Eyes and Vision

The Blonde And Her Companion

Back in the 1950s, the FBI used "a curvaceous blue-eyed blonde, wearing a form-fitting sweater" to help train its agents to improve their powers of observation. The lesson was that if they spent too much time looking at her, they might miss other important details, such as her companion, "public enemy No. 11."Reminds me of the "woman in the red dress" featured in the agent-training-program scene in The Matrix. I wonder if the Wachowskis had heard of the "blonde and her companion" test.

San Bernardino County Sun - Dec 4, 1955

Posted By: Alex - Sat Nov 26, 2022 -

Comments (8)

Category: Police and Other Law Enforcement, 1950s, Eyes and Vision

The Barrett Eye Normalizer

Perfect vision through eyeball massage. At least, that was the claim.

Hearst's International-Cosmopolitan - Oct 1926

Source: American Artifacts

Boston Sunday Globe - Oct 8, 2017

Posted By: Alex - Wed Nov 23, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Frauds, Cons and Scams, Eyes and Vision

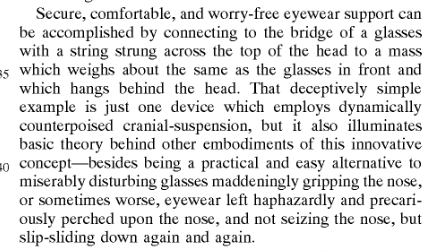

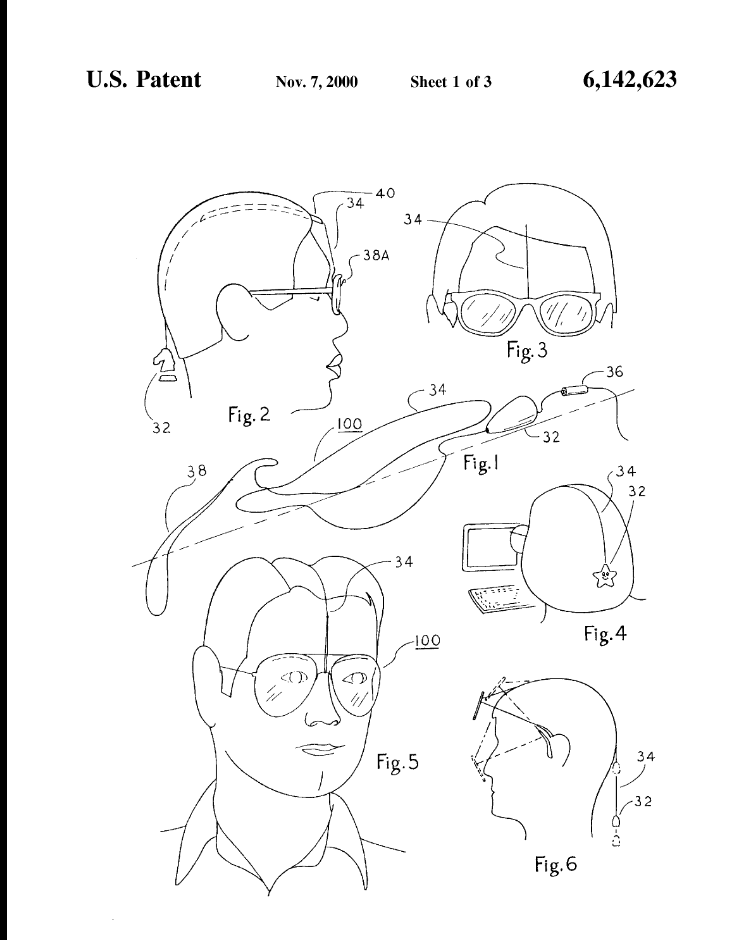

Counterpoised Cranial Support for Eyewear

Full patent here (with other devices included!).

Posted By: Paul - Sun Sep 25, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Ridiculousness, Foolishness, Public Ridicule, Silliness, Goofiness and Dumb-looking, 2000s, Eyes and Vision

The New Eyelashes

Posted By: Alex - Wed Sep 21, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Fashion, 1930s, Eyes and Vision

Jaw Winking

In his 1973 book Thick Description, the anthropologist Clifford Geertz used the example of winking versus twitching to explain what it is that anthropologists should strive to do.An eye twitch and a wink can look identical. But a wink, Geertz explained, is an intentional signal. "To wink is to try to signal to someone in particular, without the cognisance of others, a definite message according to an already understood code." A twitch, on the other hand, is not intentional. It's not meant to convey meaning.

The job of the anthropologist, Geertz argued, was not merely to record facts and events (such as that a person's eye moved) but to be able to interpret the cultural meaning of those events. To be able to differentiate a wink from a twitch.

With that in mind, consider this story reported in the Miami Herald (Apr 30, 1939) about a young man whose eye twitches were constantly misinterpreted:

Such a case was reported some years ago by Dr. Francis C. Grant, an eminent neurologist of Philadelphia, Pa. He had a patient—a young man—whose left eye continually winked every time he sat eating at a table.

Whenever this youth dined in a restaurant, his jaws worked sidewise while chewing food. This caused his right jaw muscles to tug at the muscles controlling his left eye, so that every time he chewed his left eye seemed to wink.

Girls believed the youth was flirting with them. They responded, if flirtatious, or, if not, complained to the manager. In either case, the youth was embarrassed by his muscular malady.

Finally, he was compelled to eat alone at home. He was on the verge of becoming a hermit when he decided to consult Dr. Grant. Examination revealed the "short circuit" cause of his strange "jaw wink" and an operation was performed. The muscles, restored to normal action, ended the distressing condition and the youth could eat normally thereafter.

What I find odd is that I came across these two bits of information (first about Geertz, and second about the jaw-winking young man) while reading completely unrelated texts on back-to-back days. A strange coincidence!

You can read more about Geertz's thoughts on winking and twitching here.

You can read more about 'jaw winking' (aka Marcus Gunn Syndrome) at rarediseases.org.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Sep 08, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Synchronicity and Coincidence, Eyes and Vision

Nose Writing

William Horatio Bates was a New York ophthalmologist who claimed that poor vision could be cured through eye exercises. He was quite well known in the 1920s and 30s.One of his eye exercises was called "nose writing." Here it's described by Margaret Darst Corbett (an "authorized instructor" of his method) in her 1953 book How to Improve Your Sight:

Aldous Huxley was also a fan of the 'Bates Method' and of nose writing, which he described in his 1942 book The Art of Seeing:

I don't think mainstream ophthalmologists have ever put any stock in the benefits of nose writing, but it still has promoters. See the video below.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jun 24, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, Eyes and Vision

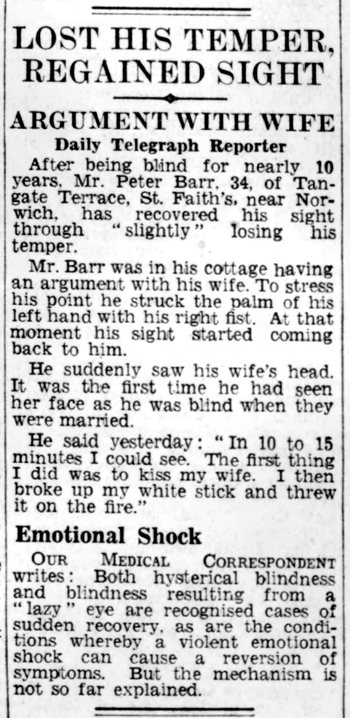

Hit Hand, Regained Sight

June 1955: Peter Barr struck the palm of his left hand with his right fist to stress a point while arguing with his wife. And suddenly he was able to see again. He had been completely blind for three years.

London Daily Telegraph - June 3, 1955

Other cases of accidental cures we've previously posted about:

- the man who regained his sight after a fall

- the woman whose sneeze cured her deafness

- The man whose blindness, deafness, and baldness was cured by lightning

- Blind Man Spontaneously Regains Sight After 30 Years

Posted By: Alex - Sat Apr 16, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Health, 1950s, Eyes and Vision

Blind Soccer

The game, referenced in the news clipping below, was evidently an early example of blind soccer.

The Evening Sun - Dec 17, 1973

The game has now developed into an established Paralympic sport. From wikipedia:

- All players, except for the goalkeeper, are blindfolded.

- The ball has been modified to make a jingling or rattling sound.

- Players are required to say "voy", "go", or something similar when going for the ball; this alerts the other players about their position.

- A guide, positioned outside the field of play, provides instructions to the players.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Apr 07, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Sports, Eyes and Vision

Ancient Greek Warrior Sunglasses

NY Daily News - July 25, 1971

For comparison, the helmet of an ancient Greek warrior:

Posted By: Alex - Sat Apr 02, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Fashion, 1970s, Eyes and Vision

Full-Face Sunglasses

The new trend in sunglasses.I've yet to see someone wearing these out in public, but I'm sure it's only a matter of time before I do.

They're available for $16.99 on Amazon.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Dec 11, 2021 -

Comments (8)

Category: Fashion, Eyes and Vision

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |