Odd Names

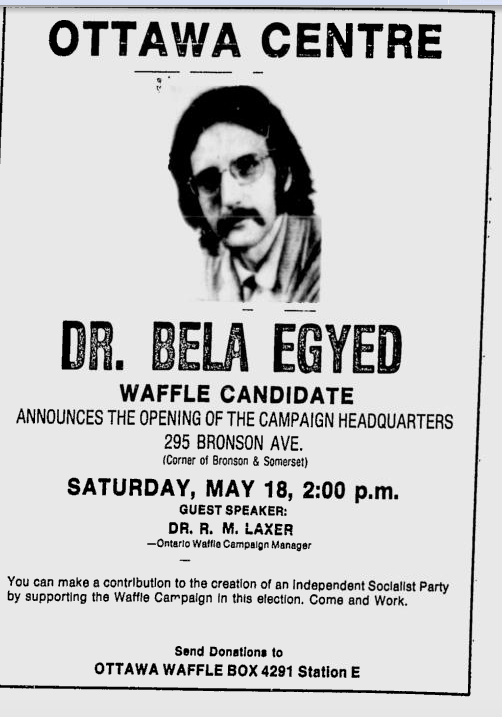

The Waffle Party

With all this talk of rogue Republicans forming a new party, I hope they choose a name as evocative as that of Canada's The Waffle.

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Feb 12, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Odd Names, Politics, 1960s, 1970s, North America

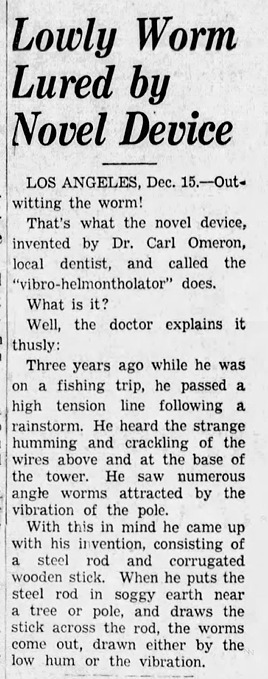

The Vibro-Helmontholator

A fancy name for a worm catcher.

The Elizabethton Star - Jan 12, 1938

San Francisco Examiner - Dec 16, 1937

Posted By: Alex - Thu Dec 10, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Inventions, Odd Names, 1930s

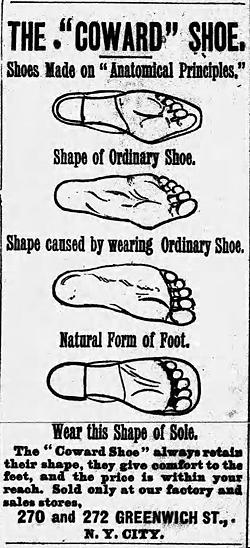

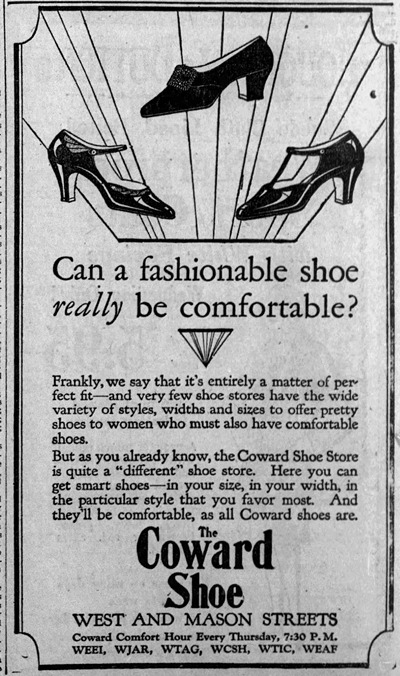

The Coward Shoe

In 1866, cobbler James S. Coward opened a store in New York City. He named it after himself, and he referred to the shoes he sold as "Coward shoes".Despite the odd name, his business did extremely well. In fact, it endured almost to the present. As of 2014, the company had both a twitter and facebook page. But their website now redirects to Old Pueblo Traders whom, I'm guessing, must have acquired them.

The Keyport Weekly - Apr 23, 1892

Boston Globe - Sep 20, 1927

Posted By: Alex - Wed Nov 25, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Odd Names, Shoes

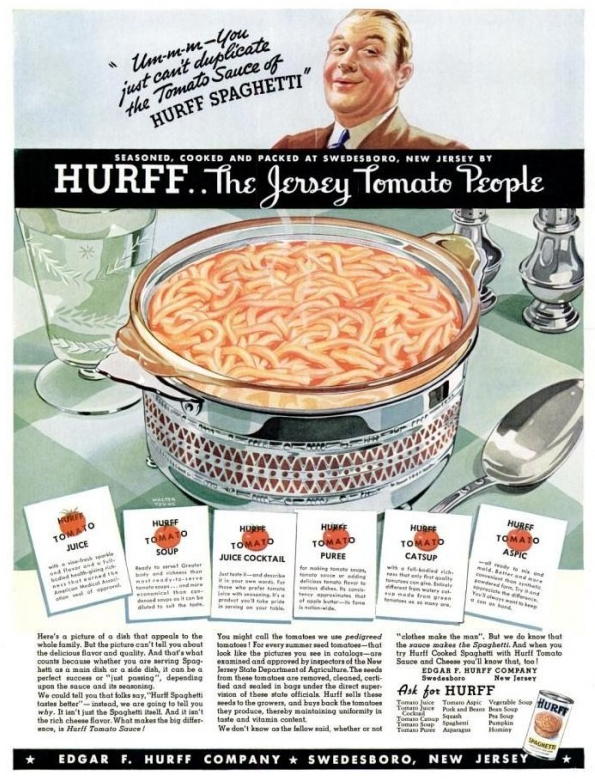

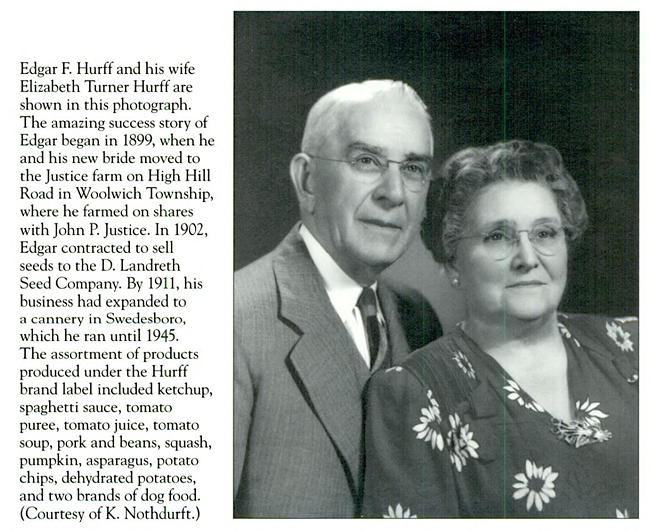

Hurff Foods

Hurff... It's not a name, one would think, that would lend itself to selling food. Though it didn't seem to hurt Edgar Hurff's food business, which flourished until 1948. It was then sold to Del Monte, which evidently opted not to keep the Hurff name.

Source: Swedesboro and Woolwich Township

Posted By: Alex - Wed Nov 11, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Odd Names

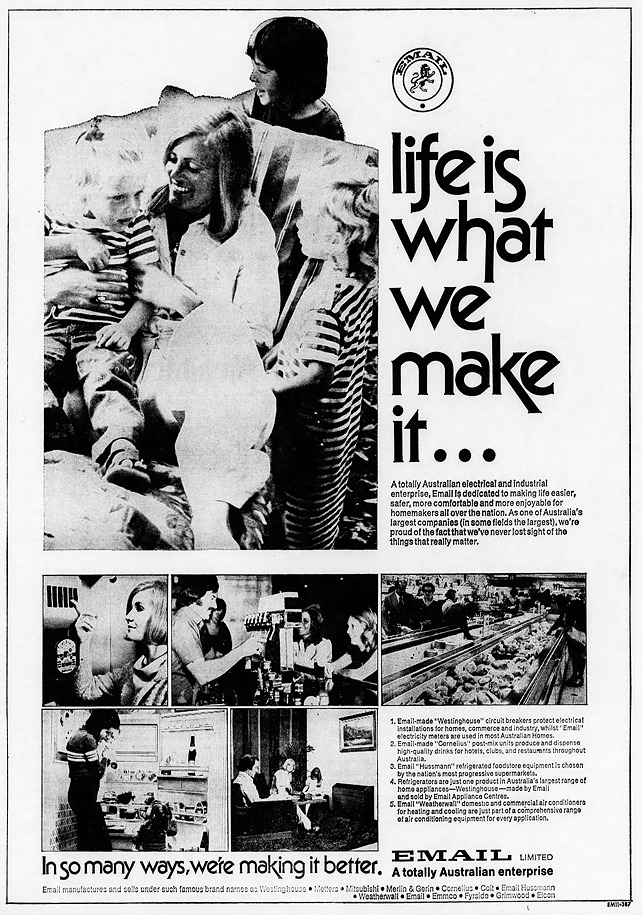

Email Limited

It's not clear who first used the word 'email' to refer to electronic mail. The entrepreneur Shiva Ayyadurai has taken credit since, in 1978, when he was a 14-year-old high school student in New Jersey, he built an electronic mail software program that he called 'EMAIL'.Actually, Ayyadurai goes further and claims he not only coined the term but also invented the very concept of email. But there's a lot of skepticism about his claims.

However, what is clear is that the term 'email' was in use for decades before 1978, although not to refer to electronic mail. It was the name of a large Australian company that specialized in making meters for gas, water, and electricity. The name was an acronym that stood for 'Electricity Meter & Allied Industries Ltd.'

The tagline of the company was "Email — a totally Australian enterprise." Wikipedia notes: "At one time there would have been few houses in Australia which did not have an Email meter."

Sydney Morning Herald - July 11, 1977

Posted By: Alex - Fri Apr 24, 2020 -

Comments (6)

Category: Odd Names

Sprink

I wonder how much consumer research this company did before deciding to name their product 'Sprink'. I'm guessing they thought it was a catchy shortened form of 'sprinkle'. But the problem is that the name sounds too much like 'Stink', which is exactly the wrong association for a room-rug freshener. Must be why it doesn't seem to have been on the market more than a few months.

Rocky Mount Telegram - June 18, 1963

Cincinnati Enquirer - Oct 21, 1962

Posted By: Alex - Fri Feb 14, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Odd Names, Products, Fetishes, 1960s

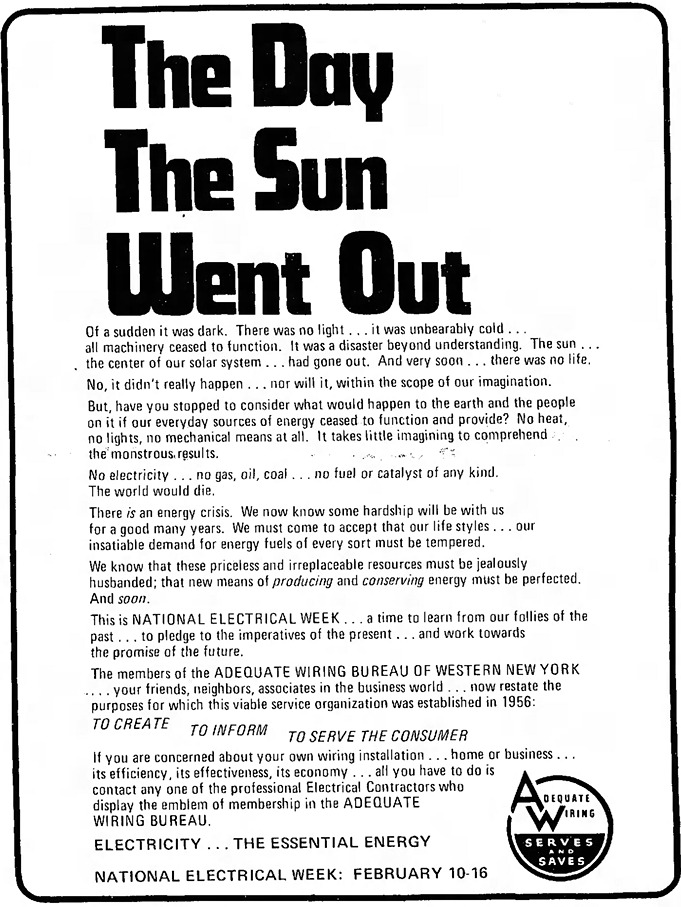

The Adequate Wiring Bureau

Nowadays, to describe something as 'adequate' sounds like it's damning with faint praise. It doesn't come across a ringing endorsement. It's like getting a 'B' on a homework assignment instead of an 'A'. It's merely adequate, not great.But evidently the word once had a much stronger positive association in general usage, as seen in the existence of the National Adequate Wiring Bureau. Many states also had their own Bureaus of Adequate Wiring. Their goal was to encourage homes to have proper, code-compliant electrical wiring.

As far as I can tell, the National Adequate Wiring Bureau came into existence as early as the 1890s, but there is no such thing today. By the 1970s, Adequate Wiring Bureaus had quietly begun to change their names, dropping the word 'adequate'.

It reminds me of the "Miss Typical" awards that used to be bestowed on young women. In today's culture, being typical or adequate no longer sounds like a compliment.

Brandon Times - Mar 12, 1953

I like this 1974 ad from the Adequate Wiring Bureau of Western New York, which used the idea of the sun suddenly going out, and the Earth being plunged into a freezing-cold apocalypse, as a way to promote the need for adequate wiring.

Wellsville Daily Reporter - Feb 13, 1974

Posted By: Alex - Sat Sep 28, 2019 -

Comments (1)

Category: Languages, Odd Names, Public Utilities, Power Generation

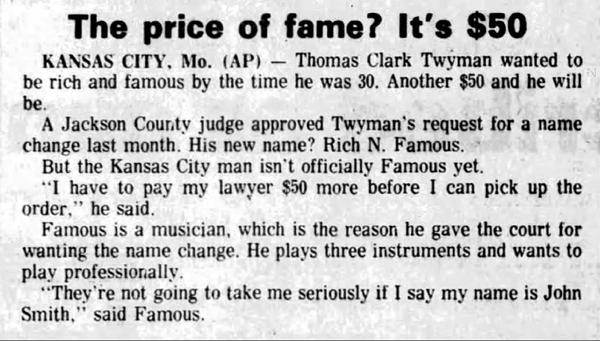

How to become Rich ‘N Famous

Change your name, of course.

Mason City Globe-Gazette - Mar 31, 1981

As far as I can tell, Thomas Clark Twyman never did live up to his changed name. Actually, it’s not even an original gag. I found several musicians (such as the one below, from Australia) calling themselves Rich N. Famous.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Apr 09, 2019 -

Comments (0)

Category: Odd Names, 1980s

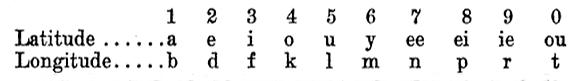

Stedman Whitwell’s Rational System of Nomenclature

Back in the 19th century, English architect Stedman Whitwell decided that there must be a way to name cities and towns that could not only provide a unique name but also convey geographic information. His idea, as described by George Browning Lockwood in The New Harmony Communities (1902):

The first part of the town name expressed the latitude, the second the longitude, by a substitution of letters for figures according to the above table. The letter “S” inserted in the latitude name denoted that it was south latitude, its absence that it was north, while “V” indicated west longitude, its absence east longitude.

Extensive rules for pronunciation and for overcoming various difficulties were given. According to this system, Feiba Peveli indicated 38.11 N., 81.53 W. Macluria, 38.12 N., 87.52 W., was to be called Ipad Evenle; New Harmony, 38.11 N., 87.55 W., Ipba Veinul; New Yellow Springs, Green county, Ohio, the location of an Owenite community, 39.48 N., 83.52 W., Irap Evifle; Valley Forge, near Philadelphia, where there was another branch community, 40.7 N., 75.25 W., Outeon Eveldo; Orbiston, 55.34 N., 4.3 W., Uhi Ovouti; New York, Otke Notive; Pittsburg, Otfu Veitoup; Washington, Feili Neivul; London, Lafa Vovutu.

The principal argument in favor of the new system presented by the author was that the name of a neighboring Indian chief, “Occoneocoglecococachecachecodungo,” was even worse than some of the effects produced by this “rational system” of nomenclature.

I think the chart above is slightly misleading, as it implies that the top line is for latitude and the bottom for longitude. But if you look at the names Whitwell was coming up with, it's clear that this wasn't the case. It seems, instead, that one had to choose whether to start the name with a vowel (top line) or consonant (bottom line).

If I've understood his system correctly, then the 'rational' name for San Diego (32.71 N, 117.16 W) could be Fena Baveeby. And Los Angeles (34.05 N, 118.24 W) could be Fotu Avapek.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Mar 20, 2019 -

Comments (4)

Category: Geography and Maps, Odd Names, Nineteenth Century

Pho Keene Great

For some reason, the city of Keene, New Hampshire is objecting to a Vietnamese restaurant's plan to call itself Pho Keene Great.More info: nhpr.org

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jan 04, 2019 -

Comments (8)

Category: Innuendo, Double Entendres, Symbolism, Nudge-Nudge-Wink-Wink and Subliminal Messages, Odd Names

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |