Medicine

Refrigerated Camels

Instead of using refrigerated trucks to deliver medical supplies to people who live in the deserts of Africa, inventors have built solar-powered refrigerators that can be carried by camels, and so the medicines are delivered via refrigerated camel.Apparently it wasn't that easy to build a camel-carried refrigerator. It had to be lightweight, but also sturdy enough to survive the motion of being on the camel as well as the extreme desert conditions.

More info: ABC News, inhabitat.com

Posted By: Alex - Wed May 31, 2017 -

Comments (4)

Category: Animals, Inventions, Medicine, Transportation, Africa

Collie Nose

Generally, one should not scribble on one's dog with a black felt tip pen, nor tattoo the animal. However...

Posted By: Paul - Mon Apr 03, 2017 -

Comments (1)

Category: Medicine, Dogs, Tattoos

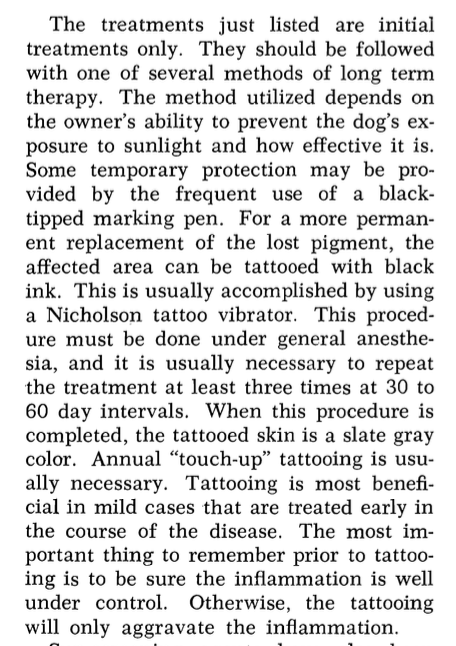

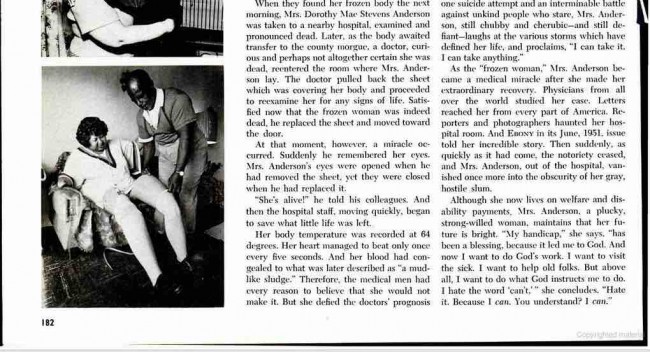

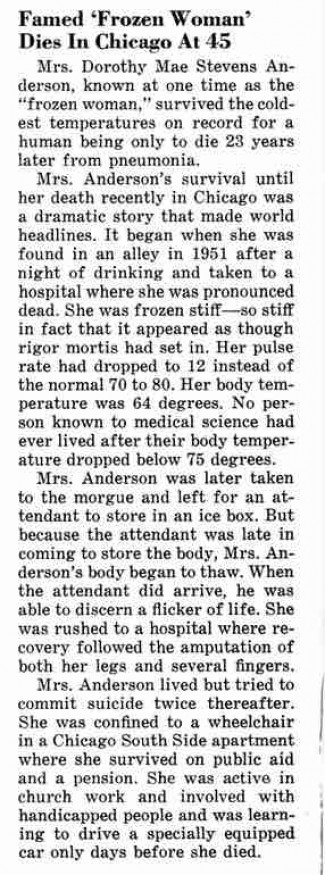

The Frozen Woman

Original article here.

Alas, two years after the coverage above, she was gone.

Original article here.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Nov 17, 2016 -

Comments (6)

Category: Body, Human Marvels, Medicine, Nature, 1950s, Alcohol

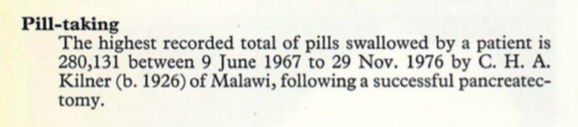

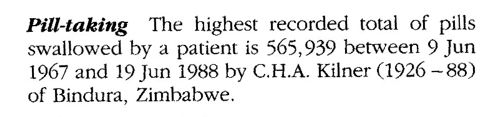

Most Pills Swallowed

One of the world records that Guinness no longer tracks is that for "most pills swallowed." But from the late 1970s to the 1990s it consistently awarded this to one C.H.A. Kilner of Malawi (or perhaps Zimbabwe — accounts differ), who apparently took A LOT of pills following a pancreatectomy (removal of his pancreas) on June 9, 1967.The exact number of pills taken by Kilner progressively increased over time. The 1978 edition of Guinness put it at 280,131 pills. A year later it had reached 311,136. By 1981 it was 359,061. And Kilner finally stopped taking pills on June 19, 1988, having reached a total of 565,939 pills.

Later reports did the math and figured out that this worked out to 73 pills a day, and that "if all the pills he had taken were laid out end to end they would form an unbroken line two miles 186 yards long."

Where exactly was Guinness getting this information from? I have no idea, because they seem to be the only source for it. I can't find any record of this Kilner guy in medical journals.

Guinness Book of Records - 1978 Edition

Detroit Free Press - Dec 4, 1978

Logansport Pharos Tribune - Feb 7, 1982

Guinness Book of Records - 1995 Edition

Posted By: Alex - Sun Nov 06, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Medicine, World Records

Buttered Flip

In an old American medical journal, The Philadelphia Medical Museum (1811 - Vol 1, No.4), Dr. Richard Hazeltine of Berwick, Maine shared a traditional yankee recipe for "buttered flip" cough medicine:

The "buttered flip" was composed of recent urine, obtained from some one of the children, hot water, honey, and a little butter: and it generally removed the complaints for which it was given. Exhibited in this manner, it never puked; but it promoted expectoration and sweat.

image source: gracious rain

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 29, 2016 -

Comments (6)

Category: Medicine, Body Fluids

Treating Tuberculosis with Sunlight

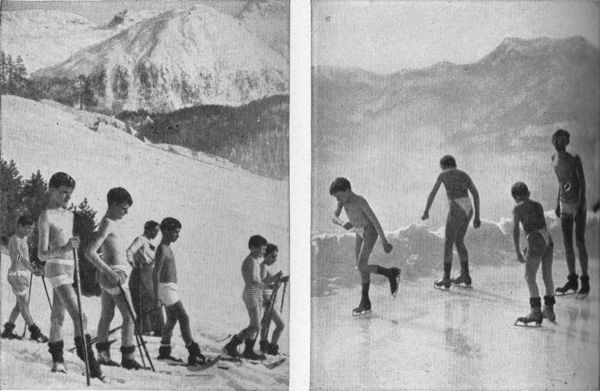

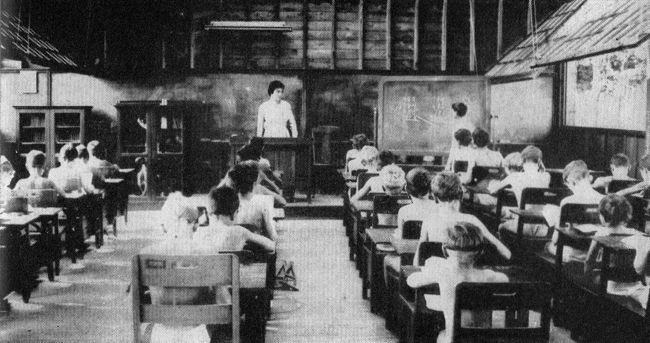

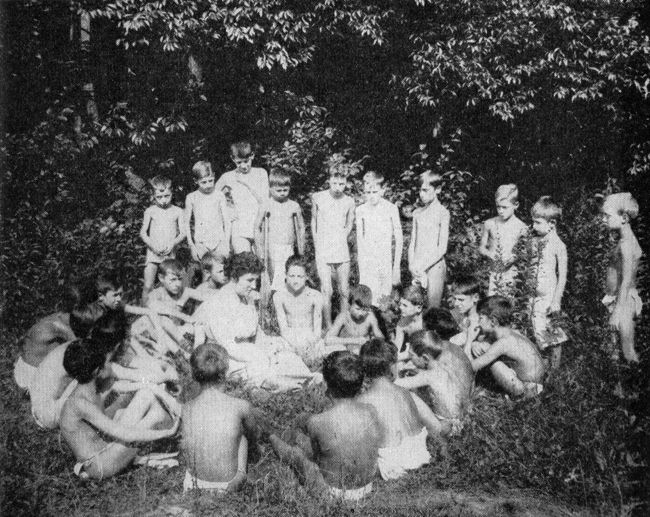

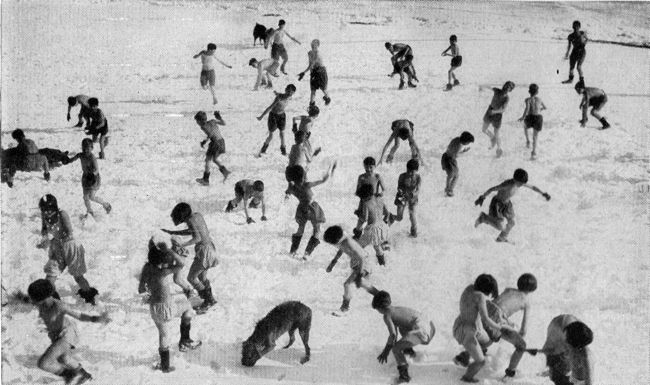

In a medical reference book from the 1940s, The New People's Physician (1941), I came across these pictures of kids in classrooms and playing sports dressed only in their tighty-whities. They weren't students at a clothing-optional school. They were actually being treated for tuberculosis. In the days before antibiotics, sunlight therapy (or heliotherapy) was a popular cure for that disease.

"At Leysin, in the Alpes Vaudoises, Dr. A. Rollier instituted the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis and other tuberculous diseases by means of direct sunlight. The patients spend as much time as possible in the open air, exposed to the rays of the sun."

"Early cases of tuberculosis in young and vigorous people benefit considerably from treatment at high altitudes. Exercise and sport of a not too strenuous nature is advocated."

"At Perrysburg, N.Y., tubercular children study in an open-air schoolroom, stripped to the waist."

"Minimum clothing and maximum exposure to the sun contribute to improving the health of these tuberculous children at Perrysburg, New York. Outdoor classes and fresh air improve general health as well."

"Outdoor air and sunlight, even in the New England winter, are part of the treatment for child tuberculosis patients of the Meriden State Tuberculosis Sanitarium, Meriden, Conn."

An LA Times article (May 28, 2007) gives some background on the popularity of sunlight therapy for TB:

Rollier devised a detailed protocol for how, exactly, to sunbathe for health. He was convinced that early-morning sun was best and that sun exposure was most beneficial when the air was cool. When patients, most of whom had tuberculosis, arrived at his solaria, they first had to adjust to the altitude (his clinics were in the mountains) and then to the cool air. Once acclimated, Rollier slowly exposed them to the sun.

The patients were rolled onto sun-drenched, open-air balconies, wearing loincloths and covered from head to toe with white sheets. On the first day of treatment, just their feet peeked out from under the sheets, and only for five minutes. On day two, the sheets were pulled a little higher, and the patients were left in the sun a few minutes more. By day five, only the patients' heads were covered, their bodies left to soak up sun for more than an hour. After a few weeks, the patients were very tan -- and hopefully very healthy. (The therapy worked for many, but not all.)

And according to a fairly recent article in the Journal of Cell Biology, "Curing TB with Sunlight" (Mar 27, 2006), sunlight actually is a fairly effective treatment for tuberculosis:

The finding may explain why Hermann Brehmer's 19th century trip to the Himalayas cured him of his TB, and why the fresh air at his sanatoria helped cure others. “Our forefathers knew a lot more about this than we give them credit for,” says Modlin. Eventually, however, sanitoria coddled their patients behind glass, which would have blocked the beneficial UV light.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 15, 2016 -

Comments (2)

Category: Medicine, Diseases

Corkscrew removes baseball

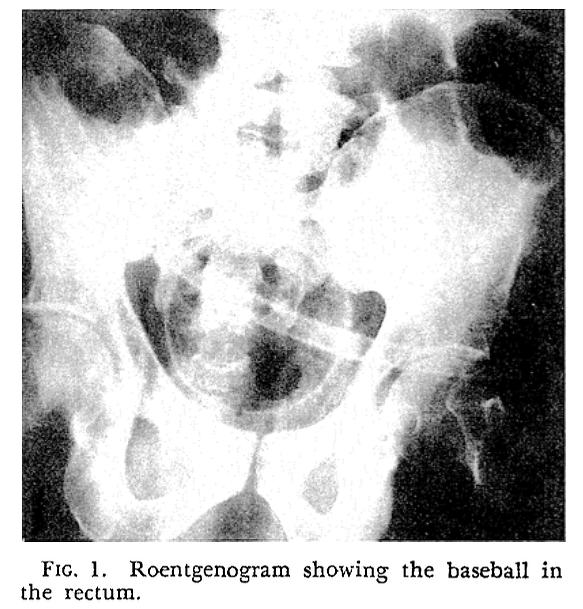

The following passage comes from "An Unusual Foreign Body in the Rectum — A Baseball: Report of a Case" (Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, January 1977):A Foley catheter was passed into the bladder and 800 ml of urine were removed. The patient then reluctantly described his recent activity. He and his sexual partner had celebrated a World Series victory of the Oakland Athletics by placing a baseball (hardball) in his rectum because, as he put it, "I'm oversexed."

The presence of the baseball was confirmed by radiography and proctologic examination. Under spinal anesthesia, the rectum was dilated and manipulations, including hooking the ball and pulling downward (enough to rip the cover of the ball), injecting air above the ball and giving downward traction, and obstetrical forceps delivery, failed.

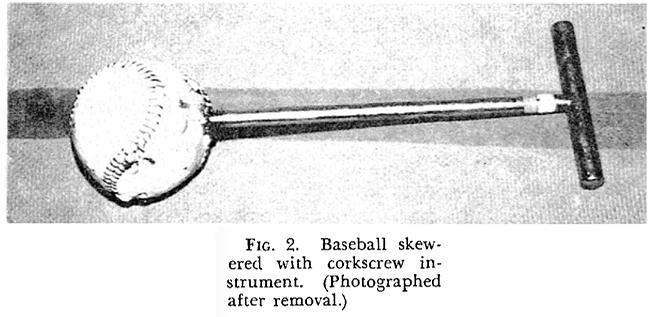

Through a midline abdominal incision, a low anterior colotomy was made directly on the baseball. The baseball, increasingly swollen by fluid, had lodged in the hollow of the sacrum above the levator muscles and below the true pelvic inlet. The baseball was skewered with a corkscrew instrument. An assistant exerted digital upward pressure through the rectum and, combined with a force enough to raise the patient off the table, the bali was delivered through the colotomy.

No gross fecal spillage occurred. The eolotomy was closed and the patient had an uneventful postoperative course. Gentamicin and clindamycin were given intravenously interoperatively and for five days postoperatively. Follow-up examination a year later revealed normal bladder and rectal functions.

The same article offers some other interesting bits of info later on:

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 10, 2016 -

Comments (10)

Category: Medicine, Sports

Tisket-a-Tasket

Posted By: Paul - Thu Apr 14, 2016 -

Comments (4)

Category: Humor, Medicine, Stereotypes and Cliches, 1940s, Genitals

Human Flesh Cure

The 1999 film Ravenous (starring Guy Pearce and Robert Carlyle) is about cannibalism. It's loosely inspired by the stories of the Donner Party and Alferd Packer. But it also includes the idea that eating human flesh can cure any wound or disease.I was reminded of that film when I came across this real-life case, from 1932, of someone trying the human-flesh cure, apparently successfully. But I wonder why the husband fed his wife only a third of his thigh steak? What did he do with the rest? Does eating too much human flesh turn someone into a vampire?

The Des Moines Register - Dec 25, 1932

Posted By: Alex - Fri Mar 11, 2016 -

Comments (7)

Category: Cannibalism, Medicine, 1930s

Paleo Diet of 1916

The idea that we'd all be healthier if we lived and ate like the cave man did has been around a long time. It long predates the current "paleo diet" trend.For instance, back in 1916, the makers of Nujol wanted everyone to believe that if you pooped a lot, like the cave man did, you'd be a model of health. Nujol was basically raw petroleum, which is why it was sold by the Standard Oil company. It's name meant "New Oil." Read more of Nujol's history here.

Source: Oregon Daily Journal - Sep 21, 1916

Posted By: Alex - Sat Dec 12, 2015 -

Comments (4)

Category: Medicine, 1910s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |