Experiments

The Mighty Powers of Hagfish Slime

My high-school pal Sherry Mowbray, who grew up to be a top-flight biologist, points me with glee to this video illustrating how powerful is the slime secreted by the awesome hagfish.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Sep 10, 2008 -

Comments (11)

Category: Animals, Science, Experiments, Body Fluids

One Touch of Homer Makes the Whole World Kin

After briefly distracting the patients, the researchers then asked them to think about the clips for a minute and to report “what comes to mind.” The patients remembered almost all of the clips. And when they recalled a specific one — say, a clip of Homer Simpson — the same cells that had been active during the Homer clip reignited. In fact, the cells became active a second or two before people were conscious of the memory, which signaled to researchers the memory to come.

Why is Homer Simpson singled out as the test case? Obviously because the human brain has specific neurons that emulate or actually induce and compel Homer-Simpson-style behavior.

And there in a nutshell you have the whole basis for ninety-nine percent of the contents of WEIRD UNIVERSE.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Sep 05, 2008 -

Comments (13)

Category: Celebrities, Science, Experiments, Psychology, Stupidity, Television, Husbands, Cartoons

Help Zimbardo Study Helping

Dr. Phil Zimbardo, famous for conducting the Stanford Prison Experiment which revealed how quickly average college students will embrace the roles of sadistic prison guards and passive prisoners, and most recently author of The Lucifer Effect, is now turning his attention to helping behavior. From the hero workshop blog (via boing boing):The first step is to conduct a survey with as many participants as possible. That’s where you come in. The survey takes about 30 minutes and can be found at www.socialpsychresearch.org.

I took one look at the length of time and thought, "30 minutes! I don't want to take a survey for that long!" I'm basically unhelpul and selfish. But this made me realize that the only people taking the survey will be those that are more helpful than most. It'll be a biased sample.

Zimbardo and his co-researchers are very smart people, so I'm sure they realize this. I'm guessing that the real purpose of the survey may be to find out how many people actually take it, versus how many visit the link. That could provide a quick snapshot of how many helpful people there are on the internet. (Thanks to Joe Littrell!)

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 27, 2008 -

Comments (1)

Category: Science, Experiments, Psychology

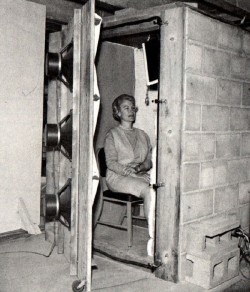

Sonic Boom Simulation Chamber

During the 1960s NASA sponsored research into the effect of sonic booms on human subjects. This was in response to growing concern about "the nature of the boom phenomena" as supersonic aircraft were flying with increasing frequency. Shown in the picture is one subject (unidentified) about to be locked inside the "Sonic Boom Simulation Chamber."I like the juxtaposition of the prim-and-proper woman and the massive audio system. Unfortunately there aren't any pictures of what she looked like after being repeatedly blasted with simulated sonic booms.

The image comes from NASA Contractor Report CR-1192, "Relative Annoyance and Loudness Judgments of Various Simulated Sonic Boom Waveforms."

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 20, 2008 -

Comments (2)

Category: Science, Experiments, Technology

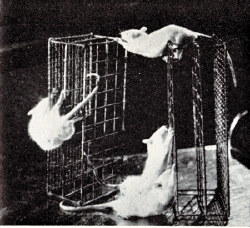

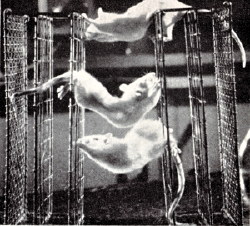

Catatonic Rats

Old science books and articles are a great source of weird images. For instance, I found the two pictures below in Of Mice, Men and Molecules by John Heller (published in 1960). The images are titled "Catatonic rats" and have this explanatory caption:Unfortunately, Heller doesn't reveal what the chemical is that caused the rats to freeze in these positions. My guess is that it's LSD.

|  |

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 18, 2008 -

Comments (3)

Category: Animals, Drugs, Science, Experiments

The Smoke-Filled Room

If you were sitting in a waiting room and smoke began to billow out of a vent in the wall, you'd probably do something about it. At least, you'd report the problem to someone. Or maybe not.In a famous experiment conducted by John Darley and Bibb Latané during the 1960s, Columbia University students were invited to share their views about problems of urban life. Those who expressed an interest in participating were asked to first report to a waiting room in one of the university buildings where they would find some forms to fill out before being interviewed. They had no idea that the urban-life study was just a cover story. The real experiment occurred in the waiting room.

As they filled out the forms, smoke began to enter the room through a small vent in the wall. By the end of four minutes, there was enough smoke to obscure vision and interfere with breathing. Darley and Latané examined how the students reacted to this smoke in two different conditions.

In the first condition, the students were alone. When this was the case, they invariably investigated the smoke more closely and then went out into the hallway to tell someone about it.

But in the second condition, the students were not alone. There were two or three other people in the room, who were secret confederates of the researchers. They had been instructed to not react to the smoke. They would look up at it, stare briefly, shrug their shoulders, and continue working on the forms. If asked about it, they would simply say, "I dunno."

In this setting, according to Darley and Latané, "only one of the ten subjects... reported the smoke. the other nine subjects stayed in the waiting room for the full six minutes while it continued to fill up with smoke, doggedly working on their questionnaires and waving the fumes away from their faces. They coughed, rubbed their eyes, and opened the window -- but they did not report the smoke."

That's the power of group pressure.

If you ever get the chance, check out Darley and Latané's book The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn't He Help? It's not easy to find because it's out of print, but it's full of strange experiments like the smoke-filled room one.

Also check out this youtube video based on the smoke-filled room experiment. It's not the original study, but a later replication of it.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Aug 14, 2008 -

Comments (0)

Category: Science, Experiments, Psychology

Dogs Catch Human Yawns

I imagine that many dog owners have noticed that dogs can "catch" yawns from humans, and vice versa (I think). So was an experiment to verify this really necessary? The animal behaviorists at the University of London evidently thought so. In their defense, I'd argue that just because something seems obvious, it still might yield interesting results when examined under controlled conditions in a laboratory setting. From the Aug 2008 issue of Biology Letters:The BBC has a video of a yawning dog -- making me sleepy! (Thanks, Sandy!)

Posted By: Alex - Sun Aug 10, 2008 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Experiments

Bizzare Experiments

But eagle-eyed reader Rowenna noticed that, on the cover, the word "bizarre" was misspelled. They spelled it "bizzare". Panicked, I ran to check if the actual cover had the same misspelling. (By coincidence, I had just received my copy of the UK edition in the mail.) Thankfully, it was spelled correctly. But then I noticed that the same misspelling occurs on the cover photo on Amazon. I'll have to let my publisher know. I don't think "bizzare" is an alternative UK spelling of "bizarre".

Posted By: Alex - Thu Aug 07, 2008 -

Comments (1)

Category: Science, Experiments, Books, Alex

The Shoelace Experiment

Norbert Elias (1897-1990) was a highly influential sociologist, best known for his two-volume work The Civilizing Process. Among his less well-known accomplishments was his shoelace experiment.

In 1965 and 1966 Elias traveled throughout Europe as a tourist. Deciding to mix sociological research with pleasure, he resolved to find out how people in different countries would respond to him if he left his shoelaces untied. Ingo Moerth summarized the results of this experiment in the June 2007 issue of The Newsletter of the Norbert Elias Foundation:

(2) England - London 1965 (Regent Street, Bond Street): Here Elias conducted three experiments, all of which lasted three hours. He got nine reactions, mostly by older ‘citizens’, as Norbert Elias notes: ‘In England mostly elderly gentlemen reacted by communicating with me on the danger of stumbling and falling’ (in Elias 1967, as translated by Ingo Moerth). This might be interpreted as an established ‘society-context’, where the anonymity is overruled by engaged and experienced citizens watching the public space.

(3) France - Paris 1966 (Champs Elyseés, Boulevard St Michel, Montparnasse): Here Elias conducted three experiments of three hours, but with much less reaction. Only two people communicated directly with him about the visible shoe-lace problem, both sitting in street cafés on the Champs Elyseés, besides a youngster who shouted directly ‘prenez garde’ (‘take care’) into his ear, much to the amusement of the young man’s group of companions. As an explanation of this different reaction, perhaps a different character of ‘public space’ in France may be relevant: mere observation in contrast with engagement and direct intervention, as in London/UK or in Germany (see the following discussion, as cited below).

(4) Germany - for instance Münster 1965: Here the ‘society-context’ mentioned above was – according to Norbert Elias – watched and communicated not by gentlemen, but mostly by women: ‘In Germany older men only looked at me somewhat contemptuously, whereas women reacted directly and tried to ‘clean up’ the obvious disorder, in the tramway as well as elsewhere. Here in most cases a short conversation, comprising more than the obvious ‘shoe-lace disorder’ took place, such as a short warning about what might happen if I didn’t take care of the basic problem’ (in Elias 1967, as translated by Ingo Moerth).

(5) Switzerland: Bern 1966: Here Elias experienced the most elaborate conversation about dangers related to untied shoe-laces, including admonitions about dangers of eating grapes and using trains. He explicitly states: ‘This was probably an exception, from which no conclusion on a Swiss national character can be drawn' (in Elias 1967, as translated by Ingo Moerth).

It would be interesting to conduct this experiment in America. New Yorkers would probably ignore you. In Los Angeles everyone drives, so you'd be lucky if you encountered another pedestrian.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 06, 2008 -

Comments (0)

Category: Fashion, Experiments, Psychology

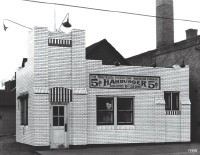

The White Castle Experiment

However, the idea of conducting a fast-food diet experiment wasn't original to Spurlock. That honor goes to Jesse McClendon, a researcher at the University of Minnesota, who in 1930 fed a volunteer a diet of only White Castle hamburgers for 13 weeks. From the U of M Medical Bulletin:

A willing subject presented himself: Bernard Flesche, a U of M medical student working his way through school. Flesche kept a diary during the ordeal. "He started out very enthusiastic about eating 10 burgers at a sitting," notes his daughter, Deirdre Flesche, "but a couple of weeks into it, he was losing his enthusiasm." His sister frequently tried to tempt him with fresh vegetables, but Flesche allowed nothing but White Castle Slyders™ to pass his lips.

Flesche survived his ordeal without developing any significant health problems. The owner of White Castle interpreted this to mean that a hamburger diet is healthy and heavily promoted the experiment in advertisements. Flesche, however, who had once been a hamburger lover, developed a permanent aversion to them. He never willingly ate a hamburger again.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 04, 2008 -

Comments (0)

Category: Food, Experiments, 1930s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |