Medicine

The Family That Walks On All Fours

Full article here.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Mar 03, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Human Marvels, Medicine, Regionalism, Science

The Anomaly That Wouldn’t Go Away

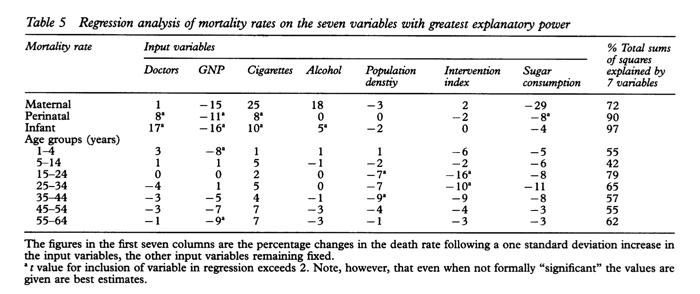

In medical literature, the "anomaly that wouldn't go away" refers to a finding published in 1978 by a group of Welsh doctors (Cochrane, St Leger, and Moore). They had set out to examine the relationship between health services and mortality in the major developed countries, but in doing so they came across a correlation that surprised them — the more doctors there were per capita, the higher was the rate of infant mortality.The correlation wasn't a weak one. In fact, for infant mortality it was the strongest correlation in their study. The number of doctors per capita seemed to have a stronger negative impact on infant mortality than did the level of cigarette or alcohol consumption in the population.

Obviously the researchers found the correlation unsettling since, ideally, more doctors should result in fewer, not more, infants dying.

So why would more doctors correlate with higher infant mortality? The three doctors did their best to figure this out:

As the above passage indicates, they didn't think it was plausible that doctors themselves were somehow responsible for the elevated infant mortality, but nor could they come up with a satisfactory explanation for the correlation. So they called it "the anomaly that wouldn't go away."

I'm not sure if the correlation still holds true. I believe it still did about twenty years ago. Unfortunately much of the relevant literature is locked behind paywalls.

Over the years there have been quite a few attempts to explain the anomaly. I've listed two below. Again, I'm not sure if one has been accepted as THE explanation. So the anomaly may still persist.

It occurred to us that some of the countries richly endowed with physicians may obtain their large supplies by having bigger medical schools, larger classes, and thus less individual instruction of the medical student. The consequence could be a poorer standard of medical practice, the influence of which would be evident in the mortality of the younger age groups where the outcome of disease is most susceptible to the physician's skill.

The explanation proposed here is that, as compared with other regions, the expectation of opportunities in the growing industrial cities initially attracts an over supply of doctors. Once in practice, doctors in new regions enjoy fewer economies of scale, which means that they are more numerous as compared with the mature regions. These same industrialising cities attract rural immigrants whose health habits and supports break down in the context of city life. Thus, the places with the most doctors also have the highest death rates, but the two variables are associated only by common location.

More info (pdf): Cochrane, Leger, & Moore, "Health service 'input' and mortality 'output' in developed countries."

Posted By: Alex - Fri Dec 23, 2022 -

Comments (9)

Category: Babies, Death, Medicine

Breakaway Stethoscope

Joshua Allen Stivers of Puyallup, WA recently received a patent for a "breakaway stethoscope." It works like a normal stethoscope, but breaks apart if someone tries to use it as a garrote to strangle a person:

A quick google search reveals that stethoscopes become weapons disturbingly often. So it's kind of surprising that breakaway ones aren't already standard issue.

Derby Evening Telegraph - Aug 9, 1948

via Jeff Steck

Posted By: Alex - Thu Nov 17, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Crime, Medicine, Patents, Weapons

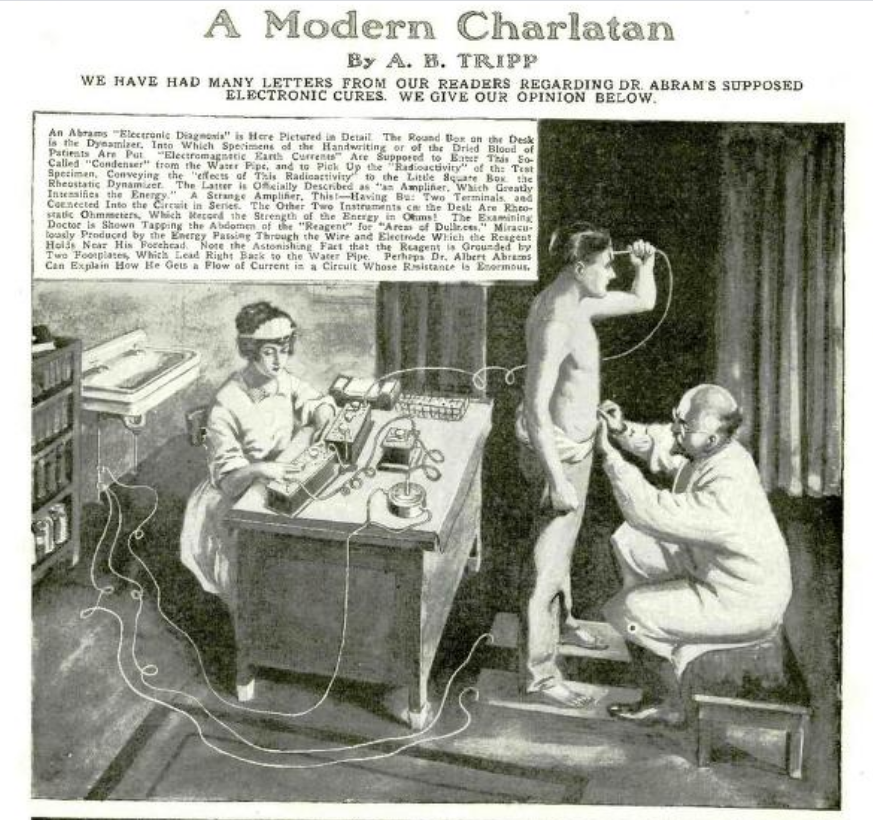

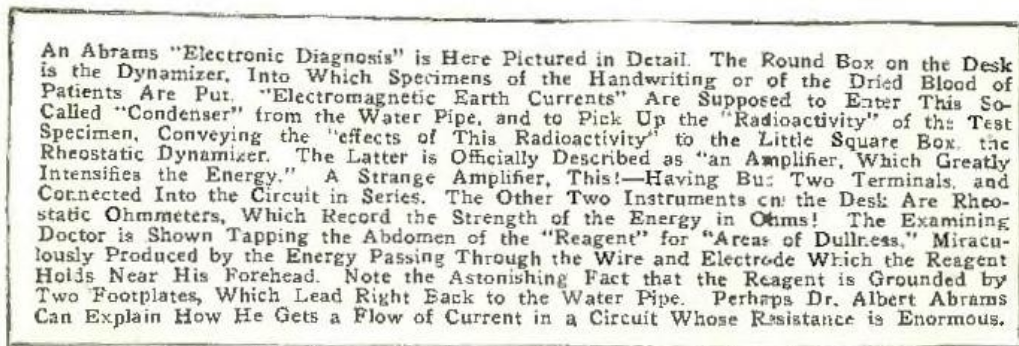

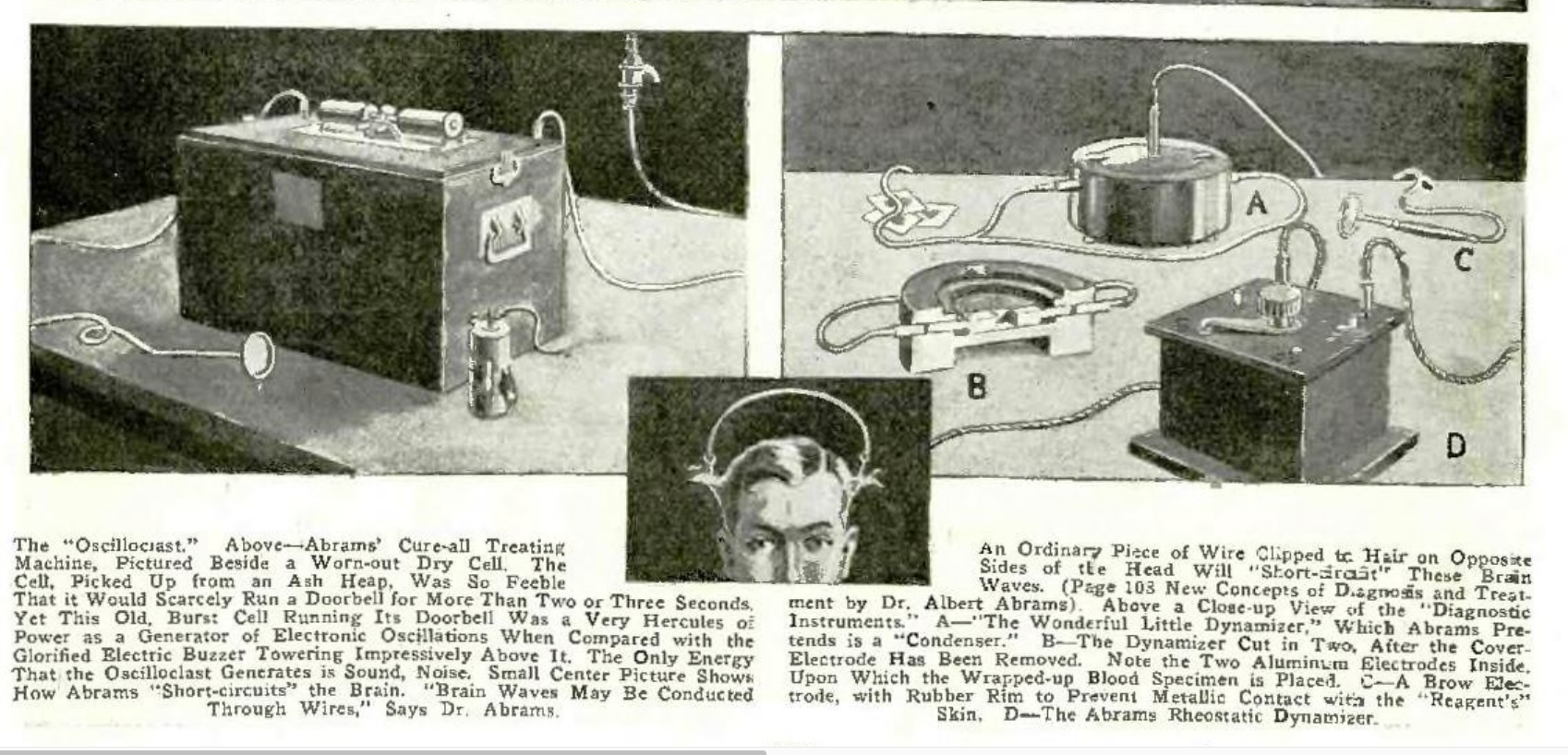

The Cures of Albert Abrams

As his Wikipedia page tells us:Albert Abrams (December 8, 1863 – January 13, 1924) was a controversial American physician, well known during his life for inventing machines, such as the "Oscilloclast" and the "Radioclast", which he falsely claimed could diagnose and cure almost any disease.[1] These claims were challenged from the outset. Towards the end of his life, and again shortly after his death, many of his machines and conclusions were demonstrated to be intentionally deceptive or false.[2]

He actually published a whole periodical devoted to his theories. Read an issue here.

Hugo Gernsback, the father of modern science fiction, was having none of this, running the expose below in a 1923 issue of his magazine SCIENCE AND INVENTION.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Oct 14, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Frauds, Cons and Scams, Hoaxes and Imposters and Imitators, Medicine, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1920s

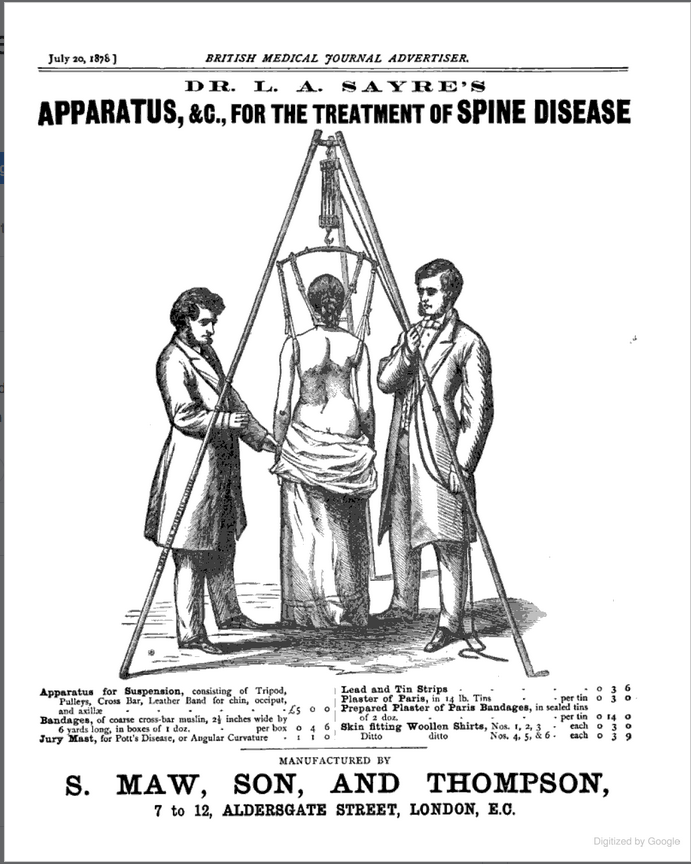

Dr. L. A. Sayre’s Apparatus

Not sure how long the patient was to remain suspended in order to achieve results.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Oct 09, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Inventions, Medicine, Nineteenth Century

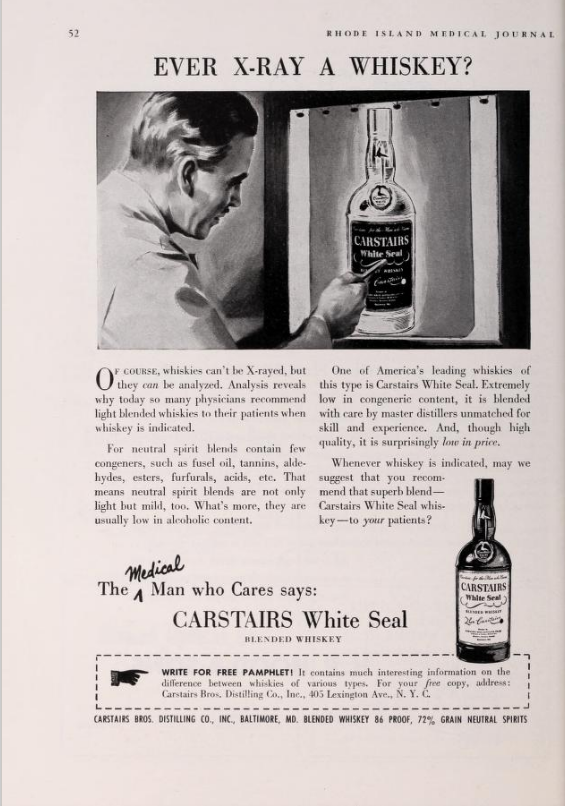

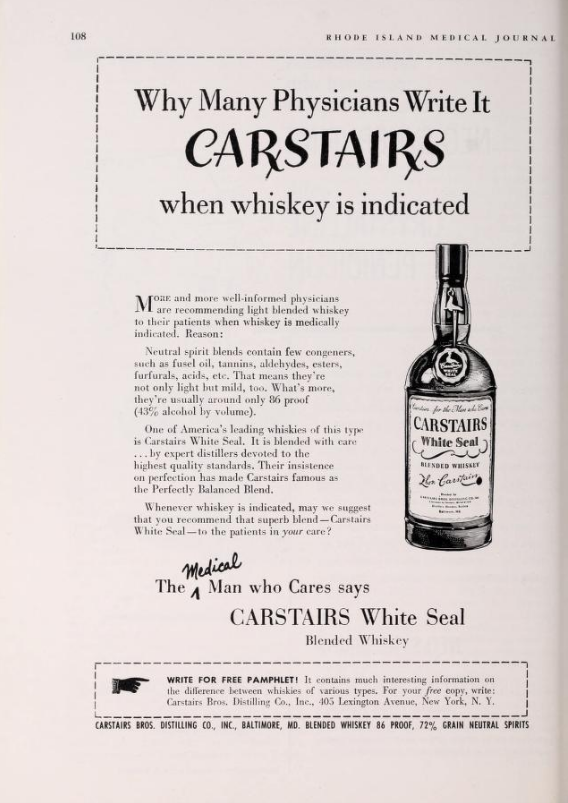

Follies of the Madmen #542

Which booze does your doctor recommend?Source.

Source of second ad.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Sep 27, 2022 -

Comments (7)

Category: Medicine, Advertising, 1950s, Alcohol

Medicine, Mind and Music

Player embedded below the Tracklist. Enjoy!

Posted By: Paul - Sat Aug 06, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Medicine, Music, 1970s, Brain

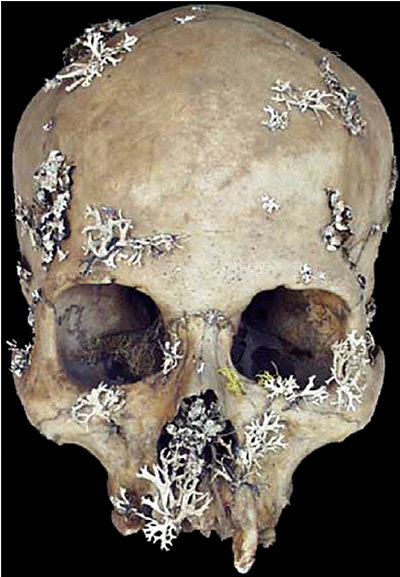

Usnea, or Skull Moss

Source: Howard W. Haggard, Devils, drugs, and doctors (1929).

image source: reddit

More info from Frances Larson, Severed: A History of Heads Lost and Heads Found (2014):

There were reports of people growing moss on stones and then spreading it onto the skulls of criminals, as a way of harvesting the tiny green plants for sale. In practice, apothecaries probably used anything that grew on skulls, and some things that did not grow on skulls, to maintain their supplies.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Apr 29, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Medicine, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, Renaissance Era

Wiggle Room

Must have been a slow news day at the Newport Daily News (Newport, Rhode Island)for 26 Jan 1966, Wed Page 22.

I assume everyone can picture Ann-Margret, Marlo Thomas and Ursula Andress. But for your benefit, here is wiggler Diane Cilento, Mrs. Sean Connery.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Mar 22, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Medicine, Sexuality, Studies, Reports, White Papers, Investigations, 1960s, Women

Beatniks Against Polio

What was the secret ingredient that made the rollout of the polio vaccine go so smoothly? Beatniks! If only we had some around today...Article source: Nashville Banner (Nashville, Tennessee) 16 Aug 1956, Thu Page 13

Posted By: Paul - Wed Nov 10, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Medicine, Bohemians, Beatniks, Hippies and Slackers, 1950s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |