Languages

You Know Scholarship

From Sleeping Dogs Don't Lay: Practical Advice For The Grammatically Challenged by Richard Lederer and Richard DowisThe first year’s winner was thirteen-year-old Dalton Hartman, who submitted a tape with forty-one you knows in four minutes, thirty-eight seconds. The next year, a fifth grader named Jason Rich took the prize. His tape, a twelve-minute interview with a basketball coach, had sixty-four you knows...

Colonel Oldfield has made arrangement in his estate for continuation of the contest.

Oldfield died in 2003. I can't find any evidence that the scholarship did continue after his death. This LA Times article has more info about his somewhat eccentric philanthropy.

Des Moines Register - Feb 16, 1997

Posted By: Alex - Sat Nov 10, 2018 -

Comments (3)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Languages

Prisencolinensinainciusol

From npr.org:"Prisencolinensinainciusol" is so nonsensical that Celentano didn't even write down the lyrics, but instead improvised them over a looped beat.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Aug 11, 2018 -

Comments (6)

Category: Languages, Music, 1970s

Magma’s Invented Language

Vander invented a constructed language, Kobaïan, in which most lyrics are sung. In a 1977 interview with Vander and long-time Magma vocalist Klaus Blasquiz, Blasquiz said that Kobaïan is a "phonetic language made by elements of the Slavonic and Germanic languages to be able to express some things musically. The language has of course a content, but not word by word."[1] Vander himself has said that, "When I wrote, the sounds [of Kobaïan] came naturally with it—I didn’t intellectualise the process by saying 'Ok, now I’m going to write some words in a particular language', it was really sounds that were coming at the same time as the music."[2] Later albums tell different stories set in more ancient times; however, the Kobaïan language remains an integral part of the music.

Their Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Feb 27, 2018 -

Comments (1)

Category: Languages, Music, 1970s, Europe, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

Small Addendum to the Case of Cardinal Sin

More at Wikipedia.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Feb 15, 2018 -

Comments (1)

Category: Languages, Puns and Other Wordplay, Alex

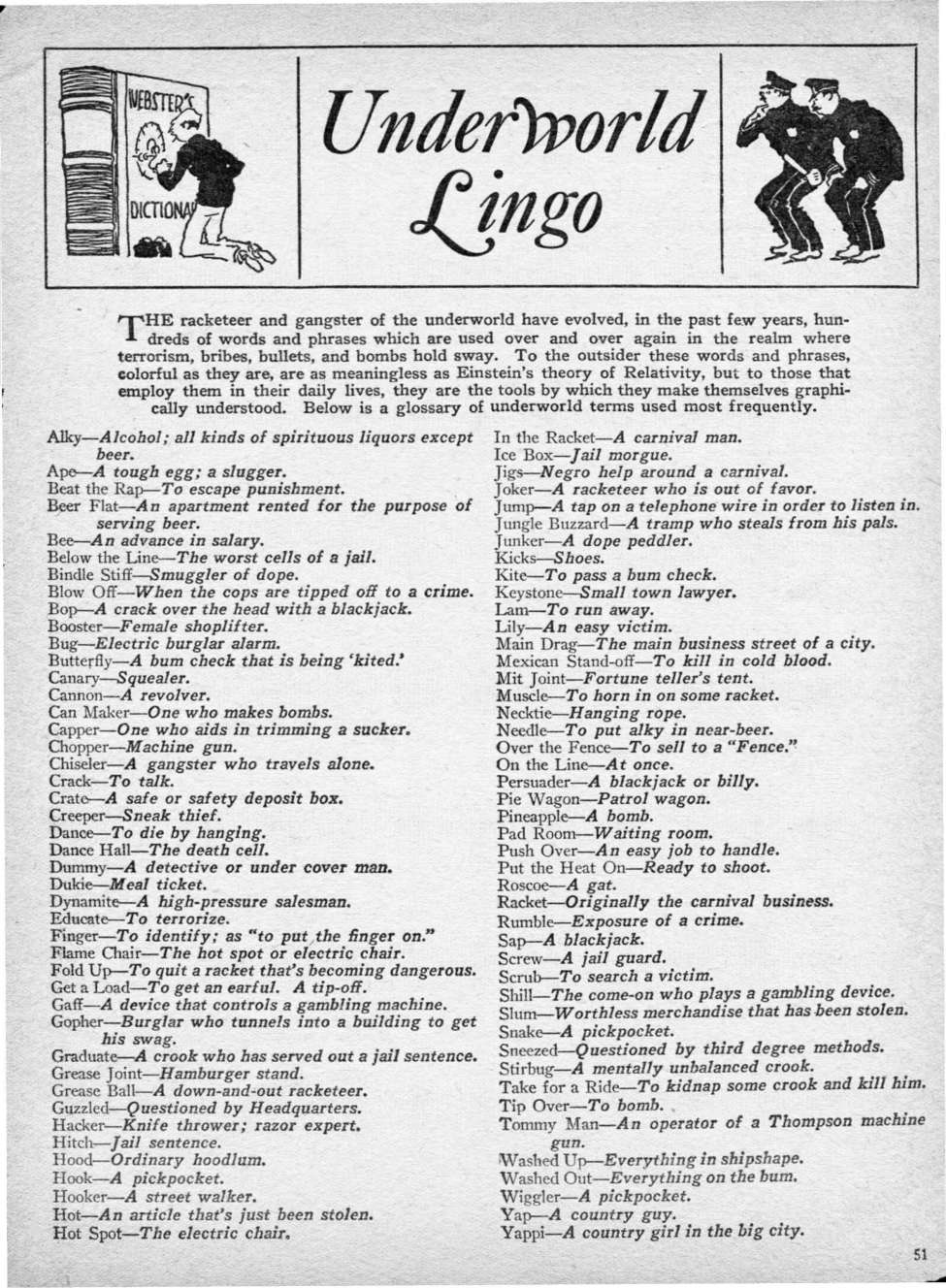

Underworld Lingo

Source: page 51 of this magazine.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jun 12, 2017 -

Comments (6)

Category: Crime, Languages, 1930s

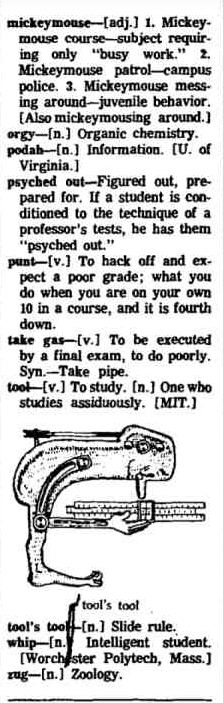

New American Dictionary of Collegese: 1963

Here is another one of those attempts by journalist "squares" to understand the lingo of youths.

Many more entries at the link.

Posted By: Paul - Wed May 31, 2017 -

Comments (5)

Category: Languages, Slang, Teenagers, 1960s

Horn OK Please

Atlas Obscura does a great job explaining the wacky phrase from India, "Horn OK Please." But they do not place the video of the song that uses the same title upfront enough for my tastes!

Posted By: Paul - Tue May 23, 2017 -

Comments (1)

Category: Languages, Slang, Motor Vehicles, India

Quoz!

Quoz was the "whatever" of the 19th century.From Charles Mackay's Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841):

But, like all other earthly things, Quoz had its season, and passed away as suddenly as it arose, never again to be the pet and the idol of the populace.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Apr 15, 2017 -

Comments (1)

Category: Languages, Slang, Nineteenth Century

The Backward Index

Between the 1930s and 1970s, employees at Merriam-Webster created a massive "backward index." It was a card catalog, containing all the words in its dictionary typed backwards. It eventually included around 315,000 index cards.The reason for creating this thing was to allow the company to find words with similar endings. Such as all words ending in 'ological'. It also helped them create a rhyming dictionary.

Computers made the backward index obsolete, but it still sits in the basement of the company's headquarters.

More info: Merriam-Webster

Posted By: Alex - Tue Apr 04, 2017 -

Comments (5)

Category: Languages, Collectors

Andor vs. And/Or

February 1953: The Georgia House of Representatives voted to make "andor" a legal word and directed that it should henceforth be used in place of the phrase "and/or." The House defined "andor" to mean, "either, or, both, and, and or or, and and or."However, the Georgia Senate voted against the bill.

More info: NY Times (Feb 21, 1953)

Minneapolis Star Tribune - Feb 28, 1953

The East Liverpool (Ohio) Evening Review - Feb 26, 1953

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jan 18, 2017 -

Comments (5)

Category: Languages, Law

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |