Health

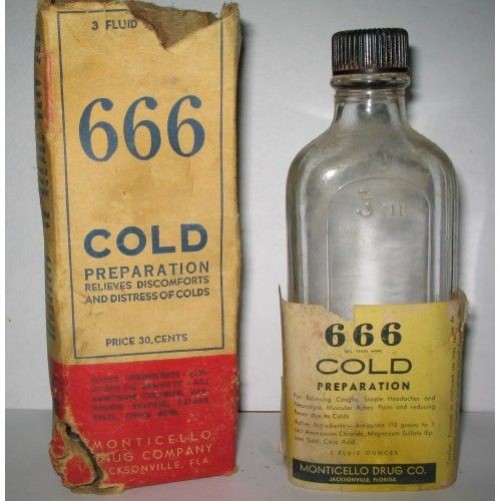

Cold Medicine of the Beast

Still being made and sold today.

Home page here.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Apr 17, 2016 -

Comments (9)

Category: Health, Religion, Superstition, Nineteenth Century

Miss Medic Alert Followup

I do not necessarily wish to claim a Google-fu superior to Alex's, but I did find an image of the 1965 Miss Medic Alert.

Original article here.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Apr 06, 2016 -

Comments (3)

Category: Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Contests, Races and Other Competitions, Health, 1960s

Coffee vs Alcohol

Coffee consumption protects the liver from alcoholic cirrhosis. The more coffee the better the effect according to a 22 year study involving 125,000 subjects. Tea does not have the same effect, ruling out caffeine as the cause. So, hit the coffee if you drink much but not for any other form of the disease as alcoholic cirrhosis is the only form it benefits.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Feb 20, 2016 -

Comments (4)

Category: Health, Coffee and other Legal Stimulants, Diseases, Alcohol

Kenny The Tiger

Of course Kenny the tiger did not have Downs syndrome, his deformities were due to inbreeding. He was an interesting looking cat though. Unfortunately, Kenny's lifespan was significantly shortened as well, he only lived for 10 years. So to the breeders, in the words of Kyle and Stan on South Park, "They killed Kenny!" "You bastards!"

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jan 16, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Animals, Freaks, Oddities, Quirks of Nature, Health, Nature

The Case of the Allergic Bride

Joyce and Nolan Holdridge married in San Francisco on March 3, 1947. He was a watchmaker, recently out of the Navy. She was a telephone operator.At first their marriage was a happy one, but a few months after their wedding Joyce began to grow sick. Her eyes reddened and swelled shut. She broke out in an irritating skin rash that covered her from head to toe.

Joyce sought help from doctors, psychiatrists, and skin specialists, but in vain. Eventually her condition grew so bad that she was hospitalized at the Veterans Administration Hospital in San Francisco. And it was here, while she was under constant observation, that the doctors noticed an unusual pattern to Joyce's outbreaks.

While she was at the hospital, her symptoms gradually subsided, but when she visited her husband each weekend they promptly flared up again. Soon the doctors arrived at a startling conclusion. Joyce appeared to be allergic to her husband.

Separation The Only Option

Further observation made it clear that Joyce wasn't reacting to a cologne her husband was wearing, or some other chemical irritant that could easily be removed. She appeared to be allergic to the man himself. His mere presence. In fact, even mentioning her husband's name caused Joyce to break out in hives.

The doctors diagnosed Joyce's allergy as neurodermatitis, and counseled her that all attempts at a cure would be futile as long as she was living with her husband.

So in March 1948, a year after getting married, Joyce and Nolan began living apart. He stayed in San Francisco and she moved to Los Angeles. This cured Joyce's rash, but eventually the couple decided that living separate lives, while still married, didn't make sense. So in July 1949, Joyce filed for divorce from Nolan.

Divorce Trial

The divorce trial was held in the Los Angeles Superior Court of Judge Ray Brockmann on July 25, 1949. Nolan didn't attend, as he wasn't disputing the facts.

Joyce told the judge that she had no complaint about her husband's behavior. In fact, he was "the finest husband a woman could ask for" and she loved him deeply, but every time they were together she broke out in a rash from head to toe. So at the advice of physicians and psychiatrists, she had to leave him.

To back up this claim she produced a medical report from Dr. Gordon Dayton of the San Francisco Veterans Hospital who wrote, "[Joyce] had been suffering from a severe generalized dermatitis manifested by reddened, swollen, itching and scaling areas most marked over the hands, forearms, chest, neck, face and thighs. It soon became evident that there was something physical in the home or about the person of her husband to which she was sensitive."

\Determining Fault

Judge Brockmann listened with sympathy to Joyce's presentation of her case. However, there was a problem. In order to grant a divorce, it had to be shown that one of the spouses was at fault, and it wasn't clear that anyone's behavior was to blame in this case.

It used to be a standard requirement in American law that a couple could only get divorced if one of the spouses was at "fault" for causing the breakdown of the marriage. Actions that constituted fault included adultery, abandonment, or cruelty.

Divorce-seekers would regularly stretch facts in order to argue that their spouse was somehow to blame for ruining the marriage. For instance, one man complained that the snores of his wife's dog had made it impossible to sleep in the same room with her. In another case, a wife charged that her husband would cruelly shut off his hearing aid so that he couldn't hear her side of arguments. Similar strange marital complaints were a regular feature in weird news columns of the time.

It was only in 1970 that California made "no-fault" divorces legal, allowing couples to separate simply because they wanted to. All other states eventually followed suit.

But in 1949, demonstrating fault was still the legal requirement to obtain a divorce, and Judge Brockmann didn't think that an allergic reaction was anyone's fault. So he pressed Joyce for details, trying to determine if Nolan was ever cruel to her.

Joyce suggested the allergy was cruelty, but the judge disagreed, and with that he denied her request, ruling that being allergic to your spouse was not grounds for divorce.

Controversy

Joyce's case caused a popular sensation. Headlines trumpeted the case of the "allergic bride." One widely reprinted photo showed Joyce holding her pet dog "Taffy." The caption noted that although she was allergic to her husband, the dog didn't seem to bother her in the least.

Newspapers generally treated the case as yet another example of the "silly" reasons that people got divorced. However, Joyce's effort to obtain a divorce received a flood of popular support, particularly from women. Judge Brockmann reported receiving hundreds of letters, mostly from wives, urging him to reconsider his ruling. A number of these letter writers claimed that, like Joyce, they were allergic to their husbands. Wrote one woman, "This is a real cause for divorce. It is a cause made by nature — not by man."

Resolution

Thankfully Joyce and Nolan were not doomed to remain married forever. Judge Brockmann suggested that there was another legal option available to end their marriage — annulment. Unlike a divorce, an annulment could be granted on the basis of "physical incompatability." There was no need to determine fault.

So in September Nolan filed suit, asking that his marriage be dissolved since Joyce could not perform her "wifely duties." Judge Brockmann again heard the case, but this time he promptly granted an annulment, allowing Joyce and Nolan to go their separate ways. Some years later Nolan remarried, and there was no report that his new wife developed any allergic reaction to him. What became of Joyce is not known.

Postscript

Joyce and Nolan's case was seen as being a first of its kind, setting a legal precedent. But Judge Brockmann warned others not to try to get out of marriage on "allergy grounds" unless they could produce valid medical evidence that would withstand a "scrutinizing judicial eye."

Inevitably his advice was ignored, and throughout the 1950s a number of wives (Rose Savenick of Los Angeles, Zelam Ansley of Seattle, Virginia Miller of Beverly Hills, etc.) filed for divorce on the grounds that they were allergic to their husbands. All won their cases, perhaps because of the precedent set by Joyce and Nolan. Eventually the adoption of "no-fault" divorce laws made it unnecessary for women to plead allergies to get out of a marriage.

But what about the men? Was spousal allergy a problem that only affected wives? In fact, the media did report about a few husbands who were allergic to their wives, but for whatever reason these husbands didn't seek divorces. For instance, in 1962 Dr. Michael O'Donnell wrote in the British medical magazine Family Doctor about a man who had developed asthma because he was allergic to his wife. However, "It was not until the death of the wife—a formidable and overpowering lady—that the doctors made their discovery," wrote the physician. Because on the day of her death, the man's asthma attacks stopped. "He has never had an attack since," observed O'Donnell.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Sep 09, 2015 -

Comments (15)

Category: Health, Wives, Divorce

Margarita Photodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis involving fruits and vegetables has been described most often as an occupational hazard among citrus workers and celery harvesters, because these foods contain high concentrations of furocoumarins. Isolated cases have also been described after nonoccupational exposure. One of the largest outbreaks was reported among 12 children in a day camp who were making pomanders from limes.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jun 09, 2015 -

Comments (5)

Category: Health

Unfortunate Allergy

Some women, aproximately 12%, are allergic to their partner's semen. Even worse, some men are allergic to their own semen. The allergy causes some nasty reactions in both cases unfortunately.

Posted By: Alex - Mon May 25, 2015 -

Comments (1)

Category: Freaks, Oddities, Quirks of Nature, Health, Can’t Possibly Be True, Sex Lives Worse Than Yours, Genitals

ABOUT D@%N TIME

France has enacted a law limiting excessively thin models from working until their BMI reaches a minimum level set forth in the law. Fines and even jail time can be leveled against fashion houses and modeling agents trying to use models that are thinner than the law allows. Its about time we quit letting vanity destroy our little girls.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Apr 05, 2015 -

Comments (13)

Category: Addictions, Eating, Design and Designers, Fashion, Food, Nutrition, Health, Disease, Mental Health and Insanity

Spring Ahead 2015

Heart attacks increase 25% the Monday after spring ahead and decrease by 21% the Monday after fall behind.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Mar 03, 2015 -

Comments (6)

Category: Health, Disease, More Things To Worry About

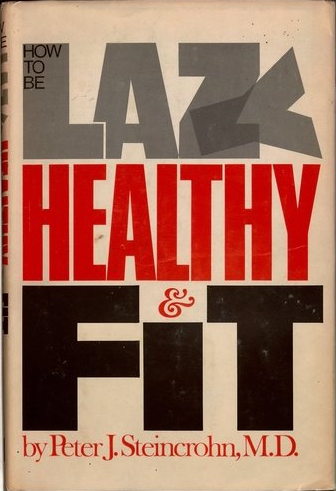

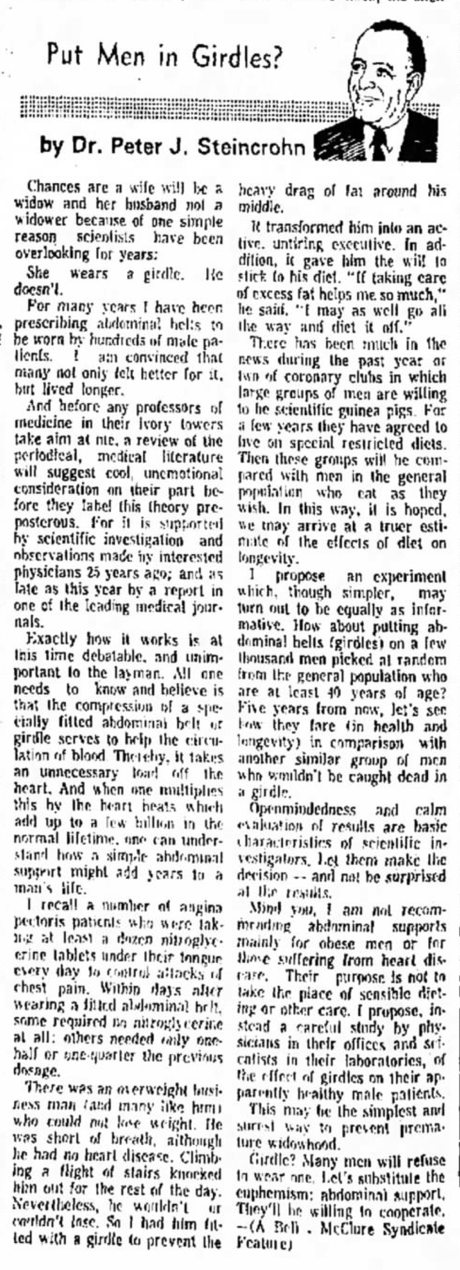

Put Men in Girdles

Dr. Peter Steincrohn's 1969 book (available used on AmazonHe felt that all men over 40, in particular, should be wearing girdles just like their wives (this was the 1960s), because he believed that girdles promoted good circulation and thus meant the heart didn't have to work as hard pumping blood. Wearing a girdle, he promised, would "add years to a man's life."

The Abilene Reporter-News - Nov 23, 1964

Posted By: Alex - Fri Feb 27, 2015 -

Comments (1)

Category: Health, Books, 1960s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |