Law

Isaac Parker, the Hanging Judge

His Wikipedia page tells us:Parker became known as the "Hanging Judge" of the American Old West, because he sentenced numerous convicts to death.[1] In 21 years on the federal bench, Judge Parker tried 13,490 cases. In more than 8,500 of these cases, the defendant either pleaded guilty or was convicted at trial.[2] Parker sentenced 160 people to death; 79 were executed.

Read a memoir that appeared two years after his death at this link.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Sep 17, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Death, History, Wild West and US Frontier, Law, Books, Nineteenth Century

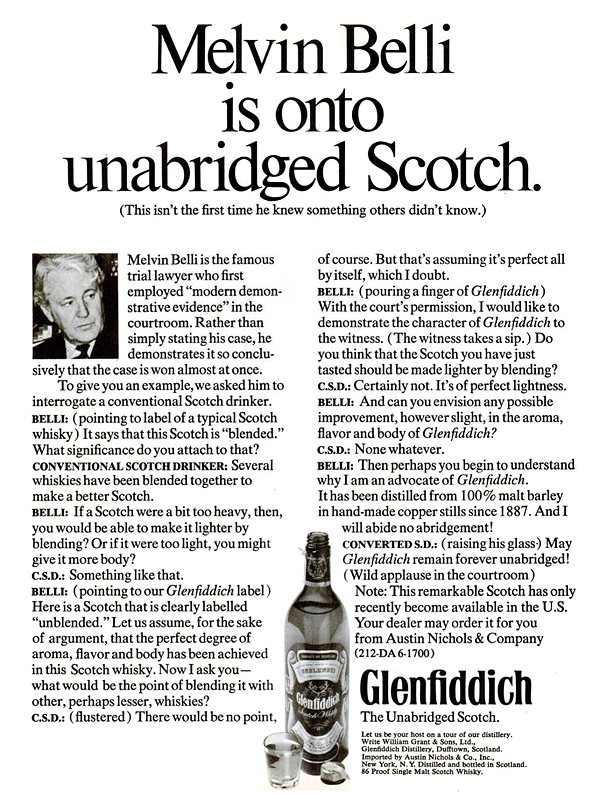

Melvin Belli Drinks Glenfiddich

The ad below, in which trial lawyer Melvin Belli endorsed Glenfiddich scotch, ran in the New York Times and New York Magazine in early 1970. Taken at face value, it doesn't seem like a particularly noteworthy ad. However, it occupies a curious place in legal history.Before the 1970s, it was illegal for lawyers to advertise their services. So when Belli appeared in this ad, the California State Bar decided he had run afoul of this law — even though he hadn't directly advertised his services. It suspended his license for a year. The California Supreme Court later lowered this to a 30-day suspension — but it didn't dismiss the punishment entirely.

Some high-placed judges felt sympathetic to Belli, which added fuel to the movement to end the 'no advertising' law for lawyers, and by 1977, the Supreme Court had struck down the ban on advertising, saying that it violated the First Amendment. That's why ads for legal services now appear all over the place. Compared to the ads one sees nowadays, Belli's scotch endorsement really seems like no big deal at all.

More info: Belli v. State Bar, "Remember when lawyers couldn't advertise?"

New York Magazine - Mar 2, 1970

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 16, 2021 -

Comments (5)

Category: Law, Advertising, 1970s

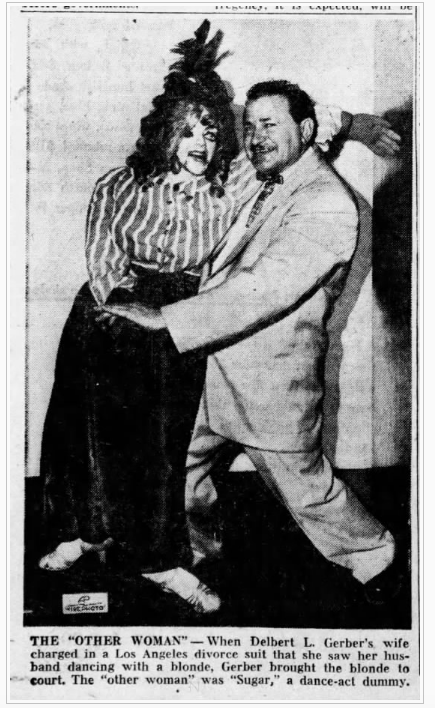

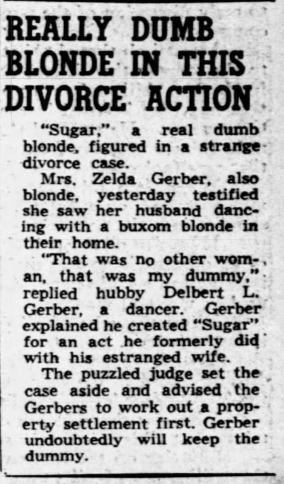

Dummy Divorce

Photo source: The Baltimore Sun Baltimore, Maryland 21 Aug 1953, Fri • Page 4

Text source: Los Angeles Evening Citizen News (Hollywood, California) 21 Aug 1953, Fri Page 11

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jun 19, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Law, Puppets and Automatons, Husbands, Wives, Divorce

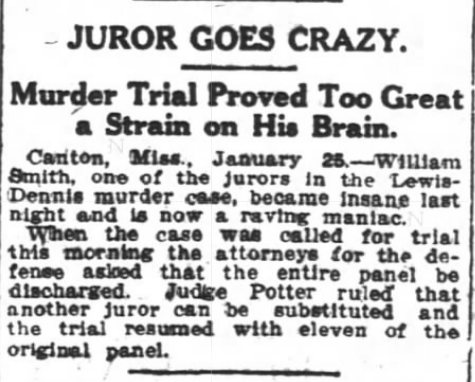

Juror Goes Insane

I would totally cite this precedent when trying to get out of jury duty.

Source: The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia) 26 Jan 1909, Tue Page 9

Posted By: Paul - Sun Mar 21, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Law, 1900s, Mental Health and Insanity

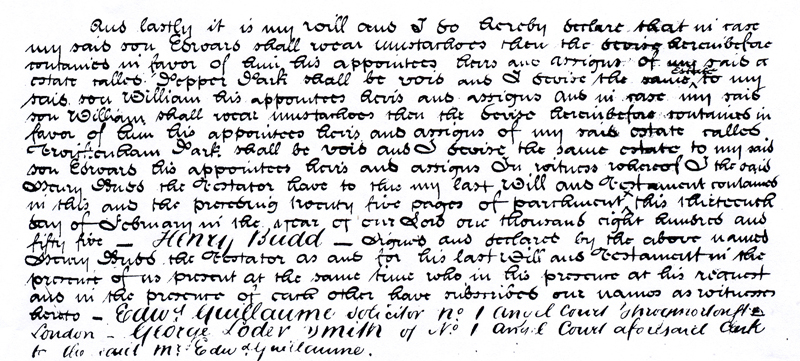

Henry Budd, the Anti-Mustache Millionaire

English eccentric Henry Budd stipulated in his will that his sons would forfeit their inheritance if they ever grew a mustache. Details from twickenhampark.co.uk:The newspapers reported this in some detail at the time, and it was still worthy of news 20 years later in 1882.

Detail from Budd's will in which he forbids his sons from ever growing mustaches

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jan 09, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Law, Nineteenth Century, Hair and Hairstyling

Clothes for Snowmen

Various sources report that when Madame de la Bresse died in 1876, she instructed in her will that all her money be used for buying clothes for snowmen. For instance, Bill Bryson shares this anecdote in his 1990 book The Mother Tongue: English & How it got that Way:Here's a 1955 cartoon about Madame de la Bresse and the snowmen:

The Montana Standard - May 6, 1955

But the earliest source for the story I've been able to find is a 1934 edition of Ripley's Believe it Or Not!. Which makes me wonder if the story is true, because I'm convinced Ripley invented many of his "strange facts". I can't find any French references to Madame de la Bresse.

However, it's possible Madame de la Bresse and her odd bequest were real, and the best argument for this I've been able to find is made by Bob Eckstein in his The History of the Snowman. He doesn't provide any sources to verify the existence of Madame de la Bresse, but he does give some historical context that could explain what might have inspired her to want to clothe snowmen:

The date was December 8, 1870. Snow began to cover Paris. Bored officers threw snowballs, and some of the soldier-artists began to make snow sculptures. Before long, the snowballs became monumental snow statues. One soldier, Alexandre Falguière, channeled his angst of his home city being attacked by creating La Résistance, a colossal snow woman, which was constructed in a mere two to three hours with the help of others.

Although the artist Moulin built a huge snow-bust nearby, it was twenty-nine-year-old Falguière's snow woman that attracted the press to visit the site...

The snow woman was light in the bosom yet clearly blessed with a female face. She had broad shoulders with folded muscular arms and possessed an able-bodied, World Wrestling Federation savoir faire, which suggests Falguière compared the Prussian siege of Paris with the sexual aggression of a relentless female refusing to succumb (La Résistance).

La Résistance by Falguière. Source: wikipedia

So maybe Madame de la Bresse was invented by Ripley. Or maybe she was real and decided to clothe snowmen because she was offended by Falguière's nude snow statue. I'm not sure. Hopefully someone else may be able to shed some light on this mystery!

Posted By: Alex - Sun Dec 13, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Art, Statues and Monuments, Death, Law

The invisible will of Beth Baer

On August 30, 1951, Beth A. Baer sat down to write out a will. She died about two months later. But when her relatives found her will, it turned out to be mostly a blank sheet of paper. Her pen had run out of ink soon after she started writing it, and because she was almost completely blind, she hadn't noticed.However, lawyers Charles Gerard and Clark Sellers were able to figure out what she had written by lighting the paper at an angle and photographing the indentations from the dry pen. Based on this, the court accepted the will as a valid document.

This was bad news for her husband, whom she had decided to leave only $1.

Los Angeles Times - May 13, 1953

Posted By: Alex - Sun Dec 06, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Law, 1950s

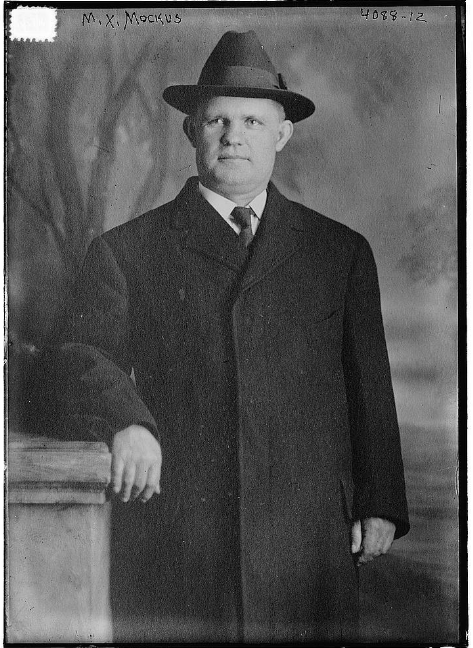

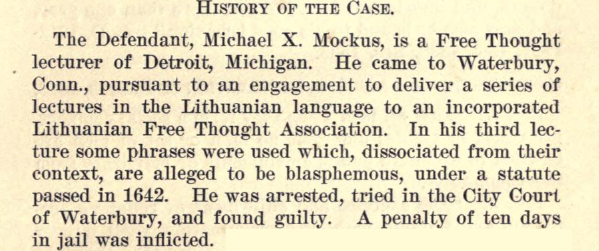

M. X. Mockus, Blasphemer

Read all about it here.

Photo source.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Nov 11, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Law, Religion, 1910s

What rights do goldfish have?

1978: The final act of a British play titled The Last Temptation involved a goldfish bowl, with a live goldfish inside, being thrown across the stage, causing the fish to tumble onto the ground, where it died. Outraged animal lovers sued, prompting a two-year legal battle in which the courts deliberated on whether it was possible to be cruel to goldfish. Or rather, should goldfish enjoy the protections given to other animals such as cats and dogs?The first court ruled that goldfish enjoyed no such protections, but in 1980 the High Court overturned this decision, ruling that it is, indeed, possible to be cruel to goldfish, and that the law should not allow such behavior.

I'm not sure if there's any equivalent American law pertaining to goldfish. But I imagine that if there was then surely boiling lobsters alive would also be illegal.

The Guardian - Nov 3, 1978

Victoria Times Colonist - July 30, 1980

Posted By: Alex - Thu Aug 20, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Law, Fish, 1970s

Constitution of Alabama

Clocking in at 310,296 words, the constitution of Alabama is the longest constitution in the world. By comparison, the U.S. constitution is only 4,543 words (including the signatures).The bloat of the document is a result of the state government deciding that it needed to micromanage the individual counties. So all kinds of local regulations have been included in the constitution. Wikipedia explains:

The Constitutional Convention was called with the intention by Democrats of the state "to establish white supremacy in this State," "within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution." Its provisions essentially disenfranchised most African Americans and thousands of poor whites, who were excluded for decades.

You can read the full document here.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jul 17, 2020 -

Comments (6)

Category: Government, Regulations, Law

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |