Insects and Spiders

Jiminy Cricket’s Safety Songs

The first song from the album is in the video, but the entire album is here for your listening pleasure.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Apr 27, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Insects and Spiders, Movies, Music, PSA’s, Children, 1950s

man vs. fly

A little over a week ago, I posted about a woman who, in 1985, managed to blow the roof off her house while trying to kill some insects. Now recent news has provided a follow-up:I checked to see if Chuck had ever decided that people destroying their homes while trying to kill insects was a 'No Longer Weird' type of story, and yes, he had! In his Sept 18, 2016 column, he listed the following story under the 'no longer weird' heading:

Posted By: Alex - Wed Sep 09, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Insects and Spiders

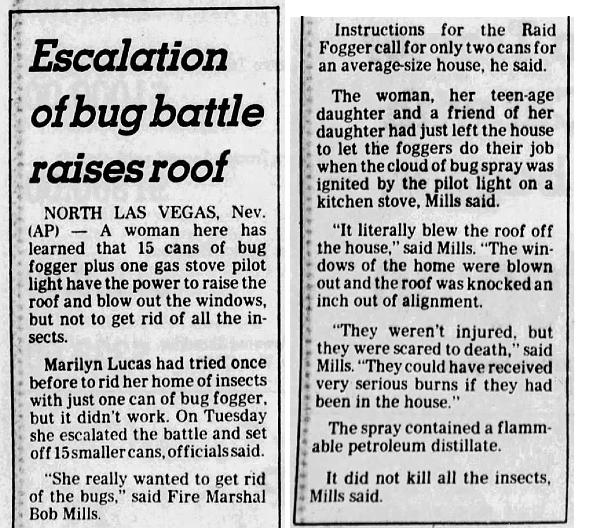

Woman vs. Bugs

October 1985: Deciding that a single can of bug spray hadn't been enough, Marilyn Lucas set off 15 cans simultaneously. The resulting explosion blew the roof off her house. The bugs survived.

Fort Worth Star Telegram - Oct 30, 1985

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 31, 2020 -

Comments (6)

Category: Insects and Spiders, 1980s

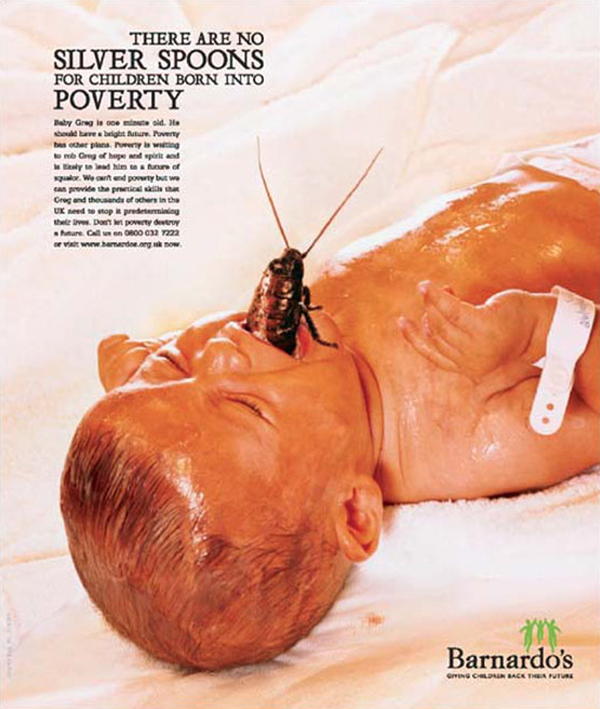

Baby and Cockroach

In 2003, the UK children's charity Barnardo's came out with the ad below. It promptly triggered numerous complaints to the Advertising Standards Authority. Barnardo's argued that it "caused distress for good reason, but the ASA banned the ad anyway, saying it could "cause serious or widespread offense."The ad was subsequently voted one of the top 10 ads of 2003 by Campaign magazine.

Of course, the charity must have known it was likely the ad would get banned, but evidently figured the controversy would attract more attention to their message than something more subdued.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Aug 15, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Babies, Charities and Philanthropy, Insects and Spiders, Advertising, Nausea, Revulsion and Disgust

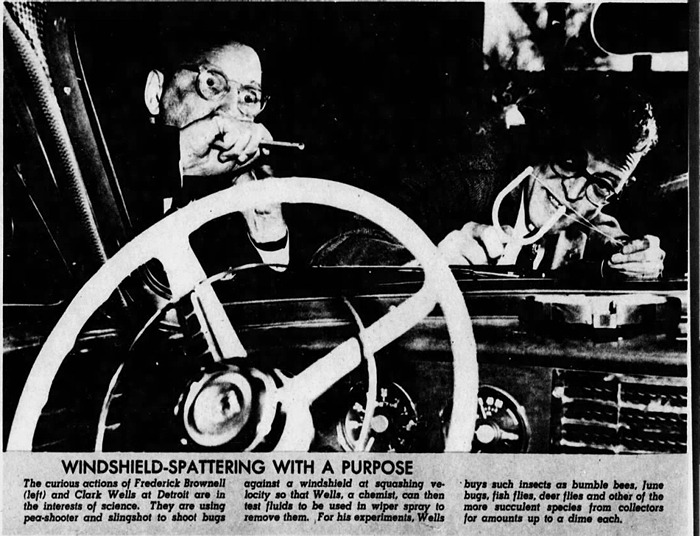

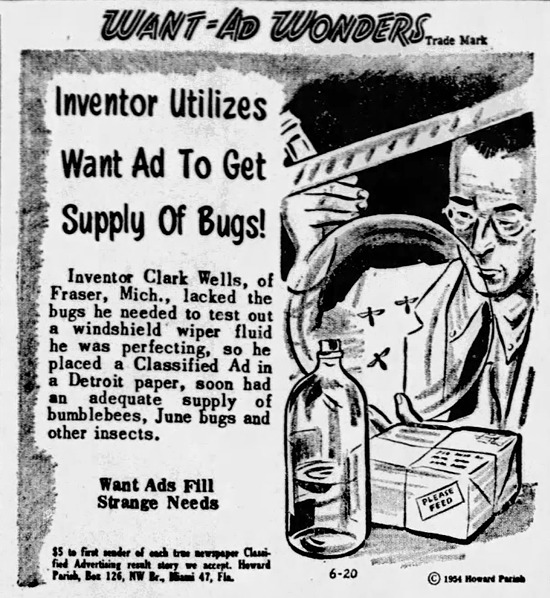

The science of removing bugs from windshields

When you clean bugs off your car's windshield, think of Detroit researcher Clark Wells who spent his career figuring out how best to do this.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch - Mar 22, 1953

The curious actions of Frederick Brownell (left) and Clark Wells at Detroit are in the interests of science. They are using pea-shooter and slingshot to shoot bugs against a windshield at squashing velocity so that Wells, a chemist, can then test fluids to be used in wiper spray to remove them. For his experiments, Wells buys such insects as bumble bees, June bugs, fish flies, deer flies and other of the more succulent species from collectors for amounts up to a dime each.

Huntsville Times - June 20, 1954

Posted By: Alex - Sat Aug 08, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Insects and Spiders, Science, 1950s, Cars

Tarantula Bedding

Available from retailer Ggtrends.An appropriate gift for the arachnophile in your life.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jul 19, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Furniture, Insects and Spiders

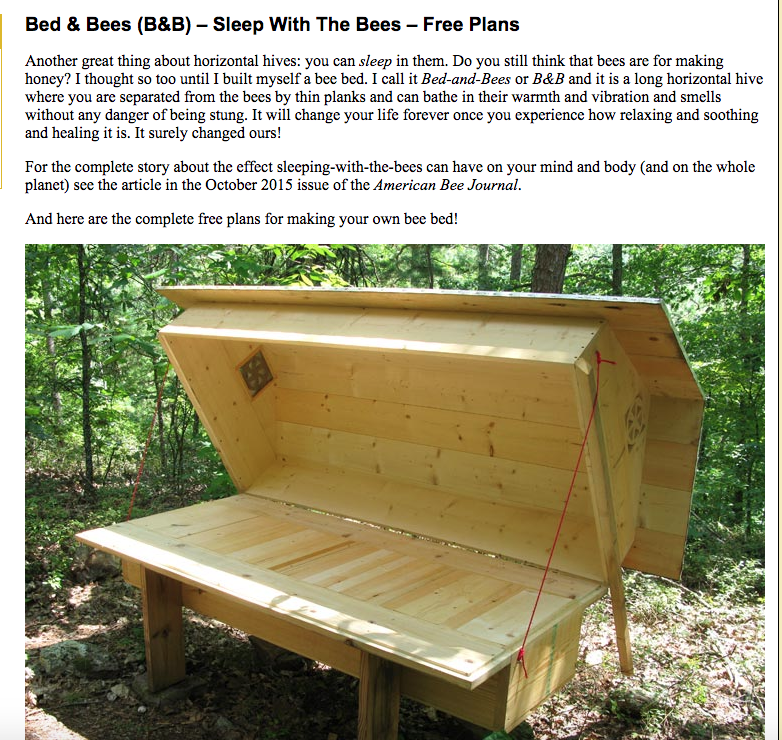

The Bee Bed

Get your free plans here!

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jun 23, 2020 -

Comments (9)

Category: Death, Domestic, Excess, Overkill, Hyperbole and Too Much Is Not Enough, Insects and Spiders

The Boll Weevil Monument

The Wikipedia Page.

Posted By: Paul - Sun May 31, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Agriculture, Insects and Spiders, Regionalism, Statues and Monuments

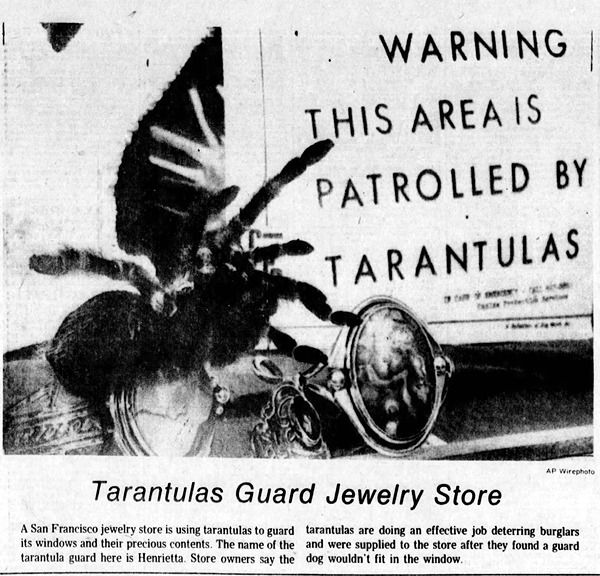

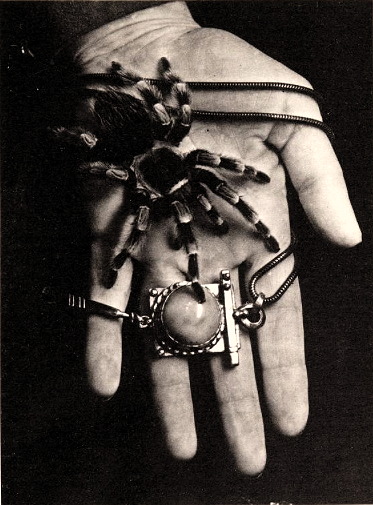

Tarantula security guards

In the mid-1970s, there was a fad among jewelry stores to use tarantulas as security guards. Stores claimed it helped prevent thefts, although tarantulas aren't going to do much to stop a thief, besides looking scary. Rattlesnakes, I imagine, might work better.

La Crosse Tribune - July 19, 1975

Posted By: Alex - Fri May 08, 2020 -

Comments (5)

Category: Crime, Insects and Spiders, 1970s

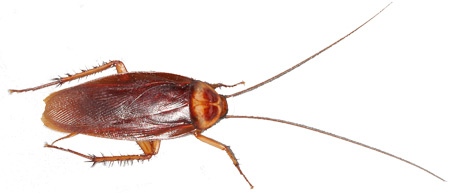

Removing cockroaches from the ear: a comparative study

Back in 1985, doctors at an emergency room in Pittsburgh were presented with a woman who had somehow got cockroaches in both her ears. The doctors immediately decided this presented a rare opportunity to do a comparative study on methods of removing cockroaches from ears. They reported on their results in the New England Journal of Medicine, "Removing Cockroaches from the Auditory Canal: Controlled Trial," 1985, 312(18): 1197.A patient recently presented with a cockroach in both ears. The history was otherwise noncontributory. We recognized immediately that fate had granted us the opportunity for an elegant comparative therapeutic trial. Having visions of a medical breakthrough assuredly worthy of subsequent publication in the Journal, we placed the time-tested mineral oil in one ear canal. The cockroach succumbed after a valiant but futile struggle, but its removal required much dexterity on the part of the house officer. In the opposite ear we sprayed 2 per cent lidocaine solution. The response was immediate; the roach exited the canal at a convulsive rate of speed and attempted to escape across the floor. A fleet-footed intern promptly applied an equally time-tested remedy and killed the creature using the simple crush method.

However humble the method, and despite our small study population, we think we have provided further evidence justifying the use of lidocaine for the treatment of a problem that has bugged mankind throughout recorded history.

K. O'Toole, M.D.

P.M. Paris, M.D.

R.D. Stewart, M.D.

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

R. Martinez, M.D.

Louisiana State University

A subsequent letter to the journal noted a limitation of their report. In many cases, cockroaches get stuck in the ear canal. In which case, they can't just scurry out when sprayed with lidocaine. However, the correspondents offered a method of dealing with this situation. ("Removing cockroaches from the auditory canal: a direct method" NEJM. 1989. 320(5): 322).

As we burst into the room, we could see the young woman writhing from the combined sensations of movement and pain in her ear canal. One of us tok a look, confirming the nurse's diagnosis, while the other filled a 3-cc syringe with 2 percent lidocaine solution. With hurried anticipation we sprayed the drug briskly into the ear canal and quickly jumped back, fully expecting the beast to come hurtling forth at first contact with the noxious substance.

Nothing. "Increase the dosage," we shouted, filling a 10-cc syring. Still nothing. "Get that sucker outa my ear!" the patient screamed. What a brilliant idea! We grabbed a 2-mm metal suction tip and attached it to a wall suction apparatus with a negative pressure of 120 cm of water. Then we gently passed the tip into the ear canal, taking care not to occlude the canal and risk tympanic-membrane barotrauma. Shloop! "Got him!" we exulted. Sure enough, there he was, plastered to the suction tip like a fly to flypaper. After a repeat examination of the canal and a few drops of Cortisporin solution, the patient was on her way.

We recommend suction as a safe and efficacious method for removing insects from the ear canal when other methods fail.

Jonathan Warren, M.D.

Leo C. Rotell, M.D.

State University of New York

Health Science Center

Posted By: Alex - Wed Apr 29, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Insects and Spiders, Medicine, 1980s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |