Poetry

Ursonate

Sound poetry by German poet Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948). From wikipedia:I made it through about a minute before bailing. But in the poem's favor, the Nazis didn't like either it or Schwitters, classifying his art as "degenerate."

Wikipedia also relates the following anecdote. Following the outbreak of WWII, Schwitters fled to England where, as an enemy alien, he was placed in an interment camp: "Schwitters was well-liked in the camp, and was a welcome distraction from the internment they were suffering. Fellow internees would later recall fondly his curious habits of sleeping under his bed and barking like a dog.'

A version of the poem animated by Lisa Placet is easier to take in:

More info: Dangerous Minds

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jul 16, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Poetry

Patience Worth

Pearl Lenore Curran wrote four novels and many poems, but claimed that they had all been dictated to her by a woman named Patience Worth who had lived over two hundred years earlier. So, A body of work that was literally ghost-written.Info from Superstition and the Press (1983) by Curtis MacDougall:

Note: the Patience Worth poems were included in Braithwaite's 1918 anthology, not the 1917 one.

More info: Wikipedia, Smithsonian magazine

You can also find the Patience Worth novels on archive.org.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jun 12, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Literature, Books, Poetry, Paranormal

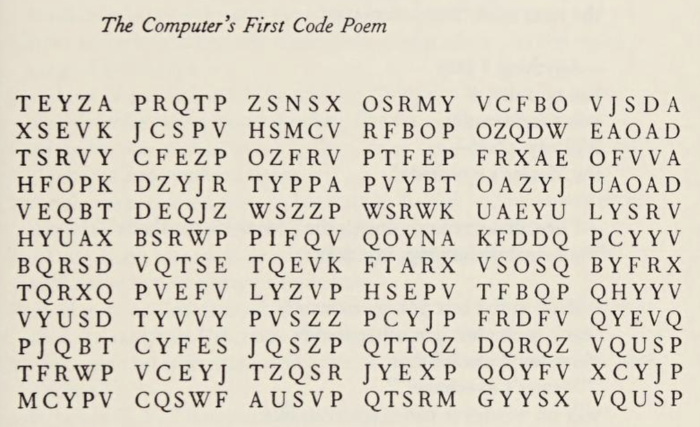

The Computer’s First Code Poem

Scottish poet Edwin Morgan included "The Computer's First Code Poem" in his 1973 collection From Glasgow to Saturn.

Despite what the title may imply, Morgan didn't actually program a computer to produce the poem. (Nor did he have the Loch Ness Monster pen "The Loch Ness Monster's Song" in the same collection.) However, the poem really is in code, as he later explained:

I didn't bother to try to crack the code. Instead, I found someone online (Nick Pelling) who had done it. Apparently it's a simple letter-substitution code, which produces:

dirty whist fight numbs black rebec

pinto hurls bdunt spurs under butte

fubsy clown posse stomp below xebec

tramp crawl kills kinky xerox joint

foxed minks squal above yucca shoot

manic tapir party upend tibia mound

panda strut jolts first pumas afoot

toxic potto still shows uncut aorta

swamp houri wails appal canal taxis

punks throw plain words about dhows

ghost haiku exits aping zooid taxis

That's not much more intelligible than the original poem. Pelling speculates that we can't rule out the possibility of a second hidden message within the first message.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Apr 28, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Codes, Cryptography, Puzzles, Riddles, Rebuses and Other Language Alterations, Computers, Poetry

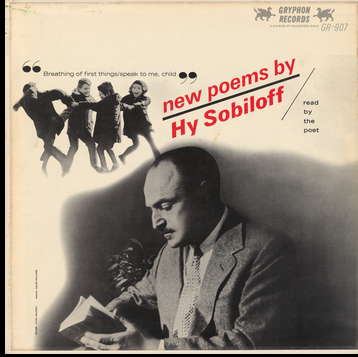

The Poetry of Hy Sobiloff

Something tells me Sobiloff should have stuck to his other careers.From his encyclopedia entry:

Sobiloff, whose poetry was respected by many of his better-known contemporaries for its fresh, honest, unpretentious qualities, was also widely known as a filmmaker, industrialist, and philanthropist... While praising his work, both Aiken and Tate come close to representing the poet as a primitive, particularly by their use of words such as "folk" or "unaware..." Less positive were Kimon Friar's judgments of the collection, as presented in Saturday Review: "Sobiloff's poems are monolithic, his lines lack cadence, there is no melodic progression within a single stanza or between stanzas. Instead, we have staccato and precise descriptions of objects, but with little of the poetic realism of a William Carlos Williams or of the subtlety of Wallace Stevens."

Posted By: Paul - Thu Mar 21, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Amateurs and Fans, Vinyl Albums and Other Media Recordings, Poetry, 1960s

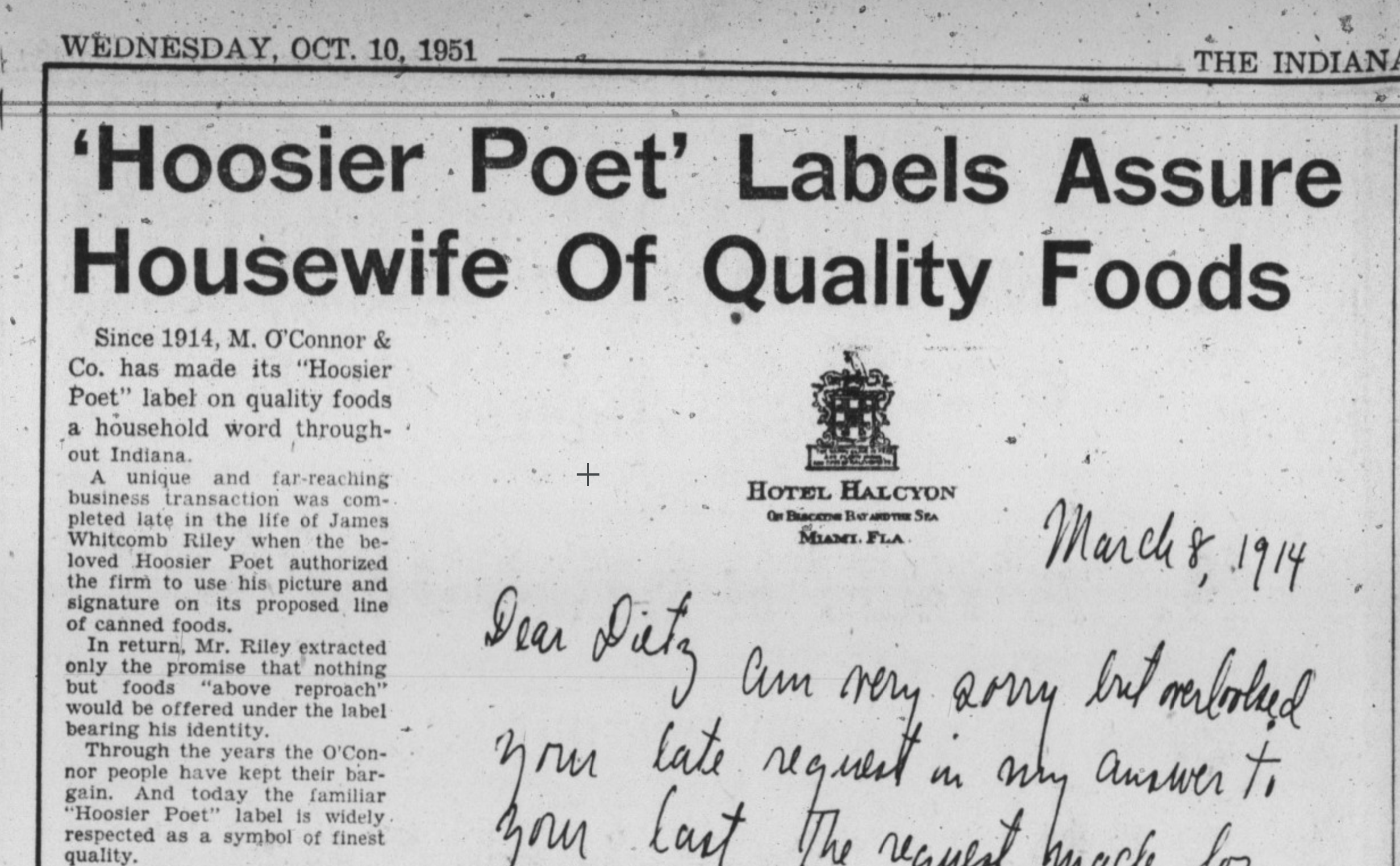

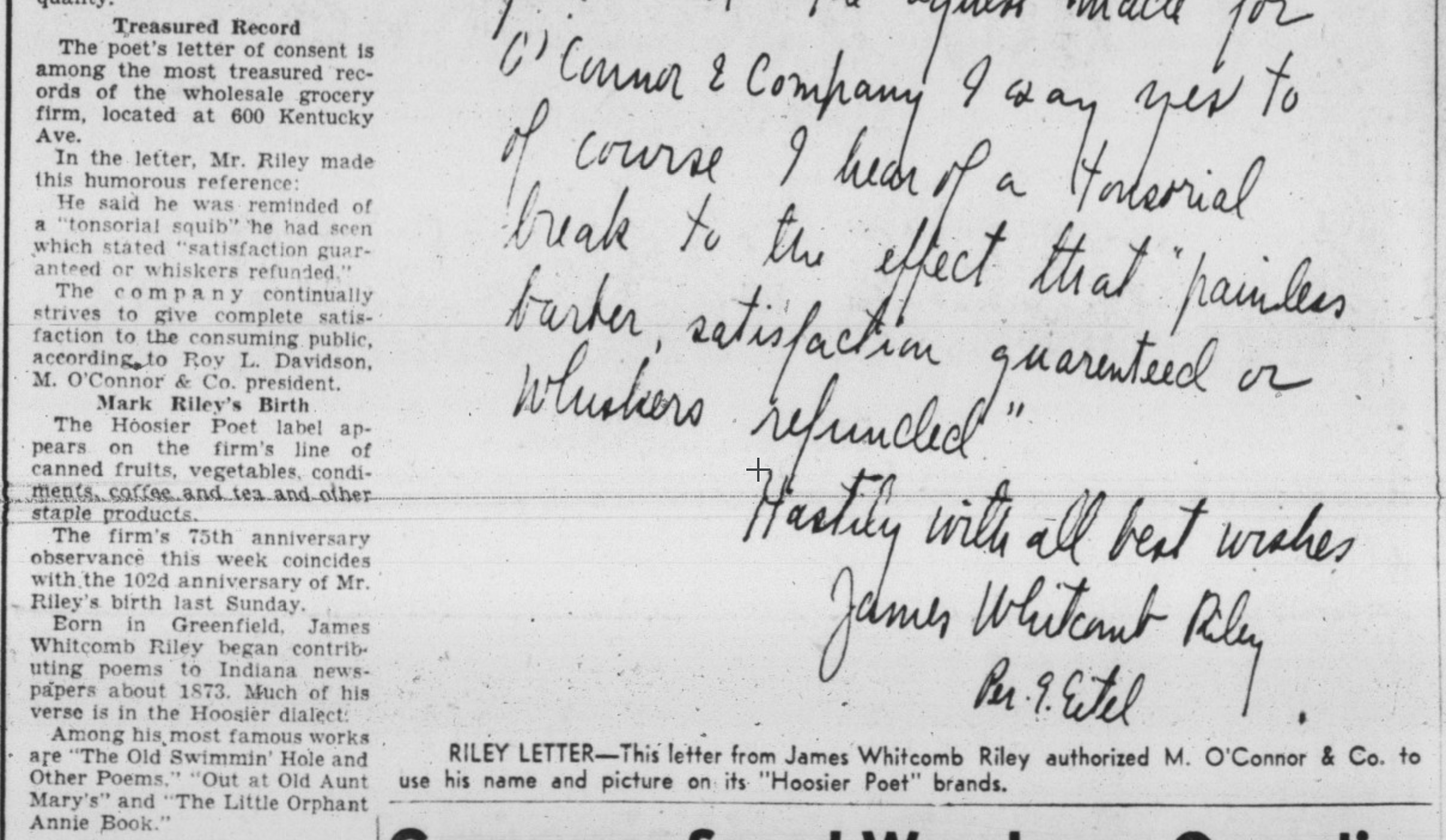

Hoosier Poet Canned Goods

Very few--if any other--poets have a line of canned goods named after them, as did James Whitcomb Riley.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Jul 14, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Food, Poetry, Nineteenth Century, Twentieth Century

Midwatch In Verse

A new book explores the obscure poetic tradition of sailors in the U.S. Navy writing the first deck log of the new year in verse. As explained by the NW Arkansas Democrat-Gazette:The records, quasi-legal documents, were a requirement of each ship to note various bits of technical information -- ship speed and direction, even the number of propeller rotations and other things that would only be useful or make sense if you were in the Navy.

But one time of year, sailors were allowed to deviate from the benign record keeping and exhibit creativity with brief storytelling. During the first watch of the New Year, from midnight to 4 a.m., the Officer of the Deck could record in verse.

No one is sure when, or why this tradition began. The earliest known example (reproduced below) dates back to 1926, but the tradition was apparently already well established by then.

More info: midwatch-in-verse.com

| I stand on the deck at midnight As the clocks are striking the hour And I’ll keep the watch until morning To the best of my humble power. We are anchored in Pedro harbor Tho there isn’t much of a lee And why they call it a harbor Is something I never could see But our hook is in hole A seven And our center anchor chain Has forty-five in the hawse pipe And a very gentle strain. When we anchored our trusty leadsman Made a very careful cast Finding eight and a half good fathoms As the bugler blew the blast. And down below in the fire rooms Which the black gang ought to man The steam is blowing bubbles In number seven can. All the battleship divisions Swing nearby on the blue Except the West Virginia And the Mississippi too. The Senior Officer Present Floats peacefully in his sleep On the good ship California The guardian of the deep. At one fifteen Roskelly A pill rolling pharmacist’s mate Returned from his leave on schedule He’s lucky he wasn’t late. That’s all the dope this morning Except, just between us two If the Captain ever sees this log My gawd what will he do? E.V. Dockweiler, Ensign, U. S. Navy |

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jan 20, 2023 -

Comments (4)

Category: Military, Books, Poetry

Jazz Poetry

The Wikipedia entry, followed by some examples from the Boston Post, 09 Jan 1921, Sun Page 53.

Posted By: Paul - Sat May 28, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Fads, Music, Poetry, Bohemians, Beatniks, Hippies and Slackers, 1920s

Dyr bul shchyl

The Russian artist Alexei Kruchenykh invented the Zaum language in 1913. He described it as "a language which does not have any definite meaning." From what I can gather, it was gibberish sounds strung together.Dyr bul shchyl, also written by Kruchenykh, was the first (but not last) poem written in Zaum.

ubeshshchur

skum

vy so bu

r l ez

You can hear Kruchenykh reading the poem aloud in the first clip. There's a more modern interpretation of it below.

Knowing Russian, or any other language, won't help you understand the poem. But according to Russian language expert Lucas Stratton, "critics have interpreted Dyr bul shchyl as an arrangement of sounds associated with a coming storm."

Posted By: Alex - Sun Nov 29, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Languages, Poetry, 1910s, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

The Poet Laureate of Dentistry

Note: after preparing this post, I realized that Paul had posted about the same thing two years ago. So consider this a repost.Soylman Brown (1790-1876) was a Connecticut dentist who achieved prominence in his profession for a number of reasons. According to Wikipedia, he founded the first dental school, the first national dental society, and the first US dental journal. Plus, he became known as the Poet Laureate of Dentistry on account of his fifty-four page poem titled Dentologia - A Poem on Diseases of the Teeth, and Their Proper Remedies. It was published in 1840.

If you've got some time to kill, you can read the entire poem at the Internet Archive. Otherwise, I've sampled a brief part of it below, which should be enough to give you its general tone.

For oft, obstructed nature, laboring there,

Demands assistance of experienced art,

And seeks from science her appointed part.

Perhaps ere yet the infant tongue can tell

The seat of anguish that it knows too well,

Some struggling tooth, just bursting into day,

Obtuse and vigorous, urges on its way,

While inflammation, pain, and bitter cries,

And flooding tears, in sad succession rise.

The lancet, then, alone can give relief,

And mitigate the helpless sufferer's grief;

But no unpractised hand should guide the steel

Whose polished point must carry wo or weal:—

With nicest skill the dentist's hand can touch,

And neither wound too little nor too much.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Nov 22, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Poetry, Nineteenth Century, Teeth

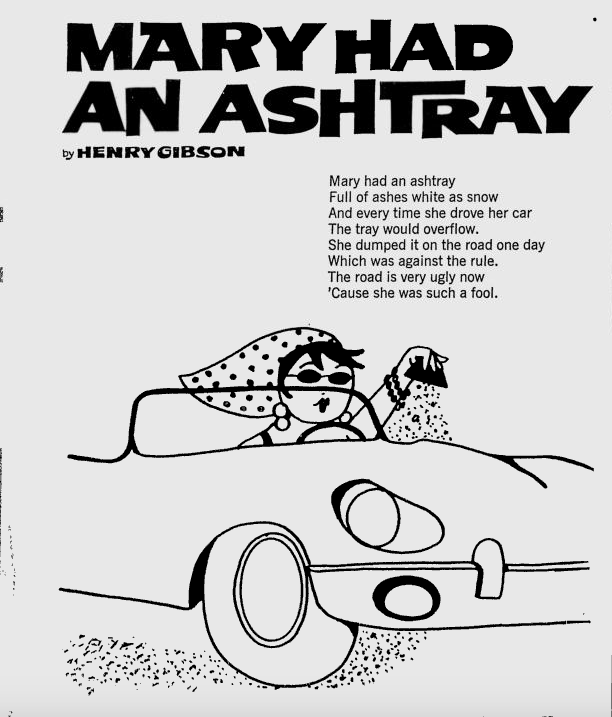

Henry Gibson Anti-Littering Ads

Anyone of a certain age recalls Henry Gibson and his "naive" poems on LAUGH-IN. Apparently, some ad agency thought he'd be perfect for their anti-littering campaign.

Source.

And they were even collected in a book, by the Glass Container Manufacturers Institute.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jul 25, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: PSA’s, Television, Poetry, 1960s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |