Experiments

The Bruce Effect

If a pregnant rodent is exposed to the scent of an unfamiliar male, she will often spontaneously abort. This is known as the Bruce Effect, after researcher Hilda Bruce who discovered the phenomenon while working at London's National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) in the 1950s.It's thought that the female rodent does this in order to make herself ready for mating with the new male — because the new male would probably kill the children of the other father once they were born, so why bother carrying them to term. The trick doesn't work with the scent of a castrated male.

The history of the NIMR (pdf - page 208) offers some interesting details about Bruce's research. The Parkes mentioned was Alan Parkes, her boss:

Knowing how skilful perfumers must be in distinguishing between thousands of different odours, they persuaded some Boake representatives to visit NIMR for the purpose of smelling the mice. They invited them to sniff at pieces of cloth that had each been exposed to different cages of various mouse strains. The perfumers had no difficulty in distinguishing the different strains as all had a unique aroma; they even commented that four of the strains were quite similar – all of which had been bred from one original colony at Hampstead. They also noted that the CBA mouse strain, which was fairly new to NIMR, had a wonderful and pleasantly musky smell that could be of commercial interest in perfume manufacture!

Hilda Bruce

Posted By: Alex - Tue Feb 21, 2017 -

Comments (0)

Category: Science, Experiments, Pregnancy, Perfume and Cologne and Other Scents

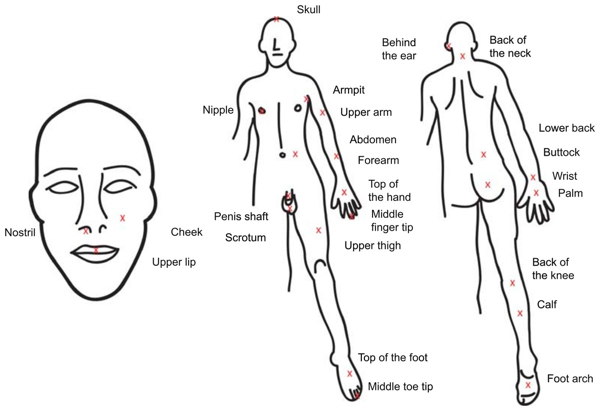

Most painful places to get stung

Before 2014, science had information about which insect species delivered the most painful sting, but it didn't have info about how the painfulness of stings varied by body location. So Cornell University graduate student Michael Smith set about to correct this omission. He used honey bees to sting himself in 25 body locations and then rated the painfulness of the stings on a 1-10 scale. He published his results in the online journal Peer J (Apr 3, 2014, "Honey bee sting pain index by body location").From the article:

And the results:

In 2015, Smith received an Ig Noble Prize for his efforts.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jan 31, 2017 -

Comments (4)

Category: Science, Experiments, Pain, Self-inflicted and Otherwise

When Billboards Become Visible

If you're in the billboard business you'd probably want to know exactly when a billboard becomes visible to drivers. So in 1953 research was conducted at the Iowa State College Experiment Station to get an answer to this question. The study involved having subjects watch miniature billboards slowly approach on a conveyor belt.Source: Duke University Libraries - Archives of the Outdoor Advertising Association of America.

The Duke University blog also notes that in 1958 "The OAAA commissioned Jack Prince, a professor of ophthalmology at Ohio State University, to study the visual dynamics of outdoor advertising, resulting in the first legibility studies of ad copy." I'm not sure how these two studies related to each other. They sound suspiciously similar. And the 1958 studies obviously weren't the first given that the pictures below show research labeled as happening in 1953.

Update: The researcher in the photos is probably Dr. A.R. Lauer of Iowa State's Department of Psychology, and he may have been studying the phenomenon of "Highway Hypnosis."

In the early 1950s there was increasing criticism of the proliferation of billboards along the side of roads. People complained that they were ugly and possibly distracted drivers. So the OAAA sponsored Dr. Lauer to research the safety benefits of billboards, and specifically whether billboards distracted drivers.

Lauer came up with the result that the billboards did distract drivers, but that this was a good thing because it saved them from Highway Hypnosis —entering a trance-like state as they stared at endless, monotonous roads.

The OAAA then took out ads in newspapers promoting Lauer's research and the safety benefits of billboards.

The Des Moines Register - Mar 23, 1958

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jan 20, 2017 -

Comments (9)

Category: Advertising, Experiments, 1950s, Billboards

Survival Experiment

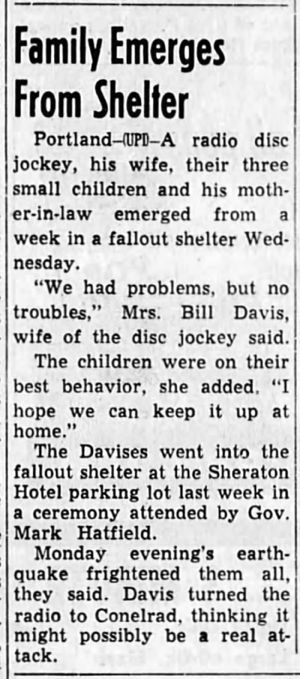

November 1961: As an experiment in survival, Portland radio announcer Bill Davis spent a week confined in a windowless fallout shelter with his family... and his mother-in-law.They survived, although Davis's wife admitted, "There were problems."

One of the problems was that four days into the test an earthquake struck Portland, and the Davis family, cut off from communication, thought it was a nuclear attack.

Medford Mail Tribune - Nov 1, 1961

Medford Mail Tribune - Nov 10, 1961

Medford Mail Tribune - Nov 9, 1961

Posted By: Alex - Sun Nov 27, 2016 -

Comments (0)

Category: Family, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, Experiments, 1960s

The Palatability of Eggs

Dr. Hugh Cott

He assembled a panel of three egg tasters, who were served the eggs scrambled. They then rated them on a 10-point scale. Over a six-year period (1946-1951) they tasted eggs from 212 bird species.

Some of their results: The domestic hen was rated tastiest (8.8 out of 10). The coot, moorhen, and lesser black-backed gull came in second place (8.3 out of 10).

Penguin eggs were "particularly fine and delicate in flavor." Domestic duck eggs were of only "intermediate palatability."

Coming in at the bottom were the eggs of the great tit ("salty, fishy, and bitter"), wren ("sour, oily"), and the oyster-catcher ("strong onion-like flavor"). The eggs of the bar-headed goose made the tasters gag. However, "The freshness of the material available may have been in question."

Cott concluded that brightly colored eggs were, overall, less palatable than camouflaged eggs, but this result has subsequently been challenged. Zoologist Tim Birkhead has also suggested that Cott's experiment would have been more scientifically valuable if the tasters had eaten the eggs raw, because "What predators ever experienced cooked eggs?"

Cott published the full results of his experiment in 1954, in the Journal of Zoology.

The Bend Bulletin - Feb 2, 1948

Posted By: Alex - Wed Nov 02, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Eggs, Experiments, 1940s

LSD for Housewives

Posted By: Paul - Sat Oct 01, 2016 -

Comments (5)

Category: Drugs, Psychedelic, Government, Science, Experiments, 1950s

Must Get Married by August 15th

August 1973: Jean Roth sat in the lobby of a building at Southern Illinois University with signs that read: "I must be married by August 15th for inheritance purposes."

She explained to anyone who asked that she would give $50,000 to any man who agreed to marry her for a year. Many men immediately volunteered to help her. In addition, "Scores of men called the campus newspaper to get the girl's telephone number."

But it turned out, not surprisingly, that the offer was bogus. It was all just a sociology experiment dreamed up by Dr. James M. Henslin, the teacher of a Sociology of Deviant Behavior class that Jean was enrolled in. Explained Dr. Henslin: "In this [class], we deal with deviance from the norm or deviance from what is expected of people. It was an experiment to create a form of deviance and look at the reactions."

So it sounds like it was one of those breaching experiments that became all the rage in sociology classes around that time (late 60s/early 70s).

The class had chosen Jean to be the heir in need of a hubby and had then coached her on how to respond to potential questions. In fact, Jean was already married. Her husband, also a student at the university, reportedly thought the experiment "was stupid."

Ogden Standard-Examiner - Jul 29, 1973

It reminds me of the Dormitory Escape Plan of 1967 that I posted about a couple of months ago, in which a young woman had advertised for a husband as a way to escape from the all-female dormitory that she hated living in.

Also, it seems that Dr. Henslin is the author of several sociology textbooks that are still in use — Essentials of Sociology: A Down-to-Earth Approach and Social Problems: A Down to Earth Approach. He's now retired from Southern Illinois University.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Sep 17, 2016 -

Comments (3)

Category: Experiments, Marriage, 1970s

Killed by own invention

That's one way to cure rheumatism.

The Decatur Herald - July 14, 1958

Charles Werly, 52-year-old Swiss inventor, called in a group of specialists Saturday to demonstrate his new electric-wave apparatus for curing rheumatism.

Werly fitted the machine on himself, switched on the current — and died. The watching doctors said he was killed by a 220-volt charge passing through his body.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Sep 14, 2016 -

Comments (7)

Category: Inventions, Experiments, 1950s

Reaction of lions to a man in a motorized cage

I'm not quite sure what's going on here. This photo (sourced to AP Wirephoto) ran in various papers (such as here) on June 26, 1963. It had the following caption:

And that's it. I've been unable to find out anything else about this strange experiment. But I'd like to know why exactly the zoo was curious about how lions would react to a guy driving around in a motorized cage?

Posted By: Alex - Tue Sep 13, 2016 -

Comments (5)

Category: Animals, Experiments, 1960s

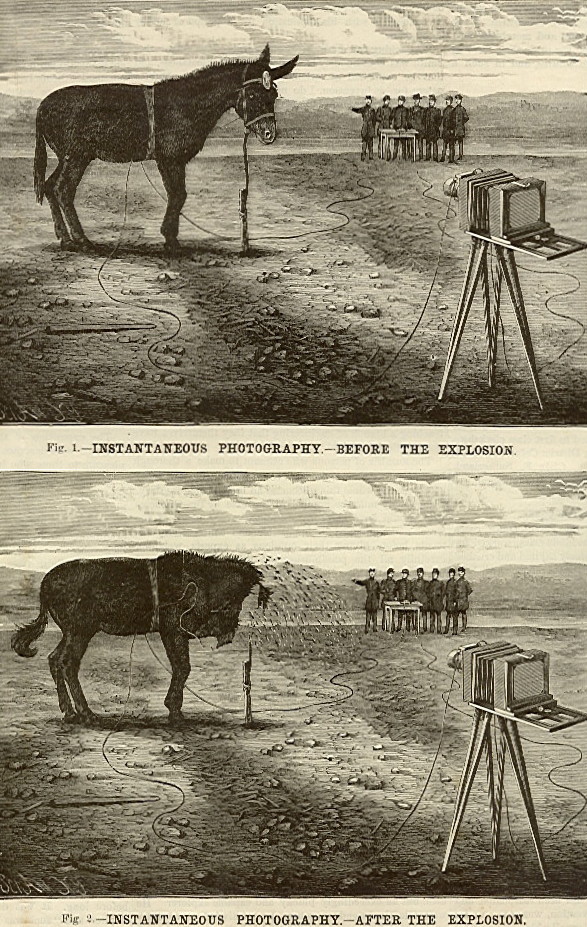

Photographing a mule at the instant its head is blown off by dynamite

Advances in photographic technology that occurred in the 1860s and 70s led to the invention of plates that had exposure times of a fraction of a second. This allowed for "instantaneous photography," as it was called at the time. Moving objects could be frozen in time by the camera.Researchers immediately used this technology to study bodies in motion. Most famously, Eadweard Muybridge in 1878 took a series of images to study the galloping of a horse. Similarly, neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot used instantaneous photography to study the muscular movements of his human patients.

A more unusual application of the technology took place on June 6, 1881, when Mr. Van Sothen, photographer in charge at the United States School of Submarine Engineers in Willett's Point, New York, took an instantaneous photograph of a mule having its head blown off by dynamite. The mule was apparently old and was going to be put down anyway, so it was decided to "sacrifice the animal upon the altar of science."

The resulting photo

Eugene Griffin, First Lieutenant of Engineers, described the details of the experiment in a letter to Lieut. Col. H.L. Abbot:

Several months later Scientific American published an account of the experiment, including several engravings showing before and after scenes:

Scientific American - Sep 24, 1881

Posted By: Alex - Fri Sep 02, 2016 -

Comments (0)

Category: Mad Scientists, Evil Geniuses, Insane Villains, Photography and Photographers, Science, Experiments, Nineteenth Century

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |