Health

Regained sight after fall

Another case of an improbable cure.Eugene W. Phillips, 60, had been blind for 16 years. Then, in August 1972, he fell off his back porch, puncturing his back with a stick and hitting his head on the ground. But he also partially regained sight in one eye. His doctor concluded that the fall had jarred loose a membrane that had been covering the optic nerve.

Bonham Daily Favorite - Aug 8, 1972

Provo Daily Herald - Aug 9, 1972

Related:

Posted By: Alex - Mon Mar 30, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Health, 1970s, Eyes and Vision

Intestinal Chimney Sweeps

Back in the early twentieth century, the French laxative Jubol ran an ad campaign that featured tiny chimney sweeps climbing up into intestines and scrubbing them out.It reminds me of that old urban legend about Richard Gere and the gerbils.

Image source: vintage-ads — historical source: Rire - Dec 14, 1918

"Voila le petit ramoneur de l'intestin..." (Here's the little chimney sweep of the intestines)

L'Illustration - June 10, 1916

Posted By: Alex - Sat Mar 28, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Health, Advertising, 1910s

The man whose blindness, deafness, and baldness was cured by lightning

We've reported a few cases on WU of people who have experienced accidental (and improbable) cures, such as the woman whose deafness was cured by a sneeze. One of the most famous examples of this phenomenon is the case of Edwin Robinson, who claimed that being struck by lightning cured him of his blindness and near-total deafness.The lightning strike occurred on June 4, 1980 when he ventured outside of his home in Falmouth, Maine to rescue his pet chicken from the rain. After lying unconscious for 20 minutes, the 62-year-old Robinson awoke to find himself cured of the ailments that had plagued him since a road accident nine years earlier. An ophthalmologist who examined him, Dr. Albert Moulton of Portland, said: "There is no question but that his vision is back. He can't move his eyes, but his central vision is back... I can't explain it. I don't know who can. I know some of my peers in Washington, maybe, will say it's hysterical blindness. I can't see it. It couldn't have lasted this long. From the physical findings originally, he was definitely blind."

Edwin Robinson reads about his miraculous recovery

Later, Robinson even claimed that new hair had begun to grow on his bald head. He remarked to the NY Times, "I'm all recharged now, literally... It's coming in thick. My wife is all excited about it. I was bald for 35 years. They told me it was hereditary."

Los Angeles Times - July 5, 1980

Later, Timex took advantage of Robinson's fame to feature him in a 1990 ad. Although the messaging seems a bit confused. Once broken, but now miraculously fixed?

Also, it's hard to tell, but he doesn't seem to have a full head of hair. He must have lost it again.

Source: AdsPast.com

St. Louis Post Dispatch - June 7, 1980

Posted By: Alex - Tue Mar 24, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Health, 1980s, Eyes and Vision

The Wonder Glove

It was a mitten lined with “uranium ore,” sold in the early twentieth century as a cure for arthritis. It was part of the fad for radioactive cure-alls.Source: Your Money and Your Life: An FDA Catalog of Fakes and Swindles in the Health Field — an FDA pamphlet published in 1963 that includes a variety of other quack medical devices.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Mar 20, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Health, 1960s

Helmet Heat

-Wausau Daily Herald (Apr 20, 1957)

The heat might actually have helped to alleviate symptoms. So, in that sense, it wasn't a bad idea. But I doubt many people were willing to wear this for an extended period of time.

Dayton Daily News - June 16, 1957

Wausau Daily Herald - Apr 20, 1957

Posted By: Alex - Thu Feb 06, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Health, Cures for the common cold, 1950s

Monitor grandma’s health via her butt

A new gadget, the VISSEIRO Smart Chair Pad, promises to allow people to remotely monitor the health of loved ones via a seat cushion. When someone (a grandmother, for example) sits on the cushion, it's able to record various vital signs through her buttocks. It can then send this info to an app on the phone of the granddaughter, offering reassurance that grandma is still alive and doing well.My question is: if the vital signs flatline, how do you know if grandma is dead, or has simply stood up?

More info: visseiro.com

Posted By: Alex - Fri Sep 20, 2019 -

Comments (7)

Category: Health, Inventions

Healthiest US Pair

This is quite a distinction conferred by the 4-H congress of Chicago. I assume they examined every person in the USA before deciding.

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Sep 07, 2019 -

Comments (0)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Health, 1930s

The Lice-Infested Underwear Experiment

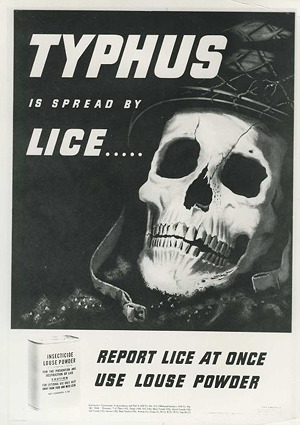

During World War II, millions of men served their country by fighting in the military. Hundreds of thousands of others worked in hospitals or factories. And thirty-two men did their part by wearing lice-infested underwear.

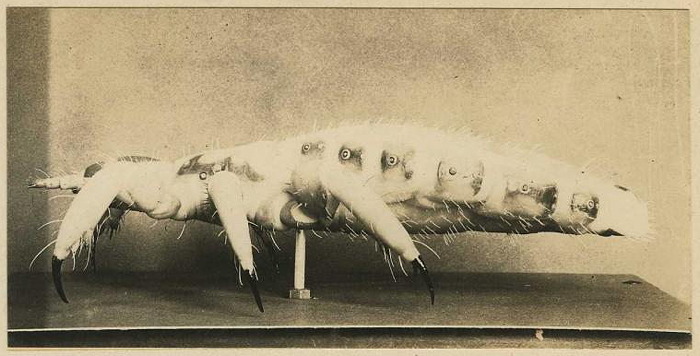

Model of a body louse, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

World War II public health warning

Source: Nat. Museum of Health & Medicine

In an attempt to prevent this, the Rockefeller Foundation, in collaboration with the federal government, funded the creation in 1942 of a Louse Lab whose purpose was to study the biology of the louse and to find an effective means of preventing infestation. The Lab, located in New York City, was headed by Dr. William A. Davis, a public health researcher, and Charles M. Wheeler, an entomologist.

The first task for the Louse Lab was to obtain a supply of lice. They achieved this by collecting lice off a patient in the alcoholic ward of Bellevue Hospital. Then they kept the lice alive by allowing them to feed on the arms of medical students (who had volunteered for the job). In this way, the lab soon had a colony of thousands of lice. They determined that the lice were free of disease since the med students didn't get sick.

Next they had to find human hosts willing to serve as subjects in experiments involving infestation in real-world conditions. For this they initially turned to homeless people living in the surrounding city, whom they paid $7 each in return for agreeing first to be infected by lice and next to test experimental anti-louse powders. Unfortunately, the homeless people proved to be uncooperative subjects who often didn't follow the instructions given to them. Frustrated, Davis and Wheeler began to search for other, more reliable subjects.

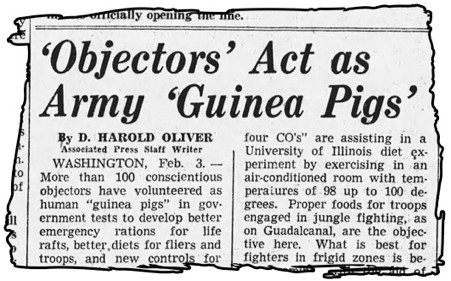

The Vancouver Sun - Feb 3, 1943

In theory, the COs were always given a choice about whether or not to serve as guinea pigs. In practice, it wasn't that simple. Controversy lingers about how voluntary their choice really was since their options were rather limited: be a guinea pig for science, or do back-breaking manual labor. But for their part, the COs have reported that they were often eager to volunteer for experiments. Sensitive to accusations that they were cowardly and unpatriotic, serving as a test subject offered the young men a chance to do something that seemed more heroic than manual labor.

Eventually COs participated in a wide variety of experiments, but Davis and Wheeler were the very first researchers to use American COs as experimental subjects. And they planned to infest these volunteers with lice.

More in extended >>

Posted By: Alex - Wed Sep 04, 2019 -

Comments (5)

Category: Health, Insects and Spiders, Experiments, Underwear, 1940s

The Concrete Enema

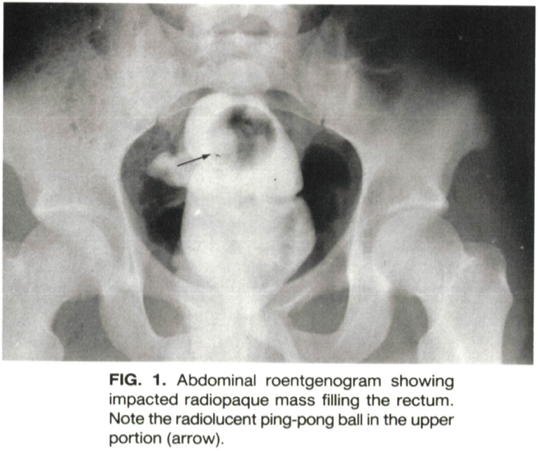

It provided the title for Chuck’s classic 1996 collection of weird news (and if you don't have Chuck's book you really should do yourself a favor and get it. It deserves to be in every home library). However, we’ve never posted about the incident itself here on WU. So I thought I'd remedy that oversight.In 1987, two doctors reported an unusual case in The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. It involved a 20-year-old man who had shown up at an emergency room complaining of rectal pain. Examination of his rectum revealed a “hard stony mass,” and eventually the patient disclosed how the mass had gotten there:

Remarkably, the doctors were able to remove the concrete mass without any damage to the patient's rectum. It had formed a perfect cast of the interior of the rectum, even showing “grooves produced by mucosal folds.”

Removal revealed another unusual detail: a ping-pong ball mixed in with the concrete. Apparently the patient didn’t explain what the ball was doing there. The doctors hypothesized that it had been "inserted after the enema as a plug to promote retention… Instead, peristaltic contractions forced the air-filled plastic ball deeper into the hardening concrete, accounting for its location in the upper end of the mass."

After resting overnight, the patient was able to leave the hospital the following morning, no worse for wear. One can only hope that he had learned a valuable life lesson: that it's really not a good idea to use concrete as an enema.

I wonder what became of the concrete enema. Was it thrown away in the trash? This seems most likely. Or perhaps it's sitting in a box in a medical archive. Or, and this is my favorite idea, perhaps one of the doctors saved it to use as a paperweight. Whatever the case may be, if it still survives it definitely would be a great exhibit to include in a museum of the weird.

More info: Peter J. Stephens and Mark L. Taff. (1987). “Rectal Impaction Following Enema with Concrete Mix.” The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, 8(2): 179-182.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 28, 2019 -

Comments (0)

Category: Health, Sex Toys, 1980s

Youngster got high on hamburgers

A strange affliction to suffer from.

The Alexandria Town Talk - Jan 14, 1976

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 12, 2019 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Health, 1970s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |