Experiments

The Great Starvation Experiment, 1944-1945

I wrote this brief article a number of years ago. It used to be posted on another site, which no longer exists. So I'm relocating it here. . .One of the greatest killers of World War II wasn't bombs or bullets, but hunger. As the conflict raged on, destroying crops and disrupting supply lines, millions starved. During the Siege of Leningrad alone, over a thousand people a day died from lack of food. But starvation also occurred in a more unlikely place: Minneapolis, Minnesota. It was here that, in 1945, thirty-six men participated in a starvation experiment conducted by Dr. Ancel Keys.

Group photo of the participants

Dr. Ancel Keys

The starvation experiment developed out of Keys' interest in nutrition. He realized that although millions of people in Europe were suffering from famine, there was little doctors could do to help them once the war was over, because almost no scientific information existed about the physiological effects of starvation. Keys convinced the military that a study of starvation could yield information that would have both humanitarian and practical benefits — because knowing the best rehabilitation methods could ensure the health of the population and thereby help democracy grow in Europe after the war. Having secured his funding, Keys set out on his novel experiment.

More in extended >>

Posted By: Alex - Tue Mar 07, 2023 -

Comments (5)

Category: Experiments, Nutrition, 1940s, Dieting and Weight Loss

The taste of food in dark isolation

Beatrice Finkelstein, a nutrition researcher at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, conducted a series of "dark-isolation studies" during the 1950s. Subjects were placed for periods of 6 to 72 hours in a totally dark, sound proof chamber furnished with a bed, chair, refrigerator, and chemical toilet.

The purpose of this was to find out how astronauts might react to being confined in a small, dark space for a prolonged period of time. And in particular how their responses to food might change.

Some of her results:

But the stranger result was how the lack of visual input completely changed the flavor of the food:

More info: "Feeding crews in air vehicles of the future"

Beatrice Finkelstein (source)

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jan 30, 2023 -

Comments (4)

Category: Food, Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, Experiments, Psychology

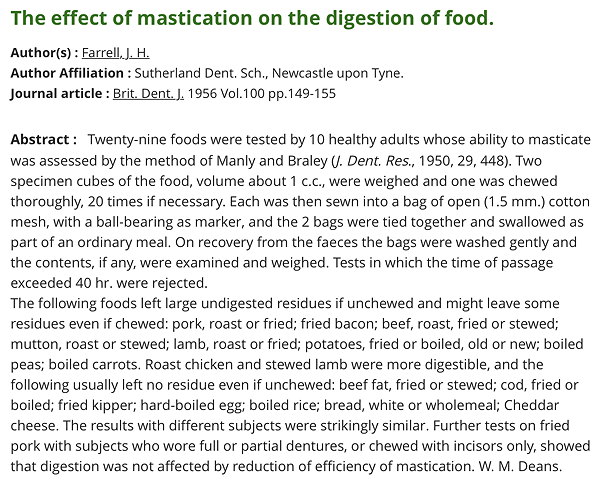

How much do you need to chew your food?

British dentist John H. Farrell spent much of his career studying the relationship between chewing and digestion. This involved repeated experiments in which he put bits of food in small, cotton-mesh bags, had subjects chew the food (or not), and then swallow it. The next step was more unpleasant:The years he spent doing this convinced him that "very little chewing is required for maximum digestion."

More info: "The effect on digestibility of methods commonly used to increase the tenderness of lean meat"

Bedford Times-Mail - Apr 17, 1964

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 21, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Food, Experiments, Stomach, Teeth

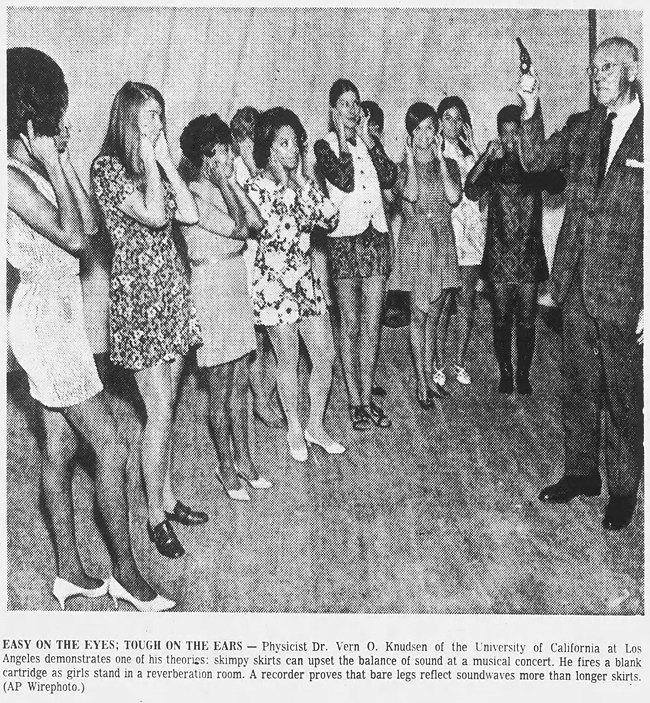

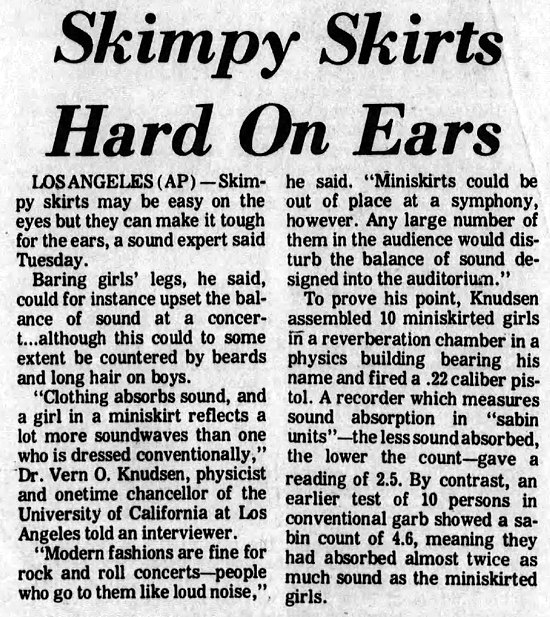

The Acoustics of Miniskirts

October 1969: UCLA Professor Vern O. Knudsen assembled ten young women wearing miniskirts in a reverberation chamber and fired a blank cartridge from a pistol. He did this to prove his hypothesis that bare legs revealed by a miniskirt will reflect more sound than legs covered by a long skirt.His hypothesis confirmed, he warned that miniskirt wearers might disturb the carefully engineered balance of sound in concert halls by reflecting more sound. He noted: "We must be acoustically thankful that they don't wear bikinis."

Rock Island Argus - Oct 29, 1969

Orangeburg Times and Democrat - Oct 29, 1969

Oddly enough, this wasn't the first time a scientist had warned of the acoustic danger of short skirts. Back in 1929, Colgate University Professor Donald A. Laird had issued a very similar warning: "He quoted scientific reports to prove that shortening of women's skirts has added to noise by removing some sound deadening surface."

San Bernardino County Sun - July 4, 1929

Related posts: Miniskirts for road safety, Nun in a miniskirt

Posted By: Alex - Thu Nov 03, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Fashion, Science, Experiments, 1960s, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

The Palatibility of Tadpoles

In 1970, biologist Richard Wassersug conducted a study to determine what different kinds of tadpoles taste like. More specifically, whether some taste worse than others. He convinced 11 grad students to be his tadpole tasters.The most distasteful tadpole was Bufo marinus, while the most palatable ones were Smilisca sordida and Colostethus nubicola.

This confirmed his hypothesis that the most visible tadpoles were the least palatable. Their bad taste deterred predators from eating them, whereas the better tasting tadpoles relied on concealment to avoid being eaten.

Thirty years later, Wassersug was awarded an Ig Nobel Prize for this research.

More info: "On the Comparative Palatibility of Some Dry-Season Tadpoles from Costa Rica"

Richard Wassersug poses with a frog

image source: University of Chicago

Posted By: Alex - Thu Sep 29, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Science, Experiments

Bulletproof Ointment

1915: Inventor Percy Terry of Los Angeles believed that he had perfected an ointment that would toughen the skin so much that it would become bulletproof. He envisioned "an army of bulletproof men who could advance with immunity against anything less than cannon."He decided to test the ointment on himself. After rubbing it into his skin for several weeks, he shot himself in the face. Turned out, he wasn't bulletproof. He died at the County Hospital.

Los Angeles Times - Aug 30, 1915

Posted By: Alex - Sat Aug 20, 2022 -

Comments (5)

Category: Death, Experiments, 1910s, Weapons

Hydrox Fecalis

In order to advance medical knowledge, Dr. Stephen Sulkes and a handful of volunteers ate Hydrox cookies and later checked to see if their poop had turned black. It had. They named this phenomenon 'Hydrox Fecalis.' Their results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine (Jan 5, 1984). Reproduced below:The presence of dark stools can be a cause of consternation to the patient and is made more anxiety-producing when accompanied by abdominal pain or other discomfort. The causes of melena are well outlined in several reviews, along with the usual non-heme causes of black stools, including iron, bismuth, charcoal, licorice, and certain fruits.

To this list should be added the colorings present in chocolate sandwich cookies. In several independent tests (with myself and several volunteers as experimental subjects), the presence of black stools approximately 18 to 24 hours after ingestion of 225 to 450 g of chocolate sandwich cookies has been observed. Variation in brand of cookie did not change the stool character. Testing with other types of cookie (oatmeal, peanut butter, and chocolate chip, among others) has not resulted in the same stool findings, although abdominal pain or nausea or both appear to be equally frequent associations.

This phenomenon may be on the increase because of shifts in U.S. dietary habits, so elicitation of a good dietary history in cases of black stools and abdominal pain should be pursued. Inasmuch as "cookie-induced pseudomelena" is both unprofessional sounding and too appropriately descriptive, a suggested name for this entity is "Hydrox fecalis."

Stephen Sulkes, M.D.

Monroe Developmental Disabilities

Rochester, N.Y.

Someone needs to repeat the experiment with Oreo cookies.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Aug 16, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Experiments, Junk Food, Excrement

The Pressed Frog Phenomenon

I found the image below at the Texas History site of the University of North Texas. It appears there as is, without any further explanation (or date).

I realize that the indentations on top of bricks are called 'frogs', but why were actual frogs being placed inside bricks?

As far as I can tell, it must have been an experimental demonstration of the 'pressed frog phenomenon' — this phenomenon being that one can place a living frog inside a brick as its being made, apply thousands of pounds of pressure to the brick to mold it, and the frog will survive. The frog won't be happy about the experience, but it won't burst. Whereas the same pressure applied to a frog that isn't in a brick will definitely cause it to burst.

Obviously the brick hasn't been heated in a kiln, because that would definitely cook the frog.

The article below from 1925 explains the science of why a frog in a brick doesn't burst. The key part of the (overly long) explanation is this sentence:

However, this doesn't solve the mystery of who first decided to put a frog in a brick.

Clarion Ledger Sun - Aug 16, 1925

Posted By: Alex - Mon May 23, 2022 -

Comments (5)

Category: Animals, Science, Experiments, 1920s

Knives made from frozen human feces

The non-fiction book Shadows in the Sun by Wade Davis contains the following passage:This caught the attention of some archaeologists who decided to test if a knife made from human feces would actually be strong enough to cut through muscle and tendons. They published their results in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

The researchers paid close attention to detail. For instance:

However, the results were disappointing: "the knife-edge simply melted upon contact, leaving streaks of fecal matter."

Conclusion: the story of the fecal knife was an urban legend.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Mar 25, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Science, Experiments, Excrement

The Case of the Furious Children

In 1954, six young boys who exhibited violent behavior were brought to live on the grounds of the National Institute of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. They were specifically selected because they were deemed the worst of the worst:For the next five years, the boys were attended around the clock by a team of specialists.

It was all part of an experiment, which came to be known as the "Case of the Furious Children," designed to find out why these young boys were so violent and whether they could be turned into responsible citizens. Eventually, around $1.5 million (in 1950's dollars) was spent on this effort.

By the end of the experiment, one of the researchers, Dr. Nicholas Long, said that the boys now had a "better than 50-50 chance of living a productive life." So what became of them? Were they reformed, or did they head down the path of crime and prison that they originally seemed to be destined for?

I'd be interesting to know, but I haven't been able to find anything out. I'm guessing the info has never been released because of privacy issues.

More info: Harpers Magazine - Jan 1958

Chicago Daily Tribune - July 19, 1959

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jan 19, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Antisocial Activities, Experiments, Psychology, Children, 1950s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |