Death

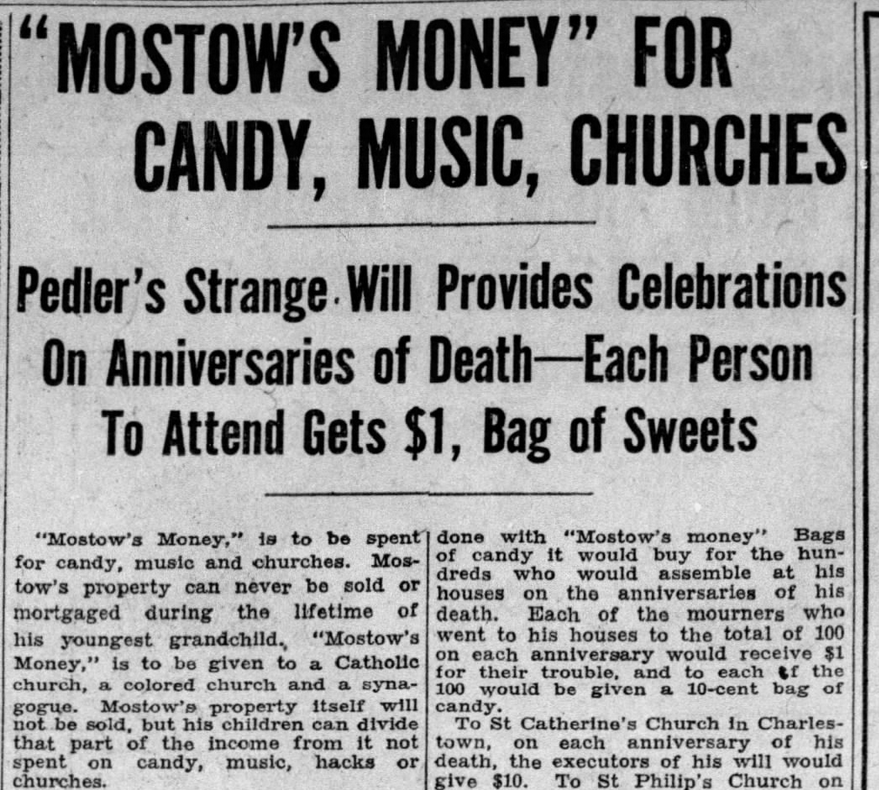

The Strange Will of John Mostow

Source: The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts)04 Apr 1928, Wed Page 16

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jul 06, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Eccentrics, Law, Money, Candy, 1920s

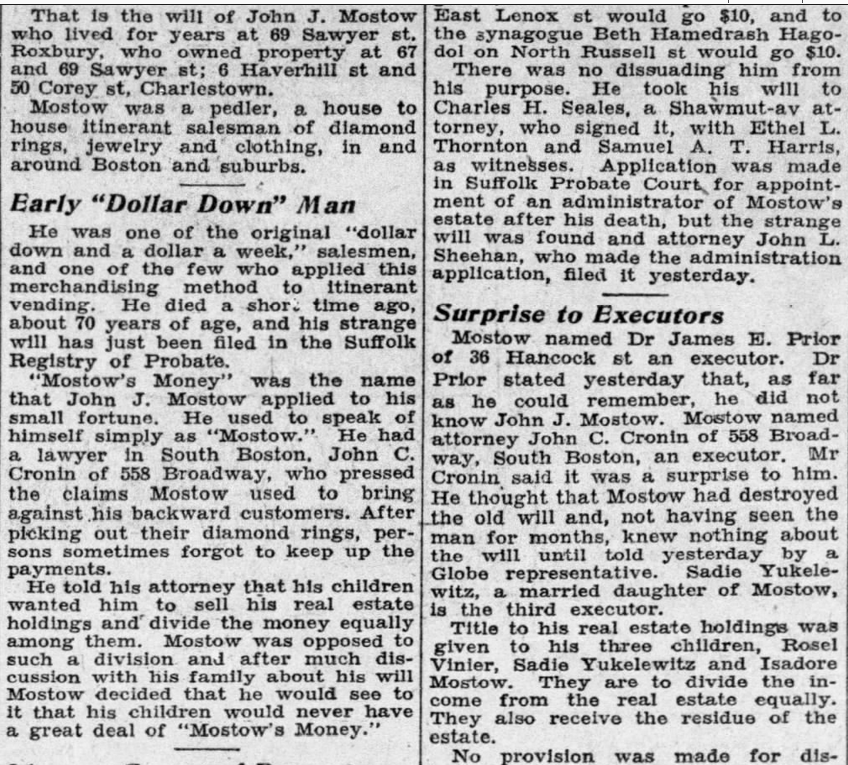

“Why’d It Have To Be Snakes?”

Source: The Pomona Daily Review (Pomona, California) 10 Jul 1913, Thu Page 4

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jun 28, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Death, Reptiles, Snakes, Worms and Other Slithery Things, 1910s, Middle East

Heart Attack Fells Winner

Mar 1972: Overwhelmed by the excitement of winning on a game show, housewife Maud Walker had a heart attack and died in front of the cameras. The studio didn't air that episode but offered to show it to her relatives so they could "see how happy she was."

Wilmington News Journal - Mar 8, 1972

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jun 23, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Death, Television, 1970s

The Burial of Sandra Ilene West

May 1977: Per her request, oil heiress Sandra Ilene West was buried dressed in a lace night gown, seated in her 1964 blue Ferrari "with the seat slanted comfortably".More info: Retro Hollywood

Christie's Auction Catalogue 1979

Fort Worth Star-Telegram - May 20, 1977

Jet - July 7, 1977

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jun 20, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, 1970s, Cars

Follies of the Madmen #535

Source. (Page 19)

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jun 14, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Death, Advertising, Soda, Pop, Soft Drinks and other Non-Alcoholic Beverages, 1910s

Desairology

Noella Charest-Papagno coined the term 'desairology' to mean doing hairstyling and cosmetics for the deceased. She created the word by combining 'des' (for deceased), 'air' (for hair), and 'ology' (a branch of learning). She thought the term sounded better than 'necrocosmetologist,' which had previously been the job title for funeral hairdressers. Her term seems to have caught on within the profession. At least, it has a wikipedia page.In 1980, Papagno also authored the first book on hairdressing for the dead — Desairology: The Dressing of Decedent's Hair.

She created the somewhat bizarre video below around 2015. It's titled, "Dead lady speaks. Looks better now."

More info: JJ Publishing Group

Fort Lauderdale News - Apr 27, 1986

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jun 10, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Hair and Hairstyling

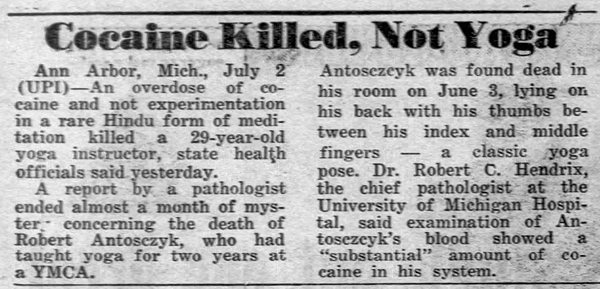

Death By Yoga?

Robert Antoszczyk died on June 3, 1975. That much everyone agrees on. But how he died is more controversial.

Robert Antoszczyk

Initial reports claimed that he went into a yogic trance and projected his spirit out of his body, but that he didn't know how to re-enter his body. So he died. This explanation remains popular with the Fortean crowd.

The official explanation, which emerged later, is that he died from a cocaine overdose. However, his friends and family always contested this, insisting that he was very much into clean living and never drank, let alone took drugs.

Over at medium.com, Nick Ripatrazone has an article in which he explores this case, as well as the broader interest in 'astral projection' during the 1970s.

Palladium Item - June 30, 1975

NY Daily News - July 3, 1975

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jun 03, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Forteana, Paranormal, 1970s

German Rocket Car

First attempt: OK. Second attempt: not so much. The way they are covering up the car with a tarp at the end does not bode well for the fate of the driver.The relevant Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jun 01, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Death, Destruction, Inventions, 1920s, Europe, Cars

The Loved One Launcher

Starting at $375.00 from CremationSolutions.com.

They should next come out with a catapult model for non-cremated loved ones.

via Dave Barry

Posted By: Alex - Sun May 08, 2022 -

Comments (6)

Category: Death

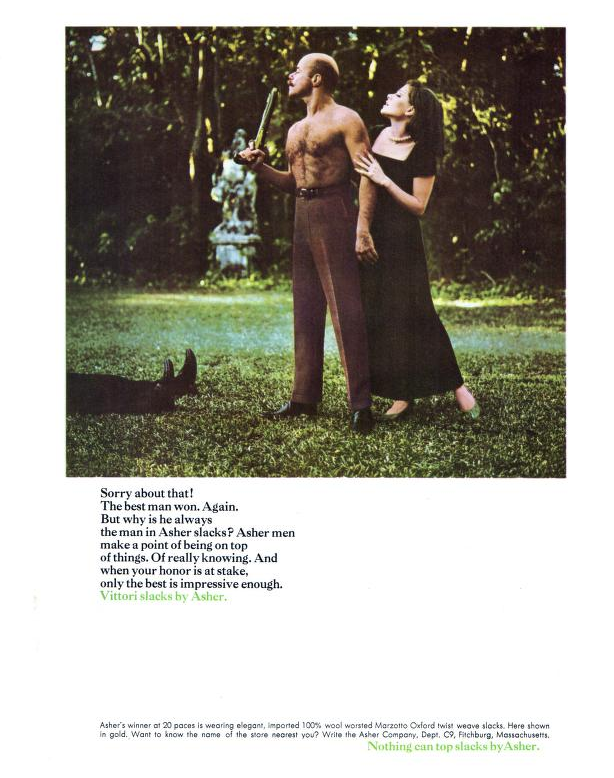

Follies of the Madmen #531

"Our pants are endorsed by shirtless murderers."

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Fri May 06, 2022 -

Comments (8)

Category: Death, Fashion, Advertising, 1960s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |