Category:

Experiments

Experiments

Testing the Law of Probability

Pope R. Hill, a professor at the University of Georgia during the 1930s, wanted to find out. But he thought coin-flipping was too imprecise a measurement, since any one coin might be imbalanced, causing it to favor heads or tails.

Instead, he filled a can with 200 pennies. Half were dated 1919, half dated 1920. He shook up the can, withdrew a coin, and recorded its date. Then he returned the coin to the can. He repeated this procedure 100,000 times!

Of the 100,000 draws, 50,145 came out 1920. 49,855 came out 1919. Hill concluded that the law of half and half does work out in practice.

If you have absolutely nothing better to do, you can head over to Random.org, which hosts a virtual coin toss, and try to outdo Hill by clicking the "flip coin" button 100,001 times. Make sure to record your results. Although I doubt a virtual coin toss would be considered truly random, even though random.org claims their randomness "comes from atmospheric noise, which for many purposes is better than the pseudo-random number algorithms typically used in computer programs."

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jul 24, 2008 -

Comments (0)

Category: Experiments, 1930s

The Cow Whisperer

I suspect cows are going to become a theme here at WU. They're ubiquitous and silly and important. Those are three good criteria for inclusion here. Hey, if cows were good enough for Gary Larson humor, they're good enough for us!The latest news is that they're demanding headphones as they graze! Not sure if iPods are included. Read the article here.

Then watch the video of "The Cow Whisperer" here.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jul 23, 2008 -

Comments (5)

Category: Agriculture, Food, Science, Experiments, Technology, Cows

Smelly Old People

Do old people produce an unpleasant body odor? In 2001 Japanese researchers conducted an experiment that suggested they do. The researchers had a group of volunteers sleep in the same t-shirt for three nights. According to the New Scientist:

The researchers then studied the volatile chemicals picked up by the material. Volunteers over 40 produced an unsaturated aldehyde called 2-nonenal, which the team described as having an unpleasant "greasy" smell.

Happily, the case against gramps is not yet proven. Recently researchers at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia conducted similar studies, but detected no unpleasant smells coming from old folks. They suggested the foul odor found in the Japanese study may have been produced by a diet high in fish.

Whether or not the phenomenon of "aging odor" is real (I doubt it), I can't believe the cosmetics industry hasn't picked up on this idea and tried to profit from it. They could come up with a scary, scientific-sounding name for age-related odor (what about Geritosis?), and then roll out a line of products supposedly specially formulated to combat it. With the graying of the baby boomers, they would make a killing.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jul 22, 2008 -

Comments (2)

Category: Experiments

What do women look at?

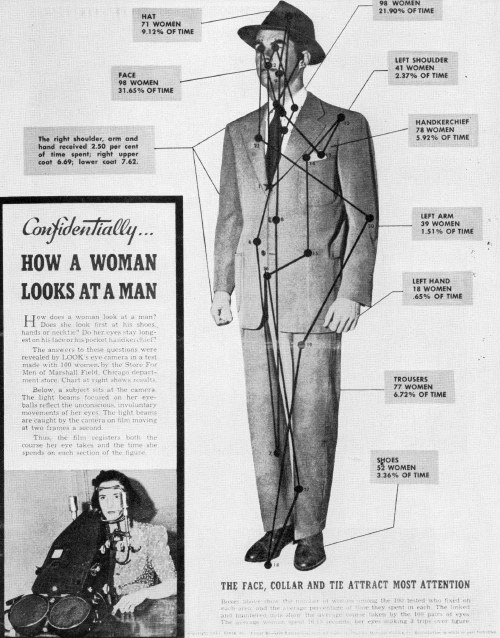

One of the earliest eyetracking studies was conducted by the Visual Research Laboratories at Drake University during the 1940s. They used light beams to follow the eyeball movements of women shown a picture of a man. The subjects were all customers at the Marshall Field department store in Chicago. Check out this diagram they produced titled "How a Woman Looks at a Man" (from Look magazine, 1944).

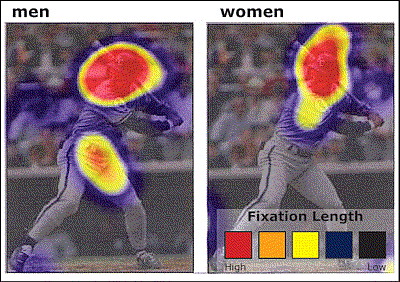

An eyetracking study conducted in 2005 by the Nielsen/Norman Group (described in Online Journalism Review) produced similar results. When shown a photo of baseball-player George Brett, womens' eyes focused on his face. By contrast, when men were shown the same photo, they focused also on his crotch. The researchers noted, "Men tend to fixate more on areas of private anatomy on animals as well, as evidenced when users were directed to browse the American Kennel Club site." (This is one of those factoids that doesn't make me feel proud to be a man.)

But what about less tame material? Of course, science has explored this area as well. A 2007 study funded by the Center for Behavioral Neuroscience analyzed the viewing patterns of men and women shown sexual photographs. Strangely enough, the viewing patterns were not the same as in the earlier studies. From Science Daily:

Researchers hypothesized women would look at faces and men at genitals, but, surprisingly, they found men are more likely than women to first look at a woman's face before other parts of the body, and women focused longer on photographs of men performing sexual acts with women than did the males...

"The eye-tracking data suggested what women paid most attention to was dependent upon their hormonal state. Women using hormonal contraceptives looked more at the genitals, while women who were not using hormonal contraceptives paid more attention to contextual elements of the photographs," Rupp said.

"The eye-tracking data suggested what women paid most attention to was dependent upon their hormonal state. Women using hormonal contraceptives looked more at the genitals, while women who were not using hormonal contraceptives paid more attention to contextual elements of the photographs," Rupp said.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jul 14, 2008 -

Comments (0)

Category: Sexuality, Experiments

Pavlovian Fish

Ivan Pavlov famously conditioned dogs to salivate every time they heard a dinner bell. The U.S. Army hopes to use a similar technique to train fish in Buzzards Bay off the coast of Massachusetts. According to the Cape Cod Times, the experiment:houses 5,000 juvenile black sea bass in a dome-shaped structure at the bottom of Buzzards Bay, for the purpose of feeding them after playing a 280 Hz tone. The study is being led by Scott Lindell, director of MBL's Scientific Aquaculture Program, to determine whether the caged fish — once accustomed to the tone then released into the wild — will return to the dome for recapture when the tone is played. The hope is to create a less harmful way to fish or better replenish natural fish stock, project officials told the Times in March.

The experiment has raised concerns among a consumer advocacy group, who are suing the Army, but that's not what interests me. What interests me is whether the fish salivate when they hear the tone. Do fish, in fact, have salivary glands? An answer from genuineideas.com:

Although the most well developed glands are found in mammals, many other vertebrates and invertebrates have salivary glands. Fish and other aquatic animals clearly do not lack opportunities to add water to their meals; hence most aquatic animals are devoid of "true" salivary glands. However, some form of lubrication is still necessary to assist swallowing even in water, and this is provided by mucous glands along the tongue and roof of mouth (Mucous secretion is present in all animals.)

And that's your weird fish fact of the day.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jul 13, 2008 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Experiments

A Month of Spam

McAfee recently released the results of its S.P.A.M. experiment, which stands for "Spammed Persistently All Month." Fifty subjects volunteered to expose themselves to a month of intensive spamming.When I first noticed this headline, I imagined some kind of Ludovician Aversion Therapy experiment -- subjects strapped into chairs, eyes taped open, forced to view endless screens of spam until they started drooling and screaming for it to stop.

Unfortunately, the experiment wasn't that colorful. Instead, the subjects were simply "given permission to go where most Internet users would not dare, in order to discover how much spam they would attract and what the effects would be." I'm guessing this means they signed up with AOL.

The result: "the participants from 10 countries received more than 104,000 spam e-mails throughout the course of the experiment. That's 2,096 messages each - the equivalent of approximately 70 messages a day."

That surprised me. I thought they'd get a LOT more spam. I estimate my spam filter traps at least 70 messages a day, and I'm not trying to get the stuff like they were.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jul 09, 2008 -

Comments (0)

Category: Advertising, Experiments

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |