Patents

Sardine-Flavored Ice Cream

In 1994, the Japanese Patent Office granted Sato Shigeaki a patent for sardine-flavored ice cream. In his patent application, Shigeaki explained that his intention was to to promote the fishing industry by encouraging children who don't like fish to eat them. He also provided the basic recipe for his sardine ice cream. It involved cooking the sardines with onions, soybeans, rice wine, and walnut paste. Then adding this concoction to a base of chocolate ice cream.This patent enjoys a somewhat unusual distinction. In 1997, European patent examiner Bernard Delporte revealed that it was the most common search request received by his office. He added, "No one believes that it actually exists until they've called it up and seen it themselves."

However, further research reveals that sardine ice cream was just the tip of the iceberg of Sato Shigeaki's grand vision. Apparently he imagined using oddball ice cream flavors to boost a broad range of different industries. As seen by the other patents he was granted:

PURPOSE: To enable sales of an ice cream in different types of industries such as the lumber industry and the paper-manufacturing industry, to promote activation of enterprises and to sell the ice cream as a prescribed commodity as a local product by combining white ceder as a tree with ice cream to develop an epoch-making food.

CONSTITUTION: This ice cream is obtained by mixing a naturally extracted edible white ceder spice with an ice cream, mixing a pie dough with an edible white ceder spice, baking the mixture to give a pie, grinding the pie and mixing the flour with an ice cream or combining these ice creams with a designed cake forming a leaf or a twig of white ceder.

JPH06233656A: Sunflower Ice Cream

PURPOSE: To obtain an ice cream of sunflower as a local product.

CONSTITUTION: An ice cream base comprising honey of sunflower is mixed with a sunflower paste prepared by making seeds of sunflower into a paste to give an ice cream. The ice cream is topped with a material obtained by mixing seeds of sunflower roasted by an oven with caramel to give the objective ice cream of sunflower.

JPH11137180A: Salmon Ice Cream

PROBLEM TO BE SOLVED: To obtain salmon-contg. ice cream by mixing salmon in ice cream, and to provide a method for producing the above dessert, intended to offer a new commodity using salmon in the districts noted therefor and accomplished by proposing a technology to lower the freezing temperature of salmon and a second technology to remove the fishy smell inherent in salmon.

SOLUTION: This salmon-contg. ice cream is obtained by mixing salmon flesh boiled with alcohol during ice cream production process followed by chilling (freezing) the resultant mixture.

JPH06217700A: Chinese noodle seasoned with miso ice cream

PURPOSE: To provide a tasty ice cream-based Chinese noodle seasoned with miso intended to activate the relevant market as well as furnish consumers with joyfulness.

CONSTITUTION: Raw noodles are boiled with cow milk and then put into chilled cow milk and cooled. The resultant cooled noodles are boiled with a liquor comprising 80wt.% alcohol, 10wt.% miso and 10wt.% pig bone soup and infiltrated with the alcohol followed by cooling again. The resultant noodles are mixed with an ice cream base which has been separately prepared by incorporating an ice cream base with miso, followed by chilling, thus obtaining the objective ice cream-based Chinese noodles seasoned with miso.

JPH06217699A: Chinese noodle seasoned with soy ice cream

PURPOSE: To provide a tasty ice cream based Chinese noodle seasoned with soy intended to activate the relevant market as well as furnish consumers with joyfulness.

CONSTITUTION: Raw noodles are boiled with cow milk and then put into chilled cow milk and cooled. The resultant cooled noodles are boiled with a liquor comprising 80wt.% alcohol, 5wt.% of soy and 15wt.% seasoned shark fin soup and infiltrated with the alcohol followed by cooling again. The resultant noodles are mixed with an ice cream base which has been separately prepared by incorporating an ice cream base with a seasoned shark fin soup, followed by chilling, thus obtaining the objective ice cream-based Chinese noodles seasoned with soy.

JPH0998722A: Silk ice cream

PROBLEM TO BE SOLVED: To produce silk-contained ice cream perceivable by tongue and eyes that the ice cream contains silk by mixing silk, which is good for health, into ice cream and the unbaked dough of pie, and further spraying silk powder over the baked pie to lay it on the ice cream.

SOLUTION: Silk powder is added and mixed into ice cream base commercial or originally blended which has been sterilized by heating and cooled. Pie dough is also compounded with silk powder, and it is formed into a shape of a silk worm or a cocoon and baked. The pie is placed on ice cream. Silk powder is sprayed over the pie. This enables one to clearly perceive that the pie has silk and to directly taste the silk powder.

JPH08277399A: Cypress flavor for food

PURPOSE: To obtain a cypress flavor for food, having excellent deliciousness, taste and palatability and useful for the preparation of a cake, etc., by adding water to cypress wood chips, heating the chips to distill out a liquid component and removing the water from the liquid by evaporation.

CONSTITUTION: This cypress flavor is produced by adding water to cypress wood chips preferably mixed with false arborvitae wood chips, heating the chips to distill out a liquid component and removing water from the liquid by evaporation.

JPH06233655A: Beer ice cream

PURPOSE: To obtain an ice cream of beer taste having a mellowness and pleasantness to the palate.

CONSTITUTION: The alcohol degree of beer is weakened and mixed with a fresh cream, whole powder milk and a stabilizer so as to prevent the beer from becoming a sherbet state and blended with an ice cream base to give a beer ice.

JPH06343397A: Japanese rice wine ice cream

PURPOSE: To obtain a tasty ice cream having the taste of Japanese rice wine.

CONSTITUTION: The ice cream is obtained by adding SAKE (Japanese rice wine) lees to an ice cream base composed of sugar, cow's milk, an egg, fresh cream, skim milk powder, glucose and a stabilizer and cooling the resultant mixture.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Mar 29, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Food, Inventions, Patents

Cucumber Sandwich Patent

Artist Alex Stenzel not only invented a cucumber sandwich, but in 2006 he managed to obtain a patent for it. It's a design patent, but a patent nonetheless.His idea was to hollow out a cucumber and stuff it with ingredients. He then used one end of the cucumber to plug up the other stuffed side. He called this a 'gorilla sandwich'.

The site dailytitan.com offers some details about how Stenzel came up with his idea:

The name 'Gorilla Sandwich,' according to Stenzel, was chosen after researching gorillas and discovering their diet consists of many greens that are high in protein.

"I'm very much into health," Stenzel said. "I've always been playing around with different types of herbs and different kinds of vegetables."

Stenzel, who is originally from an industrial area in Germany, came across this idea when confronted with a choice: eat his salad at home or store it inside a hollowed-out cucumber to make it portable enough to take to the beach with him. For Stenzel, who is a surfing enthusiast, the answer was obvious, and he was soon off to the beach to 'kiss the waves,' as he calls it, with his new edible invention. Stenzel also has had a world ranking for three different sports: tennis, mountain biking and the Iron Man World Championships in Hawaii in 1986.

"To reach the highest performance level possible, I experimented with different healthy diets," he said.

Stenzel has posted a series of videos on YouTube that provide complete instructions on how you can make your own gorilla sandwich.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Mar 25, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Food, Vegetables, Inventions, Patents

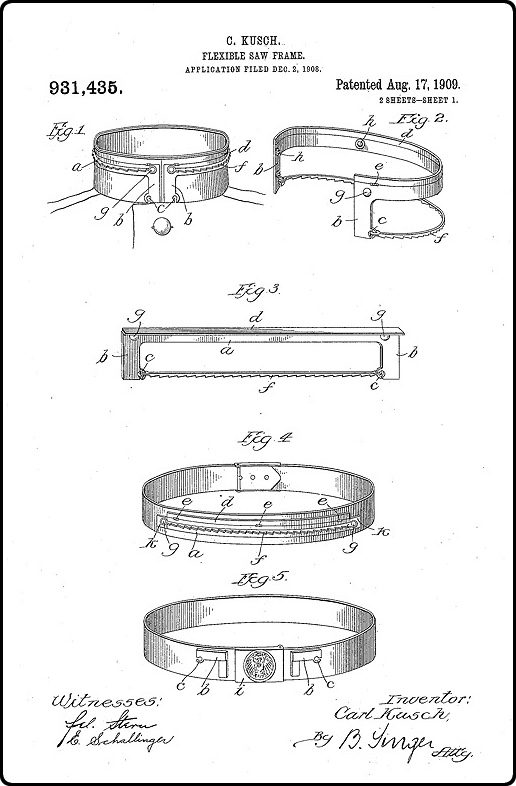

The collar saw of Carl Kusch

Carl Kusch of Germany invented a way that a person would never be without a saw when they needed one, because the saw could be worn around their neck at all times. From his 1909 patent:The invention consists in a flexible saw frame convertible at any time by suitable means into a rigid frame and which is so constructed that the saw blade can be put into the frame in the known manner, when the saw is used as a tool, or be fixed to the flat side of the frame when the frame is used as a guard. In the latter case the frame of the saw protects the dress or the body from contact with the saw blade.

Kusch evidently had high hopes for his invention, because he obtained patents for it in the United States, Great Britain, France, Switzerland, Austria, and Germany. Although in his patent he never explained who he thought was going to buy the thing. The military, I'm guessing, because it seems designed to be part of a German soldier's uniform. Although as far as I know, no army ever outfitted its soldiers with this thing.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Mar 22, 2020 -

Comments (7)

Category: Fashion, Inventions, Patents, Military, 1900s

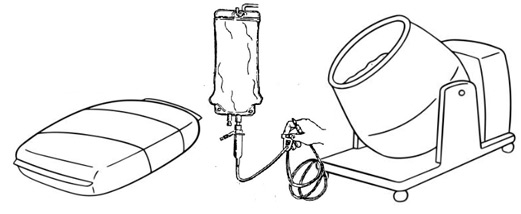

The use of blood to make concrete

In 1980, Charles Laleman of France received a US patent (No. 4,203,674) for a technique for making concrete by mixing together cement with blood. His patent described a variety of different recipes one could use to create this blood concrete. For instance:

A light colloidal concrete is prepared by using:

a commercially available cement (cement CPA 400), a silico-calcareous sand graded no higher than 0.8 mm (the cement/sand mass ratio being equal to 1), whole blood powder of animal origin, a colloid, and mixing water in variable proportions.

The various constituents are mixed by means of a mixer working between 100 and 600 r.p.m.

The advantage of using blood, Laleman argued, was that the oxygen in it produced a lighter concrete.

Curiously, Laleman acknowledged that the idea of using blood to make concrete wasn't in any way new. He cited a variety of earlier patents, such as US patent 1,020,325 from 1912 which described mixing blood into concrete. And, in fact, the technique of using blood to make concrete was even practiced by the ancient Romans.

What made Laleman's technique unique (and therefore patentable) was apparently that he used it specifically to lighten the concrete, rather than to color it or to make it more porous. That seems like a rather fine distinction to me, but it was enough to earn him a patent.

Laleman's list of earlier patents includes another oddity. He refers to US Patent No. 3,536,507 (from 1970) which describes making concrete by combining cement with "an admixture which is derived from the fermentation liquor resulting from the aerobic fermentation of liquid carbohydrates, e.g., molasses from beet or cane sugar, corn, wheat or wood pulp." That sounds like a fancy way of saying they were mixing cement with beer.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Mar 15, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Engineering and Construction, Inventions, Patents, 1980s, Blood

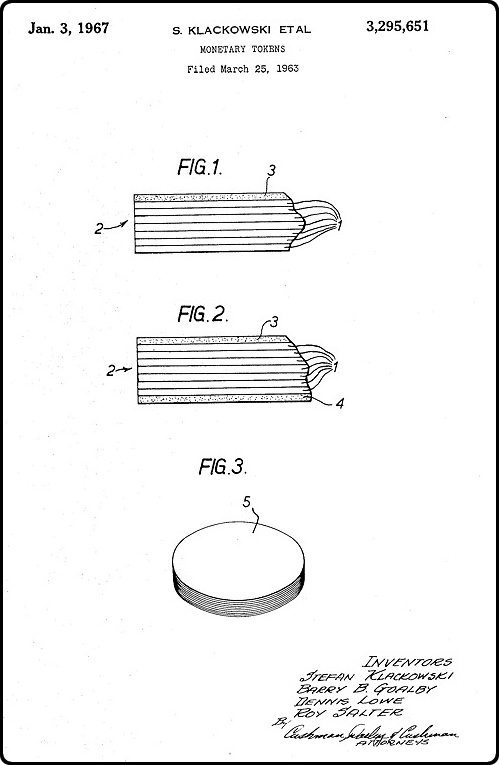

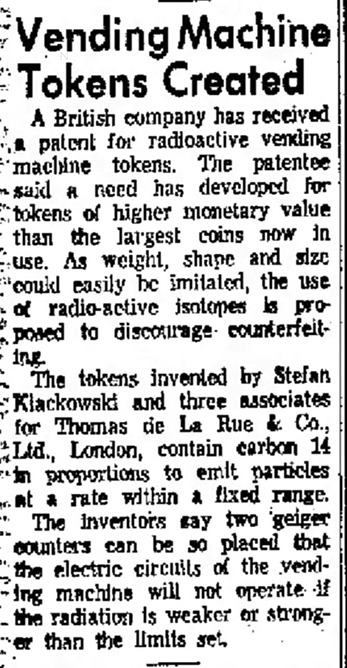

Radioactive Vending Machine Tokens

Sometimes vendors would like to sell relatively high-value items in vending machines. That is, merchandise worth more than a candy bar. Nowadays that's not a problem because there's technology that can scan paper currency or read credit cards, making larger transactions possible.But back in the 1960s, vending machines relied on coins for payment, so selling high-value merchandise wasn't practical. Especially since the machines could only measure weight, shape, and size to determine if the coins were real — and these characteristics are easy to fake with low-value blanks.

The British printing company Thomas de la Rue devised a solution: radioactive vending machine tokens.

Its researchers realized it would be possible to create tokens made out of layers of radioactive materials such as uranium and carbon14. These tokens would emit unique radioactive signatures that could be measured by Geiger counters inside a vending machine. Such tokens wouldn't be easy to forge. The company patented this idea in 1967.

I'm not aware that any vending machines accepting radioactive tokens were ever put into to use.

I imagine they would have suffered from the same problem that plagued other efforts to put radiation to practical, everyday use — such as the radioactive golf balls we posted about a few months ago (the radiation made it possible to find the balls if lost). The radiation from one token (or golf ball) wasn't a health hazard, but if a bunch of them were stored together, then the radiation did become a problem.

Nashua Telegraph - Jan 11, 1967

Posted By: Alex - Sun Mar 08, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1960s

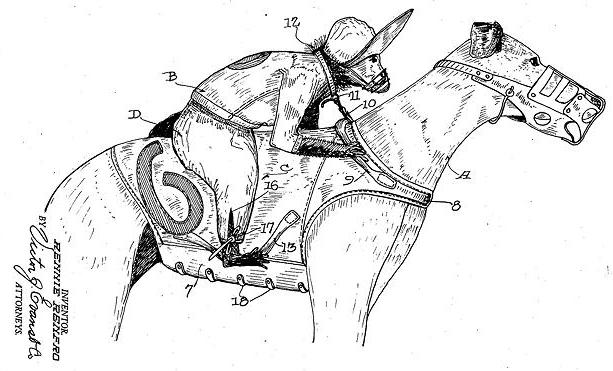

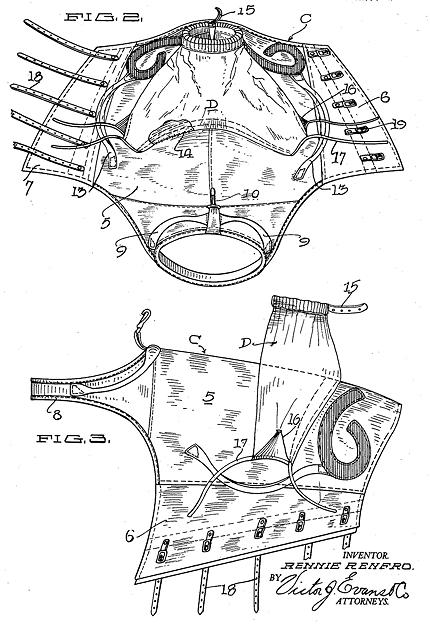

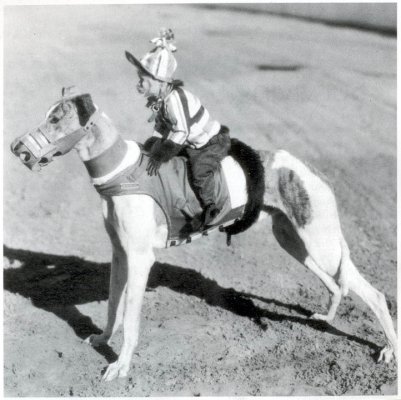

Monkey jockeys race greyhounds

In the early 1930s, a new feature was introduced at some greyhound races: monkey jockeys. Apparently the crowds loved the idea. The problem was, the monkeys had trouble staying on the backs of the greyhounds. Animal trainer Rennie Renfro came up with a solution — a special harness that would tie the monkey onto the back of the dog. Renfro patented his invention in 1933.It probably made him some money, because I can find descriptions of races with monkey jockeys for decades afterwards.

Rennie Renfro (left) and his wife

St. Louis Post Dispatch - July 2, 1933

image source: Greyhound Articles Online

Posted By: Alex - Sun Mar 01, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Sports, 1930s

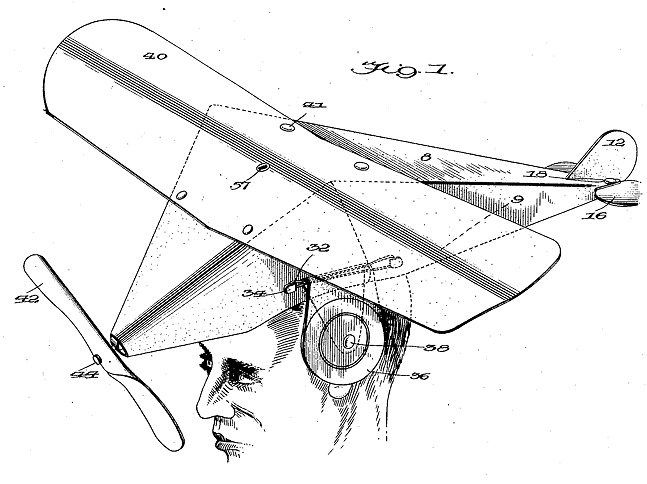

Airplane Hat

Created by Gilbert Myers of Boise, Idaho. He was evidently worried that someone might steal his idea because, in 1929, he patented it. From the patent:Use of a number of novelty hats constructed as herein disclosed has demonstrated that the hat enjoys the favor of adults as well as children and may be applied to heads of various sizes in a highly convenient and expeditious manner and will remain firmly in place, all without exerting an objectionable pressure on the head.

The picture below shows the airplane hat being worn. (The accompanying article identified it as Myers's hat).

Minneapolis Star Tribune - Feb 2, 1930

These other photos, of actress Alice White, I'm not so sure about. It looks a lot like his hat. If it isn't, someone ignored his patent.

source: Flickr

Battle Creek Enquirer - Jan 14, 1930

Posted By: Alex - Sun Feb 23, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Patents, Air Travel and Airlines, Headgear, 1920s

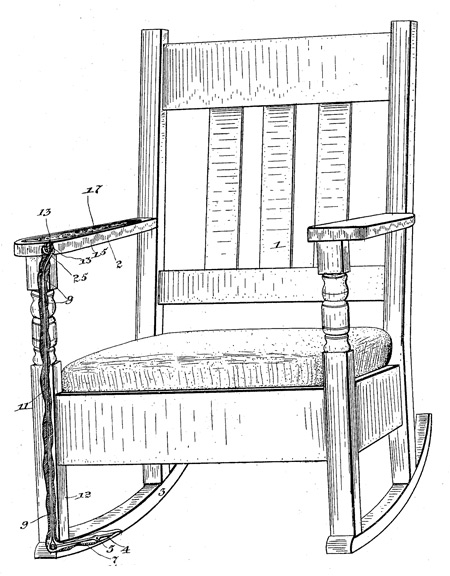

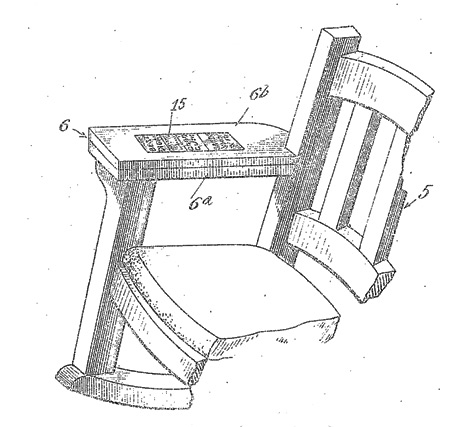

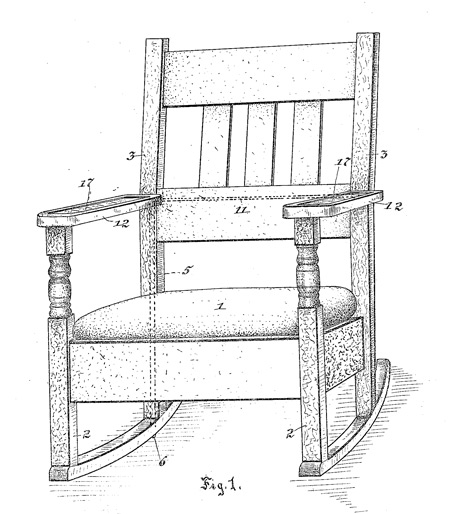

Advertising Chairs

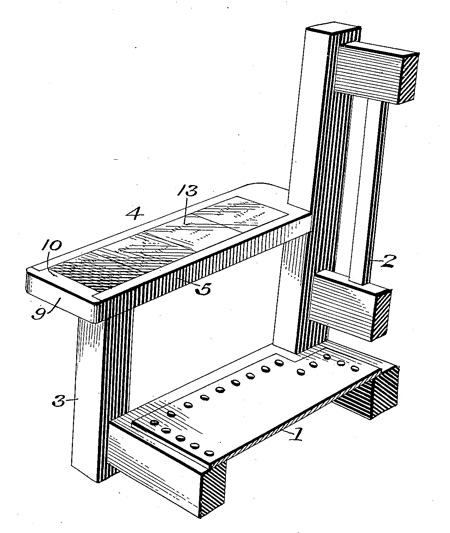

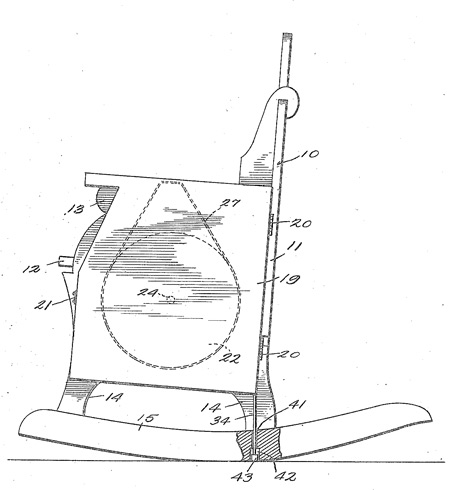

Back in 2018, Paul posted about an "advertising chair" patented in 1910. As a person rocked in it, advertisements scrolled in the armrests.

Patent No. 958,793 (1910)

I recently discovered that this invention wasn't a one-off. In the early twentieth century, inventors were actively competing to perfect advertising chairs and inflict them on the public. I was able to find four other advertising chair patents (and there's probably even more than this). To my untrained eye, they all look very similar, but evidently they were different enough to each get their own patent.

Patent No. 934,856 (1909)

Patent No. 993,397 (1911)

Patent No. 1,094,154 (1914)

Patent No. 1,441,911 (1923)

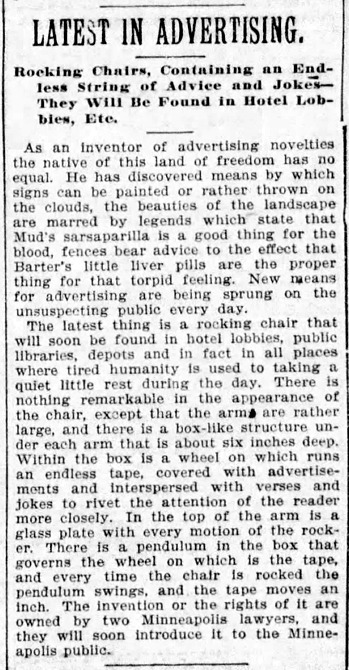

A newspaper search brought up an 1895 article that described advertising chairs as the "latest in advertising." It also explained that the concept was to put these chairs in various places where there were captive audiences, such as "hotel lobbies, public libraries, depots and in fact in all places where tired humanity is used to taking a quiet little rest during the day."

Minneapolis Star Tribune (Dec 8, 1895)

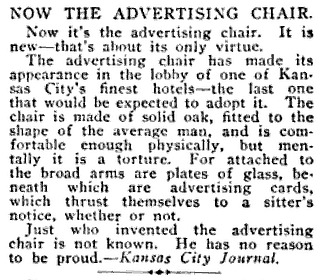

But although entrepreneurs may have been keen to build advertising chairs, the public was evidently far less enthusiastic about them. An editorial in the Kansas City Journal (reprinted in Printer's Ink magazine - Jan 2, 1901) described an advertising chair as "comfortable enough physically, but mentally it is a torture... Just who invented the advertising chair is not known. He has no reason to be proud."

There must have been a number of these advertising chairs in existence, but I'm unable to find any surviving examples of them. Searching eBay, for instance, only pulls up chairs with advertisements printed on them.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Feb 18, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Furniture, Inventions, Patents, Advertising

Shoe Gongs

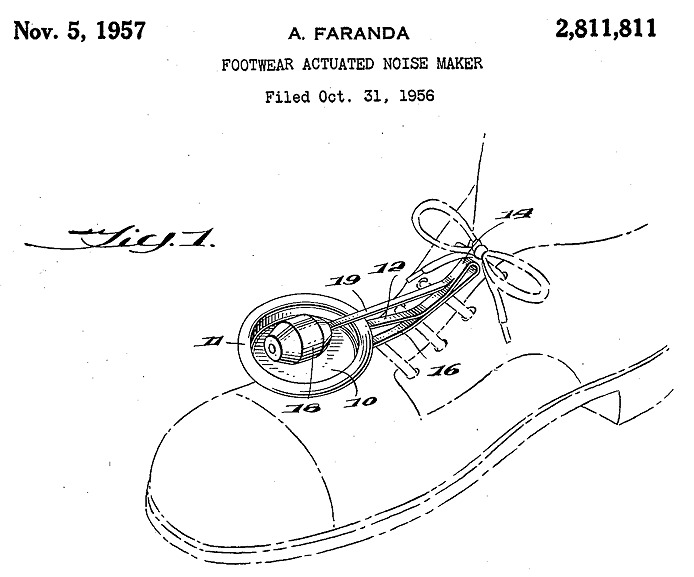

Anthony Faranda of Yonkers, NY worried that children didn't like wearing rubber-soled shoes because they made no noise when walking on a pavement. So, he invented a shoe gong. Or, as he called it, a "footwear actuated noise maker." He patented it in 1957.It was a disc and clapper that could be worn over shoes. He explained: "The arrangement is such that upon normal walking steps or running strides the clapper is activated to make noise and thereby promote the interest of children in wearing shoes with soles that do not make an audible sound in engaging firm or rigid surfaces."

Maybe kids would have liked these, but not, I imagine, their parents.

He assigned the patent to the NY advertising agency McCann-Erickson. It's unclear what plans they might have had for these things.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Feb 16, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Shoes, 1950s

Throwing Animals for Taking Death Leaps

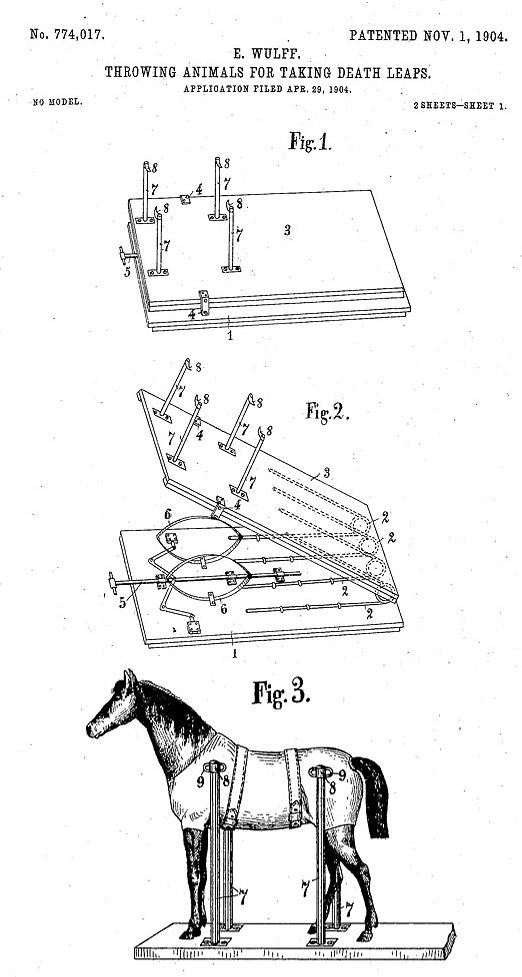

Circus proprietor Edward Wulff patented a curious device in 1904. It was an apparatus that catapulted animals upwards. It had the rather alarming title, "Throwing Animals For Taking Death Leaps" (Patent No. 774,017). Wulff claimed it could throw "horses, elephants, monkeys, &c.." The patent illustration shows a horse, so these were evidently the primary animal being thrown.

The device was relatively straight-forward. The animals were placed in a harness that held them on top of a spring-powered platform. The release of the springs then flung the animals upwards. Wulff emphasized that his apparatus was designed, via the harness, to place the projecting force on the full body of the animal, rather than just their legs. He seemed to feel that this was a safer, more humane method of throwing animals.

Wulff explained that this device was designed to be used as part of a circus stunt known as "a death leap or so-called 'salto-mortale.'" But he didn't offer any further explanation about the nature of the stunt or how far the animals were flung. And I couldn't locate any descriptions of this stunt in other sources. All the references to a 'death leap' stunt that I came across involved human trapeze artists, not animals. So I was about to conclude that the stunt would have to remain a mystery until I got the idea to check if Wulff had filed the patent in any other countries. Sure enough, there was a British version of the patent, and while its text was almost identical, it had a different title that explained the nature of the stunt:

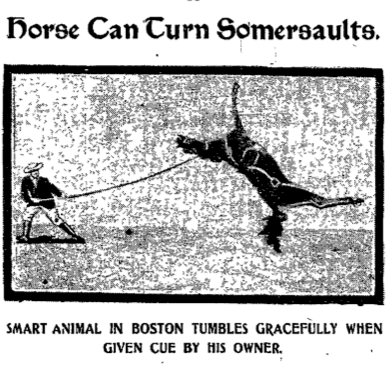

So Wullf's apparatus was evidently designed to somersault animals. Not simply to catapult them upwards. This made me recall something I posted here on WU back in 2012. It was a brief item that appeared on the front page of the Washington Post's 'Miscellany Section' on April 21, 1907, titled 'Horse Can Turn Somersaults.' At the time, this random reference to a somersaulting horse totally baffled me. I even suspected it was a hoax. But now it makes sense. It must have been a circus stunt. Perhaps it even made use of Wulff's invention. I can't find any evidence that Wulff's circus was in Boston in April 1907, but it was in New York in December of that year.

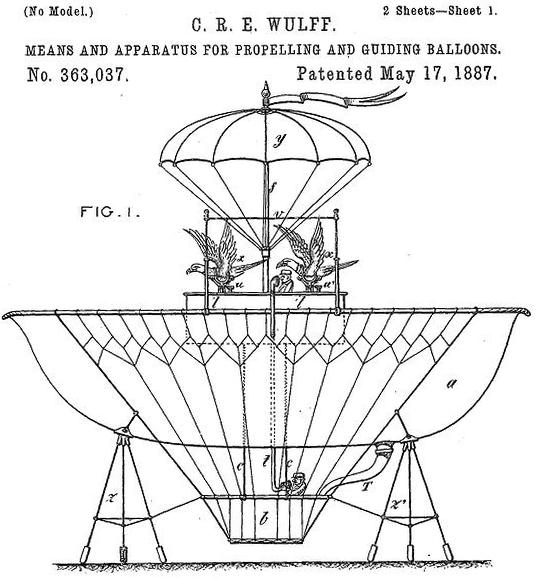

Wulff, it turns out, was the author of another odd patent, granted to him in 1887. The patent was titled, "Means and apparatus for propelling and guiding balloons." He intended to use birds such as "eagles, vultures, condors, &c" to guide balloons. The birds would be attached to the balloon by a harness, and an aeronaut would then force them to fly in the desired direction, thereby propelling the balloon.

This patent has received quite a bit of attention, because there's a lot of interest in the history of early attempts at flying machines. Knowing that Wulff was a circus proprietor, I wonder if he intended his eagle-guided balloon to be used as part of a circus act, rather than as a practical flying machine.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Feb 09, 2020 -

Comments (6)

Category: Animals, Inventions, Patents, ShowBiz, 1900s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |