Inventions

Helmfon

Design company Hochu Rayu has come up with a noise-blocking helmet for office workers. From their website:Our main idea was to create a tool, which helps fully concentrate on working project, get some personal space and doesn’t allow office noise kill person’s productiveness.

It reminds me of the isolator helmet invented by Hugo Gernsback, back in 1925. (See Laughing Squid for more details).

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jul 11, 2017 -

Comments (6)

Category: Inventions

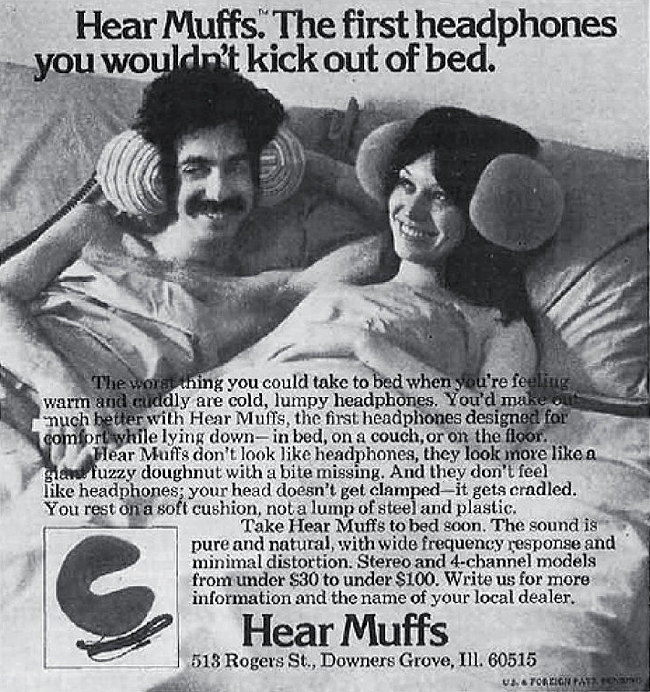

Hear Muffs

Straight out of the 70s. Hear Muffs were the invention of Stephen Hanson of Downers Grove, Illinois. They were headphones encased in a wraparound foam pillow, that came with a washable velour cover.Hanson started selling them in 1972, but by around 1977 the product seems to have been discontinued. Perhaps because you'd only want to wear them in bed. And even then, it was probably difficult to lie on your side while wearing them.

Honolulu Star Bulletin - Aug 16, 1974

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jul 06, 2017 -

Comments (3)

Category: Inventions, 1970s

Refrigerated Camels

Instead of using refrigerated trucks to deliver medical supplies to people who live in the deserts of Africa, inventors have built solar-powered refrigerators that can be carried by camels, and so the medicines are delivered via refrigerated camel.Apparently it wasn't that easy to build a camel-carried refrigerator. It had to be lightweight, but also sturdy enough to survive the motion of being on the camel as well as the extreme desert conditions.

More info: ABC News, inhabitat.com

Posted By: Alex - Wed May 31, 2017 -

Comments (4)

Category: Animals, Inventions, Medicine, Transportation, Africa

“Follow Me” Cooler

Engineers have created a cooler that will follow you wherever you go. Science marches on!More info at hackster.io.

Posted By: Alex - Thu May 25, 2017 -

Comments (2)

Category: Inventions

Holcombe’s Mechanical Partner

I'd like to see this gadget in action. Unfortunately I can't find any videos of it.It doesn't seem to have survived past 1954.

LA Times - July 1, 1954

Posted By: Alex - Sun May 07, 2017 -

Comments (4)

Category: Inventions, 1950s, Dance

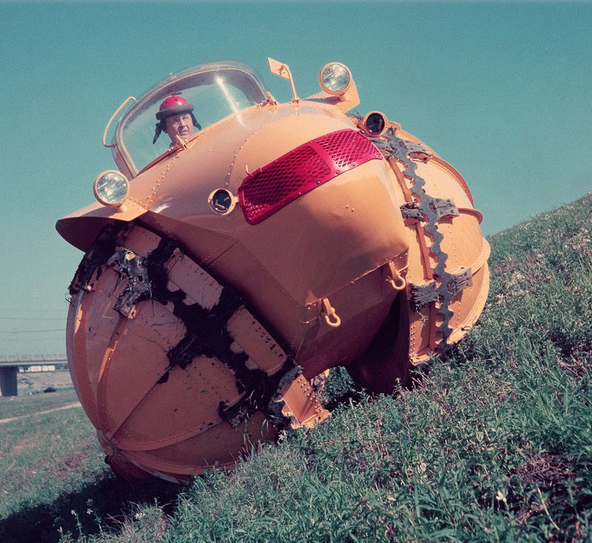

The Rhino

More info here.

1954 coverage here.

Posted By: Paul - Thu May 04, 2017 -

Comments (0)

Category: Inventions, Motor Vehicles, 1950s

The Sex Detector

The Sex Detector made its debut around 1920. It was a gadget, sold by "Sex-Detector Laboratories," that promised to be able to detect the gender of an egg — or any piece of biological matter whose sex one might want to find out (oysters, butterflies, caterpillars, beetles, worms). It supposedly even worked on blood. So police could use it to discover the sex of a criminal.It was basically an empty rifle shell suspended on a piece of string. When held over an egg (or whatever) it would reveal through the direction of its motion the sex of the chick inside.

It was probably more accurately described as an idiot detector... the idiot being the one holding the string.

For a while it was heavily advertised in poultry journals, but when inspectors at the U.S. Dept of Agriculture investigated the efficacy of the device, they found it to be useless. It worked no better than a piece of cardboard attached to a thread. Advertisements for the product were banned.

Wilmington Evening Journal - May 4, 1928

Williams News - July 8, 1921

San Francisco Chronicle - Oct 17, 1920

St. Louis Post-Dispatch - Feb 5, 1922

Posted By: Alex - Tue Apr 25, 2017 -

Comments (2)

Category: Inventions, 1920s

The Dimple Maker

Invented by Mrs. E. Isabella Gilbert in 1936 (although I think similar gadgets had been on the market before). They came with these instructions: "Wear dimplers five minutes at a time, two or three times a day, while dressing, resting, reading or writing. Look into the mirror and laugh. There will be a semblance of a line where you should always place the dimplers until your dimples are made."According to History By Zim: "The American Medical Association argued that the 'Dimple Maker' would not make dimples or even enlarge original dimples. They also stated that prolonged use of the devise may actually cause cancer."

Louisville Courier-Journal - June 19, 1937

Battle Creek Enquirer - June 19, 1937

Detroit Free Press - Aug 9, 1936

Medford Mail Tribune - Nov 22, 1936

Newsweek - June 19, 1937

1947: Erma Schnitter models the dimple maker

Update: I was curious to know when exactly the American Medical Association denounced the Dimple Maker, since the History by Zim blog didn't mention a date. I tracked it down to 1947, when the AMA put together a collection of quack medical products that it displayed on a nationwide tour of museums.

The Philadelphia Inquirer - Jan 11, 1948

Posted By: Alex - Sun Apr 23, 2017 -

Comments (1)

Category: Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Inventions, 1930s

The Knife-Fork

Edward Towlen of Detroit invented the "knife-fork" around 1917, but he only got around to selling it as a product in 1945. It looks like you can still buy one (or something like it), such as here for $17.99. Although science has moved on. There are now rivals, such as the Knork (see video below).

Wilkes-Barre Times Leader - Dec 15, 1945

Posted By: Alex - Wed Apr 19, 2017 -

Comments (3)

Category: Inventions

“Iron Mask” Wristwatch

I can't find any evidence for the widespread distribution of this watch outside this advertisement. Evidently, it did not catch on. Even Ebay does not seem to feature any as collectibles.

Of course, offering a watch that cost $17.50 (2017 equivalent: $307.40) during the Depression might have had something to do with their failure.

Original advertisement here. (Scroll down.)

Posted By: Paul - Sun Apr 02, 2017 -

Comments (3)

Category: Inventions, 1930s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |