Medieval Era

A Five-Year Pregnancy

According to a sixteenth-century legend, recounted in the 1560 manuscript Histoires Prodigieuses by Pierre Boaistau, there once was a woman who suffered through a five-year pregnancy. Here's the story as summarized by Dr. Irvine Loudon in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (May 2003):Some days later, feeling her pains return, Marguerite summoned a series of most eminent doctors from far and wide, imploring their help. The doctors merely gave her a series of drugs but with no effect. Marguerite therefore 'resolved to let nature take its course and bore with exceeding pain for the space of four years this dead corpse in her stomach'. In the fifth year she finally persuaded a surgeon to open her up and remove the child which was 'half rotted away'. The operation took place on 12 November 1550. Marguerite soon recovered and was 'so full of life and so healthy that she can still [i.e. in 1559] conceive children'.

"The operation on Marguerite of Vienna"

As unlikely as the story may sound, Dr. Loudon argues that it could be true:

It may be that Marguerite’s dead baby was never delivered vaginally because it was never in the uterus. Being shut off, so to speak, from the outside world, a dead baby could have escaped being the source of an infection...

In this case, when a surgeon finally agreed to operate, he did not perform a caesarean section; he simply opened the abdominal wall and promptly saw and removed the remnants of the baby. The placenta would not have been a problem because in abdominal ectopics if the baby dies the placenta soon shrivels and can be left intact. This one had five years to shrivel.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Nov 09, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Medicine, Surgery, Medieval Era, Sixteenth Century, Pregnancy

The Unspeakable sin of Charlemagne

After the death of Charlemagne (in 814 AD), a legend emerged alleging that the ruler had committed some kind of "unspeakable sin."The legend first appeared in print in a 10th-century work called The Life of St. Giles. According to this work, Charlemagne had sought out St. Giles to ask the saint to pray for him because he had committed a sin so terrible that he had never been able to confess it properly. Giles reportedly agreed to pray for the king, even though Charlemagne didn't tell him what the sin was.

The fact that the unspeakable sin wasn't disclosed whet the imaginations of later medieval writers, creating a minor genre devoted to exploring what the sin was. Details from Charlemagne: Father of Europe (2022) by Philip Daileader.

The allegation of an incestuous relationship between Charlemagne and Gisela appears in the Karlamagnus Saga, a 13th century account of Charlemagne's life written in Norse. From there, the incest claim is then taken up by a number of different texts, especially French texts.

Other authors identified Charlemagne's unspeakable sin as necrophilia. That claim appears in a 14th century German poem about Charlemagne, "Karl Meinet," and the idea was then taken up in a number of 14th and 15th century German chronicles and treatises.

Specifically, someone had hexed Charlemagne by placing a charmed ring under the tongue of his dead wife. The ring caused Charlemagne to become infatuated with the wife and to continue the relations they had had while she was alive. When a bishop discovered the ring and removed it from the dead wife's mouth, Charlemagne became infatuated with the bishop. The bishop tossed the ring into a swamp, and Charlemagne became infatuated with the swamp, building a palace and dwelling there. To be clear, none of this is true...

One can only speculate as to why stories arose alleging that Charlemagne was guilty of incest or necrophilia, and why those stories gained a significant and distinguished audience. These stories did not emerge in or remain confined to a specific geographical milieu. They do not seem to have been concocted to achieve any specific political outcome. Perhaps they emerged primarily as a reaction against the overblown praise that Charlemagne received in other works. The bigger they come, the harder they fall.

Detail from a Flemish altarpiece (ca. 1400) showing Charlemagne asking St. Giles to pray for him.

Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Posted By: Alex - Fri Sep 29, 2023 -

Comments (3)

Category: Medieval Era, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore

Charlemagne’s asbestos tablecloth

Legend has it that Charlemagne owned an asbestos tablecloth. This allowed him to perform an unusual party trick. After hosting a feast, he would entertain his guests by throwing the tablecloth in the fire. All the food and stains would burn off, but the cloth itself didn't burn. When removed the fire it was not only undamaged but also sparkling clean.The story can be found in a lot of sources, such as in the eleventh edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica (1911), in the article about asbestos. Or in the newspaper article below.

Vancouver Daily Province - Mar 27, 1940

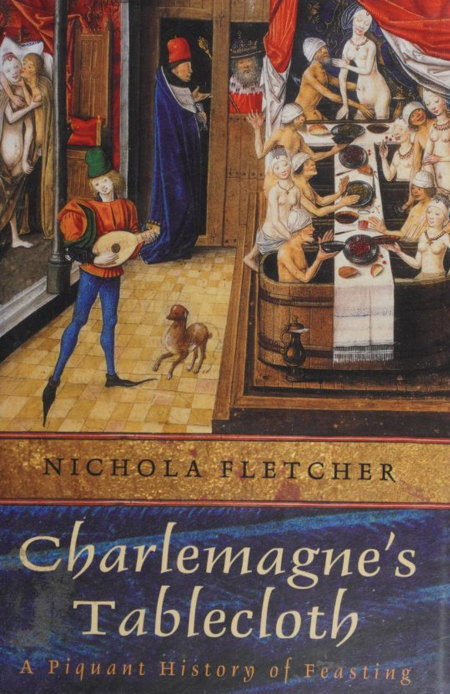

But is there any truth to the legend? The best answer to this question I could find is in the book Charlemagne's Tablecloth (2004) by Nichola Fletcher. Most of the book isn't actually about Charlemagne (it's about the history of feasting), but in the afterword she looks specifically at the legend.

She notes that the ancient Greeks and Romans had created cloth out of asbestos. Pliny the Elder wrote about the existence of asbestos napkins. So it's possible that Charlemagne had an entire tablecloth made from the material. However, she was unable to find any reference to the story in medieval sources about Charlemagne. Frustrated, she eventually requested help from Donald Bullough, an expert on Charlemagne who taught at St. Andrews University. This was Bullough's reply:

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 14, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Medieval Era, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore

Acoustic Skulls

When excavating medieval and early-modern buildings in northern Europe, archaeologists sometimes find horse skulls buried beneath them. One theory is that the skulls were placed there for magical, ritualistic reasons. Another possibility is that they served an acoustic purpose.Sonja Hukantaival discusses this in her 2009 article "Horse Skulls and 'Alder-Horse': The Horse as a Building Deposit".

In churches the acoustics were very important, of course. And in houses were people danced and music was played, but why in threshing barns? It was considered important that the sound of threshing carried far. Could this have some magic purpose? It is well known that in many cultures loud noises are considered to expel evil forces. So this "practical" custom of acoustic skulls may not be contradictory to magical and symbolic acts at all. One question to consider is also why horses' skulls were preferred. One would presume that the skulls of cattle would be available more often than those of horses, and possibly just as suitable for acoustics.

More info: IAC Archaeology

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jan 10, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Medieval Era, Archaeology

St. Rumwold—the youngest saint

Due to the vagaries of medieval spelling, Rumwold is also known as Rumald, Rumbold, Grumbald, Rumbald, etc. The story goes that Rumwold was born in 662 and only lived for three days. But during that brief time he demonstrated the ability to speak and recited the Lord's Prayer. So, after his death, he was made a saint.

image source: .johnsanidopoulos.com

While a three-day-old saint is, on its own, odd enough, my favorite part of his story involves the picture of him that later hung in Boxley Abbey in Kent. It was used as a test of a woman's chastity. Those who were chaste would easily be able to lift the picture. But if a woman was not chaste, the picture would mysteriously become so heavy that she wouldn't be able to lift it.

The secret, unknown by those trying to lift the picture, was that it could be held in place (or not) by a wooden rod concealed behind it.

The story of the unliftable portrait is told by Sidney Heath in Pilgrim Life in the Middle Ages (1911):

His image at Boxley is said to have been small, and of a weight so light that a child could lift it, but that it could at times become so heavy that it could not be moved by persons of great strength.

Thomas Fuller, the quaint old divine, tells us that "the moving hereof was made the conditions of women's chastity. Such who paid the priest well might easily remove it, whilst others might tug at it to no purpose. For this was the contrivance of the cheat — that it was fastened with a pin of wood by an invisible stander behind. Now, when such offered to take it who had been bountiful to the priest before, they bare it away with ease, which was impossible for their hands to remove who had been close-fisted in their confessions. Thus it moved more laughter than devotion, and many chaste virgins and wives went away with blushing faces, leaving (without cause), the suspicion of their wantonness in the eyes of the beholders; whilst others came off with more credit (because with more coin), though with less chastity."

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 01, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Babies, Hoaxes and Imposters and Imitators, Religion, Medieval Era

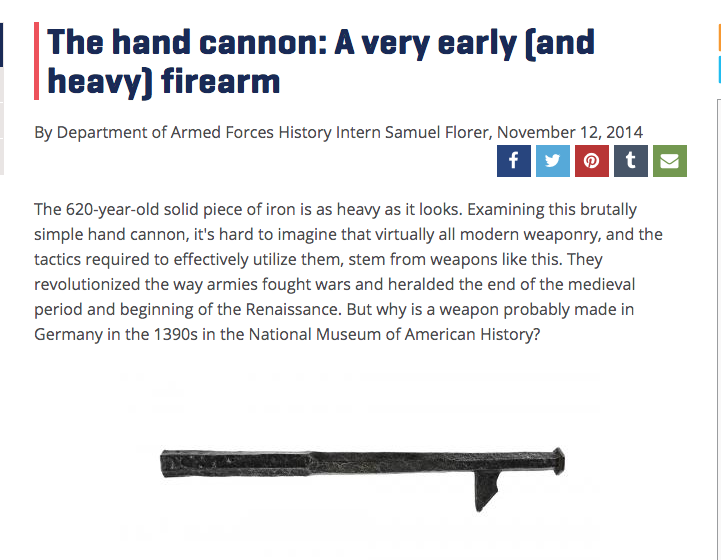

The Hand Cannon

Smithsonian article.

Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Feb 22, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Medieval Era, Renaissance Era, Asia, Europe, Weapons

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |