Farming

The Great Grand Canyon Deer Drive of 1924

In the early 1920s, the deer population was growing out of control on the Kaibab Plateau north of the Grand Canyon. The area had been designated a National Game Preserve in 1906, and since then the deer population had swelled from around 4000 to as many as 100,000 (by some estimates).Farmer George McCormick came up with a solution. He proposed herding thousands of the deer down into the canyon, over the Colorado river, and then up onto the South Rim where there was plenty of room for them.

Critics pointed out that you can't herd deer, but this didn't deter McCormick. He put together a team of about 50 men on horseback (including the writer Zane Grey) and 100 local Native Americans on foot. Then they set out to herd the deer. Details of how they fared from Arizona Highways magazine (July 2004):

"But as they drew near the deer, instead of retreating, the animals almost invariably dashed through the cordon of men," reported the Sun. "Not only did they refuse to run away forward, but in charging the line, the animals seemed not to care a particle how close they came to the men. In many instances the latter had to give ground.

"One immense buck charged four mounted men, of whom Mr. Grey was one, and the latter reached for his gun, expecting to be run down. The deer just missed the quartet...

The effort continued through that day and the next. But it never approached anything but total chaos, with deer stampeding in every direction.

For more info, there's a detailed article about the deer drive in the Summer 2004 issue of Boatman's Quarterly Review (available as free pdf). Some images from that article:

Posted By: Alex - Thu Oct 24, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Animals, Farming, Really Bad Ideas, 1920s, Arizona

Mrs. Wilmer Steele’s broiler house

In 1974, Mrs. Wilmer Steele's broiler house was added to the National Register of Historic Places. It has the distinction of being the only chicken coop included in the Register.

Mrs. Wilmer Steele's broiler house, located at the University of Delaware Substation near Georgetown, Delaware

The documentation shows that the folks responsible for maintaining the Register were reluctant to add a chicken coop. They initially rejected the application. But finally they were won over, convinced by the argument that it was in Mrs. Wilmer Steele's chicken coop that the modern broiler industry (i.e. breeding chickens for meat rather than for eggs) began.

More info from Wikipedia:

"Ike Long, a broiler caretaker, two of the Steele children and Mrs. Wilmer Steele in front of a series of colony houses during the pioneering days of the commercial broiler industry."

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jun 03, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Farming, Landmarks

Arizona Fumigation

Back in the day you had to be fumigated before they'd let you into Arizona.They've still got agricultural checkpoints on the border, but I've only ever been waved through.

Miami News - May 2, 1924

Thanks to Don Griffith!

Posted By: Alex - Thu May 09, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Government, Officials, Farming, 1920s, Arizona

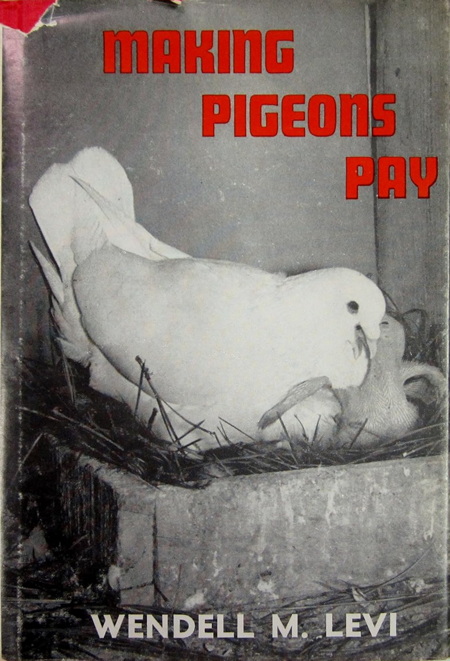

Making Pigeons Pay

Wendell Levi's book is about how to make make money raising pigeons. Not about getting revenge on them. Though the latter would doubtless be a more interesting book.You can read the entire book for free at the Internet Archive.

Browsing through his book, I learned that squab is the term for pigeon meat. (I'm sure most WU readers knew this already, but it was news to me). I've never eaten squab. Nor can I recall ever seeing it for sale in a supermarket, or on a restaurant menu. But it's readily available online, such as at squab.com.

Posted By: Alex - Mon May 06, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Farming, Books

Python meat as the food of the future

Python meat is emerging as a new contender for the food of the future.A report recently published in the journal Nature argues that python meat is potentially the most sustainable source of protein because "In terms of food and protein conversion ratios, pythons outperform all mainstream agricultural species studied to date." In other words, pythons convert most of what they eat directly into meat on their body.

The authors also make the case that farming pythons is more ethical than farming chickens or cows because "Pythons don’t have the same cognitive capacity and choose to remain inactive in small confined spaces when they don’t need to find food."

More info: Nature, New Scientist

People on YouTube who have tried python uniformly report that it's chewy. So grinding it up into a burger might be the way to go.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Mar 23, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Farming

Speed-O-Sex

Chick sexing is the profession of separating newly hatched female from male chicks. Hatcheries employ chick sexors so that they don't waste money feeding the male chicks that aren't going to grow up to lay eggs.Differentiating a male from a female chick is quite challenging, especially doing this quickly. The techniques for doing so were first developed in Japan and then brought to America, where Japanese-Americans dominated the industry for most of the 20th century.

The main industry organization was the National Chick Sexing Association and School. But a smaller school, based in Atlanta Georgia in the late 1940s, called itself Speed-O-Sex.

Gotta wonder if that name ever caused confusion among local residents.

More info: DiscoverNikkei.org

Chicago Japanese-American year book, 1947

Posted By: Alex - Mon Oct 16, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Jobs and Occupations, Odd Names, Farming, 1940s

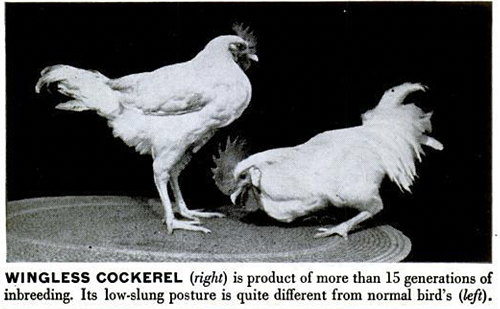

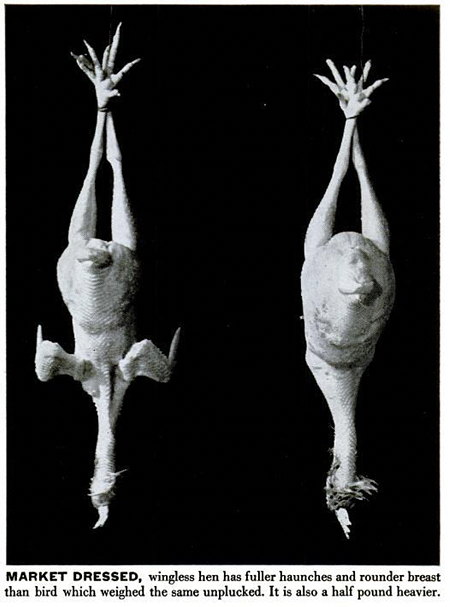

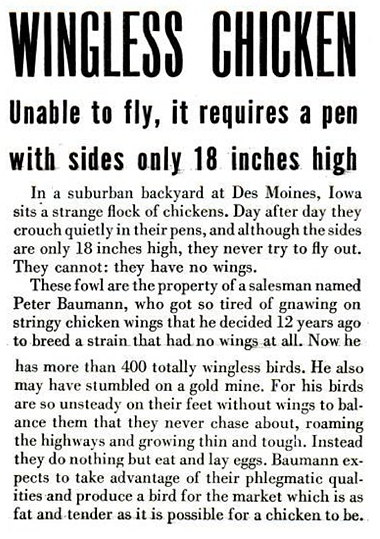

Wingless Chickens

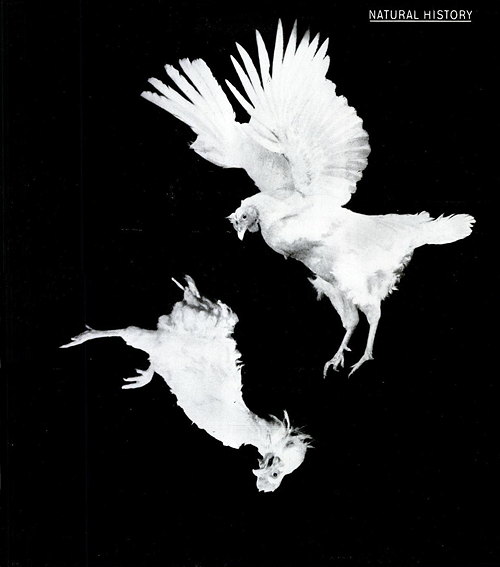

Because he disliked "gnawing on stringy chicken wings," Peter Baumann bred wingless chickens. This was back in the 1940s. Evidently his wingless chickens failed to interest the chicken industry. I haven't been able to find out what became of his flock.To illustrate the helpless quality of these wingless birds, photographer Francis Miller dropped one from six feet to show how it failed to fly, as opposed to a winged chicken that glided downwards.

Images from Life - July 18, 1949:

"Wingless chicken (below) plummets helplessly downward when dropped from 6-foot height, while normal bird settles gently with wings spread"

Posted By: Alex - Sun Nov 13, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Farming, 1940s

Farmer of the Future

Posted By: Alex - Sat Oct 22, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Farming, 1930s, Yesterday’s Tomorrows

The Devil’s Rope Museum

I just returned from a cross-country road trip — visited family on the East Coast then drove back home to Phoenix, which recently became my home. Along the way I stopped at the "Devil's Rope and Route 66 Museum" in McLean, Texas, located on the I-40 east of Amarillo. 'Devil's Rope' is a term for barbed wire.

I hadn't expected the barbed wire section of the museum to be very interesting. I stopped to see the Route 66 memorabilia. But the barbed wire display turned out to be the better part of the museum. Definitely worth checking out if you're ever in the area.

As one might expect, the museum had a lot of info about the use of barbed wire in cattle farming. But it also included a large section about military uses of barbed wire.

Barbed Wire Cutter during World War I

How to build a 'Knife Rest' - War Department, Jan 1944

There were also random oddities, such as a barbed wire hat and boot.

"Hat made by Kevin Compton in 1985. Made from Burnell Four Point Barbed Wire found on the west side of the Rio Grande River near Dixon, New Mexico."

"Barb-Wire Boot"

And in the entrance to the museum, one could view samples of dirt collected from every county in Texas.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jun 05, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Museums, Farming

Lambs in a wind tunnel

After spending more than $40,000 on the experiments the scientists concluded that lambs with short wool got cold faster than lambs with long wool.

Sounds like Nobel Prize material there.

San Francisco Examiner - Dec 9, 1979

I'm not entirely sure, but Deborah Samson's research at the University of Edinburgh seems like it was the original study: "Genetic and physiological aspects of resistance to hypothermia in relation to neonatal lamb survival".

You can download at this link (pdf file) her doctoral thesis describing the research. As usual with things like this, the actual scientific study doesn't seem as wacky as the media report of it.

Update: While browsing through Samson's thesis, I discovered that she had a picture of the lamb "wind tunnel apparatus".

Posted By: Alex - Sun Dec 05, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Experiments, Farming, 1970s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |