Medicine

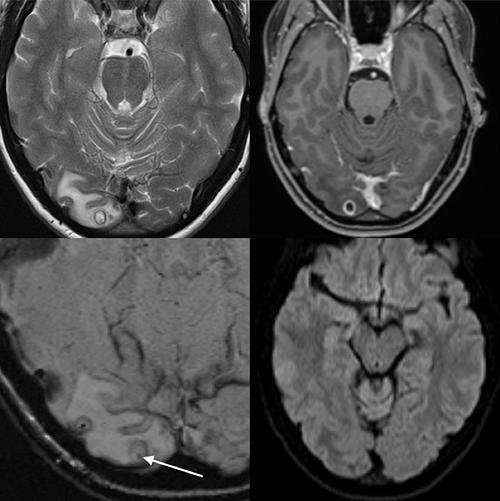

Brain worm

An Australian woman had been suffering from headaches for seven years. Doctors suspected a brain tumor. The good news was that, after operating, they found she was tumor free. The bad news was that she had a cyst full of tapeworm larvae in her brain.More info from cnn.com. Or read the full case report in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Oct 13, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Health, Medicine, Brain

Back Rub

Posted By: Paul - Tue Sep 08, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Body, Hygiene, Baths, Showers and Other Cleansing Methods, Medicine, Music, 1950s

Removing cockroaches from the ear: a comparative study

Back in 1985, doctors at an emergency room in Pittsburgh were presented with a woman who had somehow got cockroaches in both her ears. The doctors immediately decided this presented a rare opportunity to do a comparative study on methods of removing cockroaches from ears. They reported on their results in the New England Journal of Medicine, "Removing Cockroaches from the Auditory Canal: Controlled Trial," 1985, 312(18): 1197.A patient recently presented with a cockroach in both ears. The history was otherwise noncontributory. We recognized immediately that fate had granted us the opportunity for an elegant comparative therapeutic trial. Having visions of a medical breakthrough assuredly worthy of subsequent publication in the Journal, we placed the time-tested mineral oil in one ear canal. The cockroach succumbed after a valiant but futile struggle, but its removal required much dexterity on the part of the house officer. In the opposite ear we sprayed 2 per cent lidocaine solution. The response was immediate; the roach exited the canal at a convulsive rate of speed and attempted to escape across the floor. A fleet-footed intern promptly applied an equally time-tested remedy and killed the creature using the simple crush method.

However humble the method, and despite our small study population, we think we have provided further evidence justifying the use of lidocaine for the treatment of a problem that has bugged mankind throughout recorded history.

K. O'Toole, M.D.

P.M. Paris, M.D.

R.D. Stewart, M.D.

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

R. Martinez, M.D.

Louisiana State University

A subsequent letter to the journal noted a limitation of their report. In many cases, cockroaches get stuck in the ear canal. In which case, they can't just scurry out when sprayed with lidocaine. However, the correspondents offered a method of dealing with this situation. ("Removing cockroaches from the auditory canal: a direct method" NEJM. 1989. 320(5): 322).

As we burst into the room, we could see the young woman writhing from the combined sensations of movement and pain in her ear canal. One of us tok a look, confirming the nurse's diagnosis, while the other filled a 3-cc syringe with 2 percent lidocaine solution. With hurried anticipation we sprayed the drug briskly into the ear canal and quickly jumped back, fully expecting the beast to come hurtling forth at first contact with the noxious substance.

Nothing. "Increase the dosage," we shouted, filling a 10-cc syring. Still nothing. "Get that sucker outa my ear!" the patient screamed. What a brilliant idea! We grabbed a 2-mm metal suction tip and attached it to a wall suction apparatus with a negative pressure of 120 cm of water. Then we gently passed the tip into the ear canal, taking care not to occlude the canal and risk tympanic-membrane barotrauma. Shloop! "Got him!" we exulted. Sure enough, there he was, plastered to the suction tip like a fly to flypaper. After a repeat examination of the canal and a few drops of Cortisporin solution, the patient was on her way.

We recommend suction as a safe and efficacious method for removing insects from the ear canal when other methods fail.

Jonathan Warren, M.D.

Leo C. Rotell, M.D.

State University of New York

Health Science Center

Posted By: Alex - Wed Apr 29, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Insects and Spiders, Medicine, 1980s

Can fear cure cancer?

In 1962, East German researchers conducted a bizarre medical experiment in an attempt to find out if fear could cure cancer. They inoculated some "mice, rabbits, rats, and cocks" with cancer cells. Then they put these animals into a cage which they lowered "into a zoo-like enclosure where 30 ravenous African polecats paced for food. The polecats would leap upon the little cage, shrieking and clawing at their hoped-for prey." This terror experience was repeated every two hours for several days.The result: the cancer cells grew more slowly in the terrorized animals.

Of course, this begs the question, what it is about fear that would fight cancer? Was it the elevated adrenalin levels? Or was there some other biochemical change that caused the effect?

Unfortunately, I can’t find any other details about this unusual experiment except for the brief news report below. I'm assuming there was never a human version of the experiment. Though one never knows, given some of the other stuff that researchers got up to behind the Iron Curtain.

The Paterson News - Nov 7, 1962

Posted By: Alex - Fri Mar 27, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Medicine, Science, Experiments, 1960s

Just Can’t Put My Finger On It

Who knew this was a technique? See a more recent incident after the first story.DOCTOR MAKES A DRAMATIC RESCUE

Karen Dillon

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

Dr. Wendy Marshall was jolted awake at 5 a.m. by an urgent phone message: Doctors at a Joliet hospital were using nothing but their fingers to plug two bullet holes in a man`s heart in a last-ditch effort to save his life.

The doctors at Silver Cross Hospital ''said they had their fingers in the holes and couldn`t stop the bleeding,'' Marshall recounted Thursday.

In an age when sophisticated medical equipment can keep patients alive for months, this most basic technique ultimately saved the life of Tommy Lee

''Tony'' Hairston, of Joliet.

Before the night was over, Marshall, a cardiac surgeon and director of the Loyola University Medical Center`s Trauma Center and the Air Medical Service, would be flown to Joliet and use her own fingers to dike the holes. At the same time, Marshall squeezed the 29-year-old man`s heart to force it to pump when it stopped three times for a total of eight minutes.

Eventually, Hairston was taken by helicopter to Loyola where open heart surgery was performed. Thursday night he was listed in critical condition, but was expected to recover.

The drama began Wednesday night when Hairston, a landscaper shot after an argument with a neighbor over missing property, was taken to Silver Cross Hospital in Joliet.

Silver Cross physicians immediately operated on Hairston, but did not open up the victim`s heart. ''The surgeon found blood in the chest and a couple holes around the heart. At that time, he didn`t open up the heart,''

said Dr. Robert Freeark, chief of surgery at Loyola.

But then after surgery, Hairston started bleeding again. ''This time the surgeon opened Hairston up and and found two holes in his heart . . . and he couldn`t stop the bleeding,'' Freeark said.

The physicians did the only thing they could-stick their fingers into the holes in Hairston`s heart.

Marshall arose, dressed and was taken by helicopter to Silver Cross, accompanied by a paramedic, Kent Adams, and Laurie Dudek, a flight nurse. They arrived 23 minutes after the call.

At Silver Cross, Marshall found a hole in the front of the heart and one in the back. The location of the one in the back was in an area where it couldn`t be repaired without stopping the heart, she said, and Silver Cross didn`t have the equipment for such specialized treatment.

So it meant transporting Hairston to Loyola Medical Center-with Marshall`s fingers in the holes.

Before the night was over, Marshall, as her fingers plugged the holes, squeezed Hairston`s heart to force it to pump when it stopped three times for a total of eight minutes.

Marshall said she used the first two fingers of her right hand to plug the back hole and her right thumb to stop up the front hole. ''When the heart stopped, I kept my fingers in the holes and squeezed my left hand against the right.''

During the flight, Adams, the paramedic, forced Hairston to breathe by squeezing a bag attached to a tube that was shoved down his trachea.

Four intravenous tubes were attached to Hairston, feeding medicine to stimulate his heart beat-one into a large vein near his left collar bone, two to his left arm and one in his right arm.

When the team finally arrived at Loyola, cardiac surgeon Henry Sullivan had been alerted. The patient was placed on a machine that circulated his blood while the heartbeat was halted and the organ repaired, Freeark said.

Adams shook his head in wonder Thursday afternoon. ''It was dramatic,''

he said.

Adams said Marshall was steady as a rock during the flight. ''She was so calm. She just let us know what was happening, and then we did our part.''

Hairston allegedly was shot by Robert Knox, of Joliet, after an argument over some items reported missing from Hairston`s apartment, Joliet police said. Knox was charged with attempted murder, armed violence and unlawful use of a weapon, police said.

By Thursday afternoon, Hairston had awakened a few times, which is considered a positive sign, Marshall said.

Hairston ''is lucky to be alive today,'' she said. ''When the heart stops, most people are basically brain dead within three to four minutes.''

Freeark and another Loyola heart physician, Dr. Bruce Lewis, said that saving Hairston`s life by plugging the holes in his heart was amazing.

''To my knowlege it was totally unprecedented,'' Freeark said. ''Nobody has ever been transferred with a finger better.''

''Very, very amazing, and very rare to see someone survive after that . . . especially with the size of the hole (in the back of the heart),'' Lewis said.

Marshall took the praise in stride. ''Anyone who has got a blood pressure can be saved. So you go for it.''

Source.

Heroic military veterans and police officers put their training to use during the deadly mass shooting at a Las Vegas music concert — even “plugging bullet holes with their fingers,” according to a report.

“You saw a lot of ex-military just jump into gear,” witness Russell Bleck told the “Today” show on NBC. “I saw guys plugging bullet holes with their fingers.”

“While everyone else was crouching, police officers (were) standing up at targets, just trying to direct people, tell them where to go,” he added. “The amount of bravery I saw there, words can’t describe what it was like.”

The practice of plugging gunshot wounds helps to kick in the body’s defense mechanisms that prevent rapid blood loss, according to a Wired report.

Severe wounds, especially on the carotid arteries of the neck, must be quickly plugged with the fingers or packed to temporarily stop the hemorrhaging, according to Gould and Pyle’s Pocket Cyclopedia of Medicine and Surgery.

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Mar 09, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Body, Blood, Death, Guns, Medicine, Superheroes, 1980s, Twenty-first Century

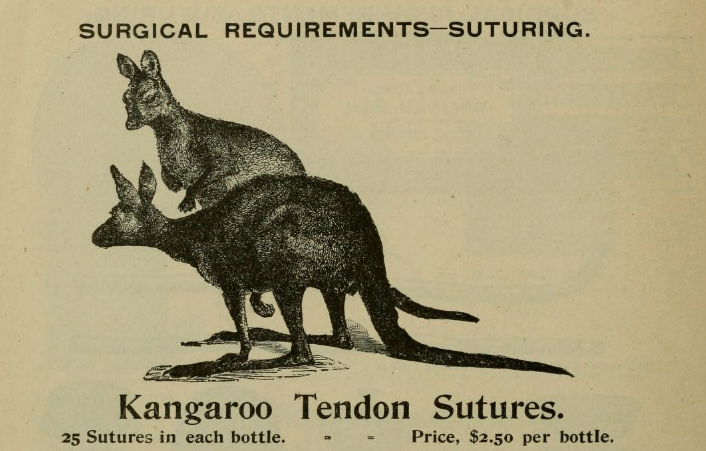

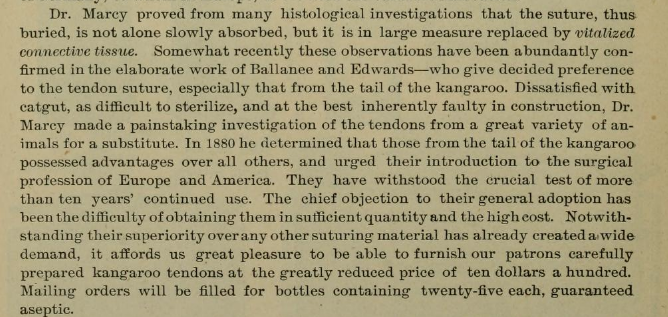

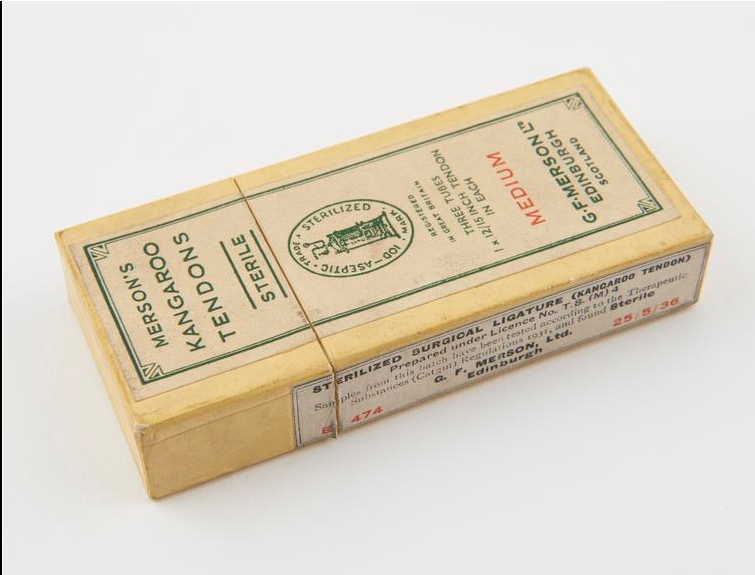

Kangaroo Tendon Sutures

Source of first two images, with further explanation.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Feb 19, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Medicine, Nineteenth Century

Human-Animal Breastfeeding

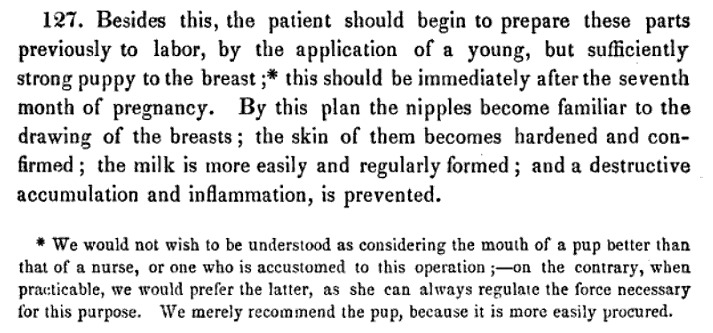

In his 1826 book A Treatise on the Physical and Medical Treatment of Children, the American physician William Potts Dewees offered this advice for pregnant women:

The Wikipedia article Human-animal breastfeeding offers some background info:

English and German physicians between the 16th and 18th centuries recommended using puppies to "draw" the mother's breasts, and in 1799 the German Friedrich Benjamin Osiander reported that in Göttingen women suckled young dogs to dislodge nodules from their breasts. An example of the practice being used for health reasons comes from late 18th century England. When the writer Mary Wollstonecraft was dying of puerperal fever following the birth of her second daughter, the doctor ordered that puppies be applied to her breasts to draw off the milk, possibly with the intention of helping her womb to contract to expel the infected placenta that was slowly poisoning her.

Animals have widely been used to toughen the nipples and maintain the mother's milk supply. In Persia and Turkey puppies were used for this purpose. The same method was practised in the United States in the early 19th century; William Potts Dewees recommended in 1825 that from the eighth month of pregnancy, expectant mothers should regularly use a puppy to harden the nipples, improve breast secretion and prevent inflammation of the breasts. The practice seems to have fallen out of favour by 1847, as Dewees suggested using a nurse or some other skilled person to carry out this task rather than an animal.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jan 18, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Medicine, Nineteenth Century, Pregnancy

Using Coca-Cola to dissolve phytobezoars

Coca-Cola isn’t just for drinking. It also has a medical use: to dissolve gastric phytobezoars (masses of indigestible material in the gastrointestinal system). Doctors administer the Coca-Cola via a tube threaded through the nose down into the intestines. As noted in a 2015 article in the World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, "An administration of Coca-Cola® is believed to be the primary choice for phytobezoar treatment because it is safe, inexpensive, and effective."The same article further explains:

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jun 26, 2019 -

Comments (3)

Category: Medicine, Soda, Pop, Soft Drinks and other Non-Alcoholic Beverages

The Death Test

It's officially known by the acronym CrisTAL (Criteria for Screening and Triaging to Appropriate Alternative Care), but it's more widely known as the Death Test. It's a 29-point checklist to help doctors determine if elderly patients are at risk of dying within the next three months. So, it seems like a more rigorous version of the "Surprise Question" which (as we've posted about before) is another test docs use to predict imminent death.More info: funeralwise.com

The Death Test:

1. Altered level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Score change >2 or AVPU=P or U)

2. Blood pressure (a systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg)

3. Respiratory rate of more then five and less than 30

4. Pulse rate of less than 40 or more than 140

5. Need for oxygen therapy, or known oxygen saturation of less than 90 per cent

6. Hypolglaecemia blood glucose level (less sugar in the blood than normal)

7. Repeat or prolonged seizures

8. Low output of urine (less than 15 mL/h or less than 0.5 mL/kg/h) or a MEW or SEWS score of more than 4

9. Previous history of disease, including:

10. Advanced cancer

11. Kidney disease

12. Heart failure

13. Various types of lung diseases

14. Strokes and vascular dementia

15. Heart attack

16. Moderate to severe liver disease

17. Mental impairment such as dementia or disability from a stroke

18. Length of stay before this RRT call (>5 days predicts 1-year mortality)

19. Repeat hospitalisations in the past year

20. Repeat admission to the intensive care department of the hospital

21. Frailty

22. Unexplained weight loss

23. Self-reported exhaustion

24. Weakness (being unable to grip objects, being unable to handle objects or lift heavy objects of less than or equal to 4.5kg,

25. Slow walking speed (walks 4.5m in more than 7 seconds) or is

26. Inability to do physical exercise or stand

27. Is a nursing home resident or lives in supported accommodation

28. Having urine in their blood (more than 30mg albumin/g creatinine

29. Abnormal ECG (irregular heartbeat, fast heartbeat and any other abnormal rhythm or more than or equal to 5 ectopics/min and changes to Q or ST waves)

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jun 13, 2019 -

Comments (2)

Category: Death, Medicine

The Yips Phenomenon in Golf

The Yips are defined as "a disorder in which golfers complain of an involuntary movement — a twitch, a jerk, a flinch — at the time they putt or even when they chip. This interferes with their ability to perform that activity.” It was the subject of a multidisciplinary study by researchers at the Mayo Clinic, who concluded:The Yips should not be confused with the Yip Yips, which are something completely different:

Posted By: Alex - Wed May 15, 2019 -

Comments (0)

Category: Medicine, Sports, Golf

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |