Patents

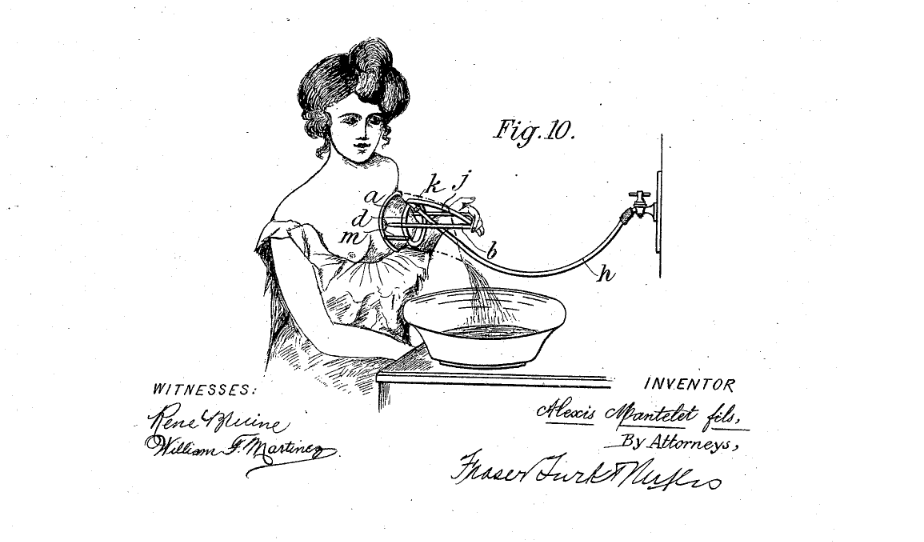

Breast Douche

When a simple washcloth just won't do.Full patent is here.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Aug 11, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Body, Hygiene, Patents, 1910s

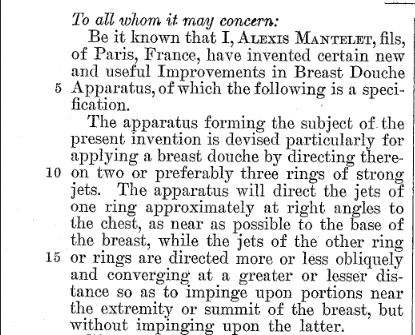

Spanking Toy

Although cats are featured in the drawing, the inventor wants you to know the figures may be generalized to other animals or humans.The patent is here.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jul 27, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Anthropomorphism, Inventions, Patents, Toys, Sadism, Cruelty, Punishment, and Torture, 1900s

Portable Oasis

The "portable oasis" of Belgian artist Alain Verschueren consists of a small, plexiglass greenhouse that he wears over his head. He came up with the idea around 2005, but only got attention for it in 2020, due to Covid, when he began wearing it around town instead of a mask.More info: Alain Verschueren, Reuters

I'll give Verschueren the benefit of the doubt and assume he wasn't aware of Waldemar Anguita's "greenhouse helmet," patented in 1986. The two ideas are basically identical.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jul 24, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Art, Inventions, Patents

Darrell Johnson’s Mechanical Listener

Darrell Johnson knew that, if you have to give a speech, it helps to practice it first in front of someone. But sometimes you can't find a willing listener. That's where his 'mechanical listener' came in. It was a sculptured head with eyes that would light up and eyelids that would flutter in response to the sound of a human voice. These movements, he reasoned, would "portray a feeling of life, participation, and cooperation to thereby stimulate expression relative to the topic or subject under consideration with resultant improvement and intensity of such expression."He was granted Patent No. 2,948,069 for this invention in 1960.

It would be interesting to know if a prototype of this thing still survives, hidden away in someone's attic.

Arizona Daily Star - Aug 14, 1960

Springfield Daily News - Oct 16, 1960

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jul 15, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Patents, AI, Robots and Other Automatons, 1960s

Automatic Washing Machine for Dogs

Mario Altissimo was granted Patent No. 4,505,229 in 1985 for his "Automatic Washing Machine for Dogs and Like Animals".I wonder if anyone has ever created an equivalent type of automatic washing machine for humans.

Science Year 1983

Update: Paul gave me a heads up about this Three Stooges take on a washing machine for dogs. A clear example of prior art!

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jun 13, 2022 -

Comments (5)

Category: Bathrooms, Patents, Dogs, 1980s

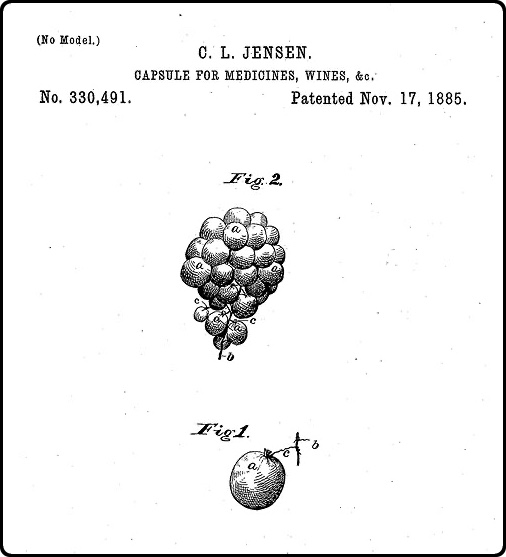

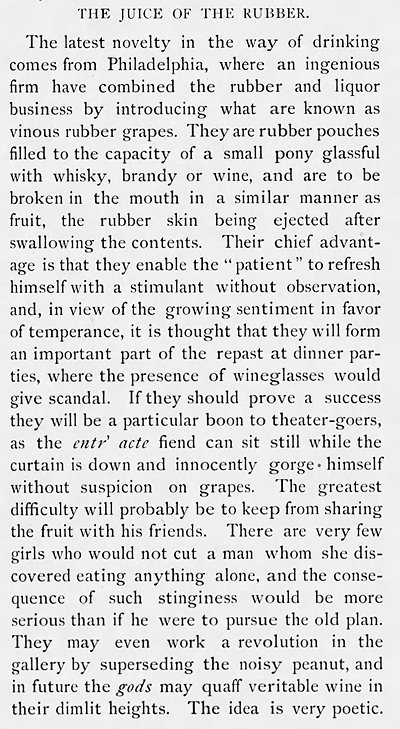

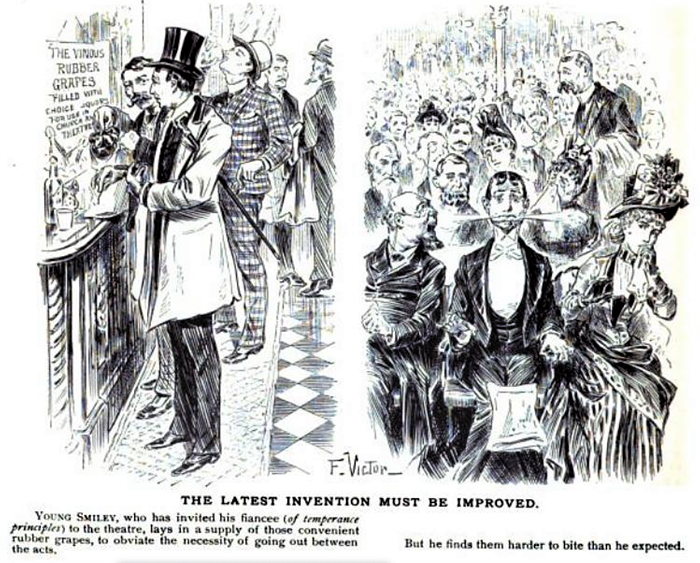

Vinous Rubber Grapes

Vinous Rubber Grapes, patented in 1885, were rubber grapes filled with various types of alcohol (wine, brandy, whisky, etc.). The idea was that they would allow people to drink discreetly even in places where alcohol wasn't served. Or, as the advertising copy put it, the rubber grapes provided "a ready means for a refreshing stimulant whenever needed, without reservation, even in the most criticising surroundings."Apparently they sold quite well, right up until the passage of the 18th amendent in 1920.

I don't think that anything quite like them can be bought nowadays.

The Topeka Lantern - Feb 19, 1887

The Judge's Library - Apr 1889

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jun 01, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Inebriation and Intoxicants, Patents, Nineteenth Century

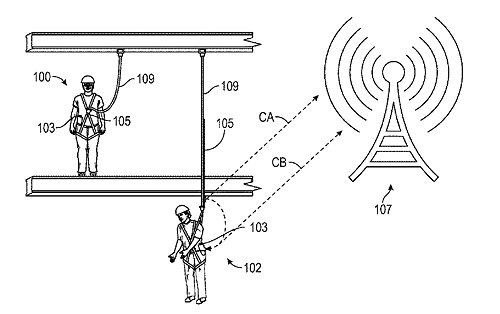

Electricity from falling workers

3M recently received a patent (No. 11,260,252) for a safety harness that generates electrical power when a worker (wearing the harness) falls off a building.

Digging deeper into the patent, it becomes clear that 3M is imagining that if the safety harness is self-powered, it can readily transmit a help message. As opposed to it being battery-powered, which runs the risk of the battery being dead when needed.

Still, it's amusing to think of falling workers as the solution to the world's energy problems.

Posted By: Alex - Wed May 04, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Patents, Power Generation

Anti-Submarine Seagulls

During World War I the British Navy attempted to train seagulls to reveal the presence of German submarines. The idea was to use a dummy periscope "from which at intervals food would be discharged like sausage-meat from a machine." The birds would, hopefully, learn to associate periscopes with food and would then fly around approaching German submarines, revealing where they were.Initial tests were conducted by Admiral Sir Frederick Inglefield in Poole harbour in Dorset. Inglefield tried to train the birds not only to fly around periscopes, but also to poop on them.

Subsequent tests were briefly conducted in 1917, but then the Navy abandoned the idea.

One private inventor, Thomas Mills, refused to give up on the idea. In 1918 he patented what he called an "apparatus for use in connection with the location of submarines" (Patent GB116,976). It was basically a dummy periscope that disgorged ribbons of food.

Unfortunately for Mills, the development of sonar then made submarine-detecting seagulls unnecessary.

More info: "Avian Anti-Submarine Warfare Proposals In Britain, 1915-18: The Admiralty And Thomas Mills," by David A.H. Wilson in the International Journal of Naval History - Apr 2006, 5(1).

Thomas Mills' seagull-training device

Mills and his invention

Posted By: Alex - Wed Apr 27, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Military, Patents, 1910s

Dragan Petrik’s Ice Railroad

In 1967, Dragan Petrik was granted a patent (No. 3,343,495) for a high-speed, rocket-powered train that would run on blocks of ice. In an Oct 1967 column, NY Times reporter Stacy V. Jones provided some details:Dragan R. Petrik of Pretoria was granted a patent last week for vehicles equipped to change the blocks as they melt and wear down, without stopping the train.

Patent 3,343,495 provides for propulsion by jet, rocket thrust, propellers or other means independent of the usual wheel traction. While conventional rails could be used, Petrik prefers a flanged metal surface that can be heated in cold climates.

Each car is to have cold rooms for storage of the ice. Blocks are to be forced down through ducts under control of a sensing unit that maintains the car at proper height.

Conventional wheels may be used in a station or for emergency support. A set of ice blocks is provided just ahead of and in back of each set of wheels. One ice skid can be used while another is being replenished.

For braking, there is a rubbing surface along the track, on which friction pads can be applied.

Petrik says his system will make possible very high speed for all types of land vehicles.

I have no idea if this would work, but it would be interesting to see it tested out.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Apr 17, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Patents, Trains and Other Vehicles on Rails, 1960s

Joke Beer

It's April Fool's Day. Have a beer!From Patent No. 2,140,327:

Posted By: Alex - Fri Apr 01, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Holidays, Patents, 1930s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |