Computers

Media Franchises Seen Through an AI Redneck Filter

I hate to bow down to our AI masters, but these videos--music and animation all done by AI--are pretty cool.Others found here.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Feb 24, 2025 -

Comments (0)

Category: Hollywood, Technology, Computers, Homages, Pastiches, Tributes and Borrowings, Twenty-first Century

Music From Mathematics

The first track is embedded here. The rest of the playlist is at the link.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Jan 26, 2025 -

Comments (4)

Category: Music, Computers, 1960s

Automan

As Wikipedia tells us:Automan is an American superhero television series produced by Glen A. Larson. It aired for 12 episodes (although 13 were made) on ABC between 1983 and 1984. It consciously emulates the visual stylistics of the Walt Disney Pictures live-action film Tron, in the context of a superhero TV series.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jan 14, 2025 -

Comments (0)

Category: Ineptness, Crudity, Talentlessness, Kitsch, and Bad Art, Motor Vehicles, Police and Other Law Enforcement, Technology, Computers, Television, 1980s

Miss Calculator of 1952

I've been unable to find out if Ruth Houser ended up winning the title of "Miss Calculator of 1952."Incidentally, the Monroe Calculating Company is still around, and still selling calculators.

Johnson City Press-Chronicle - May 18, 1952

Posted By: Alex - Sun Sep 01, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Technology, Computers, 1950s

Copilot Prompt: “Please make a symbolic visual representation of the website http://weirduniverse.net/”

Posted By: Paul - Tue May 28, 2024 -

Comments (6)

Category: Art, Weird Universe, Computers

Reconstructing shredded paper money

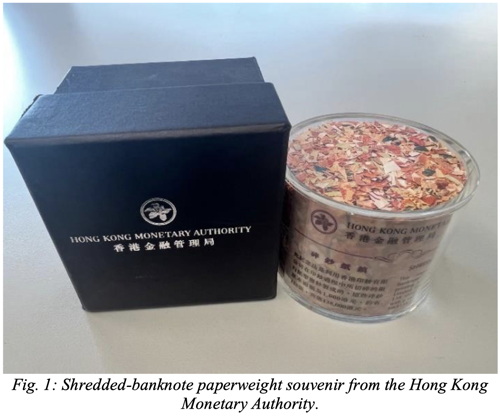

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority visitor center sells souvenir glass containers full of shredded paper money. Each container (costing $100 HKD) is advertised as containing 138 complete $1000 HKD banknotes.Researcher Chunt T. Kong set out to determine whether he could use "computer vision" to reconstruct the shredded banknotes. If he could, this would mean that for an investment of $100 HKD he would be able to reconstruct notes worth $138,000 HKD.

He determined that, yes, in theory the banknotes could be reconstructed. But he encountered a few problems:

First, the souvenir containers often contained far fewer than 138 notes. Some had as few as 20 notes in them. He found stones hidden in some of the containers. This, he complained, was false advertising. He noted, "it appears that the Hong Kong Monetary Authority has broken the law."

The second problem: "even though the shredded banknote pieces could construct a complete banknote, the serial number may not have come from the same banknote, and there is a high chance that it could not be exchanged for real money."

He didn't address how all the little pieces would be stuck back together. With scotch tape?

But, of course, it was all just a theoretical exercise. Though he says that, having informed the Hong Kong Monetary Authority visitor center of what he did, they're now no longer selling the shredded money.

More info: "The possibility of making $138,000 from shredded banknote pieces using computer vision"

via New Scientist

Posted By: Alex - Sat May 04, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Money, AI, Robots and Other Automatons, Computers

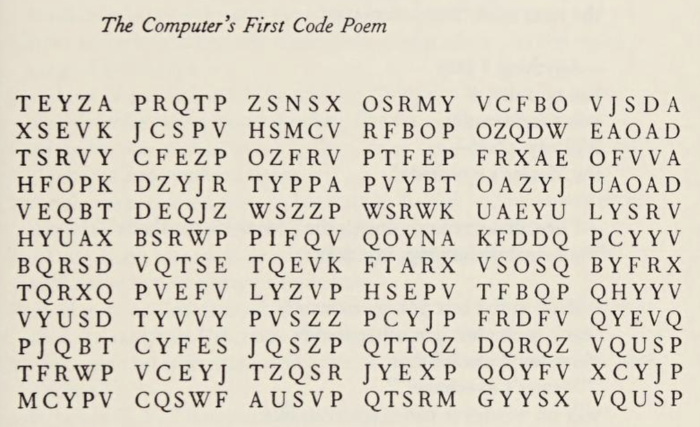

The Computer’s First Code Poem

Scottish poet Edwin Morgan included "The Computer's First Code Poem" in his 1973 collection From Glasgow to Saturn.

Despite what the title may imply, Morgan didn't actually program a computer to produce the poem. (Nor did he have the Loch Ness Monster pen "The Loch Ness Monster's Song" in the same collection.) However, the poem really is in code, as he later explained:

I didn't bother to try to crack the code. Instead, I found someone online (Nick Pelling) who had done it. Apparently it's a simple letter-substitution code, which produces:

dirty whist fight numbs black rebec

pinto hurls bdunt spurs under butte

fubsy clown posse stomp below xebec

tramp crawl kills kinky xerox joint

foxed minks squal above yucca shoot

manic tapir party upend tibia mound

panda strut jolts first pumas afoot

toxic potto still shows uncut aorta

swamp houri wails appal canal taxis

punks throw plain words about dhows

ghost haiku exits aping zooid taxis

That's not much more intelligible than the original poem. Pelling speculates that we can't rule out the possibility of a second hidden message within the first message.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Apr 28, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Codes, Cryptography, Puzzles, Riddles, Rebuses and Other Language Alterations, Computers, Poetry

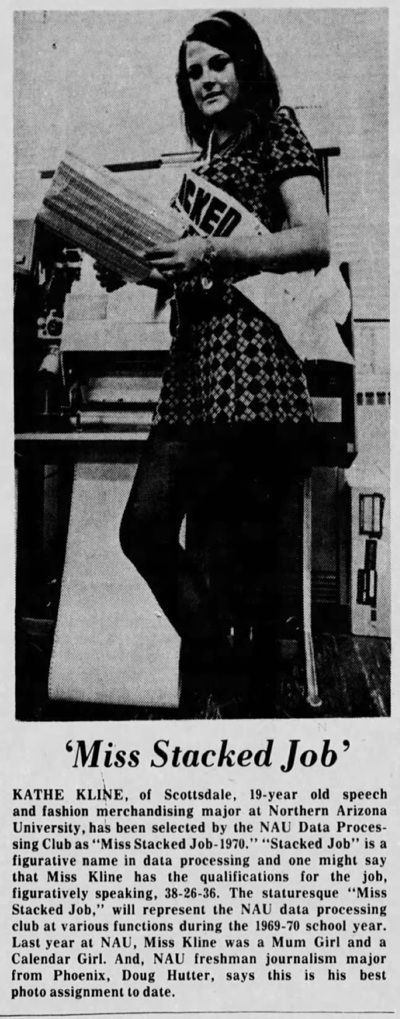

Miss Stacked Job

As far as I can tell, the term "stacked job" (as it was used in 1960s-era computing) was roughly equivalent to what today would be called 'batch processing'. It was a stack of jobs (or programs) to be run by the computer.When the Northern Arizona University Data Processing Club came up with the idea of awarding a young woman the title of "Miss Stacked Job," they admitted, "We didn't know how many, if any, girls would want the title." They ended up with ten contestants. Kathe Kline was the winner.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jan 19, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Computers, 1960s, Arizona

The Honeywell Kitchen Computer

In 1969, Neiman Marcus offered a Honeywell "kitchen computer" in its Christmas catalog. The price tag was $10,600, which is equivalent to about $80,000 today. The price included a two-week course in programming, which was required to know how to use the computer. The computer could supposedly store recipes and help housewives plan meals.No one ever bought one. Or rather, no one ever bought the "kitchen computer," but a few people (engineers, and the like) did buy the H316 minicomputer, which is what the kitchen computer really was. Neiman Marcus and Honeywell had simply repackaged the H316 as a kitchen computer.

Nevertheless, the "kitchen computer" is now credited as being the very first time a company had offered a home computer for sale. One of them is on display at the Computer History Museum.

More info: wikipedia

image source: Divining a Digital Future, by Paul Dourish and Genevieve Bell

If someone had bought one of the kitchen computers, it would have been pretty much unusable, because a user had to communicate with it in binary code, using a series of 16 buttons on the front to enter data. From Wired:

image source: The Computer, by Mark Frauenfelder

Posted By: Alex - Wed Nov 22, 2023 -

Comments (5)

Category: Technology, Computers, 1960s

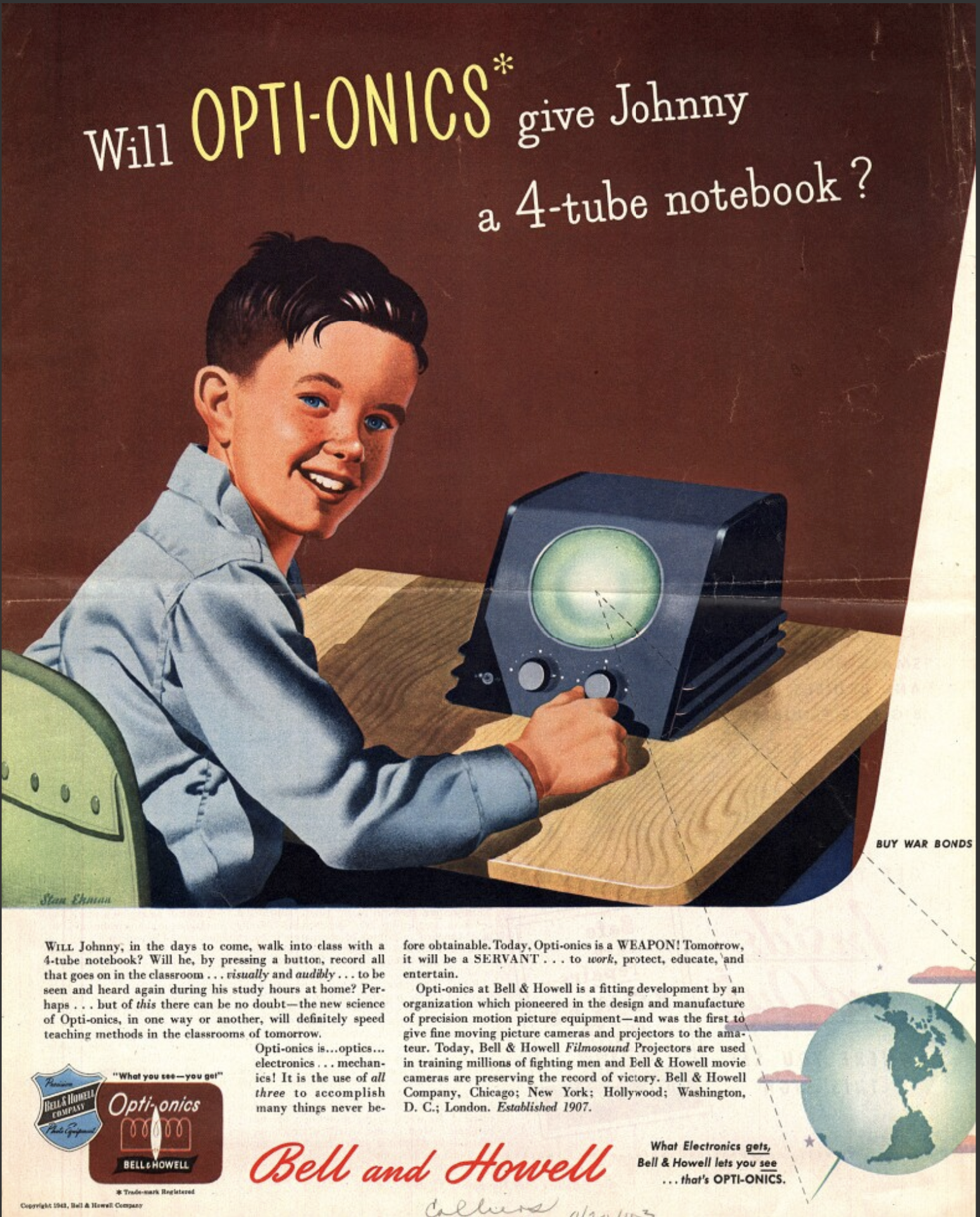

Opti-onics, the Technology of the Future

I suppose this came true, if you can say your phone and tablet use something vaguely similar to Opti-onics!Go to source to enlarge the text for reading.

Posted By: Paul - Sun May 07, 2023 -

Comments (3)

Category: Technology, Computers, 1940s, Yesterday’s Tomorrows

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |