Law

Norma Jean Almodovar: Cop to Call Girl

Her Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Mar 10, 2018 -

Comments (0)

Category: Law, Sexuality, Books, 1990s

Lawyer consumption rates of Tyrannosaurus rex

A science question inspired by the scene in Jurassic Park in which the T rex ate the lawyer:How many lawyers would it take to properly feed a captive T rex for an entire year?

The answer: if the T rex is warm-blooded it will need to eat 292 lawyers a year. If cold-blooded, only 73 lawyers.

From The Complete Dinosaur, edited by James Orville Farlow, M. K. Brett-Surman.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jan 23, 2018 -

Comments (3)

Category: Law, Science, Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Creatures

Wizard Amendment

March 1995: During the discussion of a bill in the New Mexico state senate, Sen. Duncan Scott (R) proposed the following amendment:Additionally, a psychologist or psychiatrist shall be required to don a white beard that is not less than 18 inches in length, and shall punctuate crucial elements of his testimony by stabbing the air with a wand. Whenever a psychologist or psychiatrist provides expert testimony regarding the defendant's competency, the bailiff shall contemporaneously dim the courtroom lights and administer two strikes to a Chinese gong.

It passed in the Senate, but didn't make it through the House.

The Marion Star - Dec 28, 1995

Posted By: Alex - Sun Aug 27, 2017 -

Comments (4)

Category: Law, Politics, 1990s

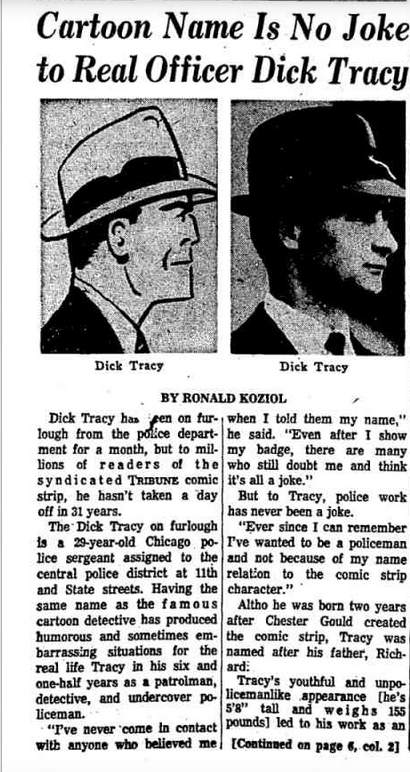

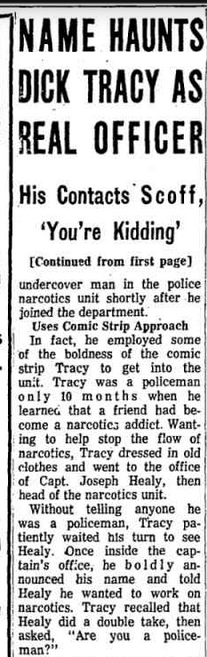

Real-Life Dick Tracy

Original article here.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Apr 10, 2017 -

Comments (0)

Category: Law, Comics, 1960s

Chicago Bar Association Annual Musical Revue

Who knew that Chicago lawyers and judges and other legal folks have been doing a theatrical production for nearly 100 years?

Their home page.

The origin story is told in the 1954 review below.

The videos reveal that none of these folks should leave their day jobs.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Feb 22, 2017 -

Comments (0)

Category: Entertainment, Law, 1920s

Andor vs. And/Or

February 1953: The Georgia House of Representatives voted to make "andor" a legal word and directed that it should henceforth be used in place of the phrase "and/or." The House defined "andor" to mean, "either, or, both, and, and or or, and and or."However, the Georgia Senate voted against the bill.

More info: NY Times (Feb 21, 1953)

Minneapolis Star Tribune - Feb 28, 1953

The East Liverpool (Ohio) Evening Review - Feb 26, 1953

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jan 18, 2017 -

Comments (5)

Category: Languages, Law

Thought she could fly like Batman

Breunig later sued for damages, but Mrs. Veith's insurance company offered an unusual defense. It said she wasn't negligent and therefore not liable because she had been overcome by a mental delusion moments before swerving out of her lane. She hadn't been operating her automobile "with her conscious mind."

The insurance company lost the initial case, but appealed, and eventually the dispute ended up before the Supreme Court of Wisconsin (Breunig v. American Family Insurance Co.). There, the court heard the nature of the mental delusion that had gripped Mrs. Veith:

Actually, Mrs. Veith's car continued west on Highway 19 for about a mile. The road was straight for this distance and then made a gradual turn to the right. At this turn her car left the road in a straight line, negotiated a deep ditch and came to rest in a cornfield. When a traffic officer came to the car to investigate the accident, he found Mrs. Veith sitting behind the wheel looking off into space. He could not get a statement of any kind from her.

The court ultimately agreed with the insurance company that a sudden mental incapacity might excuse a person from the normal standard of negligence. It noted that a Canadian court had once reached a similar conclusion: "There, the court found no negligence when a truck driver was overcome by a sudden insane delusion that his truck was being operated by remote control of his employer and as a result he was in fact helpless to avert a collision."

But the Wisconsin Supreme Court then ruled that this excuse didn't apply in Veith's case because she had had similar episodes before. Therefore, she should have reasonably concluded that she wasn't fit to drive.

This case has become an important precedent in tort law, establishing the principle that you can't use sudden mental illness as an excuse if you have forewarning of your susceptibility to the condition.

The case is such a classic that in an issue of the Georgia Law Review (Summer 2005) it was even described in verse:

| A bright white light on the car ahead, Entranced Erma Veith, so she later said. Pursuing that light, a miracle did unfold: Of Erma's steering wheel, God took control. Under the influence of celestial propulsion, Erma now operated by divine compulsion. She met a truck, and responded in scorn: She hit the gas, so she'd become airborne. Why, Erma, would you seek elevation? "Batman!" she replied, "my inspiration!" Moreover, at trial, other evidence of panic: She had previously invoked the Duo Dynamic. Once to her daughter, she had commented: "Batman is good; your father is demented." The law held sympathy for Erma's plight: After all, mankind has long yearned for flight. Soaring above, slipping gravity's attraction, Many have aspired to that satisfaction. Still, the law cautioned, the limits were great: "Was Erma forewarned of her delusional state?" On this issue, the evidence appeared strong: "She had known of her condition all along." She experienced a vision, at a shrine in a park: When the end came, she would be in the Ark. Indeed, she would assist, in sorting them out: Those to be saved, and those not devout. Knowing all this, said the court in conclusion, She might well expect, she'd suffer delusion. In her condition, a state most bizarre, Erma was negligent, to drive a car. And to Erma, a lesson of universal appeal: "Nothing can emulate the Batmobile!" |

Posted By: Alex - Thu Sep 15, 2016 -

Comments (5)

Category: Law, Lawsuits, 1960s

Joey Reynolds and the Beatles

An ancient manufactured pop-music feud.

The Joey Reynolds story here.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Aug 08, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Law, Music, Rivalries, Feuds and Grudges, 1960s

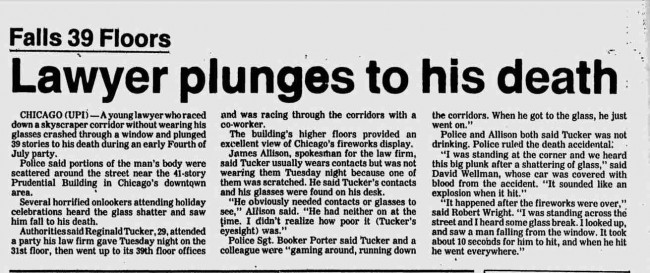

Death by Myopia

Click to embiggen.

Original story here.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Aug 07, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Death, Law, 1980s, Eyes and Vision

The Yellowstone Zone of Death

Yellowstone National Park contains a 50-square mile "zone of death" where, legal scholars suggest, a person could commit murder without fear of prosecution. This zone is the part of the park that extends into Idaho.

The reason for this free-pass-for-murder lies with the Sixth Amendment which guarantees a defendant the right to a trial by a jury "of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed." The zone is in the State of Idaho, but because of the unique legal status of Yellowstone, it's in the judicial District of Wyoming. Therefore, to prosecute anyone a court would need to form a jury of people who live simultaneously in the State of Idaho and the District of Wyoming, and no one fits that bill because no one lives in the Idaho part of Yellowstone. Without being able to create a jury, a trial couldn't proceed.

A similar zone exists in the part of Yellowstone that extends into Montana. However, a few people live there, so a jury could, in theory, be formed from its residents.

This legal loophole was first pointed out in 2005 by Brian Kalt, a professor at Michigan State Law School, in an article published in the Georgetown Law Journal. Kalt urged Congress to pass legislation to fix the loophole before someone tested the loophole by committing murder in the death zone. The simplest fix, he proposed, would be to change the district lines so that the part of Yellowstone in Idaho would be included in the District of Idaho.

To date, Congress has not done anything to fix the problem. Part of the reason for this is political inertia. But there's also resistance to changing the District lines because this would place part of Yellowstone under the jurisdiction of the more liberal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which, it's feared, environmentalists could use to their advantage. So the "zone of death" remains.

The idea of a legal "zone of death" has naturally appealed to the imaginations of artists. The zone was featured in a best-selling mystery novel, Free Fire, by CJ Box. And in 2016 it became the subject of a film, Population Zero (trailer below).

More info: npr.org, bbc news, vox.com.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jul 24, 2016 -

Comments (8)

Category: Crime, Geography and Maps, Law

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |