avant Garde, Surrealism, Movies, Twentieth Century

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |