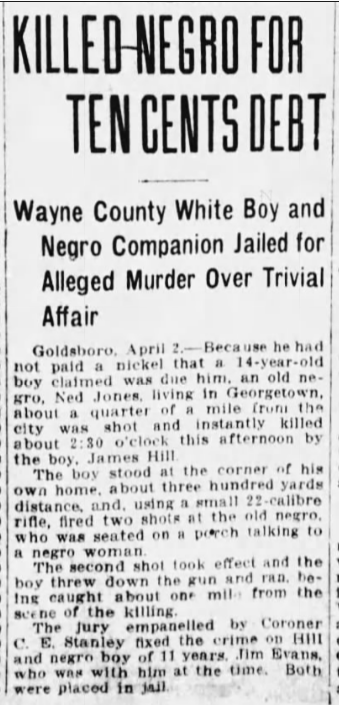

Money

Unlikely Reasons for Murder No. 13

Source: The News and Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina)03 Apr 1912

Posted By: Paul - Thu Mar 23, 2023 -

Comments (3)

Category: Death, Money, Teenagers, 1910s

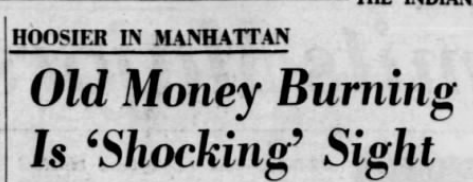

Old Money

Article source: The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) 09 Dec 1959, Wed Page 31

Posted By: Paul - Thu Dec 15, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Destruction, Government, Money, 1950s

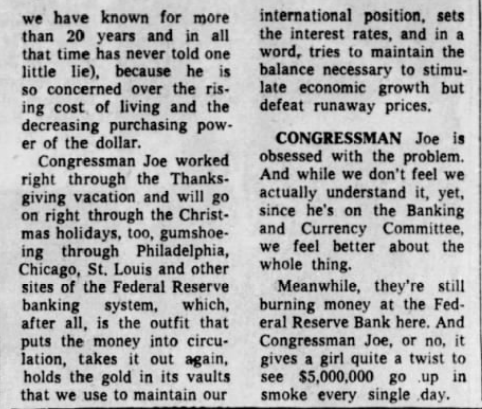

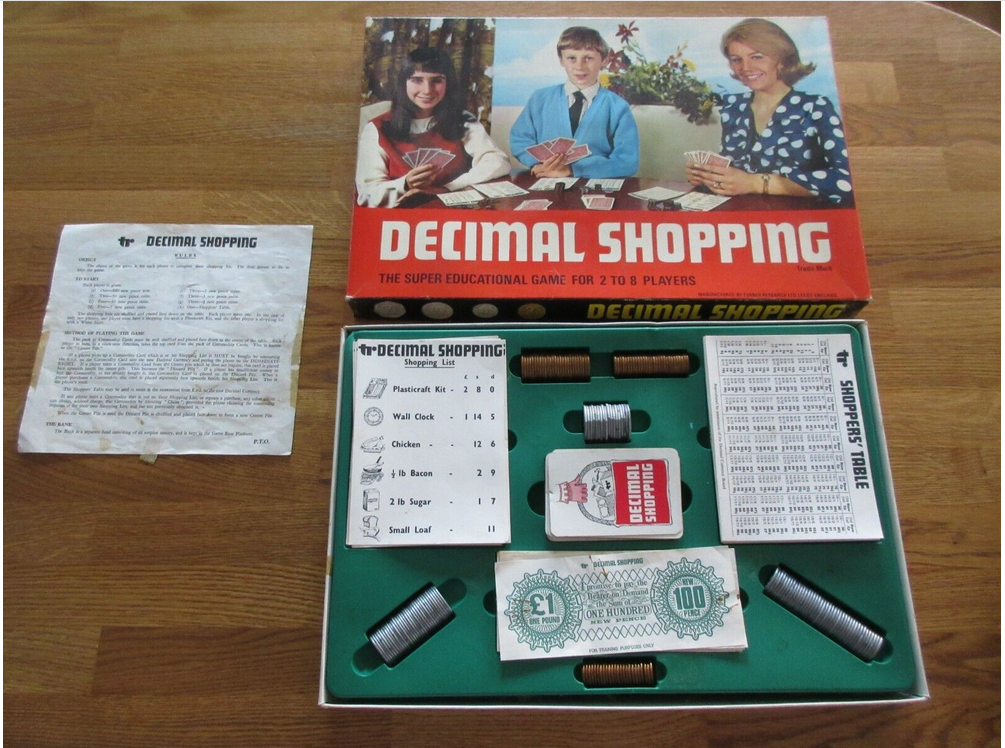

The Decimal Shopping Game

When the UK made its switch from old-style currency to decimal currency, this board game was issued to help familiarize people with the new mode.Currently, a copy is for sale at UK eBay, where more pix await your inspection.

Board Game Geek has just a placeholder entry.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Dec 08, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Boredom, Games, Money, 1970s, United Kingdom

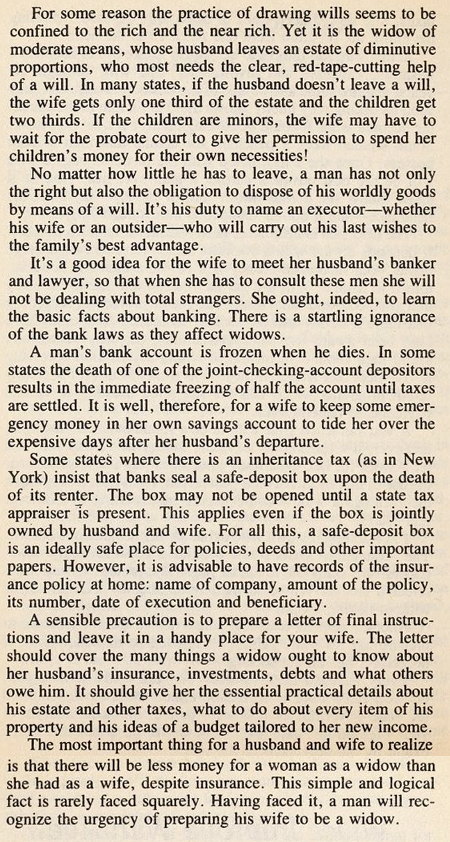

Teach your wife to be a widow

Donald L. Rogers was financial editor of the New York Herald Tribune. He originally wrote "Teach your wife to be a widow" as an article for Collier's Magazine, and later expanded it into a book (1952).

The article (and book) urged husbands to educate their wives about finances, so that in case the husband died the wife wouldn't end up going destitute.

I think Jean Mayer's article, "How to murder your husband," pairs particularly well with it. Both appeared in the 1981 Reader's Digest collection, Love and Marriage.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Dec 04, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Money, Husbands, Wives, Books, Marriage

Trapdoor for bank tellers

I'm aware of quite a few inventions designed to trap or incapacitate bank robbers. But the idea of allowing a bank teller to abruptly vanish is more novel.Of course, this approach could only work if there was a single teller working, and hopefully no other customers in the bank.

I was curious whether this bank with the cashier trapdoor might still exist, but I had no luck finding its address. I did find that it was acquired by another bank in 1948. So it was probably demolished long ago.

Hagerstown Morning Herald - Aug 9, 1932

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 28, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Crime, Inventions, Money, 1930s

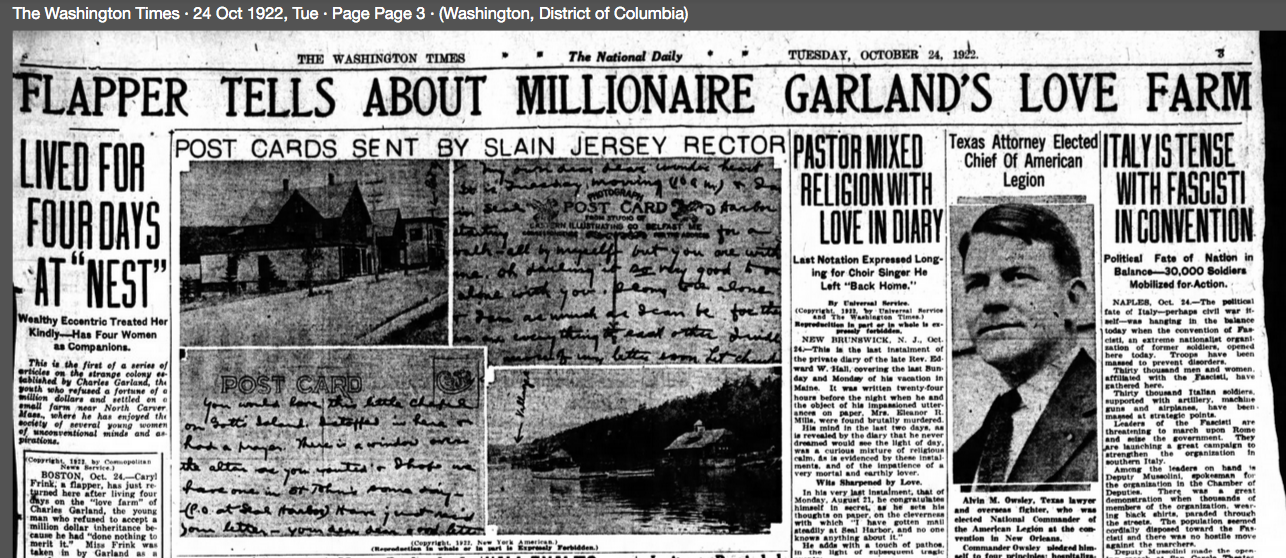

Charles Garland and his Love Farm

Elon Musk, stand back!If you inherited a ton of money at a young age, you too might be confused about how to live. At first, you might radically decide not to accept the fortune. Then, you might decide to use it for charitable purposes. Finally, you might opt to establish a free-love commune.

That's the path that one Charles Garland took. Read his whole story at Wikipedia.

After his separation from his wife, Garland established two successive agricultural communes, or "colonies of idealists", both named April Farm.[19] The first April Farm, in which Garland lived from January 1922, was at North Carver, Massachusetts.[22] In 1924, Garland moved to a new "April Farm" in Lower Milford Township, Pennsylvania.[19]

Garland scandalized polite society by inviting young women to live with him at these colonies, where he planned to "work out the problems of life".

Naturally, newspapers had a field day with all this.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Nov 10, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Money, Communes, Utopias, and Other Alternative Societies, Public Indecency, Bohemians, Beatniks, Hippies and Slackers, 1920s

Miss Drive-In Teller

According to wikipedia, drive-through windows began appearing at banks in the early 1930s. By 1958, over 4000 women were working as drive-in tellers, and that's the year that the Mosler Safe Company sponsored the first nationwide "Miss Drive-In Teller" contest.Contestants were judged on "personality, courtesy, and efficiency." And, of course, appearance. The winner got a two-week all-expense-paid trip for two to Havana, Cuba. Plus $500 in spending money. So it attracted quite a few contestants. In later years, winners went to places like Bermuda and Norway.

Marion Polk, a teller at Peoples National Bank in Rock Hill, South Carolina, became the first Miss Drive-In Teller. She must have been fairly proud of this because it's mentioned in her obituary. The contest continued to be held annually until 1972 (as far as I can tell) when Jacqueline Fleming became the final Miss Drive-In Teller.

Marion Polk, Miss Drive-In Teller of 1958

Columbia Record - Oct 4, 1958

Tamra Evans, Miss Drive-In Teller of 1961

Wausau Daily Herald - Oct 3, 1961

San Rafael Daily Independent Journal - June 27, 1961

Susan Erickson, Miss Drive-In Teller of 1962

Corvallis Gazette-Times - Aug 16, 1962

Jean Doggett, Miss Drive-In Teller of 1964

Morgan City Daily Review - July 3, 1964

Jeanie Archer, Miss Drive-In Teller of 1966

Racine Journal Times - Sep 1, 1966

Jacqueline Fleming, Miss Drive-In Teller of 1972

Sioux City Journal - Oct 23, 1972

Posted By: Alex - Fri Sep 30, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Money

The Hypnotic Powers and/or Memory-wiping Drugs of Cool Whip

Posted By: Paul - Sat Sep 10, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Family, Hypnotism, Mesmerism and Mind Control, Money, Propaganda, Thought Control and Brainwashing, Advertising, Junk Food, 1970s

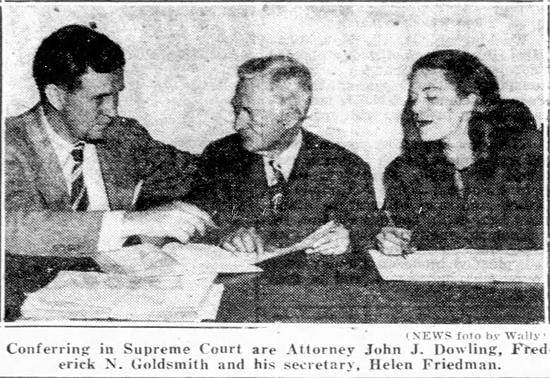

Using comic strips to forecast the stock market

Frederick N. Goldsmith published a successful stock-market newsletter from 1916 to 1948, when he came under investigation by the New York Attorney General for telling his subscribers that his market advice was based on "inside information."Goldsmith, however, had an unusual defense. He revealed that the primary source of his inside information was the comic strip "Bringing Up Father." Goldsmith believed that the comic strip provided clues, in code, about the direction of the market. The clues had been placed there by "big insiders." This was apparently their way of communicating with each other. But Goldsmith believed he had cracked the code. Details from The Manipulators (1966) by Leslie Gould:

In one episode, explained Goldsmith, Jiggs was at the theater and remarked: "The intermissions are the only good thing about this show." Goldsmith interpreted that as a sure-fire tip to buy Mission Oil, which he passed on to his market letter subscribers. It went up fifteen points the next day.

When questioned, McManus (author of the comic-strip) insisted he knew nothing about the stock market and pointed out that he prepared his strip nine weeks ahead of publication. He also noted, "What would I be doing with cartoons if I were so hot on the stock market?"

Having learned the truth, the AG could have dropped the case, but he decided to shut down Goldsmith anyway for misleading his subscribers.

NY Daily News - Nov 18, 1948

The problem that the AG faced at the trial, however, was that Goldsmith's predictions had actually been pretty good and had served his subscribers well. In fact, many of his subscribers came to his defense during the trial. Nevertheless, the judge shut down Goldsmith's business. More details from The Manipulators:

The defendant. . . was engaged in the business of writing and distributing a market letter to the public which attempted to forecast and predict future prices of securities and commodities.

Subscribers were led to believe that the defendant used statistics, financial reports and charts in preparing. . . prognostications of future price movements. The letter was also so worded as to imply that the defendant had sources of special and secret information concerning stock movements. . .

The subscribers to the defendant's daily market letter had the right to assume that the defendant possessed a superior knowledge of the stock market, that whatever information he had came from living persons and recognized sources and not as a result of interpretations of comic strips. When he failed to inform his subscribers of the alleged sources of information he was concealing a material fact.

Terre Haute Tribune - June 13, 1948

Posted By: Alex - Mon Sep 05, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Money, Comics, 1940s

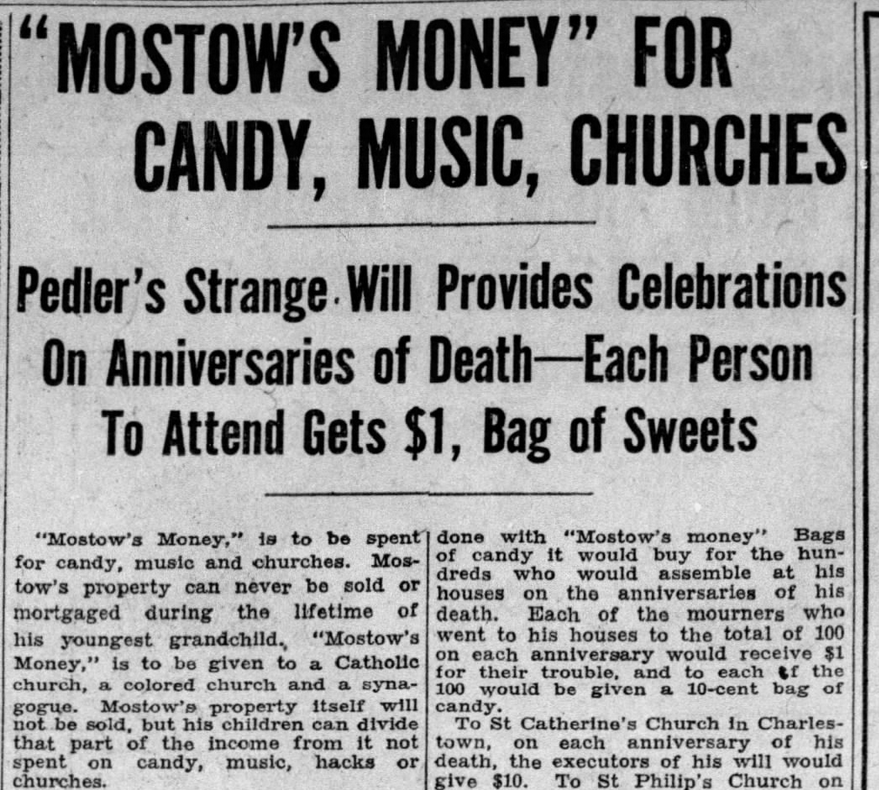

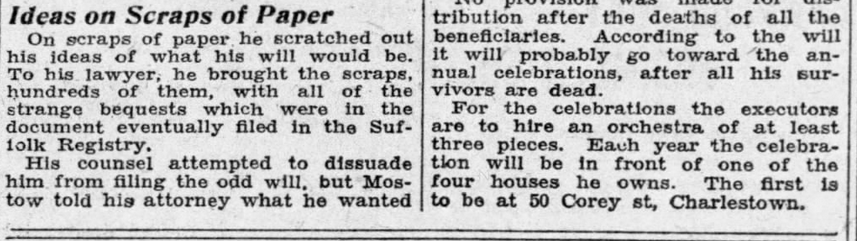

The Strange Will of John Mostow

Source: The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts)04 Apr 1928, Wed Page 16

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jul 06, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Eccentrics, Law, Money, Candy, 1920s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |