Inventions

The Nothing Box

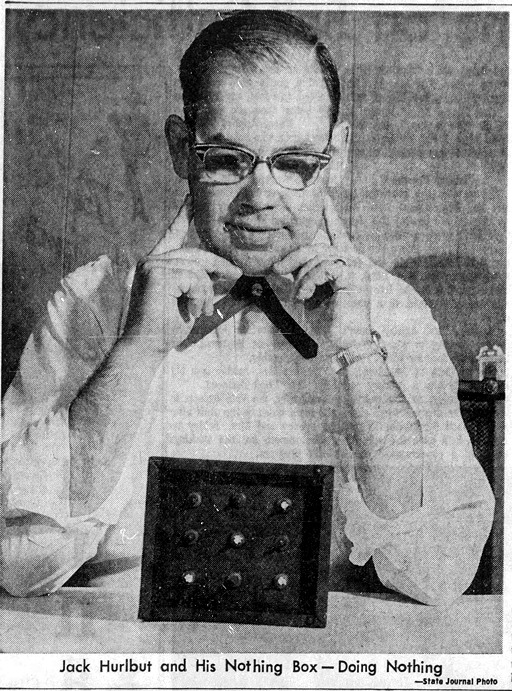

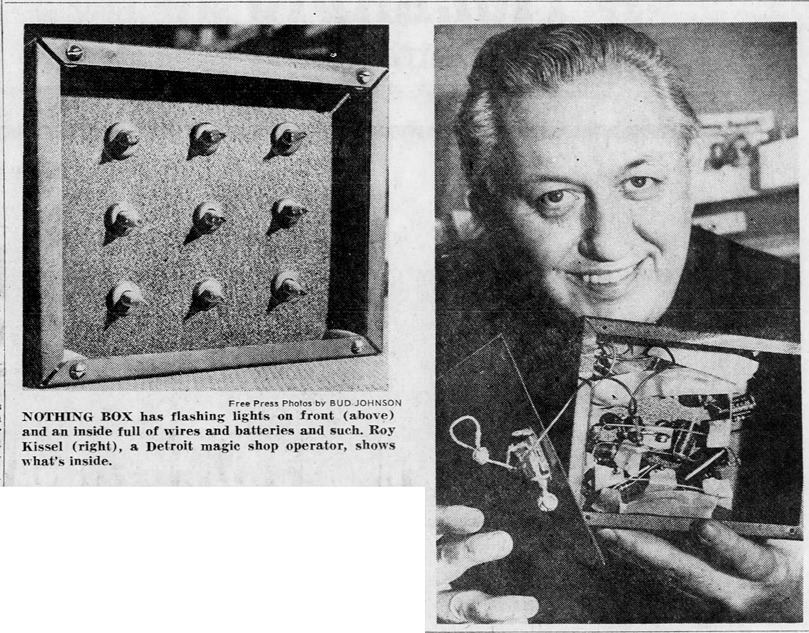

A gag gift from the early 1960s, created by inventor Jack Hurlbut: "When a button is pressed the lights flash, the dials spin, the switches turn—and nothing happens."It briefly made headlines in 1965 when a man took one with him on a flight, and was promptly detained on the suspicion that he was carrying a bomb.

The Nothing Box is another one of those vintage curiosities that seem to have completely disappeared. I can't find any evidence that one of them still exists.

Wisconsin State Journal - May 18, 1964

Detroit Free Press - Dec 28, 1965

Detroit Free Press - Dec 28, 1965

Posted By: Alex - Fri Feb 21, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Inventions, 1960s

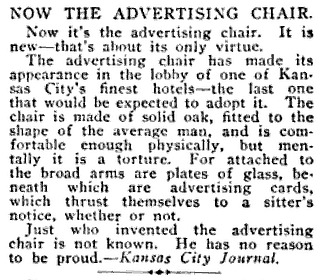

Advertising Chairs

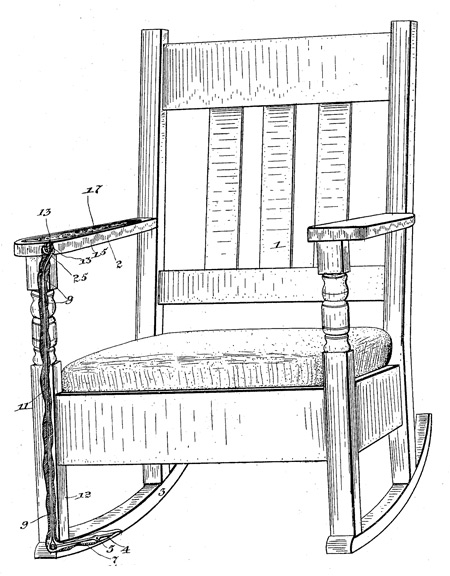

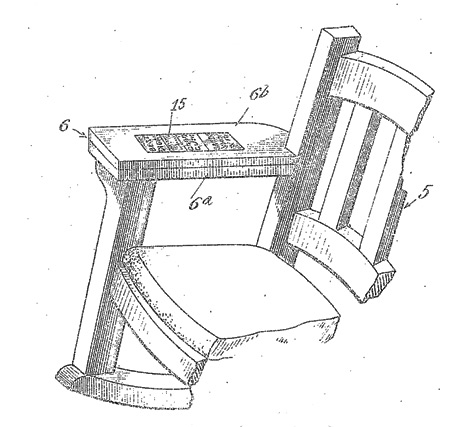

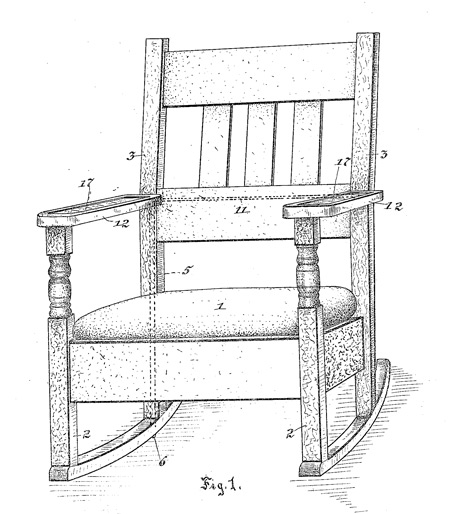

Back in 2018, Paul posted about an "advertising chair" patented in 1910. As a person rocked in it, advertisements scrolled in the armrests.

Patent No. 958,793 (1910)

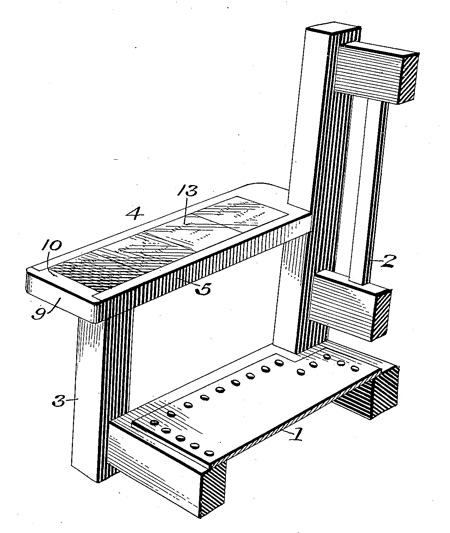

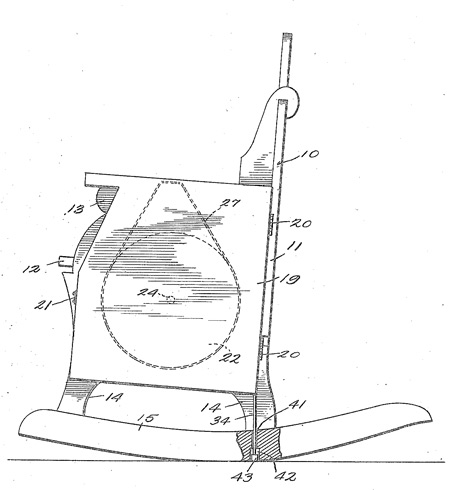

I recently discovered that this invention wasn't a one-off. In the early twentieth century, inventors were actively competing to perfect advertising chairs and inflict them on the public. I was able to find four other advertising chair patents (and there's probably even more than this). To my untrained eye, they all look very similar, but evidently they were different enough to each get their own patent.

Patent No. 934,856 (1909)

Patent No. 993,397 (1911)

Patent No. 1,094,154 (1914)

Patent No. 1,441,911 (1923)

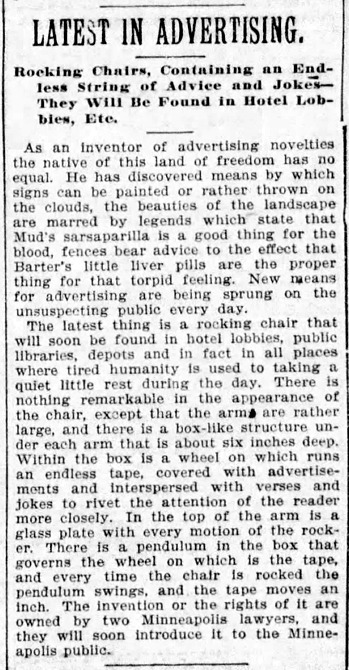

A newspaper search brought up an 1895 article that described advertising chairs as the "latest in advertising." It also explained that the concept was to put these chairs in various places where there were captive audiences, such as "hotel lobbies, public libraries, depots and in fact in all places where tired humanity is used to taking a quiet little rest during the day."

Minneapolis Star Tribune (Dec 8, 1895)

But although entrepreneurs may have been keen to build advertising chairs, the public was evidently far less enthusiastic about them. An editorial in the Kansas City Journal (reprinted in Printer's Ink magazine - Jan 2, 1901) described an advertising chair as "comfortable enough physically, but mentally it is a torture... Just who invented the advertising chair is not known. He has no reason to be proud."

There must have been a number of these advertising chairs in existence, but I'm unable to find any surviving examples of them. Searching eBay, for instance, only pulls up chairs with advertisements printed on them.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Feb 18, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Furniture, Inventions, Patents, Advertising

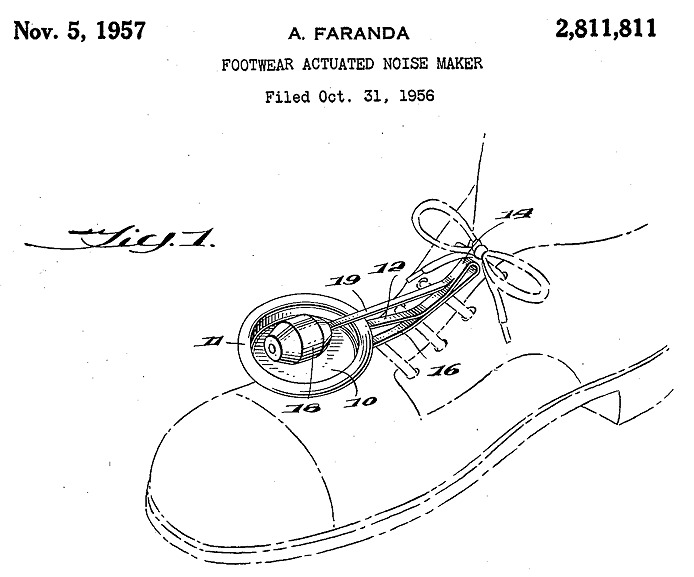

Shoe Gongs

Anthony Faranda of Yonkers, NY worried that children didn't like wearing rubber-soled shoes because they made no noise when walking on a pavement. So, he invented a shoe gong. Or, as he called it, a "footwear actuated noise maker." He patented it in 1957.It was a disc and clapper that could be worn over shoes. He explained: "The arrangement is such that upon normal walking steps or running strides the clapper is activated to make noise and thereby promote the interest of children in wearing shoes with soles that do not make an audible sound in engaging firm or rigid surfaces."

Maybe kids would have liked these, but not, I imagine, their parents.

He assigned the patent to the NY advertising agency McCann-Erickson. It's unclear what plans they might have had for these things.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Feb 16, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Shoes, 1950s

Donkey Bike

Posted By: Paul - Fri Feb 14, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Bicycles and Other Human-powered Vehicles, Inventions, 1960s

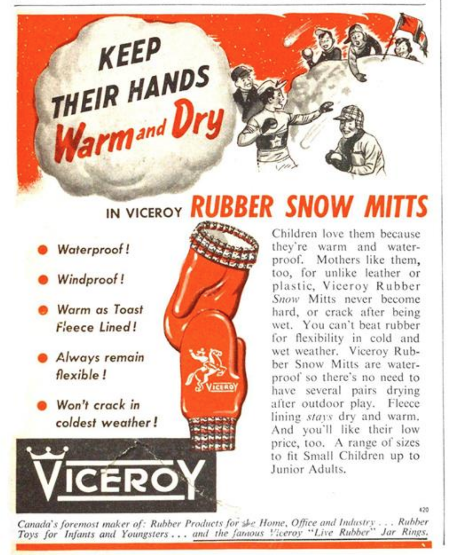

Rubber Snow Mitts

There's a good reason these never caught on: I'm sure the wearer's hands were as clammy as dead fish within seconds of wearing them.Source.

Even the modern version that appears next has some breathable fabric, and is specially for work, not snowball fights.

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Feb 12, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Inventions, Seasonal, Pain, Self-inflicted and Otherwise, Skin and Skin Conditions

Throwing Animals for Taking Death Leaps

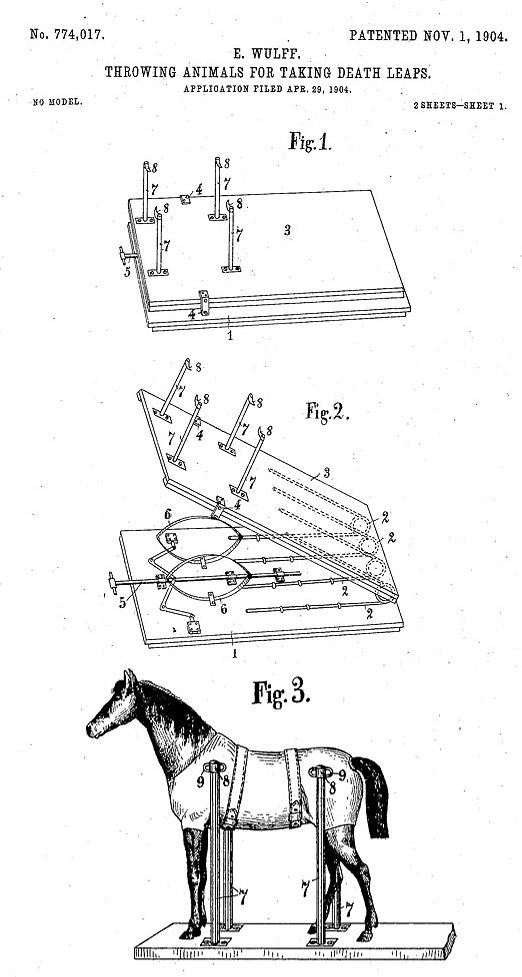

Circus proprietor Edward Wulff patented a curious device in 1904. It was an apparatus that catapulted animals upwards. It had the rather alarming title, "Throwing Animals For Taking Death Leaps" (Patent No. 774,017). Wulff claimed it could throw "horses, elephants, monkeys, &c.." The patent illustration shows a horse, so these were evidently the primary animal being thrown.

The device was relatively straight-forward. The animals were placed in a harness that held them on top of a spring-powered platform. The release of the springs then flung the animals upwards. Wulff emphasized that his apparatus was designed, via the harness, to place the projecting force on the full body of the animal, rather than just their legs. He seemed to feel that this was a safer, more humane method of throwing animals.

Wulff explained that this device was designed to be used as part of a circus stunt known as "a death leap or so-called 'salto-mortale.'" But he didn't offer any further explanation about the nature of the stunt or how far the animals were flung. And I couldn't locate any descriptions of this stunt in other sources. All the references to a 'death leap' stunt that I came across involved human trapeze artists, not animals. So I was about to conclude that the stunt would have to remain a mystery until I got the idea to check if Wulff had filed the patent in any other countries. Sure enough, there was a British version of the patent, and while its text was almost identical, it had a different title that explained the nature of the stunt:

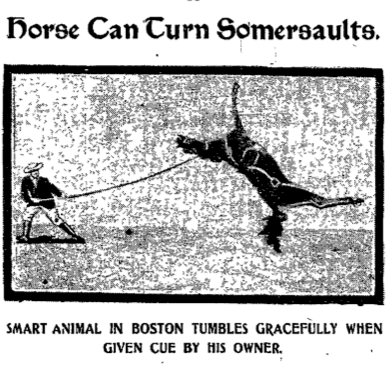

So Wullf's apparatus was evidently designed to somersault animals. Not simply to catapult them upwards. This made me recall something I posted here on WU back in 2012. It was a brief item that appeared on the front page of the Washington Post's 'Miscellany Section' on April 21, 1907, titled 'Horse Can Turn Somersaults.' At the time, this random reference to a somersaulting horse totally baffled me. I even suspected it was a hoax. But now it makes sense. It must have been a circus stunt. Perhaps it even made use of Wulff's invention. I can't find any evidence that Wulff's circus was in Boston in April 1907, but it was in New York in December of that year.

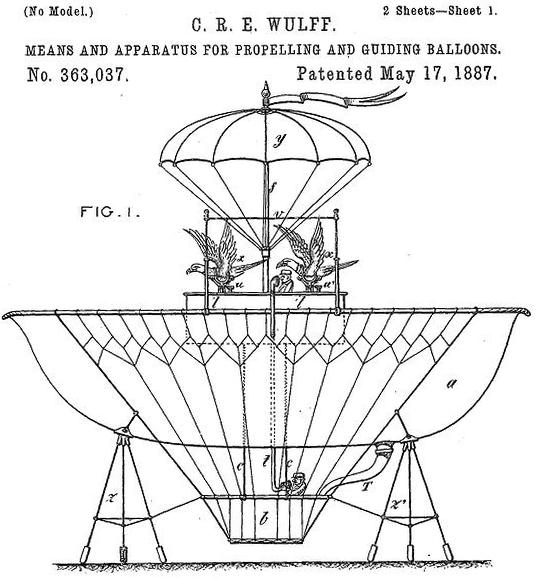

Wulff, it turns out, was the author of another odd patent, granted to him in 1887. The patent was titled, "Means and apparatus for propelling and guiding balloons." He intended to use birds such as "eagles, vultures, condors, &c" to guide balloons. The birds would be attached to the balloon by a harness, and an aeronaut would then force them to fly in the desired direction, thereby propelling the balloon.

This patent has received quite a bit of attention, because there's a lot of interest in the history of early attempts at flying machines. Knowing that Wulff was a circus proprietor, I wonder if he intended his eagle-guided balloon to be used as part of a circus act, rather than as a practical flying machine.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Feb 09, 2020 -

Comments (6)

Category: Animals, Inventions, Patents, ShowBiz, 1900s

Lew Lehr’s Inventions

His Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Feb 09, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Inventions, Chindogu, Movies, Twentieth Century

Suntan Suzy Doll

Suntan Suzy was a doll that would develop a tan if you put her in the sunlight. Back in the shade, her tan would fade. She came on the market in 1962, but lasted only one season. As far as I can tell, she was the only doll that has ever had the ability to tan.

Arizona Republic - Nov 23, 1962

image source: worthpoint

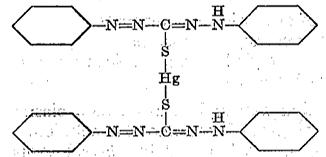

The chemistry responsible for producing the tanning effect is described in Patent No. 2,921,407 (Jan 19, 1960) – “Simulating Sunburning Toy Dolls and Figurines”:

1550 grams of a high molecular weight polyvinyl chloride polymer, in powdered form, were dispersed in this solution by stirring for ten to fifteen minutes. The latter material was specifically Bakelite Company QYNV polymer. Thus a plastisol formulation containing the phototropic dye dissolved in the liquid dioctyl phthalate (plasticizer phase) was obtained. About 120 grams of this plastisol formulation were then poured into a two piece steel mold, this having its inner surface previously coated with a silicone oil release film. This was then placed in an oven at 140 degrees centigrade and held at this temperature for eight minutes to allow solution of the polyvinyl chloride polymer phase. The mold and contents were then removed from the oven, cooled to room temperature, and the now solid form of the doll figure removed.

The figure thus produced was transparent and red in color. Upon exposure to sunlight a progressive darkening to a brown, then blue-black color occurred during a period of about three to four minutes, simulating a “sunburning” effect. When the doll was shielded from the sun a return to the original color took place, being visually complete after a period of eight to ten minutes. This action was repeatable with no detectable change in functional characteristics being noted after several dozen cycles.

It seems like an interesting gimmick for a doll. Curious it never caught on.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Feb 07, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Toys, 1960s

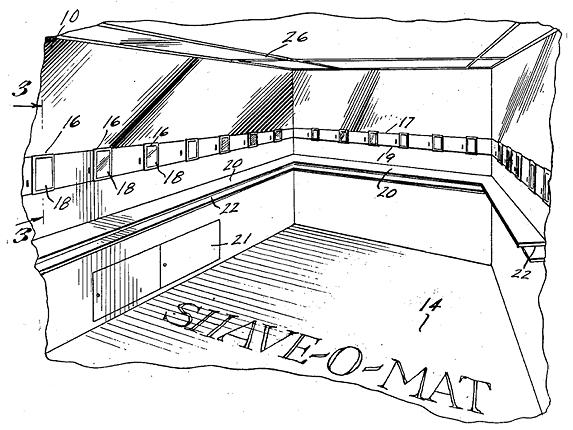

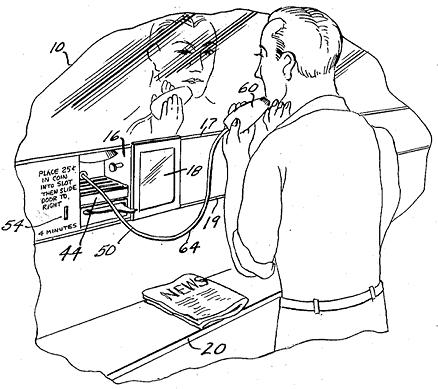

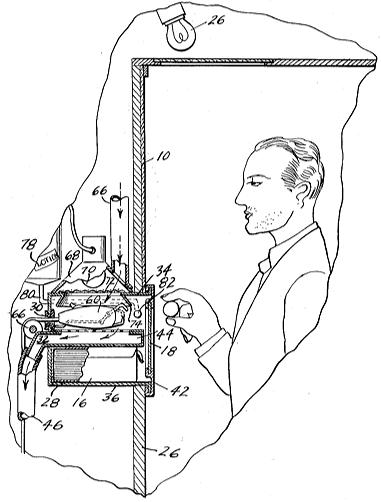

Shave-O-Mat

Harry Thalheim believed that “a need has existed for a long time for a shaving emporium where people may shave cheaply and rapidly at all hours of the day and night.” So, in 1964 he patented the Shave-O-Mat (US Patent No. 3,120,886). It was a coin-operated shave-yourself establishment, open 24 hours a day.Did this address some kind of market need in the 1960s? Were there men who, in the middle of the night, really wanted to shave but couldn’t?

I'm guessing not, because, as far as I can tell, Thalheim's Shave-O-Mat never opened.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Feb 02, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Inventions, Patents, 1960s, Hair and Hairstyling

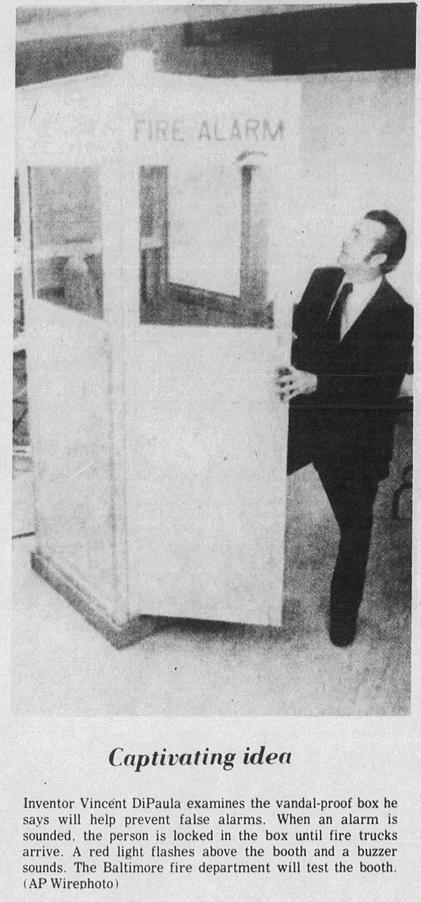

Fire Alarm Trapper

False alarms are a big problem for fire departments, but Vincent DiPaula figured he had a solution. In 1973, he invented a fire alarm ‘trapper’. It looked like a phone booth. If someone wanted to pull the fire alarm, they first had to enter the booth and close the door. Then, when they pulled the alarm, they would be locked inside the booth until the fire department arrived.DiPaula figured this would deter pranksters. The obvious problem (which, I assume, is why his invention failed to be adopted) is that in the event of a real fire, it would also trap a legitimate alarm-ringer inside the burning building.

Fremont News-Messenger - Nov 27, 1973

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jan 27, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Inventions, 1970s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |