Crime

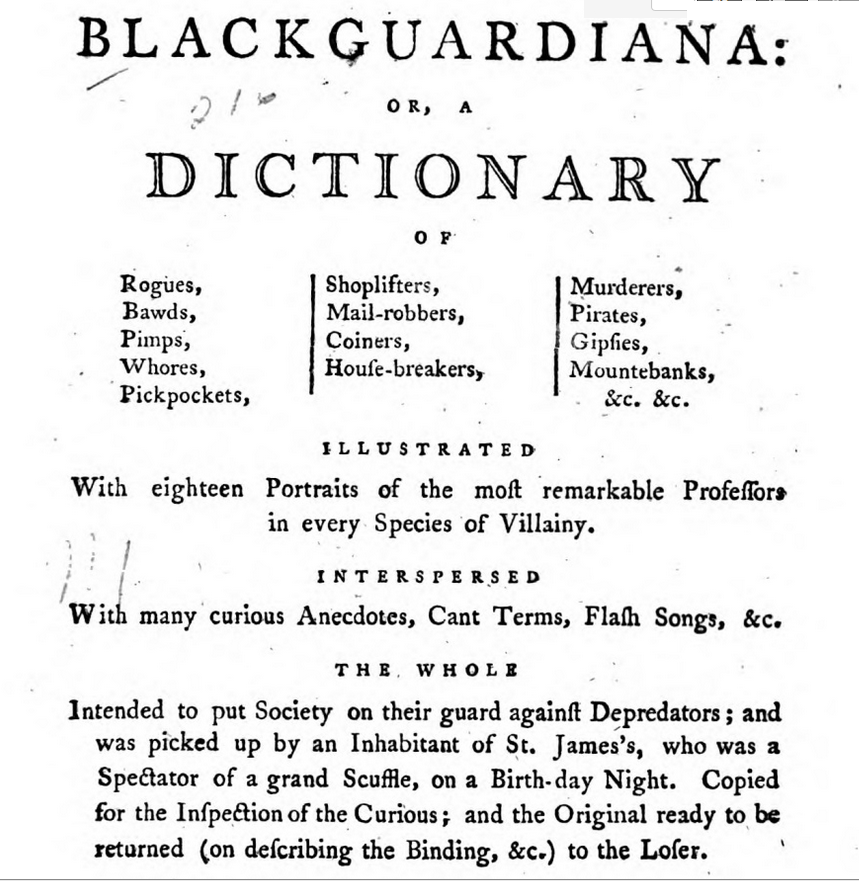

Blackguardiana

You can surely amuse yourself for hours reading this 1793 guide to rogues. And I think we should resurrect these old terms for modern times. For instance, if a woman is inconveniently pregnant, let us say she has "sprained her ankle."

Posted By: Paul - Sat Feb 18, 2017 -

Comments (3)

Category: Crime, Eighteenth Century, Slang

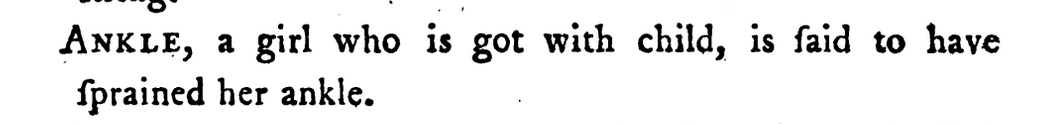

House Call from Faux Dress Fitter

Despite all the contemporary tales of ingenious upskirt photographers and toilet-cam operators, I don't believe anyone has recently utilized the "free dress comes with home fitting service" routine.

Original article here.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jan 23, 2017 -

Comments (1)

Category: Annoying Things, Crime, Domestic, Sexuality, 1950s

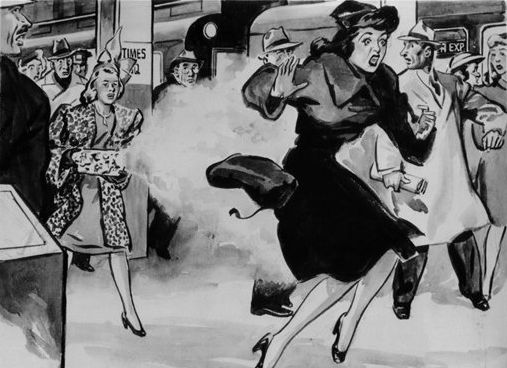

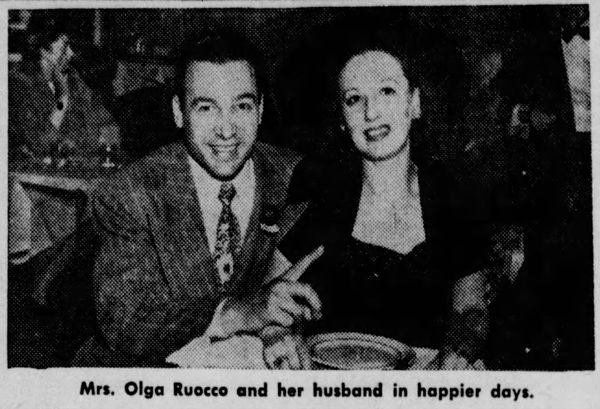

The Case of the X-Ray Camera

New Year's Eve, 1946 was the occasion of a classic weird crime.19-year-old Pearl Lusk thought she had been employed to do some detective work by Allen La Rue, whom she had met on the subway. He told her that he was an insurance investigator. Her mission was to track a suspected jewel thief, Olga Trapani, and collect evidence to build a case against her.

Lusk trailed Trapani for a few days, and then La Rue added a new twist to the assignment. He gave her what he described as an "X-ray camera" camouflaged as a gift-wrapped package and instructed her to take a picture of Trapani with it. The resulting photo, he said, would reveal the jewels that Trapani kept pinned inside her dress, around her waist.

Lusk dutifully followed Trapani into the Times Square subway station, pointed the camera at her, and pulled the trigger wire. A shot rang out and Trapani collapsed to the ground.

It turned out that the "X-ray camera" was really a camouflaged sawed-off shotgun. And Trapani was really La Rue's ex-wife, of whom he had grown insanely jealous. La Rue's real name was Alphonse Rocco. He had been stalking his ex-wife for several months.

Lusk was totally clueless about what she had done. As the subway police rushed up after the shooting, she told them, "I just took this woman’s picture and somebody shot her."

Rocco fled to upstate New York, where he died in a shootout with the police several days later.

Trapani survived, but lost her leg. She and Lusk reportedly became friends after the incident.

You can read more about the case at EinsteinsRefrigerator.com, or the New Yorker.

Philadelphia Inquirer - Jan 1, 1947

Washington Court House Record-Herald - Jan 3, 1947

Posted By: Alex - Sat Dec 31, 2016 -

Comments (1)

Category: Crime, 1940s

Bucket Head

Here's a guy who was caught on caught on camera stealing pigeons while wearing a bucket on his head and a plastic trash bag around his body. Florida, of course.More details at wsvn.com.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Dec 15, 2016 -

Comments (4)

Category: Crime, Disguises, Impersonations, Mimics and Forgeries

Automatic Devil Dog Car Alarm

Contrary to the delightful ad, alarm did not speak phrases, but merely sounded the horn, as with modern car alarms.

See the actual device here, with explanation.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Dec 13, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Crime, Technology, 1930s, Cars

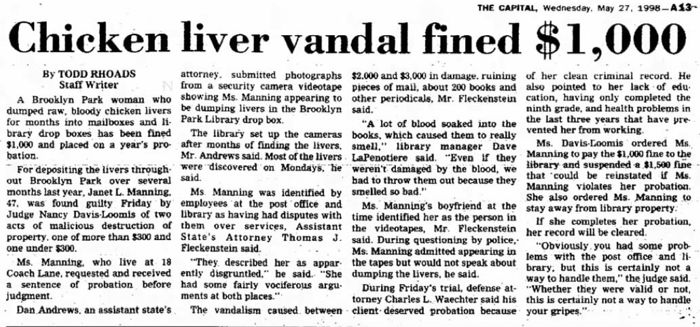

Chicken Liver Vandal

1997: The crime of choice of 46-year-old Janet Manning of Brooklyn Park, Maryland was dumping raw chicken livers into mailboxes and bookdrops. Usually on a weekend so they would be discovered on a Monday.Her motive for doing this was never very clear. After apprehending her, thanks to security-camera footage, the police captain said, "There's no clear-cut rhyme or reason for her to be doing what she was doing to these organizations." He added, "She wouldn't tell us why chicken livers."

But it was evidently some kind of act of revenge, in response to perceived offenses. Library officials recalled that she once had a minor argument with them a year before involving her request to have a printout of all the books she had returned, which the library staff told her their computers weren't set up to do. So they offered to write out the list by hand. That, apparently, was enough to trigger her.

On account of her otherwise clean criminal record, she was fined $1000 and placed on a year's probation.

The Annapolis Capital - May 27, 1998

Posted By: Alex - Sun Dec 11, 2016 -

Comments (1)

Category: Crime, Destruction, 1990s

Happy Thanksgiving 2016!

Posted By: Paul - Thu Nov 24, 2016 -

Comments (1)

Category: Crime, Food, Holidays

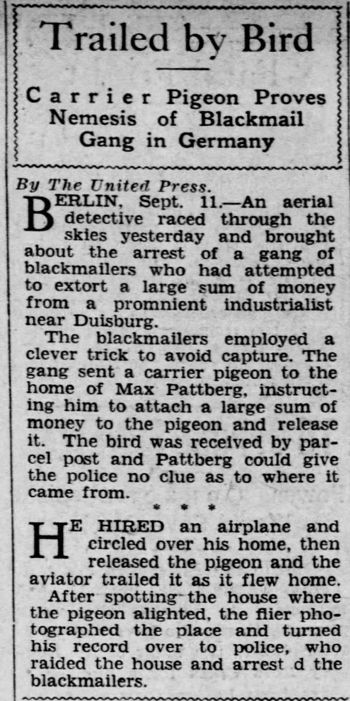

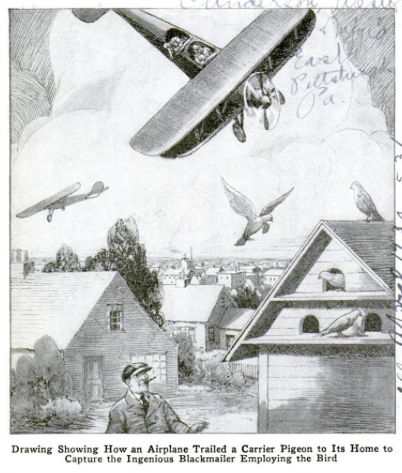

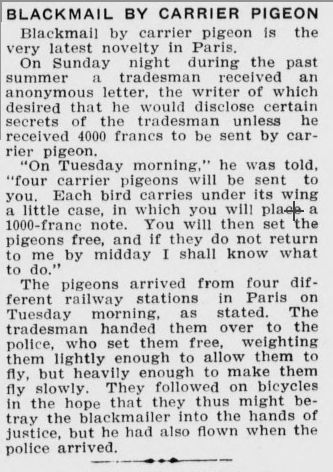

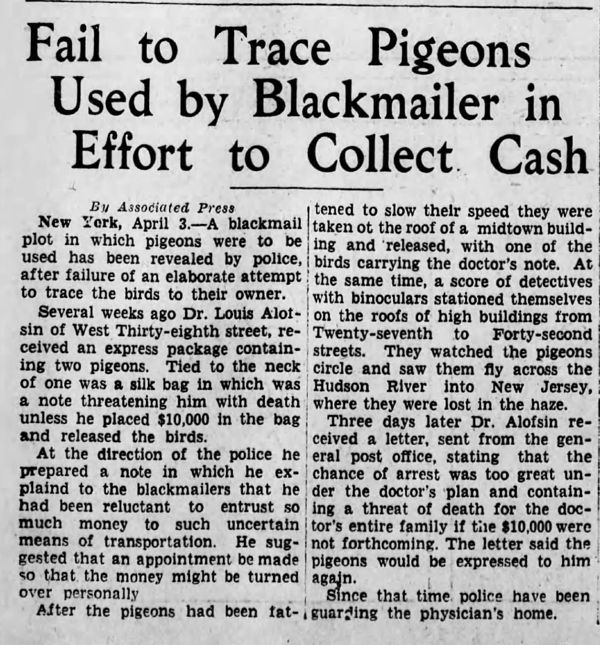

Extortion by pigeon

During the early twentieth century, an unusual method of crime enjoyed some popularity — extortionists and blackmailers demanding that payments be delivered via carrier pigeon. The criminals hoped that the pigeons would be untraceable. But as it turned out, the police often (though not always) were able to track the pigeons and capture the bad guys.

The Pittsburgh Press - Sep 11, 1929

Los Angeles Herald - Jan 2, 1910

The Harrisburg Telegraph - Apr 3, 1929

Posted By: Alex - Sat Nov 12, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Crime

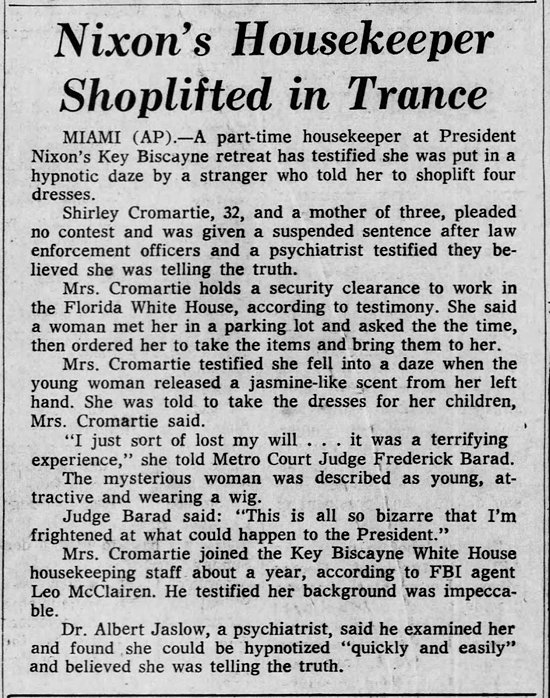

Compelled by jasmine to shoplift

Shirley Cromartie was working as a housekeeper at President Nixon's Key Biscayne retreat when, in 1971, she was arrested for shoplifting. She admitted to the crime but insisted that it hadn't been her fault. She explained that a mysterious woman wearing a wig had approached her in the store's parking lot, asked her the time, and had then released a "jasmine-like scent" from her left hand. Cromartie immediately fell into a trance, and the woman instructed her to steal four dresses, which Cromartie proceeded to do.A medical expert testified that he believed Cromartie was telling the truth.

The Philadelphia Inquirer - Oct 23, 1971

An odd story. But what are we to make of it? There's a couple of possible theories:

Theory 1: Ms. Cromartie got caught shoplifting and made up a b.s. story to explain away her actions.

Theory 2: She was totally nuts.

Theory 3: She had an encounter with an extraterrestrial! UFOlogist John Keel, author of The Mothman Prophecies, advanced this theory. He speculated that the mysterious, wig-wearing woman was actually a "woman in black" (the female counterpart of a "man in black"). He noted that "Women in Black" cases often describe them as wearing wigs, and the aliens are fond of asking people what time it is.

But why would an alien being bother to make a housekeeper shoplift some dresses? Keel speculated, "perhaps this was not some small demonstration for the benefit of President Nixon, similar to the power failures that seemed to follow President Johnson in 1967. (The lights failed wherever he went ... from Washington to Johnson City, Texas, to Hawaii)."

More info: mysteriousuniverse.org

Posted By: Alex - Tue Oct 18, 2016 -

Comments (5)

Category: Crime, Paranormal, 1970s

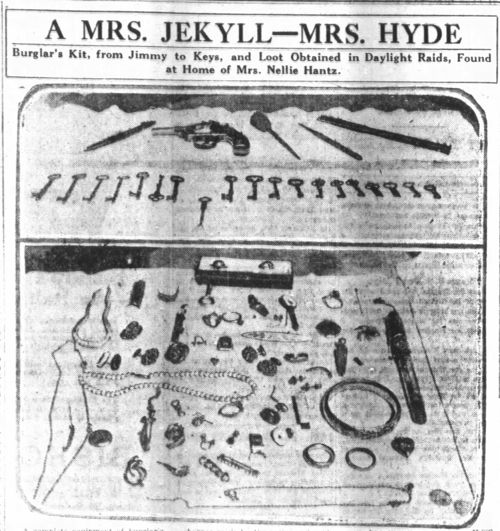

Nellie Hantz, housewife and thief

In October 1916, police arrested Mrs. Nellie Hantz and charged her with committing over 100 burglaries in the Chicago area. Her MO was unusual. When her husband, Carl, left in the morning to attend classes at a school of chemistry, and her 14-year-old daughter was at school, Nellie would sneak out and burglarize homes. She made sure to be home before her husband returned. The press named her the "wife thief" as well as the "matinee thief."She kept her loot and burglary tools hidden beneath the bedroom mattress, and her husband, upon her arrest, insisted he had no knowledge of her daytime activities. Nellie seconded this: "I've been prowling for eighteen months. I know you've been after me, but it took a long time to catch me, didn't it? I guess I was just born to be a crook. You'll have to lock me up. But it's too bad about Carl. He never suspected."

The burglary equipment police found beneath the mattress included "a revolver, a razor, a jimmy, an electric flash lamp, several files, and an ingenious set of keys, skeleton and otherwise, of her own manufacture."

Despite being caught, Nellie was unrepentant. She declared, "I love to rob places. I'd keep on being a burglar if I had a million, but I am afraid of the dark and I did all my robbing by daylight."

Coffeyville Daily Journal - Dec 6, 1916

Nellie Hantz - via nycmugshots

The Salem News - Oct 28, 1916

Chicago Daily Tribune - Oct 28, 1916

Posted By: Alex - Sat Oct 08, 2016 -

Comments (1)

Category: Crime, 1910s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |