Insects and Spiders

Killer Bee Monument

Source, with info.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Mar 17, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Enlargements, Miniatures, and Other Matters of Scale, Insects and Spiders, Regionalism, Statues and Monuments

Albert in Blunderland

This'll get you hep to the real meaning of "socialism."

Posted By: Paul - Wed Mar 11, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Dreams and Nightmares, Government, Insects and Spiders, Money, Work and Vocational Training, Cartoons

Insect Butter

The latest effort to convince everyone to eat insects comes from Ghent University in Belgium where researchers tested whether people could tell the difference between waffles, cookies, and cake made with butter, versus butter combined with fat from black soldier fly larvae.They claimed that a mixture of 75% butter and 25% insect fat was undetectable to people. And, in some cases, even a 50/50 mix of butter/insect fat couldn’t be detected.

So they’re hopeful that bakery products made with insect butter may soon be on shelves. They note:

More info: Ghent University

Posted By: Alex - Wed Feb 19, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Insects and Spiders

Live Beetle Brooch

A living beetle, encased in a silver girdle, worn as a brooch. It was said to be “the rage of high-fashion Europe” in the early 1960s. With proper care, this living brooch supposedly would survive from two to six years.I don't think a beetle would suffer by being worn as a brooch. Would it even care if it was being fed well? Even so, I'm guessing that living jewelry wouldn't go over well nowadays. Though that's no great loss to the world of fashion.

Toronto National Post - Dec 8, 1962

Posted By: Alex - Mon Feb 10, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Insects and Spiders, Jewelry, 1960s

Wasp Face

In 1933, Miss Winifred Mondeau found on her property a wasp’s nest that resembled a human face.

Newport News Daily Press - July 6, 1933

Some googling reveals that there’s a minor genre of wasp (and hornet) nests that resemble faces. The one below, for example, was found in the yard of Brenda Montgomery in 2017. Though it's not as good as the one from 1933.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Feb 08, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Insects and Spiders, 1930s, Pareidolia

Fly-Operated Turtle

Patent No. 1,591,905, granted to Oscar C. Williams of San Diego, CA in 1926, described this curious device.It was a toy turtle. Its body was made of wood or aluminum, while the head, legs, and tail were made from lightweight cork. The user was supposed to insert several flies into the hollow body of the turtle. Their agitations once inside, as they sought to escape, would then cause the movable parts of the turtle to wag from side to side, as if the creature was alive.

I can see several drawbacks. First, you would have to catch some flies and maneuver them (alive) into the turtle. This was done by squeezing them through the leg hole. Handling a fly in this way seems like it could be a challenge.

And once in there, I imagine you'd have to wait until the flies died to get them back out. So, essentially, it was a fly torture device.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Dec 22, 2019 -

Comments (4)

Category: Insects and Spiders, Inventions, Patents, Toys, 1920s

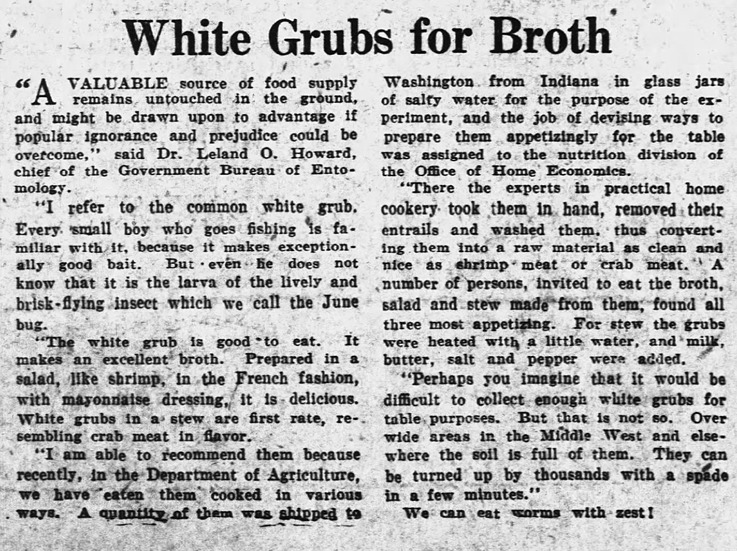

White Grub Broth

The holiday season is upon us. So, what better time to experiment with white grub broth in your cooking. Switch out the usual chicken stock for some white grub broth, and see what your guests think. Or just serve it on its own!

Sioux City Journal - Aug 6, 1922

"I refer to the common white grub. Every small boy who goes fishing is familiar with it, because it makes exceptionally good bait. But even he does not know that it is the larva of the lively and brisk-flying insect which we call the June bug.

"The white grub is good to eat. It makes an excellent broth. Prepared in a salad, like shrimp, in the French fashion, with mayonnaise dressing, it is delicious. White grubs in a stew are first rate, resembling crab meat in flavor.

"I am able to recommend them because recently, in the Department of Agriculture, we have eaten them cooked in various ways. A quantity of them was shipped to Washington from Indiana in glass jars of salty water for the purpose of the experiment, and the job of devising ways to prepare them appetizingly for the table was assigned to the nutrition division of the Office of Home Economics.

"There the experts in practical home cookery took them in hand, removed their entrails and washed them, thus converting them into a raw material as clean and nice as shrimp meat or crab meat. A number of persons, invited to eat the broth, salad and stew made from them, found all three most appetizing. For stew the grubs were heated with a little water, and milk, butter, salt and pepper were added.

"Perhaps you imagine that it would be difficult to collect enough white grubs for table purposes. But that is not so. Over wide areas in the Middle West and elsewhere the soil is full of them. They can be turned up by thousands with a spade in a few minutes."

We can eat worms with zest!

Typical white grub (source: University of Florida entomology & nematology)

Posted By: Alex - Fri Dec 13, 2019 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Insects and Spiders

The Lice-Infested Underwear Experiment

During World War II, millions of men served their country by fighting in the military. Hundreds of thousands of others worked in hospitals or factories. And thirty-two men did their part by wearing lice-infested underwear.

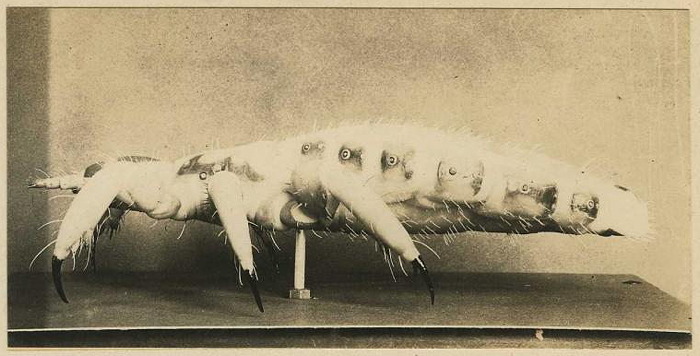

Model of a body louse, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

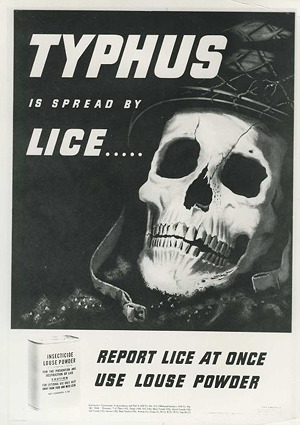

World War II public health warning

Source: Nat. Museum of Health & Medicine

In an attempt to prevent this, the Rockefeller Foundation, in collaboration with the federal government, funded the creation in 1942 of a Louse Lab whose purpose was to study the biology of the louse and to find an effective means of preventing infestation. The Lab, located in New York City, was headed by Dr. William A. Davis, a public health researcher, and Charles M. Wheeler, an entomologist.

The first task for the Louse Lab was to obtain a supply of lice. They achieved this by collecting lice off a patient in the alcoholic ward of Bellevue Hospital. Then they kept the lice alive by allowing them to feed on the arms of medical students (who had volunteered for the job). In this way, the lab soon had a colony of thousands of lice. They determined that the lice were free of disease since the med students didn't get sick.

Next they had to find human hosts willing to serve as subjects in experiments involving infestation in real-world conditions. For this they initially turned to homeless people living in the surrounding city, whom they paid $7 each in return for agreeing first to be infected by lice and next to test experimental anti-louse powders. Unfortunately, the homeless people proved to be uncooperative subjects who often didn't follow the instructions given to them. Frustrated, Davis and Wheeler began to search for other, more reliable subjects.

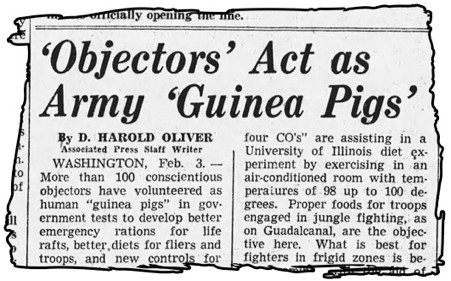

The Vancouver Sun - Feb 3, 1943

In theory, the COs were always given a choice about whether or not to serve as guinea pigs. In practice, it wasn't that simple. Controversy lingers about how voluntary their choice really was since their options were rather limited: be a guinea pig for science, or do back-breaking manual labor. But for their part, the COs have reported that they were often eager to volunteer for experiments. Sensitive to accusations that they were cowardly and unpatriotic, serving as a test subject offered the young men a chance to do something that seemed more heroic than manual labor.

Eventually COs participated in a wide variety of experiments, but Davis and Wheeler were the very first researchers to use American COs as experimental subjects. And they planned to infest these volunteers with lice.

More in extended >>

Posted By: Alex - Wed Sep 04, 2019 -

Comments (5)

Category: Health, Insects and Spiders, Experiments, Underwear, 1940s

Project Capricious

During World War II, the OSS (precursor to the CIA) hatched a plan to defeat General Rommel's Afrika Korps by using synthetic goat poop. The idea was to drop huge amounts of pathogen-laced pseudo-poop over African towns. Local insects would be attracted to the stuff and would then carry the pathogens to Rommel's troops. However, before the plan could be carried out, Rommel's troops were withdrawn from the area and sent to Russia.Jeffrey Lockwood tells the story in more detail in his book Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War.

The plan was to weaken the enemy forces by using flies to spread a witch's brew of pathogens. Given the agency's inability to rear an army of flies, [OSS Research Director] Lovell decided to conscript the local vectors...

Lovell was a chemist, but he'd been out of the laboratory often enough to know that flies love dung. And with a bit of research, he discovered a key demographic fact: There were more goats than people in Morocco — and goat are prolific producers of poop. Lovell now had the secret formula: microbes + feces + flies = sick Germans. Now all he needed was a few tons of goat droppings as a carrier for laboratory-cultured pathogens.

The OSS collaborated closely with the Canadian entomological warfare experts to launch one of the more preposterous innovations in the history of clandestine weaponry: synthetic goat dung. Of course flies are no fools; they won't be taken in by any old brown lump. So the OSS team added a chemical attractant. The nature of this lure is not clear, but a bit of sleuthing provides some clues.

Allied scientists might have crafted a chemical dinner bell by collecting and concentrating the stinky chemicals that we associate with human feces (indole and the appropriately named skatole). While these extracts would have worked, the more likely attractant was a blend of organic acids, some of which had been known for 150 years. Two of the smelliest of these are caproic and caprylic acids, which, by no coincidence, derive their names from caprinus, meaning "goat." Etymologically as well as entomologically astute, Lovell named the operation Project Capricious. So with a scent to entice the flies, Lovell's team then coated the rubbery pellets in bacteria to complete the lures.

All the Americans had to do was drop loads of pathogenic pseudo-poop over towns and villages where the Germans were garrisoned, and millions of local flies would be drawn to the bait, pick up a dose of microbes, and then dutifully deliver the bacteria to the enemy. Lovell worried about keeping the operation clandestine. The Moroccans had to be persuaded that finding goat droppings on their roofs the morning after Allied aircraft flew over was a sheer coincidence. Presumably a good disinformation campaign can dispel almost any suspicion, or, as Lovell intimated, if the plan succeeded there would be very few people in any condition to raise annoying questions about fecal pellets on rooftops...

In the end, however, Lovell didn't have to worry about getting caught by either friends or foes, as the secret weapon was never deployed. Just as the OSS was gearing up to launch the sneak attack, the German troops were withdrawn from Spanish Morocco. They might well have preferred to take their chances with pathogen-laden flies, given that Hitler was sending them to the bloody siege of Stalingrad.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jul 20, 2019 -

Comments (5)

Category: Insects and Spiders, Military, War, Weapons, Excrement, 1940s

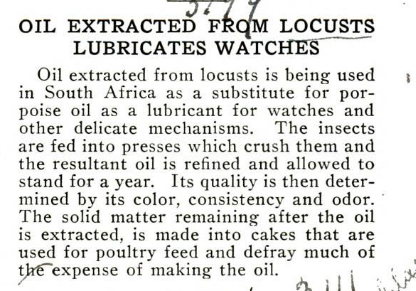

Porpoise Oil or Locust Oil: Your choice!

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Mar 29, 2019 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Insects and Spiders, Technology, 1920s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |