Crime

Trial By Touch

Back in colonial times, the American legal system occasionally relied upon a curious form of murder investigation known as "Trial by Touch." The book Legal Executions in New England: A Comprehensive Reference offers this explanation:

That same book offers a number of examples of people found guilty by means of the Trial by Touch. For instance, in 1644 Goodwife Cornish of York, Maine, was accused of killing her husband, whose body was found floating in the York River:

Both of the accused were next brought before a council of local officials. The ensuing "trial" was a farce. The prosecution's only evidence was the result of the "Trial by Touch" and hearsay about the woman's character. It was her reputation more than anything else that counted against Goodwife Cornish. She was declared guilty and condemned to death. Edward Johnson was acquitted.

During her "trial" Goodwife Cornish continued to deny all knowledge of the murder. She repeated her admissions of lewd conduct and even named a local official as one of her lovers. Few doubted the story because the man had a reputation of his own. Goodwife Cornish was hanged at York in December of 1644. There the matter ended.

Trial by Touch was referred to by a number of different names, such as "Ordeal by Touch" or "Ordeal of the Bier." The Penny Magazine (January 1842) explains this latter name:

I haven't found much info in academic sources about the Trial by Touch. Evidently the custom was widely practiced throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and then brought to America by settlers. And apparently a bleeding corpse wasn't the only indicator of guilt. If the corpse seemed to change color, sweat, or move at all, that would be enough to convict the accused. In The Old Farmer and His Almanack (1920), GL Kittredge offers the example of the trial of Johan Norkott in England (1628):

The illustration at the top is by the Hungarian artist Mihály Zichy (1894). It depicts a scene from a ballad about a woman found guilty, by means of the Ordeal by Touch, of killing her young husband (via Hungarian Art History).

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jul 29, 2016 -

Comments (1)

Category: Crime, Customs, Death

The Yellowstone Zone of Death

Yellowstone National Park contains a 50-square mile "zone of death" where, legal scholars suggest, a person could commit murder without fear of prosecution. This zone is the part of the park that extends into Idaho.

The reason for this free-pass-for-murder lies with the Sixth Amendment which guarantees a defendant the right to a trial by a jury "of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed." The zone is in the State of Idaho, but because of the unique legal status of Yellowstone, it's in the judicial District of Wyoming. Therefore, to prosecute anyone a court would need to form a jury of people who live simultaneously in the State of Idaho and the District of Wyoming, and no one fits that bill because no one lives in the Idaho part of Yellowstone. Without being able to create a jury, a trial couldn't proceed.

A similar zone exists in the part of Yellowstone that extends into Montana. However, a few people live there, so a jury could, in theory, be formed from its residents.

This legal loophole was first pointed out in 2005 by Brian Kalt, a professor at Michigan State Law School, in an article published in the Georgetown Law Journal. Kalt urged Congress to pass legislation to fix the loophole before someone tested the loophole by committing murder in the death zone. The simplest fix, he proposed, would be to change the district lines so that the part of Yellowstone in Idaho would be included in the District of Idaho.

To date, Congress has not done anything to fix the problem. Part of the reason for this is political inertia. But there's also resistance to changing the District lines because this would place part of Yellowstone under the jurisdiction of the more liberal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which, it's feared, environmentalists could use to their advantage. So the "zone of death" remains.

The idea of a legal "zone of death" has naturally appealed to the imaginations of artists. The zone was featured in a best-selling mystery novel, Free Fire, by CJ Box. And in 2016 it became the subject of a film, Population Zero (trailer below).

More info: npr.org, bbc news, vox.com.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jul 24, 2016 -

Comments (8)

Category: Crime, Geography and Maps, Law

The Black Godfather

FINALLY, a figure who can soothe these divisive times!

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jul 20, 2016 -

Comments (3)

Category: Crime, Movies, Racism, Stereotypes and Cliches, 1970s

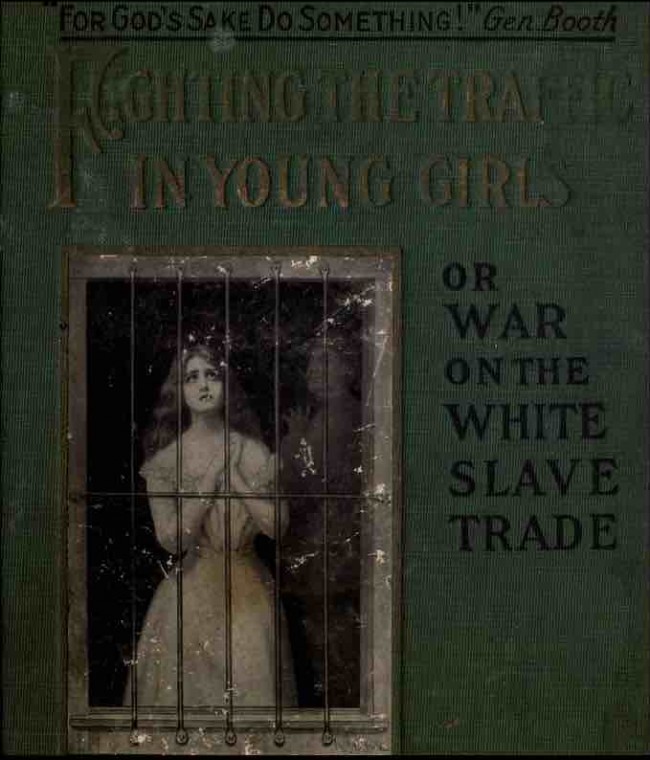

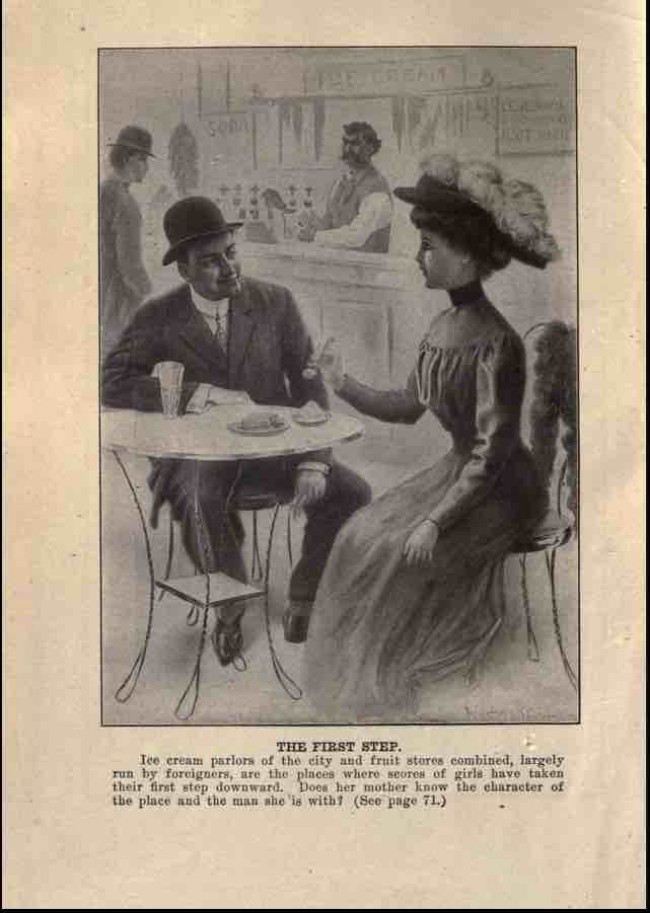

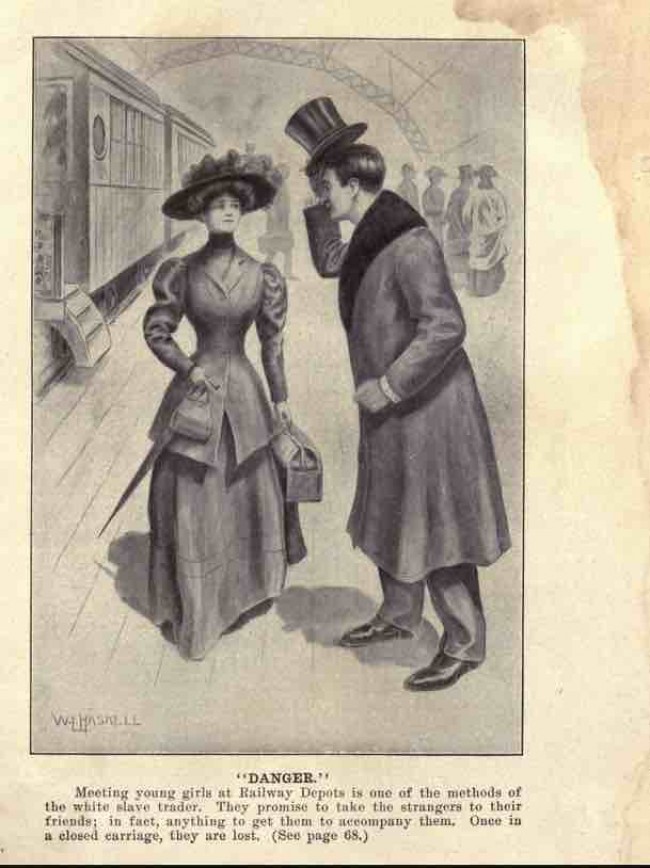

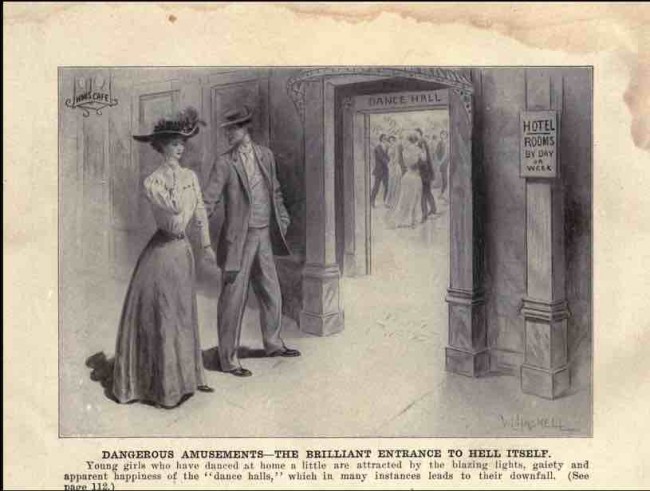

Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls

"Sex trafficking 2016," meet "white slavery 1910."Original text here.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jul 16, 2016 -

Comments (9)

Category: Crime, Sexuality, Public Indecency, The More Things Change, 1910s

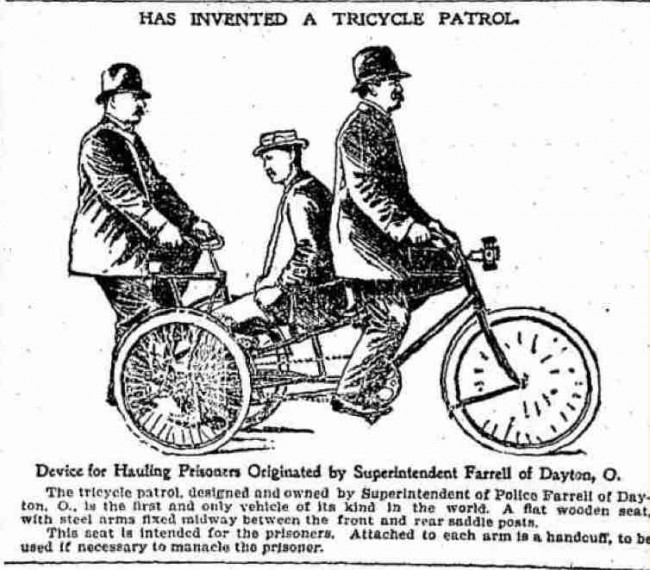

Tricycle Black Maria

Served the extra duty of public humiliation of criminal.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jul 11, 2016 -

Comments (3)

Category: Bicycles and Other Human-powered Vehicles, Cops, Crime, Inventions, Nineteenth Century

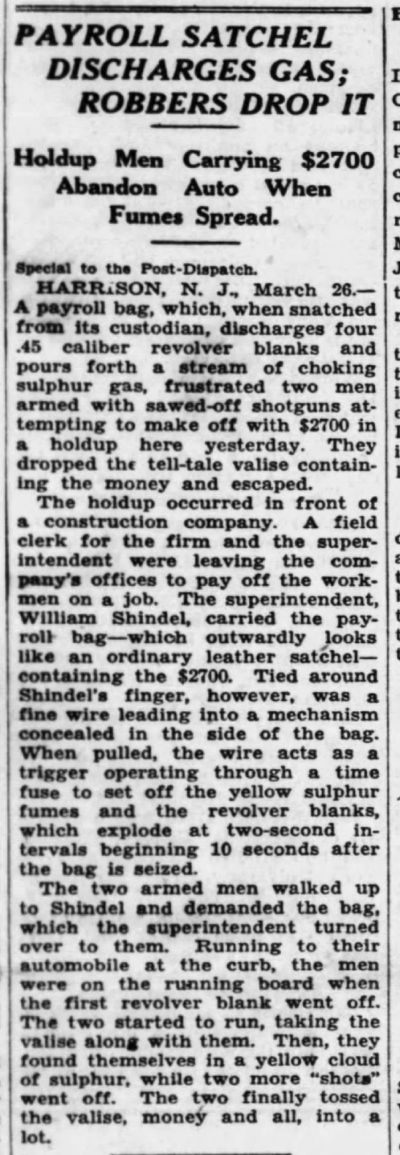

Trick Valise

March 1937: A tricked-out payroll satchel foiled would-be robbers. From Newsweek (Apr 3, 1937):Quite ingenious, but seems like it would work only once, since after that everyone would know what the trick was. So how did they protect the payroll subsequently?

Newsweek - Apr 3, 1937

St. Louis Post-Dispatch - Mar 26, 1937

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jun 18, 2016 -

Comments (5)

Category: Crime, Inventions, 1930s

Warning required before crime

January 1973: Texas State Rep. Jim Kaster filed a bill that would have required criminals to give their victims twenty-four hours notice before they committed a crime. Argued Kaster, "Obviously the criminal is not going to do it, but this would be another punishment that could be added to the penalty." No surprise, the bill was defeated.

Arizona Republic - Jan 19, 1973

And this article gives a little more info:

El Paso Herald-Post - Jan 19, 1973

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jun 11, 2016 -

Comments (10)

Category: Crime, Law, 1970s

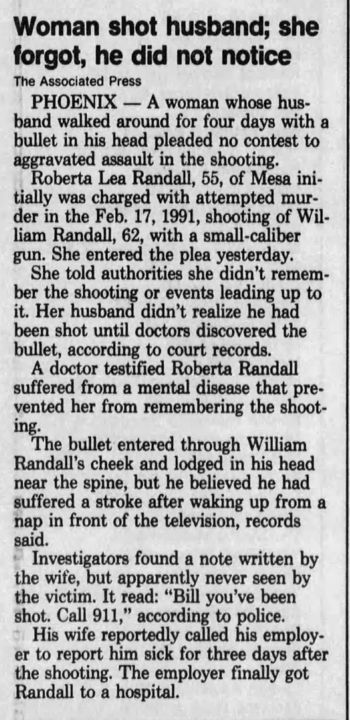

Forgot she shot him

The strange case of Roberta and William Randall of Phoenix, Arizona. She shot him in the face while he was napping, then forgot she shot him. He didn't realize he had been shot. Apparently the hole in his cheek didn't make him suspicious. Nor did the note she had written for him, "Bill, you've been shot. Call 911."

Democrat and Chronicle - Feb 27, 1992

The Arizona Republic (Mar 17, 1991) offers a few more details about this mysterious case:

Posted By: Alex - Tue May 31, 2016 -

Comments (8)

Category: Crime, 1990s

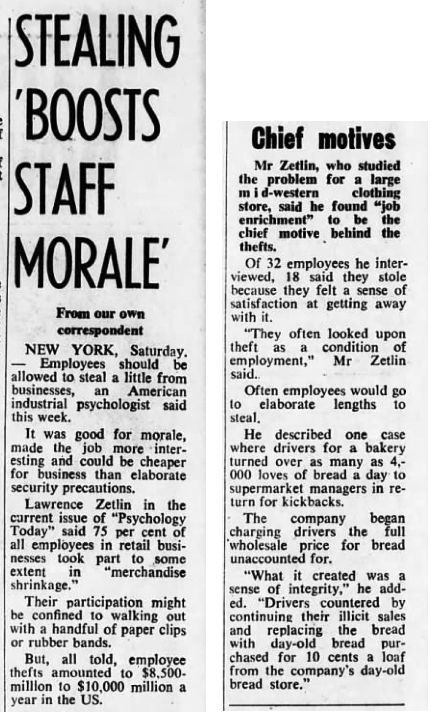

Stealing Boosts Staff Morale

Companies do all kinds of things to boost staff morale. They hire motivational speakers, have team-building exercises, give employees gifts, etc.But the industrial psychologist Lawrence Zeitlin, in an article published in June 1971 in Psychology Today ("A little larceny can do a lot for employee morale"), argued that the most effective way a business could boost morale was by allowing its employees to steal a little from the company.

He argued that theft added to a sense of "job enrichment" by making the job more interesting. It gave employees a sense of satisfaction at getting away with it. Also, workers "often looked upon theft as a condition of employment." Furthermore, he noted, allowing the theft could be cheaper than installing elaborate security precautions.

In her book Management and Ideology, business author Judith Merkle provides some background info on Zeitlin's article:

Sydney Morning Herald - May 30, 1971

Posted By: Alex - Wed May 25, 2016 -

Comments (6)

Category: Business, Crime, 1970s

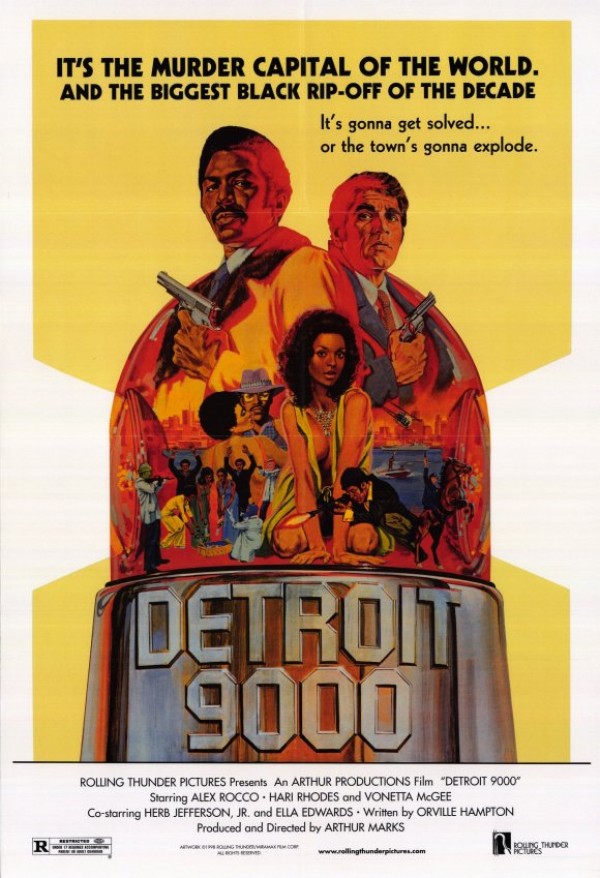

Detroit 9000

Posted By: Paul - Fri Apr 29, 2016 -

Comments (6)

Category: Crime, Movies, Stereotypes and Cliches, 1970s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |