Books

Cooking for your cat… and you

For those who want to share meals with their cat, Skyhorse Publishing has a cookbook of recipes that both humans and felines can eat.I don't think freshly caught mouse is included, even though I'm pretty sure that's what the cat would prefer.

Amazon link

Posted By: Alex - Fri Nov 06, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Cookbooks, Books, Cats

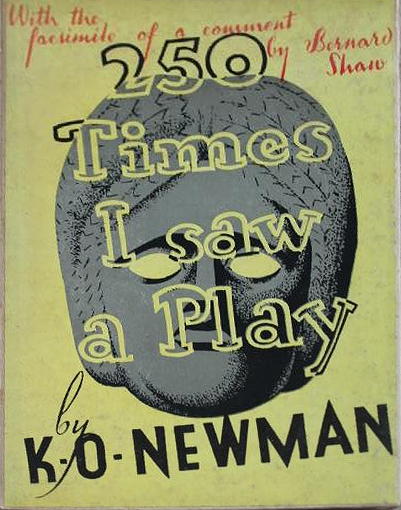

250 Times I Saw a Play

Keith Odo Newman, whom the Guardian has described as "a homosexual Austrian psychoanalyst," authored 250 Times I Saw A Play, which was published in 1944. As the title suggests, it describes his experience of watching a play 250 times. The play was Flare Path by Terence Rattigan.

The backstory here is that Newman was Rattigan's doctor. According to TactNYC.org:

For some reason, Rattigan asked Newman to personally direct the performance of the lead actor in the play, Jack Watling, and Newman proceeded to become obsessed with Watling. Which is why, I assume, Newman ended up watching the play 250 times. Rattigan's biographer, Geoffrey Wansell, offers more details:

At this stage Newman had not made a homosexual pass at Watling. That came later. Newman simply frightened him beyond words. 'I couldn't do anything without asking his permission. I was heterosexual then, and I am now, but Newman pretty much gave me a nervous breakdown. I couldn't cope with him.' Why Newman had this power, or why people submitted to him, Watling is just as unable to explain now as he was then.

After completing his odd book, Newman sent the manuscript to George Bernard Shaw, who wrote back with a few of his thoughts about it. Shaw's comments weren't very complimentary, but Newman nevertheless included a facsimile of them at the front of the book. Shaw wrote:

Sure enough, Newman was subsequently certified insane and died in a mental institution.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 02, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Theater and Stage, Books, 1940s

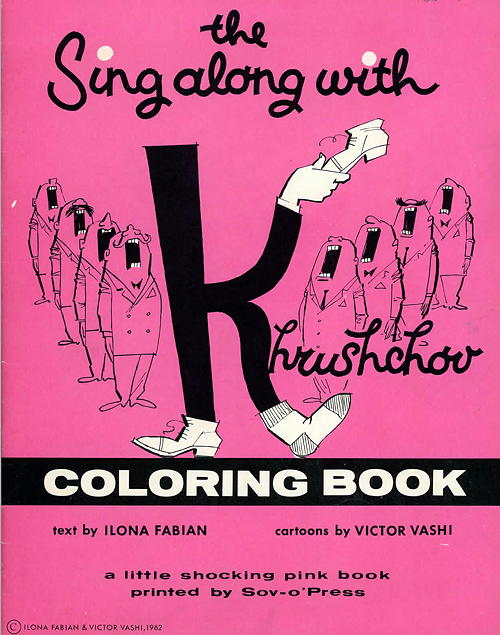

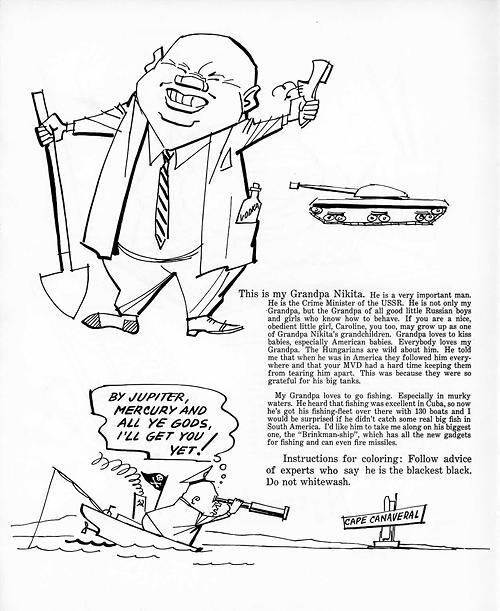

Sing along with Khrushchov coloring book, an update

Eight months ago I posted about a coloring book published in 1962 titled The Sing Along with Khrushchov Coloring Book. I noted that, although I had come across references to the book in newspapers, I hadn't been able to find any images of it online. Nor were there any used copies for sale. And only two libraries in the U.S. had copies of it. It was really obscure!But I was just contacted by Elaine Woodward who revealed that her grandfather, who was on the American Hungarian Federation in DC, had once given her a copy, which she still had. She was kind enough to scan it and send it to me. So here it is, rescued from obscurity!

I've posted two sample images below. Or click here to read the whole thing (pdf file).

Note that the book spells Khrushchev with an 'o' rather than an 'e'... so the title was misspelled in my original post.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Oct 12, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Art, Dictators, Tyrants and Other Harsh Rulers, Politics, Books, 1960s

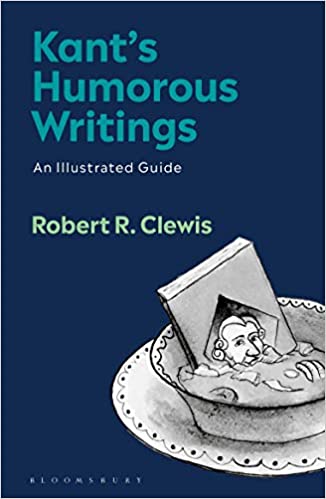

The jokes of Immanuel Kant

We've posted before about jokes from unlikely sources, such as the jokes of Lord Aberdeen, and the jokes of King George VI. Now, along similar lines, comes a book from Robert Clewis — Kant's Humorous Writings . It's a collection of 30 jokes told by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant.

Kant and humor are, I'm guessing, two things most people wouldn't associate together. And after reading Clewis's book, their opinion on this subject may not change.

Clewis freely admits this. In his preface he notes that he was "once tempted to call the book Kant’s Humorous Writings: I Wish They Existed." He goes on to say, "Readers may find the jokes to be boring or even offensive. No promise is being made that the reader will find the jokes amusing."

But Clewis also insists that the book itself isn't a joke. Nor was his intent to lampoon Kant. As he describes it, while studying Kant he realized that the philosopher's work included occasional jokes. His curiosity aroused, he thought it would be interesting to collect these jokes together, as a way of understanding what Kant thought was amusing.

Each joke is accompanied by an illustration drawn by artist Nicholas Ilic. So it's very much a book geared for a general audience. (Admittedly, an audience who appreciates offbeat, erudite material). Personally I think it seems like a great coffee table book. But then, I'm strange that way.

I've reproduced two of Kant's jokes, as well as Clewis's explanation of them, below.

Amazon link

There was once a young merchant who was sailing on his ship from India to Europe. He had his entire fortune on board. Due to a terrible storm, he was forced to throw all of his merchandise overboard. He was so upset that, that very night, his wig turned gray.

Explanation:

This joke comes from the Critique of the Power of Judgment (1790), one of Kant's three Critiques. He contrasts this version with another version: the merchant's hair turns gray. But in that version, we listeners or readers become more concerned and involved. We empathize with the merchant and feel his pain more than in the first version. When it's just a wig, we are in a better position to find the story amusing. We hear the narrative as a joke rather than as descriptive speech, a real story about the world that can be either true or false.

Kant thinks that when we hear or read a joke as a joke, we need to be removed from the situation or story; we cannot have something at stake in it. He calls this disinterestedness, which turns out to be a key principle in his aesthetic theory and account of beauty. "Taste is the faculty for judging an object or a kind of representation through a satisfaction or dissatisfaction without any interest. The object of such a satisfaction is called beautiful." While the humorous is not the same as the beautiful, Kant thinks that our response to both of them requires a kind of disinterestedness. A notion of disinterestedness can be found in the writings of Shaftesbury (Anthony Ashley Cooper) (1651–1713) and other eighteenth-century aesthetic theorists. Today the notion of disinterestedness remains controversial. Some theorists think that the idea can be better captured by the concept of absorbed attention or focus.

Immanuel Kant

A man's rich relative dies. Suddenly he is rich. To honor his relative, the man wants to arrange a solemn funeral service. But he keeps complaining that he can't get it quite right.

"What's the problem?" someone asks.

"I hired these mourners, but the more money I give them to look grieved, the happier they look."

Explanation:

This is a second joke from the Critique of the Power of Judgment. Kant is using it to illustrate his incongruity theory of humor. When we learn that the mourners are happy because they are getting paid, he says, our expectation is suddenly "transformed into nothing."

The philosophical underpinning is that there are at least two levels of satisfaction at work: we feel sadness, joy, etc. (first-order satisfaction) and then can approve or disapprove of it using reason (second-order). A man can be glad that he is receiving an inheritance from a deceased relative, yet disapprove of his gladness. "The object can be pleasant, but the enjoyment of it displeasing."

The joke turns on something similar happening with the mourners. They are so happy that they are getting paid (second-order) that they are no longer able to look sad (first-order).

There is a similar anecdote in Plato's Ion, a dialogue about a professional reciter (a "rhapsode") named Ion, who aimed at moving his audience. Ion says that when he looks out at the audience and sees them weeping, he knows he will laugh because it has made him richer, and that when they laugh, he will be weeping about losing the money.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Sep 28, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Humor, Jokes, Philosophy, Books

Ice Cream for Small Plants

Authored by Etta Howes Handy and published in 1937 by The Hotel Monthly Press.Of course she means manufacturing plants, but I prefer to imagine people feeding ice cream to their house plants.

Amazon link

Posted By: Alex - Sun Sep 13, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Food, Books

The Techno-Chemical Receipt Book

This is one of those volumes you pack away for when civilization collapses, as it give the formulas for making from scratch glass, nitroglycerin, glue, and a thousand other handy things.

Read it here.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Sep 13, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Science, Technology, Books, Nineteenth Century

The Right To Be Lazy

Happy Labor Day!What better way to spend this annual celebration of work than by reading Paul Lafargue's 1883 treatise The Right To Be Lazy, in which he made a case for the virtues of idleness.

Some info about Lafargue and The Right To Be Lazy from RightNow.org:

Much of the book consists of a contrast between ideas about work in Lafargue’s day and the very different attitudes held in earlier societies, particularly in classical antiquity. Ancient Greek philosophers regarded work as an activity fit only for slaves. So where others hailed the arrival of modern industry as progress, Lafargue saw regression.

Longtime WU readers might remember that we've posted about Lafargue before. He made headlines back in 1911 for his unique retirement plan, which consisted of divvying up all he had for ten years of good living and then killing himself when the money ran out.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Sep 07, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Jobs and Occupations, Utopias and Dystopias, Books, Nineteenth Century

The Big Book of Mars

Friend of WU Marc Hartzman recently came out with The Big Book of Mars (published by Quirk Books, a division of Penguin Random House), and I was lucky enough to get a copy.

For anyone who's a Mars buff, the book is a must-have. Marc has collected together a smorgasbord of Martian-related weirdness. For instance, I was wondering if he'd cover the Martian beavers that I posted about a few weeks ago. And sure enough, the beavers are in there!

I've also been intrigued by his account of weirdo scientist Francis Galton, back in 1896, studying what he believed to be flashing light signals from Mars. Galton claimed to have decoded words such as 'brackets', 'circumference', and 'Jupiter'. Scientists now believe Galton was seeing sun flashing off the Martian polar ice.

Really, anyone who's at all curious about Mars, or just likes weird history, will enjoy the book. Plus, it's the kind of book that would look great on a coffee table as almost every page contains gorgeous, full-color illustrations.

Definitely recommended!

Amazon, Barnes & Noble

Marc's website

Posted By: Alex - Tue Aug 18, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, Books

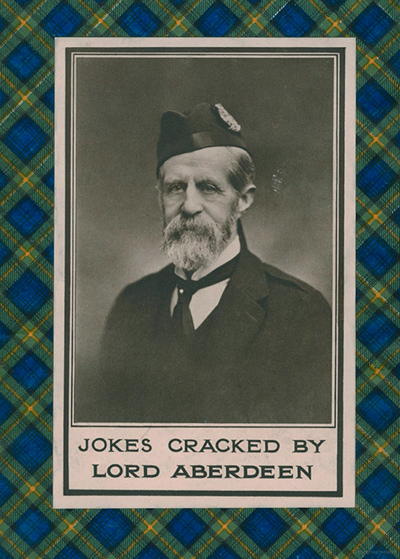

Jokes Cracked By Lord Aberdeen

Lord Aberdeen (1847-1934) was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1886, and again from 1905 to 1915. He held the office of Governor General of Canada from 1893 to 1898. He also fancied himself something of a wit and allowed some of his jokes to be collected together in a volume titled Jokes Cracked by Lord Aberdeen, published in 1929 by Valentine Press.Over the years, the book became a cult classic, due to its reputation as the worst joke book ever published. On the strength of this reputation, it was republished in 2013 (available on Kindle for $1.99).

In reality, the jokes aren't all that bad. However, they are liberally sprinkled with Scottish dialect, which can make them hard to understand. Also, their subject matter is often quite dated.

But judge them for yourself. I've collected together some examples below.

You probably failed to get that joke. I certainly had no clue what the punchline meant. Here's an explanation by John Finnemore (who wrote the intro to the 2013 edition):

More jokes (easier to understand):

'Well, but,' replied the bishop, 'I don't know your aunt.'

The wife seemed rather dubious, but replied, "Well, I suppose he micht try."

"All right" said the doctor, "I had better call again in a few days to see how he does."

And sure enough, in due course, the doctor arrived and on asking the wife how the new diet was suiting her husband, received the following reply:

"Weel, he manages middlin' well wi' the neeps; and whiles the linseed cake, but oh! doctor, he canna thole the strae!"

('he canna thole the strae' = he cannot stand the straw)

In this way an element of permanence is secured for the assistant or colleague, since, humanly speaking, it is only a matter of time when he will have full charge, and the full stipend, such as it may be.

I remember that the late Dr. Marshall Lang, who was a Moderator of the Church of Scotland, and latterly Principal of the University of Aberdeen, when speaking on a subject which included the above arrangement, said that he had heard of an elderly minister who once said to his "assistant and successor:" "I suppose, my young friend, you are 'thinking long' for my dying?"

"Ah, no, sir," replied the younger man, "you must not put it so; for it is your living that I desire."

Sandy: "I noticed that, when I was takin' up the collection."

More in extended >>

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 12, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Books, Jokes

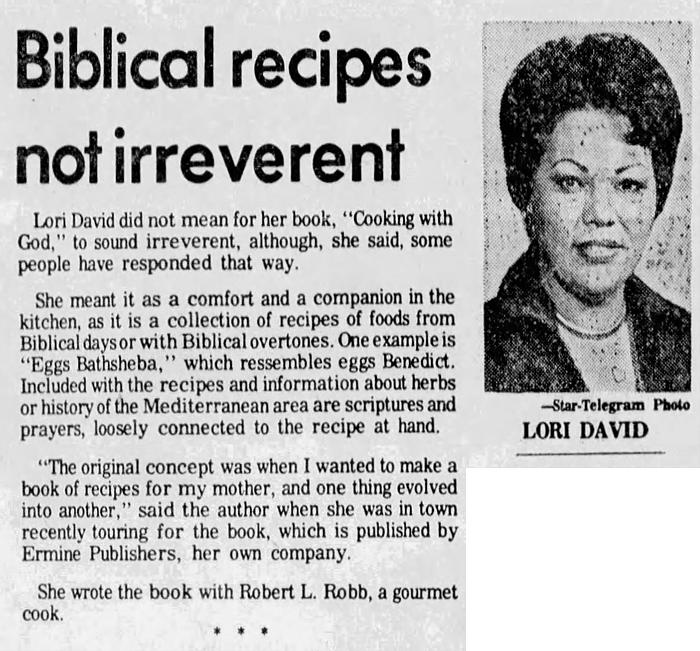

Cooking with God

Poe's Law, loosely paraphrased, states that it can be very difficult to tell the difference between parodies of extreme beliefs and sincere expressions of those beliefs.Confusion of this kind occurred with the 1976 cookbook Cooking With God. The authors, Lori David and Robert Robb, intended it to be, in all seriousness, a religious-themed cookbook. But due to the title, many people apparently assumed it was some kind of joke.

Recipes included Manna Honey Bread, Oasis Stuffed Eggs, Caravan Sweet Potatoes, and Eggs Bathsheba.

If you want a copy to add to your collection of weird cookbooks, you can pick one up used on Amazon for $6.95.

Fort Worth Star Telegram - Mar 16, 1977

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 05, 2020 -

Comments (5)

Category: Food, Cookbooks, Religion, Books

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |