Literature

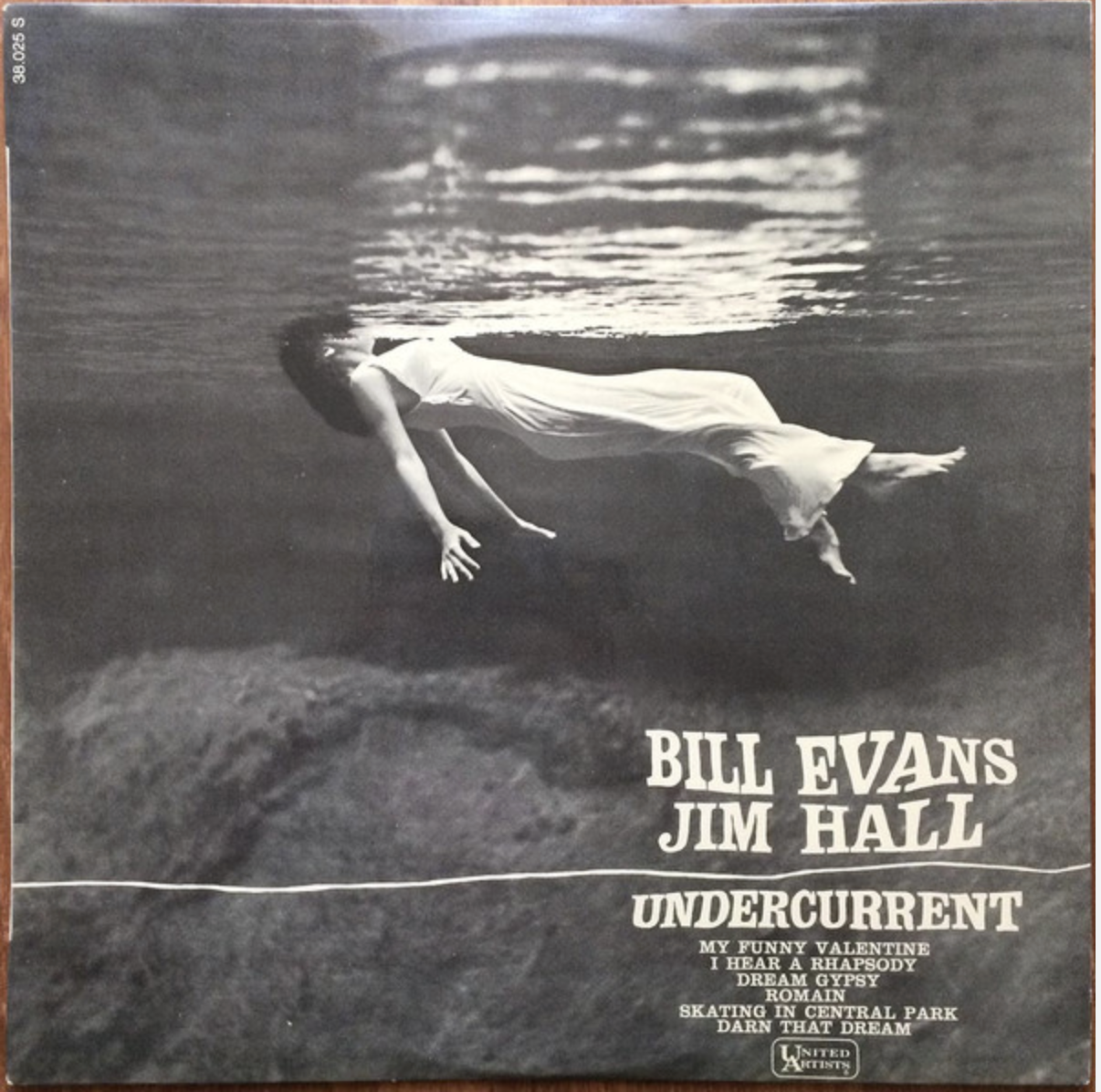

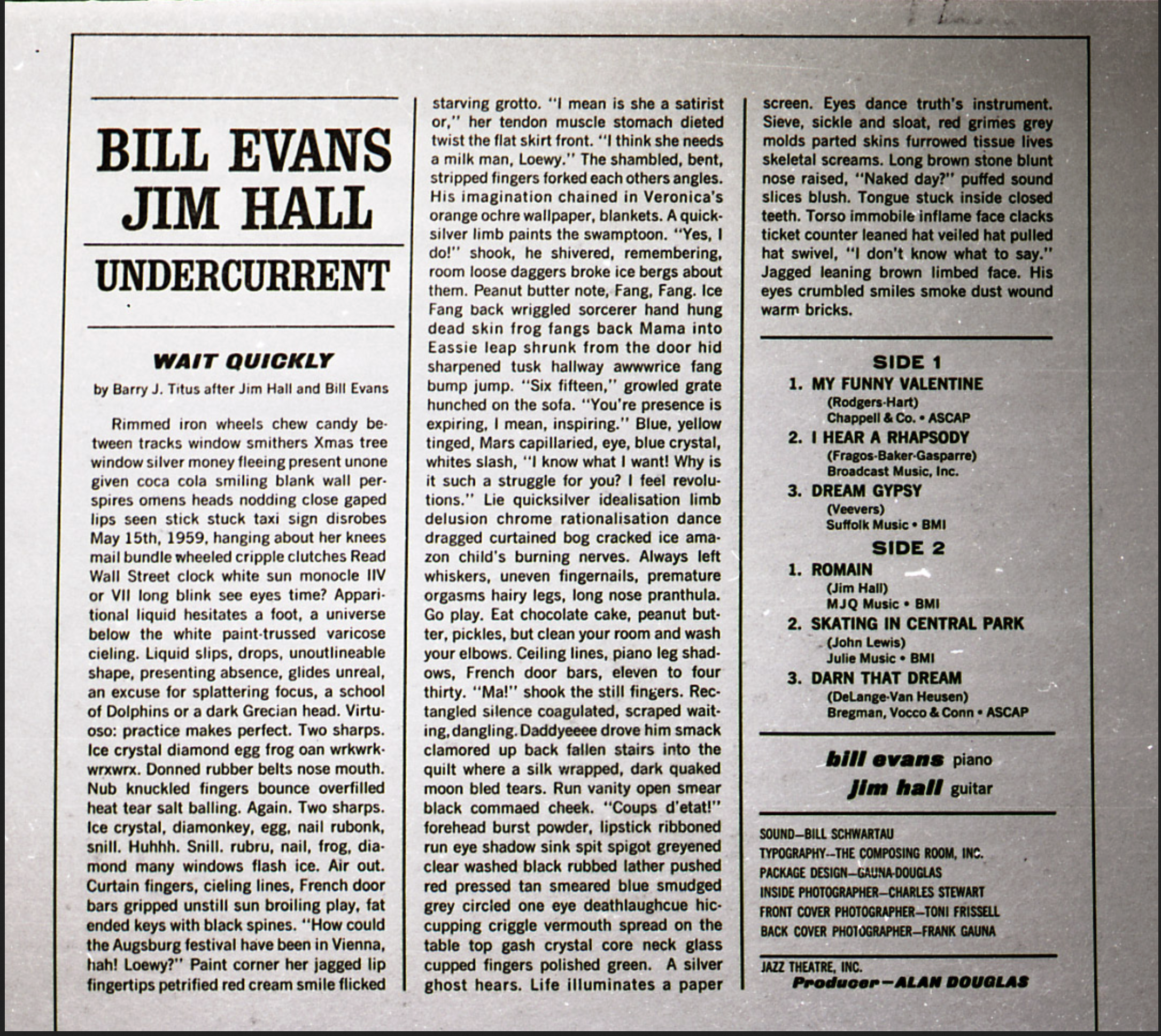

Most Inscrutable Liner Notes Ever

The Wikipedia page for the album.

I have taken the liberty of breaking the text into random paragraphs, to ease your perusal.

Who was the author, Barry Titus? We find record of him under his wife's Wikipedia page.

WAIT QUICKLY by Barry J. Titus after Jim Hall and Bill Evans

Rimmed iron wheels chew candy between tracks window smithers Xmas tree window silver money fleeing present unone given coca cola smiling blank wall perspires omens heads nodding close gaped lips seen stick stuck taxi sign disrobes May 15th, 1959. hanging about her knees mail bundle wheeled cripple clutches Read Wall Street clock white sun monocle IIV or VII long blink see eyes time? Apparitional liquid hesitates a foot, a universe below the white paint-trussed varicose cieling. Liquid slips, drops, unoutlineable shape, presenting absence, glides unreal, an excuse for splattering focus, a school of Dolphins or a dark Grecian head.

Virtuoso: practice makes perfect. Two sharps. Ice crystal diamond egg frog oan wrkwrk-wrxwrx. Donned rubber belts nose mouth. Nub knuckled fingers bounce overfilled heat tear salt balling. Again. Two sharps. Ice crystal, diamonkey, egg, nail rubonk, snill. Huhhh. Snill. rubru, nail, frog, diamond many windows flash ice. Air out. Curtain fingers, cieling lines, French door bars gripped unstill sun broiling play, fat ended keys with black spines.

"How could the Augsburg festival have been in Vienna, hah! Loewy?" Paint corner her jagged lip fingertips petrified red cream smile flicked starving grotto. "I mean is she a satirist or," her tendon muscle stomach dieted twist the flat skirt front. "I think she needs a milk man, Loewy." The shambled, bent, stripped fingers forked each others angles. His imagination chained in Veronica's orange ochre wallpaper, blankets. A quicksilver limb paints the swamptoon. "Yes, I do!" shook, he shivered, remembering, room loose daggers broke ice bergs about them. Peanut butter note, Fang, Fang. Ice Fang back wriggled sorcerer hand hung dead skin frog fangs back Mama into Eassie leap shrunk from the door hid sharpened tusk hallway awwwrice fang bump jump.

"Six fifteen," growled grate hunched on the sofa. "You're presence is expiring, I mean, inspiring." Blue, yellow tinged, Mars capillaried, eye, blue crystal, whites slash, "I know what I want! Why is it such a struggle for you? I feel revolutions." Lie quicksilver idealisation limb delusion chrome rationalisation dance dragged curtained bog cracked ice amazon child's burning nerves. Always left whiskers, uneven fingernails, premature orgasms hairy legs, long nose pranthula.

Go play. Eat chocolate cake, peanut butter, pickles, but clean your room and wash your elbows. Ceiling lines, piano leg shadows, French door bars, eleven to four thirty. "Ma!" shook the still fingers. Rectangled silence coagulated, scraped waiting, dangling. Daddyeeee drove him smack clamored up back fallen stairs into the quilt where a silk wrapped, dark quaked moon bled tears. Run vanity open smear black commaed cheek. "Coups d'etat!" forehead burst powder, lipstick ribboned run eye shadow sink spit spigot greyened clear washed black rubbed lather pushed red pressed tan smeared blue smudged grey circled one eye deathlaughcue hiccupping criggle vermouth spread on the table top gash crystal core neck glass cupped fingers polished green.

A silver ghost hears. Life illuminates a paper screen. Eyes dance truth's instrument. Sieve, sickle and sloat, red grimes grey molds parted skins furrowed tissue lives skeletal screams. Long brown stone blunt nose raised, "Naked day?" puffed sound slices blush. Tongue stuck inside closed teeth. Torso immobile inflame face clacks ticket counter leaned hat veiled hat pulled hat swivel, "I don't know what to say." Jagged leaning brown limbed face. His eyes crumbled smiles smoke dust wound warm bricks.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jul 08, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Literature, Vinyl Albums and Other Media Recordings, Surrealism, 1960s

FINNEGANS WAKE on Audio

Ease yourself into this famously baffling masterpiece by listening to Joyce himself proclaim a passage. Then queue up the whole book on your car's sound system for a relaxing commute!

Posted By: Paul - Thu Feb 23, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Literature, Unexplained Historical Enigmas, 1920s, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

Shakespeare’s Greatest Hits

The Bard's words as you have never dared to imagine them before.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jan 05, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Literature, Music, Vinyl Albums and Other Media Recordings, 1960s

foew&ombwhnw

foew&ombwhnw, by Dick Higgins, was published in 1969 by Something Else Press. The title was an acronym for "freaked-out electronic wizards & other marvellous bartenders who have no wings."The design of the book was unusual. It was made to look like a prayer book, with black cover and thin pages. Inside, the text was divided into four columns. To read the book in order you had to first read all the left-hand columns, then all the second-to-left columns, etc.

The book itself was a collection of essays, plays, and poems. Or, as Higgins described it, "a grammar of the mind and a phenomenology of love and a science of the arts as seen by a stalker of the wild mushroom."

Copies of it generally go for over $100, for anyone interested in adding it to their collection of weird books.

More info: DickHiggins.org

source: printedmatter.org

Posted By: Alex - Sat Dec 10, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Literature, Books, 1960s

Moby Dick, from the whale’s perspective

Artist Wu Tsang's six-hour looping film Of Whales, displayed recently at the 59th Venice Biennale, reimagines the story of Moby Dick, from the whale's perspective. Details from artnet.com:"The work is about reflection in both senses, as well as capturing the whale come out of the water and dive back into it," the artist said, looking at the looping underwater scenes in which the whale remains unseen but is hinted at in fluctuating camera movements. Images of jellyfish float through the water and spiral beams of light reflect across forceful waves.

It doesn't sound like Ahab and crew ever make an appearance, which seems to me like a bit of a lost opportunity. It could have been six hours of jellyfish and waves, followed by five minutes of crazed sailors.

Posted By: Alex - Thu May 05, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Literature, Movies

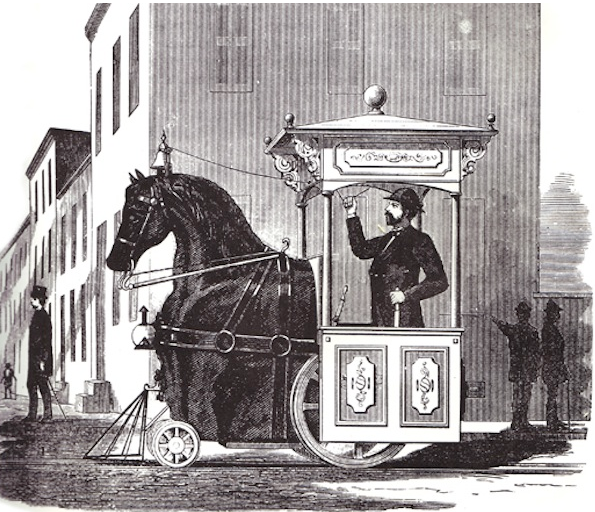

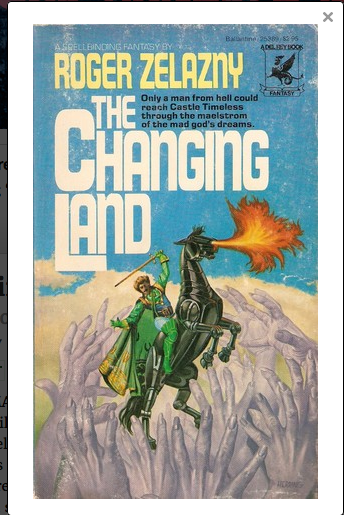

A History of Mechanical Horses

Read the piece here.

There should be a separate article on mechanical horses in literature. My favorite one occurs in these two novels by Roger Zelazny.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Nov 30, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Inventions, Literature, Fantasy, AI, Robots and Other Automatons, Nineteenth Century, Twentieth Century

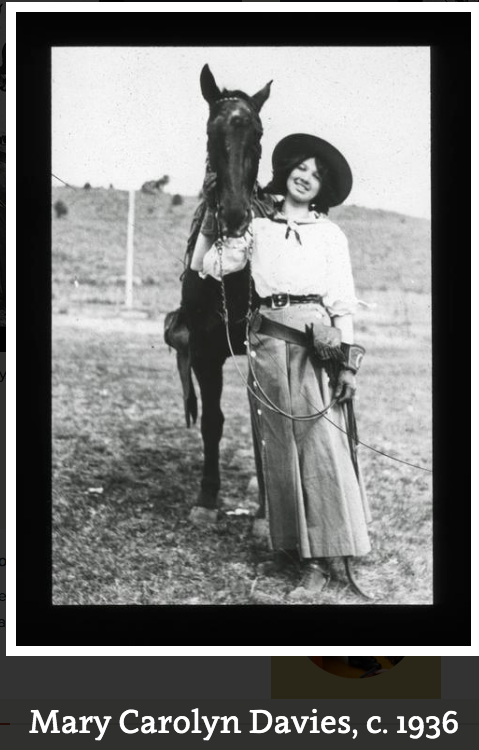

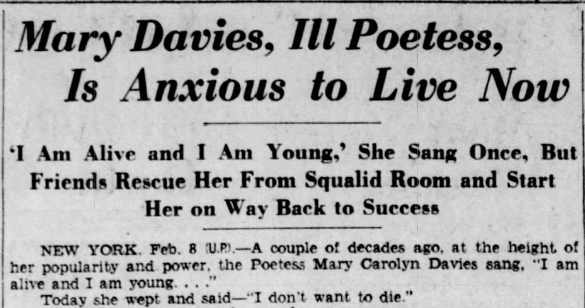

The Odd Downfall of Mary Carolyn Davies

From pulp writer and poet to Skid Row: writing has never been an easy career.

Read the whole arc of her life here.

Read some of her fiction at the Internet Archive.

Newspaper clip from The News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware) 08 Feb 1940, Thu Page 20

Posted By: Paul - Sun Aug 29, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Eccentrics, Literature, Money, Twentieth Century

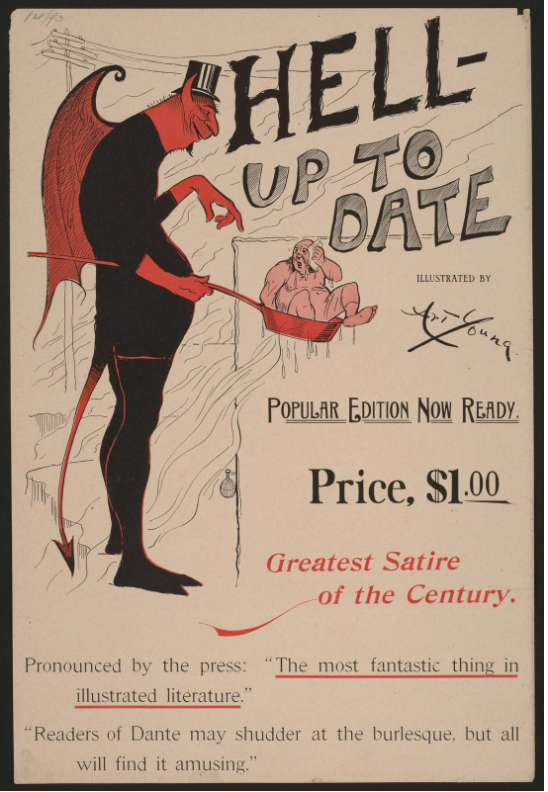

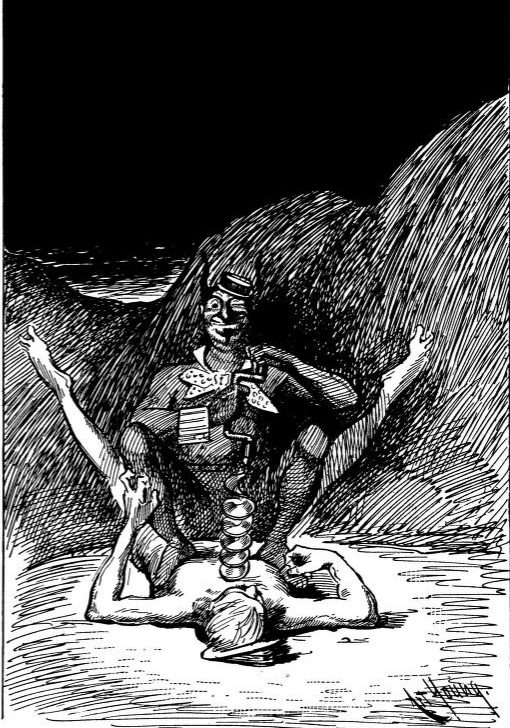

Hell Up To Date

A modern (1894) version of THE INFERNO. Many more weird illustrations at the link, where you may read the whole thing.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Aug 22, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Fate, Predetermination and Inevitability, Literature, Religion, Parody, Satire, Nineteenth Century

The Error in The Ambassadors

The first American edition of Henry James's novel The Ambassadors was published in 1903. But it took 47 years before anyone noticed that there seemed to be a glaring error in it, and the person who noticed was a Stanford undergrad, Robert E. Young. As told by Frances Wilson in the Times Literary Supplement:this reversal of chapters was missed by James, not once but twice. He missed it when he checked the proofs of the novel set by Harper and he missed it again in 1908, during his scrupulous revision of The Ambassadors for Scribner’s New York Edition of his work.

The chapters had actually been printed in the correct order in a British edition, published before the American one. But every subsequent American (and British) edition had used the incorrect order, until Young pointed out the mistake.

Young blamed James's writing style for the error. He concluded his 1950 article in the journal American Literature (in which he exposed the error) with this paragraph:

Naturally, this charge riled James's fans, some of whom sought to defend him. Most notably, in 1992 scholar Jerome McGann argued that James might have intended for the chapters to be in that order. From Wikipedia:

It doesn't seem that many people buy McGann's argument, so the consensus remains that the chapters were out of order and James never noticed.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Mar 22, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Literature, Goofs and Screw-ups

Avakoum Zahov, the Soviet James Bond

Avakoum Zahov was a fictional secret agent who featured in the novels of the Bulgarian writer Andrei Gulyashki. Zahov made his first appearance in the 1959 novel The Zakhov Mission. He returned in the 1966 novel Avakoum Zahov versus 07 — in which he battles and defeats a British agent known as '07'.

image source: pulp curry

There have been persistent rumors that Gulyashki created Zahov at the behest of the KGB in an attempt to produce a Soviet James Bond. Details from an article by Andrew Nette:

It is not clear where McCormick got his information, but others have since picked up the claim and run with it. The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory states that Gulyashki ‘was invited by the KGB to refurbish the image of Soviet espionage which had been tarnished by the success of James Bond’. Likewise, Wesley Britton claims in Beyond Bond: Spies in Fiction and Film that, in 1966, the Bulgarian novelist was hired by the Soviet press to create a communist agent to stand against the British spy ‘because of Russian fears that 007 was in fact an effective propaganda tool for the West’.

"My name is Zahov, Avakoum Zahov" just doesn't have the same ring as "Bond, James Bond".

Posted By: Alex - Sat Feb 06, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Literature, Books, Spies and Intelligence Services, 1960s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |