Hair and Hairstyling

What Demoralized the Barber Shop

Trollops disconcert some gentlemen. It's amazing the customer in the chair did not have his throat cut.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Dec 28, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Public Indecency, Women, Nineteenth Century, Hair and Hairstyling

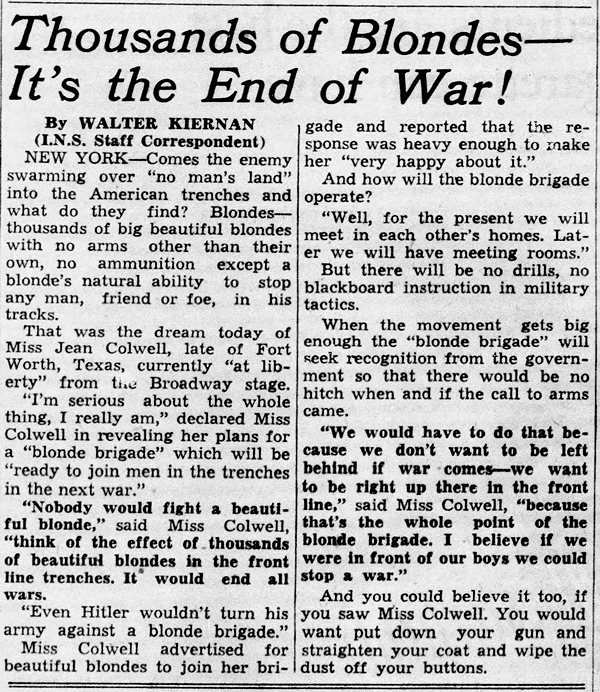

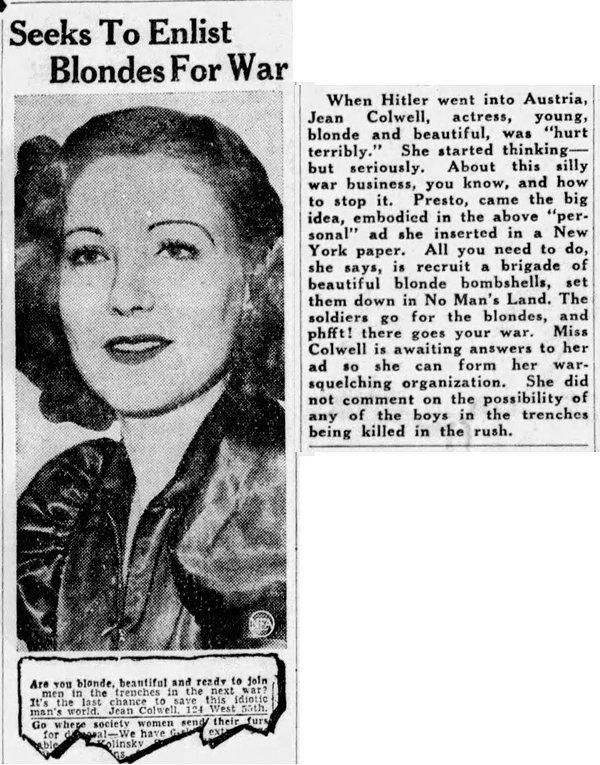

The Blonde Brigade

Apr 1938: Actress Jean Colwell came up with a sure-fire way to end all wars. Her idea was that if a group of beautiful, blonde women stood in between the two opposing armies, in the "no man's land," then the soldiers on each side would refuse to attack because "No soldier will shoot at a good-looking blonde." Peace would be achieved!To make her vision a reality, Colwell placed an ad in a New York newspaper:

The response was enthusiastic, and within a month she had enough volunteers to form a "blonde brigade," all wiling to risk their lives for peace.

Wisconsin State Journal - Mar 29, 1938

Los Angeles Times - Apr 27, 1938

Owensboro Messenger - Apr 2, 1938

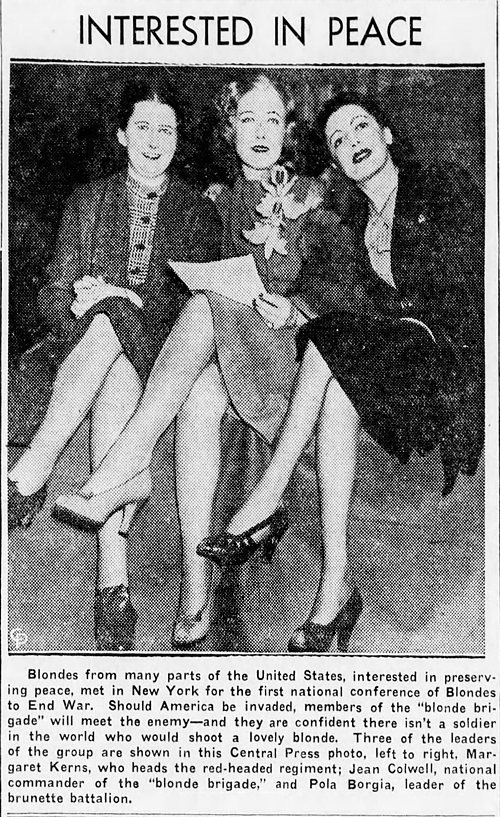

Women of other hair colors didn't want to be left out. So there was soon also a "red-headed regiment" and a "brunette battalion."

San Bernardino County Sun - Apr 30, 1938

Of course, none of these women were ever shipped to the front line to serve as a human shield. Colwell herself spent the war in Forth Worth, Texas performing in plays. After the war she moved to Japan as a civil service worker. When she died in 1986, she was back in Fort Worth. I haven't found any info on what she did between 1946 and 1986.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Nov 14, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: War, 1930s, Women, Hair and Hairstyling

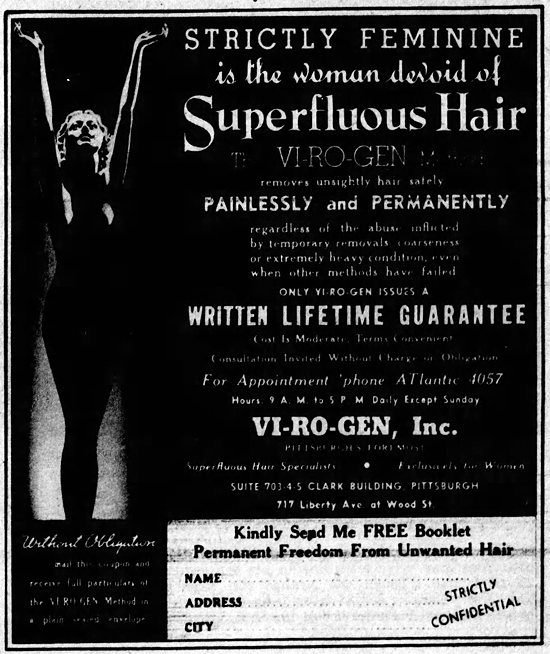

Strictly feminine is the woman devoid of superfluous hair

The more often I say that sentence, the stranger it sounds.

Pittsburgh Press - July 30, 1939

Posted By: Alex - Fri Nov 05, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Advertising, 1930s, Hair and Hairstyling

Aluminum Al

In 1952, scientists at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady created the aluminum version of a Chia Pet. They called him "Aluminum Al".Source: Google Arts and Culture

Posted By: Alex - Mon Sep 13, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Science, 1950s, Hair and Hairstyling

Baldness at the FBI

William Sullivan was a high-ranking official at the FBI from 1961 to 1971, when Hoover was director. In his tell-all book about his time there (The Bureau My Thirty Years in Hoover's FBI) Sullivan claimed that one of Hoover's many eccentricities was that he didn't like bald-headed men... to the extent that Hoover wouldn't allow bald men to be hired as agents, because he believed their baldness made a bad impression:Flacking for the FBI was part of every agent's job from his first day. In fact, "making a good first impression" was a necessary prerequisite for being hired as a special agent in the first place. Bald-headed men, for example, were never hired as agents because Hoover thought a bald head made a bad impression. No matter if the man involved was a member of Phi Beta Kappa or a much-decorated marine, or both. Appearances were terribly important to Hoover, and special agents had to have the right look and wear the right clothes...

Though a bald-headed man wouldn't be hired as an agent, an employee who later lost his hair wasn't fired but was kept out of the public eye.

I guess that means that, under Hoover, Walter Skinner would never have made the cut.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jun 30, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Government, Officials, Hair and Hairstyling

Corporate Pubic Hair Shaving

Posted By: Paul - Fri Jun 11, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Hygiene, Advertising, Public Indecency, Genitals, Hair and Hairstyling

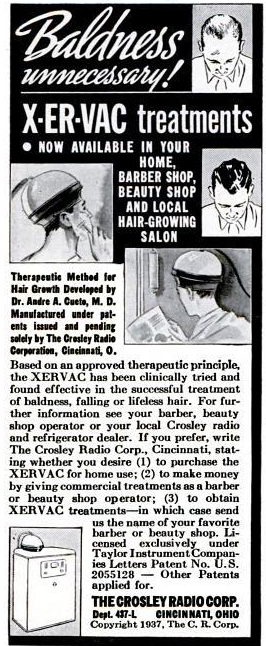

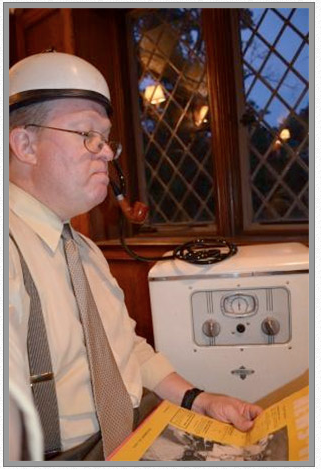

The Xervac Anti-Baldness Device

Read all about it here.

And here, source of the photo below.

Posted By: Paul - Tue May 11, 2021 -

Comments (8)

Category: Technology, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1930s, Hair and Hairstyling

Combined hat and comb

In 1920, Alva Dawson of Florida was granted a patent for a "combined head covering and hair comb". In his patent he explained:I'm pretty sure it wasn't possible to use this hat-comb without rendering yourself very conspicuous.

Popular Science - Oct 1920

Posted By: Alex - Sun May 02, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Patents, Headgear, 1920s, Hair and Hairstyling

Hair Popping

Hair popping was developed as a claimed cure for baldness around the 1950s. It involved pulling on the scalp until it made a popping sound. And yes, it was apparently quite painful.Some details from Baldness: A Social History by Kerry Segrave.

Hair popping, as a cure for baldness, fell out of fashion. But recently it's re-emerged as a fad on TikTok. Though it's now being called 'scalp popping'.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Apr 21, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, Hair and Hairstyling

Cow-Tongue Baldness Cure

Several sources have independently reported that the way to cure baldness is to have a cow lick your head.

Regina Leader-Post - Mar 8, 1984

November 29, 2000

PEREIRA, Colombia -- Want to lick hair loss? A Colombian hairdresser says he has found a way to lick baldness -- literally. His offbeat scalp treatment involves a special tonic and massage -- with a cow's tongue. "I feel more manly, more attractive to women," says customer Henry Gomez. "My friends even say 'What are you doing? You have more hair. You look younger.'"

Posted By: Alex - Sat Apr 10, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, Cows, Hair and Hairstyling

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |