Inheritance and Wills

Clarinet made from bones

When Signor Ubaldo Ubaldi, an Italian criminal, died in 1950, he left £12 in his will so that his bones could be polished and made into clarinet mouthpieces.At least, that was widely reported at the time. I have doubts about the veracity of the story, though I can't disprove it either. I can't find any report that Ubaldi's last wishes were carried out.

Sydney Sun - Oct 19, 1950

Adelaide News - Nov 1, 1950

click to enlarge

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jan 06, 2025 -

Comments (4)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Music, 1950s

Sir John Waller looks for a wife

The good news for Sir John Waller (1917-1995) was that he inherited a fortune. The bad news was that in order to inherit the full amount (rather than just the annual interest payments) he had to marry and have a son.This presented a problem since he was homosexual and had no interest in marrying a woman. Nevertheless, he undertook to satisfy the requirements to obtain his inheritance.

In 1964 he proposed to singer Brigitte Bond soon after meeting her. But he subsequently discovered that she was transsexual and couldn't bear him a child. The engagement was called off two months later.

In 1974 he married Anne Eileen Mileham, and she soon got pregnant — but gave birth to a daughter. That didn't satisfy the inheritance requirements, so again, he promptly divorced her. The scuttlebutt is that he wasn't actually the father of the child anyway.

He died without ever having inherited the money.

More info: wikipedia

London Daily Express - Feb 23, 1995

In the video biography of Brigitte Bond below, there's some discussion (beginning at 11 minutes) of her brief engagement to Waller. Besides her association with Waller, Bond is famous for being the inspiration for the Beat Girl logo used by the ska band the Beat.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 25, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Inheritance and Wills, Divorce, Marriage

The Strange (spurious) Will of Francesca Nortyuege

In various books of odd facts one can find, briefly related, the story of the strange last will of Francesca Nortyuege. The story goes that when Nortyuege, a famous reformer from Dieze, died in 1903 she left her fortune to her niece on the condition that the family goldfish always be kept dressed in tights.I pasted an illustrated version of the story below, from Mindblowers (1982) by Chet Stover. But it also appears in Karl Shaw's Oddballs and Eccentrics (2004), as well as in many newspaper columns.

Los Angeles Times - July 13, 1954

I suspected the story wasn't true, but it took me a while to locate its source — due to the many variant spellings of Nortyuege (Nortuega, Nortyuega, etc.). Finally I tracked it down to R.L. Ripley's 1929 Believe It Or Not!. I'm confident it's not true because there's absolutely no mention of Francesca Nortyuege in any source before Ripley's 1929 book came out.

Robert L. Ripley, Believe it or Not!

I've posted my thoughts about Ripley before — that I think he invented many of his stories. See, for example, the post "Clothes for Snowmen" about Madame de la Bresse who was said to have died in 1876, instructing in her will that all her money be used for buying clothes for snowmen. Another Ripley invention, and one that is quite similar to the tale of Francesca Nortyuege. Ripley was evidently amused by the idea of people imposing puritanical demands on their heirs.

Perhaps the most widespread invention from Ripley's 1929 book is the story of Lady Gough's book of etiquette.

This story has been repeated all over the place (google it and see), and again it's an anecdote about an overly prudish character. But as the Faktoider blog notes, Lady Gough never wrote a book on etiquette. Nor did she even exist.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Aug 23, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Censorship, Bluenoses, Taboos, Prohibitions and Other Cultural No-No’s, Inheritance and Wills

Money in the chicken coop

Sounds like Albert didn't want his sisters to know about the money in the chicken coop. Perhaps it was his intention for it all to burn after he died.

Atlanta Journal - Dec 15, 1968

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jul 18, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Money, Inheritance and Wills, 1960s

Man leaves thousands to a stranger, $1 to his wife

When Fred Eggerman died on March 24, 1960, his will left his estate worth approximately $12,000 (about $120,000 in today's money) to the first male child born in Paterson General Hospital on July 2, 1946. He had no idea who that child had been. To his wife he left one dollar.The lucky beneficiary turned out to be high-school student Robert De Boer.

Eggerman's wife filed suit to overturn the will, together with Eggerman's father and brother. They eventually reached a settlement, but it only got them a mere $850. De Boer kept the rest.

Newsday - Apr 22, 1961

New York Daily News - Apr 20, 1961

Based on those details it definitely sounds like Eggerman must a) have been a bit eccentric, and b) have hated his wife. That's how many news articles presented the case. But the article below went into some background details which help to explain what Eggerman did.

For a start, he and his wife had been separated for years and had already worked out a property settlement. So there was no particular reason to leave her more.

As for leaving everything to an unknown child:

Passaic Herald-News - Feb 8, 1962

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jul 12, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Lawsuits, 1960s

Woodbury Rand, cat lover

When Boston attorney Woodbury Rand died in 1944, he left $40,000 to his cat Buster. Out of a $1,000,000 estate, that's not particularly unusual. But what made his will odd was that he disinherited anyone whom he felt hadn't properly appreciated Buster.Buster was only 8 years old when Rand died, but he died the following year. Perhaps of a broken heart?

New York Daily News - Aug 6, 1944

New York Daily News - Dec 30, 1945

Posted By: Alex - Sat May 11, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Cats, 1940s

Estate Willed by Talkie

Video wills have become quite common, but they weren't back in 1931. So the unnamed testator described below was breaking new ground by creating one (or rather, a filmed will).I particularly like the detail that he left instructions on where everyone should sit while watching the film, so that he could look at each person directly from the grave.

Wichita Eagle - Jan 10, 1931

Posted By: Alex - Sat Mar 30, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Law, Movies, 1930s

A year of chocolate

When he died in 1976, John Bostock left money in his will so that every child under five in the village of Westgate-in-Weardale would be given a bar of chocolate once a week for a year.The children in Eastgate-in-Weardale must have felt like they drew the short end of the straw.

Burton Daily Mail - Mar 5, 1976

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 27, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Chocolate, 1970s

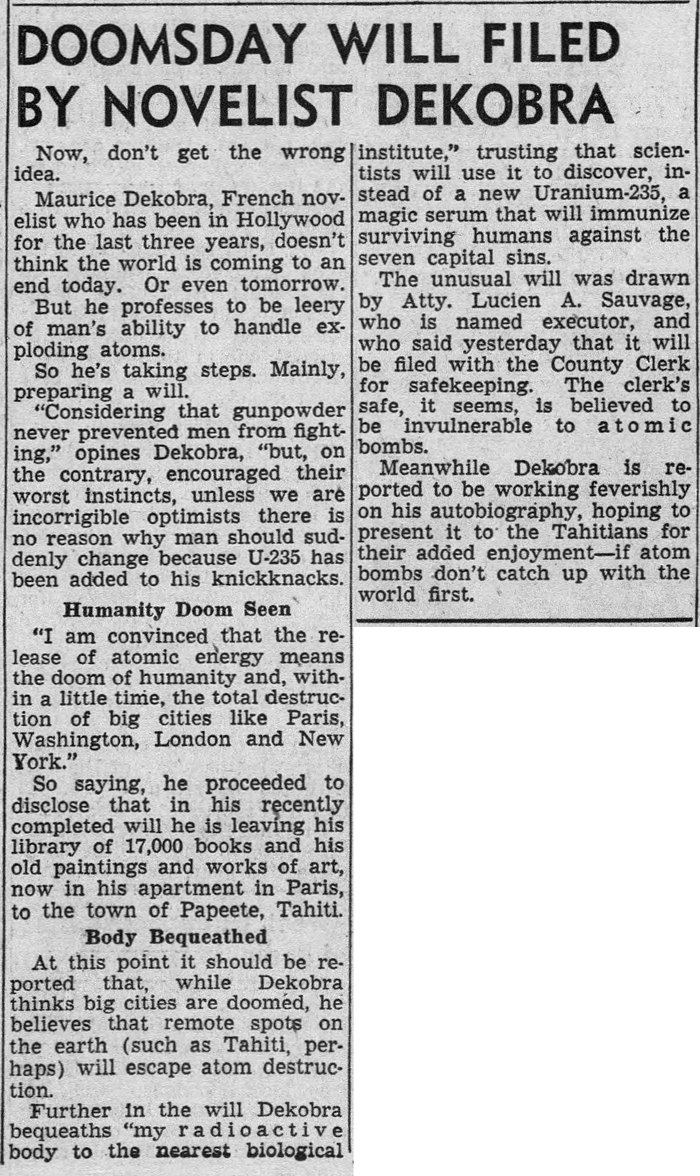

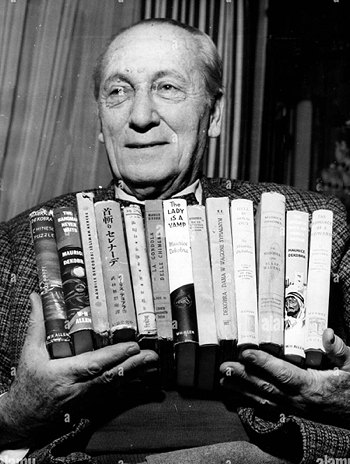

The Doomsday Will of Maurice Dekobra

According to Wikipedia, during the 1920s and 30s Maurice Dekobra was probably the best-known French writer in the world. His most famous book was La Madone des Sleepings (The Madonna of the Sleeping Cars), which according to its Amazon blurb is "one of the first and most influential spy novels of the twentieth century."I hadn't heard of it. This is probably because (again according to Wikipedia) by the 21st Century Dekobra had become a "total unknown."

In 1945, while Dekobra was still near the height of his fame, he drew up an unusual will. He left his entire library of 17,000 books as well as his art collection to the town of Papeete in Tahiti. He did this because he figured that big cities such as Paris and London would probably soon be destroyed by nuclear bombs. But Papeete might survive. Therefore, so might his books.

Dekobra ended up living until 1973. I haven't been able to find out if, by that time, he had changed his will, or if Papeete ever got his books.

Los Angeles Times - Oct 3, 1945

Dekobra in 1965 holding some of his books

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jun 15, 2023 -

Comments (3)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Books

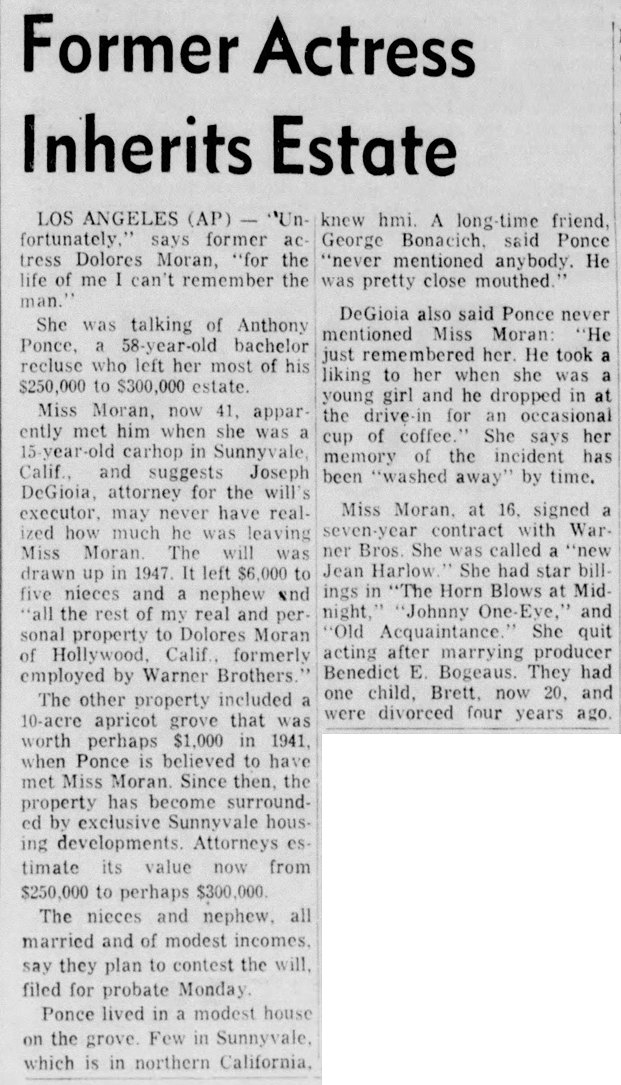

Biggest gratuity ever?

In 1941, when Dolores Moran was 15, she worked as a waitress at a drive-in restaurant in San Jose, California. One day she served a local farmer some coffee and hamburger. The next year Moran left San Jose and moved to Hollywood where she achieved brief fame as an actress.

Dolores Moran. Image source: wikipedia

By the 1960s her acting career had ended. But then, in 1968, Moran learned that the farmer she had served at the drive-in 27 years ago had died, leaving her his apricot orchard valued at around $300,000 (or $2.5 million in today's money).

Moran had no memory of serving the farmer, whose name was Anthony Ponce. Nor had the two ever communicated since then. She said, "for the life of me I can't remember the man." But evidently she had made a big impression on him.

Monroe News Star - Dec 18, 1968

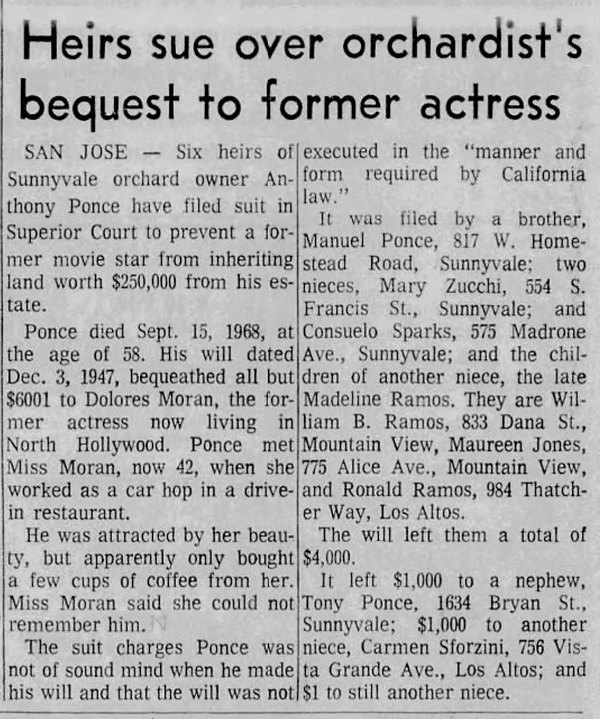

Ponce's relatives contested the will, arguing that he was not of sound mind when he made it. I haven't been able to find out how the case was settled, but I'm guessing Moran got to keep the orchard since it's usually fairly difficult to invalidate a will.

If she did get to keep it, then that would have to count as one of the biggest gratuities of all time. Perhaps the biggest? Especially for an order of coffee and hamburger.

Peninsula Times Tribune - Feb 19, 1969

Posted By: Alex - Thu Apr 06, 2023 -

Comments (3)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Law, Restaurants, Actors

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |