Experiments

Strange Self-Experiments

I just added a top 10 list of strange self-experiments to the site.This is more material that I wrote a while ago, but which no longer has a home. So I'm relocating it permanently to WU.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Sep 16, 2019 -

Comments (1)

Category: Science, Experiments

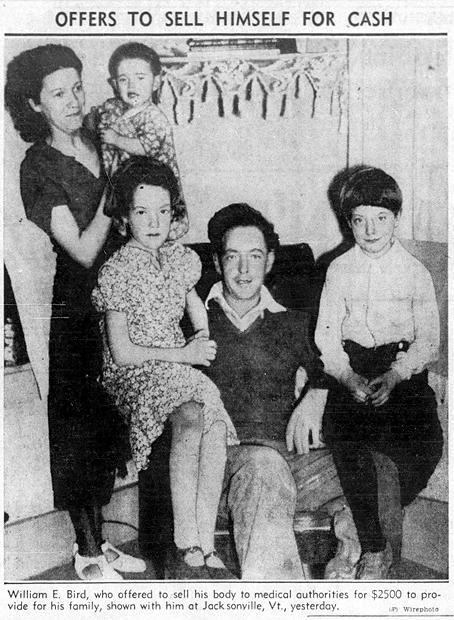

The Man Who Wanted to Sell Himself to Science

Like a lot of people during the great depression, William Bird of Jacksonville, Vermont had fallen on hard times. He was out of work, heavily in debt, and facing eviction. He feared he would soon be unable to feed his wife and three children. So Bird came up with a plan. He would sell himself to science.

Los Angeles Times - Nov 15, 1936

He announced his offer in November 1936 by sending a letter to the local press. It read, in part:

If there is some doctor or group of doctors or scientists who’ll advance me $2500, I’ll agree to pay it back in two years. I have to sort of sell or mortgage myself because that’s the only security I can put up.

Now, if I failed to pay back the money when the time was up, I’d let them do anything they want with me. I’d let them try and kind of experiment on me.

Soon he sweetened the offer by specifying that it would be all right with him if he didn't survive the experimentation process. Naturally, his wife was opposed to the whole idea.

The media spread his unusual offer nationwide. Reporters noted that he was a prime physical specimen — six feet tall, 175 pounds, and a sturdy workman of good habits. In other words, excellent guinea pig material.

An anonymous Texan took sympathy on Bird and sent him $10. However, the scientific community wasn't tempted. No doctors took him up on his offer.

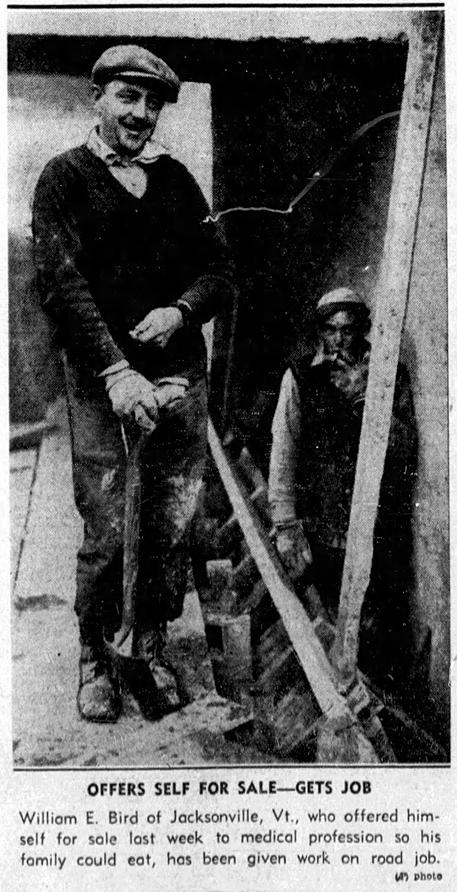

Although Bird didn't manage to sell himself as a human guinea pig, his story nevertheless had a happy ending. Within days of making his appeal, Bird was given a job on a construction project. He said, "I don't know who was responsible for giving me work, but I sure appreciate it." But he also noted that, despite now having a job, his offer still stood. He was still willing to sell himself to science, should some doctor ever want to take him up on it.

Los Angeles Times - Nov 18, 1936

Posted By: Alex - Mon Sep 09, 2019 -

Comments (2)

Category: Science, Experiments, 1930s

The Lice-Infested Underwear Experiment

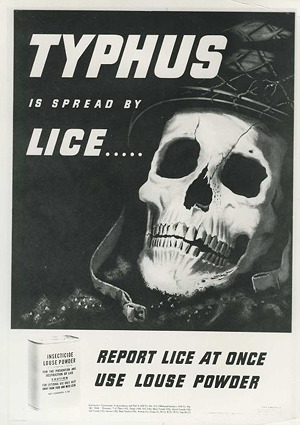

During World War II, millions of men served their country by fighting in the military. Hundreds of thousands of others worked in hospitals or factories. And thirty-two men did their part by wearing lice-infested underwear.

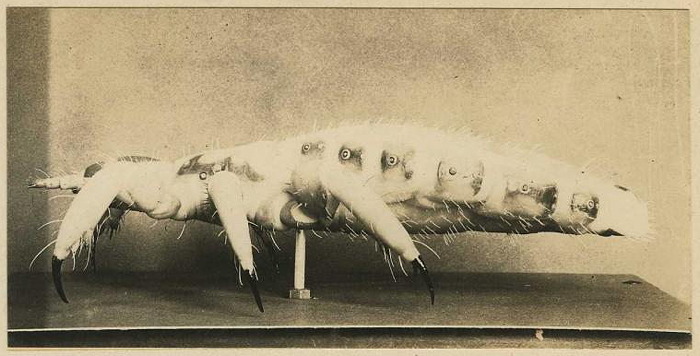

Model of a body louse, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

World War II public health warning

Source: Nat. Museum of Health & Medicine

In an attempt to prevent this, the Rockefeller Foundation, in collaboration with the federal government, funded the creation in 1942 of a Louse Lab whose purpose was to study the biology of the louse and to find an effective means of preventing infestation. The Lab, located in New York City, was headed by Dr. William A. Davis, a public health researcher, and Charles M. Wheeler, an entomologist.

The first task for the Louse Lab was to obtain a supply of lice. They achieved this by collecting lice off a patient in the alcoholic ward of Bellevue Hospital. Then they kept the lice alive by allowing them to feed on the arms of medical students (who had volunteered for the job). In this way, the lab soon had a colony of thousands of lice. They determined that the lice were free of disease since the med students didn't get sick.

Next they had to find human hosts willing to serve as subjects in experiments involving infestation in real-world conditions. For this they initially turned to homeless people living in the surrounding city, whom they paid $7 each in return for agreeing first to be infected by lice and next to test experimental anti-louse powders. Unfortunately, the homeless people proved to be uncooperative subjects who often didn't follow the instructions given to them. Frustrated, Davis and Wheeler began to search for other, more reliable subjects.

The Vancouver Sun - Feb 3, 1943

In theory, the COs were always given a choice about whether or not to serve as guinea pigs. In practice, it wasn't that simple. Controversy lingers about how voluntary their choice really was since their options were rather limited: be a guinea pig for science, or do back-breaking manual labor. But for their part, the COs have reported that they were often eager to volunteer for experiments. Sensitive to accusations that they were cowardly and unpatriotic, serving as a test subject offered the young men a chance to do something that seemed more heroic than manual labor.

Eventually COs participated in a wide variety of experiments, but Davis and Wheeler were the very first researchers to use American COs as experimental subjects. And they planned to infest these volunteers with lice.

More in extended >>

Posted By: Alex - Wed Sep 04, 2019 -

Comments (5)

Category: Health, Insects and Spiders, Experiments, Underwear, 1940s

The Solitude Experiment of Mr. Powyss

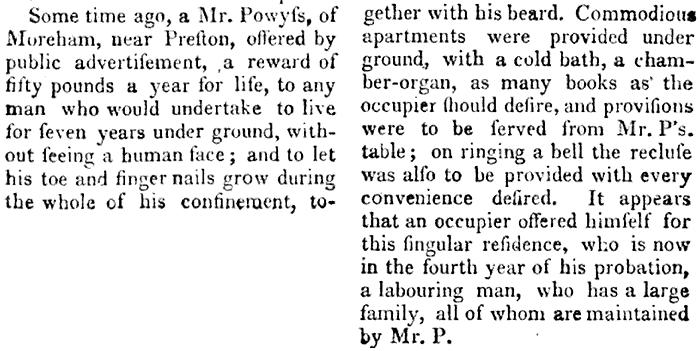

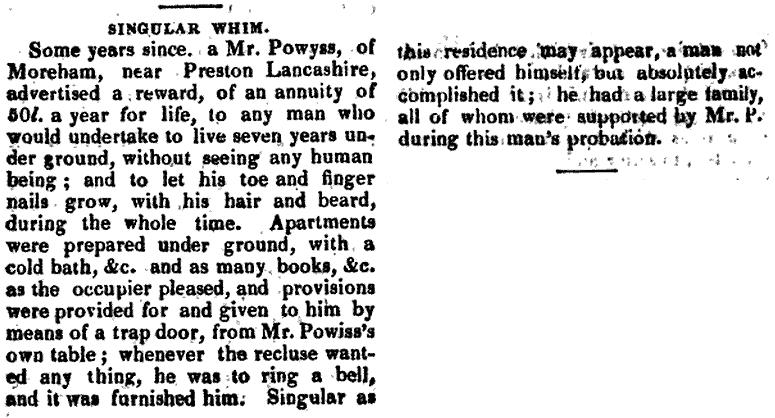

Circa 1793, a Mr. Powyss of Lancashire apparently decided to conduct an unusual psychological experiment by paying a man to live in his basement, in complete solitude, for seven years.Information about this experiment is hard to find. A brief news item appeared about it in 1797:

The Annual Register... for the year 1797

A news story 30 years later reported that the subject of the experiment had emerged after seven years apparently no worse for wear. Or, at least, he had "absolutely accomplished it":

Given the lack of info, I suspect that the entire story might be an urban legend — one of those fake news stories that often made their way into early magazines and newspapers. However, the story has inspired author Alix Nathan to use fiction to fill in the blanks... imagining what might have happened in her recent novel The Warlow Experiment. As reported by the Guardian:

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jul 19, 2019 -

Comments (3)

Category: Experiments, Psychology, Eighteenth Century

Decapitation Experiment

Weird science: How long does a severed head remain conscious? In 1905, Dr Gabriel Beaurieux used the opportunity of the execution of the criminal Henri Languille by guillotine to attempt to find out. From a contemporary newspaper account of the scene:"Languille! Languille!"

Terrible stillness for a moment. And, look! The dead head actually obeys! The eyelids open, and two eyes, abundant with life, glare questioning at Dr. Beaurieux—and then the lids close.

But the doctor has no mercy—he is experimenting. And once more he commands:

"Languille!"

Again the eyelids open, and two soulless eyes attempt to see, to find a point in the space. A conscious struggle really is proceeding, until the lids again close. But for the third time Dr. Beaurieux raises the head up in the air:

"Languille!"

This time in vain. The experiment had lasted thirty seconds, and now the question is:

Has the reflecting movement released other functions of the brain? Did Languille know that they called him, and that he had better awaken and answer? Gruesome it were, if he really had answered, for instance repeated his "Goodbye, you beautiful life!"

The execution of Henri Languille - source: wikipedia

The Racine Journal Times - Aug 23, 1905

Posted By: Alex - Thu May 16, 2019 -

Comments (5)

Category: Death, Science, Experiments, 1900s

Can man fly by flapping his arms?

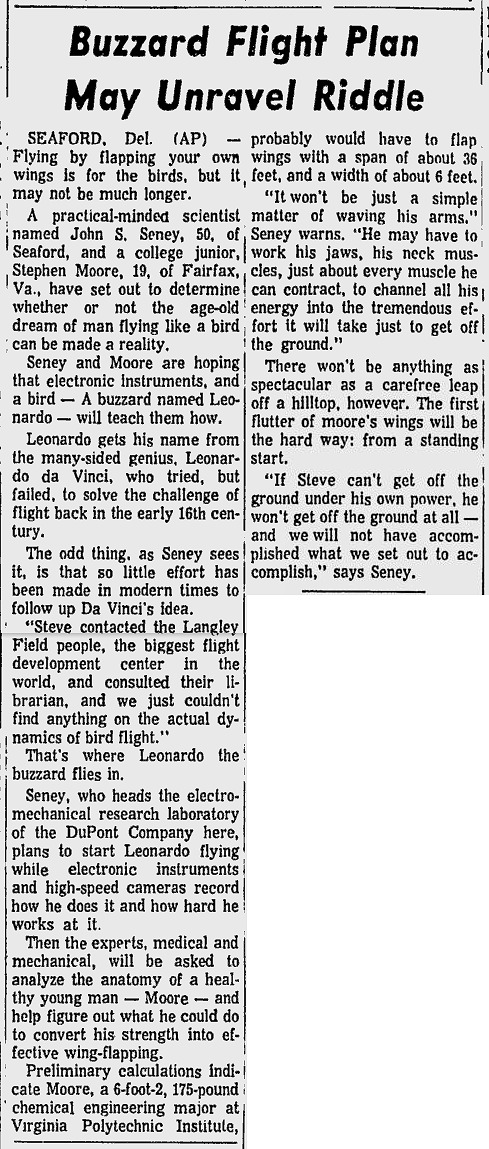

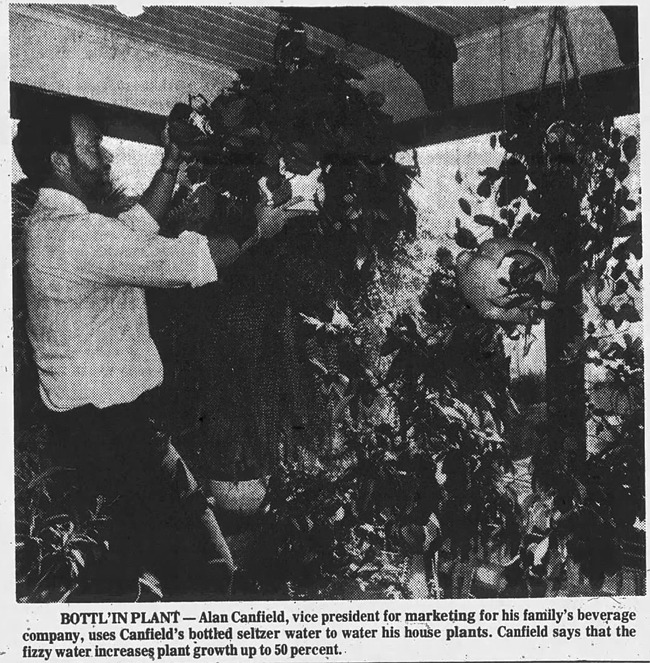

John Seney, an engineer at the Du Pont laboratory in Seaford, Delaware, had an ambitious plan (which he called 'Project Daedalus') to study buzzards and thereby figure out a way to allow a man to fly by flapping his arms — with the help of 36-foot wings strapped to them.Seney's project received quite a bit of media attention for several years in the mid-1960s, but I can't find any report indicating that he ever got to the stage of a test flight.

"Leonardo, the buzzard, is chased in Seaford, Del., basement laboratory of John Seney, 50-year-old scientist who is using the buzzard in his human flight experiments. Pursuing the bird is Stephen Moore who is helping Seney, and if the experiments get off the ground, will see Moore get off the ground with human-propelled wings. That's why they have named the buzzard Leonardo — after Leonardo da Vinci who had dreamed of flying like a bird."

Sarasota Journal - Dec 30, 1964

Baltimore Sun - Feb 21, 1965

Posted By: Alex - Tue Feb 26, 2019 -

Comments (2)

Category: Flight, Experiments, 1960s

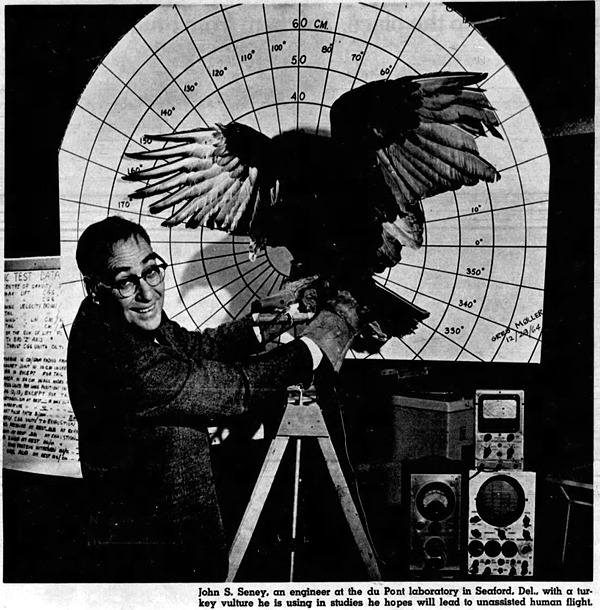

Hangovers Due to Guilty Conscience

In 1973, Professor Robert Gunn advanced this theory.

Twenty years later, he was still pursuing the idea, as you can see in the scientific paper at the link.

To reappraise a prior study of hangover signs and psychosocial factors among a sample of current drinkers, we excluded a subgroup termed Sobers, who report "never" being "tipsy, high or drunk." The non-sober current drinkers then formed the sample for this report (N = 1104). About 23% of this group reported no hangover signs regardless of their intake level or gender, and the rest showed no sex differences for any of 8 hangover signs reported. Using multiple regression, including ethanol, age and weight, it was found that psychosocial variables contributed independently in predicting to hangover for both men and women in this order: (1) guilt about drinking; (2) neuroticism; (3) angry or (4) depressed when high/drunk and (5) negative life events. For men only, ethanol intake was also significant; for women only, being younger and reporting first being high/drunk at a relatively earlier age were also predictors of the Hangover Sign Index (HSI). These multiple predictors accounted for 5-10 times more of the hangover variance than alcohol use alone: for men, R = 0.43, R2 = 19%; and for women, R = 0.46, R2 = 21%. The findings suggest that hangover signs are a function of age, sex, ethanol level and psychosocial factors.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Feb 10, 2019 -

Comments (1)

Category: Science, Experiments, Psychology, 1970s, 1990s, Pain, Self-inflicted and Otherwise, Alcohol

Blue Jay Emetic Unit

As defined by biologist Lincoln Brower, a "blue jay emetic unit" is the amount of cardiac glycosides (a type of poison found in plants such as milkweeds) that will make one blue jay vomit. Brower determined the exact amount by putting cardiac glycosides into gelatin capsules which he force-fed to blue jays.The point of this was that various butterflies ate milkweeds and then became poisonous to the blue jays which, in turn, ate them. Knowing the exact amount of poison needed to make a blue jay vomit allowed Brower to rank each butterfly by its number of blue jay emetic units:

Source: Brower LP (Feb 1969). "Ecological Chemistry." Scientific American 220(2): 22-29.

"barfing blue jay" (picture by Lincoln Brower. Source: ScienceFriday.com)

Posted By: Alex - Wed Oct 03, 2018 -

Comments (3)

Category: Nature, Science, Experiments

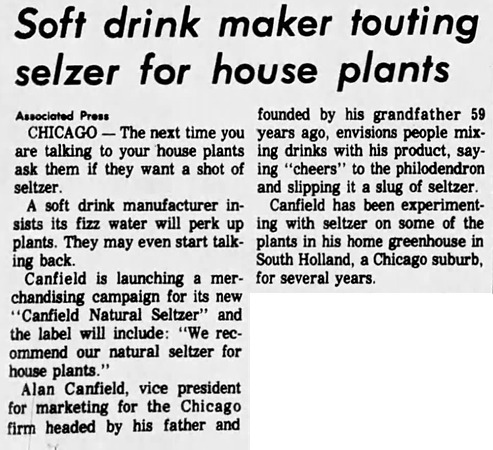

Does seltzer water help plants grow?

In 1980, Canfield's natural seltzer launched a campaign to promote its product as being great for watering house plants. It printed on its labels: "We recommend our natural seltzer for house plants."Could there have been any truth to this claim? Is seltzer water actually good for plants? Well, the only vaguely scientific study I can find addressing this claim (after, admittedly, only a brief search) was a student project conducted at the University of Colorado Boulder in 2002. The student researchers concluded, "Plants given carbonated water not only grew faster but also developed a healthier shade of green in comparison to plants given tap water."

So, maybe Canfield's was onto something. However, if you're thinking of treating your plants to some seltzer water, I imagine you'd want to use water at room temperature, not refrigerated. Cold water might shock their systems.

Marysville Journal-Tribune - June 9, 1980

Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer - May 19, 1980

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jul 19, 2018 -

Comments (12)

Category: Nature, Science, Environmentalism and Ecology, Experiments, 1980s

Dentists smell fear

Recent research reveals that dentists can not only smell fear, but that when they do their job performance significantly declines. From New Scientist:Next, examiners graded the dental students as they carried out treatments on mannequins dressed in the donated T-shirts. The students scored significantly worse when the mannequins were wearing T-shirts from stressful contexts. Mistakes included being more likely to damage teeth next to the ones they were working on.

So, if your fear causes your dentist to start making more mistakes, I assume that will only increase your fear, causing your dentist to make even more mistakes, leading to a downward-spiraling cycle of terror.

The academic study is here.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jun 05, 2018 -

Comments (4)

Category: Experiments, Psychology, Teeth

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |